12

Risk Management, Business Continuity, and Emergency Management

KEY TERMS

• risk

• bond

• Terrorism Risk Insurance Act of 2002

• NFPA 1600 Standard on Disaster/Emergency Management and Business Continuity Programs

• organizational behavior theory

• risk perception and communication theory

• social constructionist theory

• all-hazards preparedness concept

• generic emergency management

• specialized emergency management

• Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)

• response

• recovery

• National Response Plan (NRP)

• National Incident Management System (NIMS)

After studying this chapter, the reader will be able to:

1. Define risk management and explain its purpose.

2. Describe the role of the risk manager.

3. Explain the risk management process, risk modeling, risk management tools, and enterprise risk management.

4. List and explain at least eight types of insurance.

5. Elaborate on the insurance claims process.

6. Discuss how to establish a business continuity plan.

7. Explain the role of government in risk management, all-hazards preparedness, and emergency management.

Note: Portions of this chapter are from: Purpura, P. (2007). Terrorism and Homeland Security: An Introduction with Applications. Burlington, MA: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann.

Risk Management

As defined in Chapter 2, risk is the measurement of the frequency, probability, and severity of losses from exposure to threats or hazards (e.g., crime, fire, accident, and natural disaster). The wise businessperson is knowledgeable about all exposures. Business interruption, for example, results from crime, fire, accident, flood, tornado, and the like. Another exposure is liability. A customer might become injured on the premises after falling or be harmed in some way when using a product manufactured by a business.

The most productive way of handling unavoidable risks is to manage them as well as possible. Hence, the term risk management has evolved. Risk management makes the most efficient before-the-loss arrangement for an after-the-loss continuation of a business. Insurance is a major risk management tool. Leimberg et al. (2002: 6), from the insurance industry, define risk management as follows: “A preloss exercise that reflects an organization’s postloss goals; a process to recognize and manage faulty and potentially dangerous operations, trends, and policies that could lead to loss and to minimize losses that do occur.”

Risk management is important to not only businesses, but also our whole society. It is applicable to government, institutions, all types of organizations, the family, and individuals. The purpose of risk management is to protect people and assets.

Risk management and loss prevention are naturally intertwined. Loss prevention is another tool for risk managers to make their job easier. Insurance is made more affordable through loss prevention methods. Additional risk management tools are described in subsequent pages.

Both loss prevention and risk management originated in the insurance industry. Fire insurance companies, soon after the Civil War, formed the National Board of Fire Underwriters, which was instrumental in reducing loss of life and property through prevention measures. Today, loss prevention has spread throughout the insurance industry and into the business community. Risk management is also an old practice. The modern history of risk management is said by many insurance experts to have begun in 1931, with the establishment of the insurance section of the American Management Association. The insurance section holds conferences and workshops for those in the insurance and risk management field.

Risk management theory draws on probability and statistics, mathematics, engineering, economics, business, and the social sciences, among other disciplines. The study of risk has expanded to include the understanding of the psychological, cultural, and social context of risk. The expanding nature of the study of risk is illustrated by the two theories that follow (Borodzicz, 2005: 14–47).

• Risk perception theory focuses on how humans learn from their environment and react to it. Psychologists apply a cognitive research approach to understand how humans gain knowledge through perception and reasoning. For instance, risk can be researched by isolating a variable and simulating it in a laboratory with a group of subjects in an experiment involving risk decision making (e.g., gambling). The psychometric approach is another method of researching risk; it involves a survey to measure individual views of risks. Research on risk perception shows that people find unusual risks to be more terrifying than familiar ones and, interestingly, the familiar risks claim the most lives; voluntary risk (e.g., smoking) is preferred over imposed risk (e.g., a hazardous industry moving near one’s home); and people have limited trust in official data.

• Risk communication theory concerns itself with communication perceptions of experts and lay citizens. Although experts work to simplify information for lay citizens, communication of simplified information and behavior change may not be successful. Research on this topic focuses on lay citizen perceptions of risk within the context of psychological, social, cultural, and political factors. Risk communication theory is important because it holds answers for educating and preparing citizens for emergencies.

The Role of the Risk Manager

Traditionally, businesses purchased insurance through outside insurance brokers. Generally, a broker brings together a buyer and a seller. Insurance brokers are especially helpful when a company seeking insurance has no proprietary risk manager to analyze risks and plan insurance coverage. Not all businesses can afford the services of a broker or a proprietary risk manager; however, risk management tools are applicable to all entities.

The risk manager’s job varies with the company served. He or she may be responsible for insurance only; or for security, safety, and insurance; or for loss prevention, insurance, investments, and business continuity. One important consideration in the implementation of a risk management (or loss prevention) program is that the program must be explained in financial terms to top executives. Is the program cost effective? What is the return on investment? Financial benefits and financial protection are primary expectations of top executives that the risk manager must consider during decision making. Leimberg et al. (2002: 4) write

It is extremely difficult to measure tangible benefits against a nonevent (i.e., the catastrophic loss did not occur due to our highly effective risk management program). Yet this is the challenge facing all risk managers. Ultimately, the metrics that senior management uses to gauge success—for example, earnings growth and return on invested capital—must also serve as the yardsticks used to measure the effectiveness of risk management.

Research in England of the activities of risk managers in 30 different organizations showed five major factors influenced risk managers’ roles. Top management had a major influence on the risk manager in the form of direct instruction on primary tasks. External influences included recommendations from outside groups to increase attention to risk management within businesses and requirements for risk reporting. The nature of the business, corporate developments (e.g., expansion and exposures), and characteristics of the risk management department (e.g., resources available) also influenced the role of the risk manager (Ward, 2001: 7–25).

Among the many activities of the traditional risk manager are to develop specifications for insurance coverage wanted, meet with insurance company representatives, study various policies, and decide on the most appropriate coverage at the best possible price. Coverage may be required by law or contract, such as workers’ compensation insurance and vehicle liability insurance. Plant and equipment should be reappraised periodically to maintain adequate insurance coverage. In addition, the changing value of buildings and other assets, as well as replacement costs, must be considered in the face of depreciation and inflation (Bieber, 1987: 23–30).

It is of tremendous importance that the expectations of insurance coverage be clearly understood. The risk manager’s job could be in jeopardy if false impressions are communicated to top executives, who believe a loss is covered when it is not. Certain things may be excluded from a specific policy that might require special policies or endorsements. Insurance policies state what incidents are covered and to what degree. Incidents not covered are also stated. An understanding of stipulations concerning insurance claims, when to report a loss, to whom, and supporting documentation is essential in order not to invalidate a claim.

During this planning process, loss prevention measures are appraised in an effort to reduce insurance costs. Because premium reductions through loss prevention are a strong motivating force, risk managers may view strategies, such as security officers, as a necessary annoyance.

Deductibles are another risk management tool to cut insurance expenses. There are several forms of deductibles, but generally the policyholder pays for small losses up to a specified amount (e.g., $1,000, $10,000), while the insurance carrier pays for losses above the specified amount, less the deductible.

A major concern for the risk manager in the planning process is what amount of risk is to be assumed by the business beyond that covered by insurance and loss prevention strategies. A delicate balance should be maintained between excessive protection and excessive exposure.

Today, the risk manager’s job has become more complicated, and executives throughout corporations—from finance to human resources to corporate boards of directors—are increasingly concerned about risks. Financial failures and corporate scandals (e.g., Enron and WorldCom) illustrate the variety of risks businesses face. Regulatory laws, such as the Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) Act of 2002, reinforce the legal obligations of businesses to properly identify, assess, and manage risks. In addition, country-specific risks are becoming more important as international business operations and the global economy grow (Moody, 2006).

The Risk Management Process

As the risk management discipline developed, a need arose for a systematic approach for evaluating risk. Leimberg et al. (2002: 2–3) describe what is known as the risk management process.

Step 1, Risk Identification: Risks must be identified prior to being managed. Risks are divided into various categories. For example, first party risks involve owned assets. Damage to a company truck is a first party risk. Third party risks pertain to liability resulting from business operations. If a company truck is involved in a traffic accident, the company may be liable for property damage and injury to others not connected to the company. Risk identification is challenging because many threats and hazards face organizations, as listed in Chapter 2.

Step 2, Quantitative Analysis: Risk quantification applies probability, statistics, tools, and software to anticipate the maximum and expected financial loss from each identified risk. If a fire destroys a building costing $10 million to replace, the maximum loss is $10 million. However, loss prevention methods (e.g., fire-resistive construction and a sprinkler system) can reduce the loss significantly. Risk quantification for physical assets is usually easier than for public liability and worker safety.

Step 3, Evaluate Treatment Options: This step uses identified risks and quantitative analysis as a foundation to prepare measures to reduce exposure. Two methods included in this step are risk financing and risk control. Risk financing is very broad and can be categorized as “on-balance sheet” and “off-balance sheet.” The former includes insurance policy deductibles and self-insured loss exposures; essentially, a business absorbs losses. The latter includes insurance policies and contractual transfers of risk. Transferring risks “off-balance sheet” is not free, and costs can increase. For instance, if insured losses increase in frequency, insurance premiums and deductibles are likely to rise. Risk control, also known as loss prevention, involves precautions (e.g., security and safety methods) to reduce risk.

Step 4, Implementation: Once the treatment options are studied and planned, the next step is to put the selected options into practice.

Step 5, Monitoring and Adjusting: The risk management process concludes with program oversight, analysis, and modifications.

Risk Modeling

The process of selecting which exposures deserve increased attention is difficult. Although no person or technology can predict the future, methodologies are available to help estimate risk, while serving as a foundation for prioritizing and planning. Risk modeling offers various methodologies to estimate risk; however, it is not a “crystal ball.” The Rand Corporation, for example, developed the Delphi approach, during World War II. It consists of sending a structured questionnaire to a group of experts and then conducting a statistical analysis to generate probabilistic forecasts. To enhance the process, the experts may play the role of an adversary making decisions. Another type of risk modeling is game theory. In reference to the problem of terrorism, Starner (2003: 32) states: “Game theory suggests that the likelihood—and targets—of a future terrorist attack can be modeled by understanding the operational and behavioral characteristics of the terrorist organization.” It involves the concept that adversaries are rational and make choices based on their information and rules. Game theory is a method to get inside the minds of terrorists. The key is to know adversaries and their rules to anticipate their actions.

Modeling helps insurance companies understand risks and set premiums. Since the 9/11 attacks, for example, insurers have been asking specific questions about the number of employees at individual buildings at specific geographic locations so they can compute the risk they are accepting. For instance, if 3,000 employees are at one location, it represents a $3 billion workers’ compensation exposure in a state that puts a $1 million price tag on a life (Stoneman, 2003: 18).

Risk Management Tools

Within the risk management process, and before a final decision is made on risk management measures, the practitioner should consider the following tools for dealing with risk:

• Risk avoidance: This approach asks whether to avoid the risk. For example, the production of a proposed product is canceled because the danger inherent in the manufacturing process creates a risk that outweighs potential profits. Or, a bank avoids opening a branch in a country subject to political instability or terrorism.

• Risk transfer: Risk can be transferred to insurance. The risk manager works with an insurance company to tailor a coverage program for the risk. This approach should not be used in lieu of loss prevention measures but rather to support them. Insurance should be last in a series of defenses. Another method of transferring risk is to lease equipment rather than own it. This would transfer the risk of obsolescence.

• Risk abatement: In abatement, a risk is decreased through a loss prevention measure. Risks are not eliminated, but the severity of loss is reduced. Sprinklers, for example, reduce losses from fire. Sand bags assist in delaying erosion (Figure 12-1).

• Risk spreading: Potential losses are reduced by spreading the risk among multiple locations. For example, a copy of vital records is stored at a remote, secure location. In another example, following the 9/11 attacks, companies have spread operations among multiple locations to facilitate business continuity and survivability.

• Risk assumption: In the assumption approach, a company makes itself liable for losses. In one path, no action is taken and no insurance is obtained. This may result because the chance for loss is minute. Another path, self-insurance, provides for periodic payments to a reserve fund in case of loss. Risk assumption may be the only choice for a company if insurance cannot be obtained. With risk assumption, prevention strategies become essential.

FIGURE 12-1 Florida hotel faces risk of beach erosion from Hurricane Irene.Courtesy: Ty Harrington/fema.

Enterprise Risk Management

A trend today in the risk management field is known as enterprise risk management (ERM). Leimberg et al. (2002: 6) define it as “a management process that identifies, defines, quantifies, compares, prioritizes, and treats all of the material risks facing an organization, whether or not it is insurable.” It refers to a comprehensive risk management program that addresses a variety of business risks. Examples are risk of profit or loss; uncertainty regarding the organization’s goals as it faces its strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats; and risk of accident, fire, crime, and disasters. When all of these risks are packaged into one program, planning is improved and overall risk can be reduced. Because risks frequently are uncorrelated (i.e., all of them causing loss in the same year), insurance costs are lower. For instance, the following risks are unlikely to occur in the same year: fire, adverse movement in a foreign currency, and homicide in the workplace (Rejda, 2001: 64–66).

Leimberg et al. (2002: 6) describe the trend of two separate and distinct forms of risk management. Event risk management focuses on traditional risks (e.g., fire) that insurance covers. Financial risk management protects the financial assets of a business from risks that insurers generally avoid. Examples are foreign currency exchange risk, credit risk, and interest rate movements. Various capital risk transfer tools are available to protect financial assets. ERM seeks to combine event and financial risk for a comprehensive approach to business risks.

Since ERM is interdisciplinary in nature, corporations are forming committees for planning. At Hallmark Cards, Inc., the enterprise risk management oversight committee consists of personnel from finance, risk management, legal, human resources, IT, and internal audit (Conley, 2000: 43–50).

Should a security and loss prevention executive or a CSO be part of an enterprise risk management committee? Why or why not?

International Perspective: Risk Management in a Multinational Business

Morris (2001: 22–30) writes about overseas business operations and the need for answers to specific questions about each country in which business will be conducted. She begins with the following questions: How is business conducted in comparison to the United States? How strong is the currency? How vulnerable is the area to natural disasters, fire, and crime? What are the potential employment practices liability issues? What is the record of accomplishment of shipments to and from the area?

Political risks are especially challenging in overseas operations. Are terrorist groups or the government hostile to foreign companies and their employees? Does the host government have a record of instability and war, seizing foreign assets, capping increases in the price of products or adding taxes to undermine foreign investments, and imposing barriers to control the movement of capital out of the country?

Eighty percent of the terrorist acts committed against U.S. interests abroad target U.S. businesses, rather than governmental or military posts. These threats include kidnapping, extortion, product contamination, workplace violence, and IT sabotage.

The concept of enterprise risk management can be especially helpful with multinational businesses because of a multitude of threats. A key challenge for the risk manager is to bring together a full range of resources and network in the United States and overseas prior to potential losses so, if a loss occurs, a speedy and aggressive response helps the business to rebound.

Options for insurance include buying it in the home country and arranging coverage for overseas operations; however, this may be illegal in some countries that require admitted insurance. Another approach is to let the firm’s management in each country make the insurance decision, but this means that the corporate headquarters has less control of risk management. A third avenue is to work with a global insurer who has subsidiaries or partner insurers in each country; this approach offers uniform coverage globally. A key question in these approaches: Is the insurer financially solvent to pay the insured following a covered loss?

Insurance

Insurance is the transfer of risk from one party (the insured) to another party (the insurer), in which the insurer is obligated to indemnify (compensate) the insured for economic loss caused from an unexpected event during a period of time for which the insured makes a premium payment to the insurer. This permits the insured to avoid holding a large amount of liquid capital (cash) in reserve to pay for huge losses; the liquid capital can be invested. The essence of insurance is the sharing of risks; insurance permits the insured to substitute a small cost (the premium) for a large loss under an arrangement whereby the fortunate many who escape loss will indirectly assist in the compensation of the unfortunate few who experience loss. For an insurance company to function properly, a large number of policyholders are required. This creates a shared risk.

The technical aspects of the insurance industry involve the skills of statisticians, economists, financial analysts, engineers, attorneys, physicians, and, of course, risk managers and loss prevention specialists, among others. Insurance companies must carefully set rates, meticulously draft contracts, establish underwriting guidelines (i.e., accepting or rejecting risks for an insurance company), and invest funds prudently.

Insurance rates are dependent on two primary variables: the frequency of claims and the cost of each claim. When insurance companies periodically review rates, the “loss experience” of the immediate past is studied.

The insurance industry is subject to two forms of control: competition among insurance companies and government regulation. Competition enables the consumer to compare rates and coverage for the best possible buy. Government regulatory authorities in each state or jurisdiction have a responsibility to the public to assure the solvency of each insurance company so policyholders will be indemnified when appropriate. Furthermore, rates should be neither excessive nor unfairly discriminatory. Problems with the state system of regulation came to light following the case of Martin Frankel, who looted $200 million from insurance companies he owned during the 1990s (Gurwitt, 2001: 18–24). Since the case affected insurers in five states, Congress asked the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) to investigate. A fall 2000 report by the GAO blamed the states for inadequate regulatory policies, procedures, practices, and investigations, and a lack of information sharing. There are calls for a federal regulatory system, but the states will fight for the revenue—$10.2 billion in insurer premium taxes and fees while spending $839 million to regulate the industry. Insurance industry executives argue that “50 monkeys are better than one gorilla.”

To check on the financial health of an insurer, contact an insurance company rating service and look for a rating of A+ or better. Examples of these firms are A.M. Best and Standard & Poor’s.

Types of Insurance

Insurance can be divided into two broad categories: government and private. Government insurance programs include Social Security, Medicare, unemployment insurance, workers’ compensation, retirement, insurance on checking and savings accounts in banks, flood insurance, and numerous other programs on the federal and state levels.

In the United States, the private insurance industry is divided into property and liability (casualty) insurance and life and health insurance. This industry employs millions in the United States, among thousands of insurance companies, while administering trillions of dollars in assets. Outside the United States, the private insurance industry is divided into life and nonlife (or general) insurance. In 2005, world insurance premium volume totaled $3.4 trillion, and the United States wrote about one-third of this volume (Insurance Information Institute, 2006).

Property and liability insurance covers fire, ocean marine, inland marine (i.e., goods shipped on land), and liability insurance, which is a broad field such as general liability (e.g., from sales of products, professional services), automobile, crime, workers’ compensation, boiler and machinery, glass, and nuclear, among other types. The property and liability field also includes multiple-line insurance (i.e., two or more perils covered under one policy) and fidelity and surety bonds.

Advisory organizations have been established in the property and liability field to offer a variety of research services to insurance companies, develop policy forms, and pool loss statistics among insurance companies to increase the accuracy of rates. Two major advisory organizations are the Insurance Services Office (ISO) and the American Association of Insurance Services (AAIS).

Because types of insurance are numerous, varied and confusing, groups such as the ISO develop insurance contracts and forms and seek standardization. This group’s effort is illustrated through the commercial package policy (CPP) that contains multiple coverage in a single policy, fewer gaps in coverage, lower premiums because individual policies are not purchased, and convenience. The CPP is used by retail stores, office buildings, manufacturers, motels, hotels, apartments, schools, churches, and many other organizations. CPP coverage commonly contains two or more coverage parts. A business may select, for example, coverage focusing on commercial property, general liability, auto, and crime (Rejda, 2001: 266–268).

Crime Insurance and Bonds

Two basic kinds of protection against crime losses are (1) fidelity and surety bonds and (2) burglary, robbery, and theft insurance. The first covers losses caused by dishonesty or incapacitation from persons entrusted with money or other property that violate this trust. The second type of protection covers theft by persons who are not in a position of trust.

Various crime coverage forms, which describe what is covered, are currently in use. These forms can be issued as a monoline policy or as part of a CPP. Malecki (2006) notes that, in 2006, there was a general “tightening” of coverage conditions of commercial crime forms. For instance, courts have strengthened the exclusion that commercial crime insurance is not intended to cover employees who committed theft or dishonesty prior to issuance of a policy.

The Surety Association of America has developed forms pertaining to employee dishonesty and loss from forgery. Examples include Form A, Employee Dishonesty; Form B, Forgery or Alteration; and Forms O and P, Public Employee Dishonesty. The coverage of Form A, a bond, includes embezzlement of funds by a company’s treasurer or stealing by a cashier.

What are the differences between insurance and a bond? A bond is a legal instrument whereby one party (the surety) agrees to indemnify another party (the obligee) if the obligee incurs a loss from the person bonded (the principal or obligor). Although a bond may seem like insurance, there are differences between them. Generally, a bonding contract involves three parties, whereas an insurance contract involves two. With a bond, the surety has the legal right to attempt collection from the principal after indemnifying the obligee; collection would be absurd by an insurer against an insured party, unless fraud was evident. Another difference is that insurance is easier to cancel than a bond. The insured can cancel insurance by simply notifying the insurer or by nonpayment of premium. Breach of the insurance contract by the insured or nonpayment of premium are the insurer’s frequent reasons for cancellation and a legal defense by the insurer to avoid liability. On the other hand, with a bond, the surety is liable to the beneficiary even though breach of contract or fraud occurred by the principal.

Fidelity Bond

Generally, a fidelity bond requires that an employee(s) be investigated to limit the risk of dishonesty for the insured. If the bonded employee violates the trust, the insurer (bonding company) indemnifies the employer (insured) for the amount of the policy.

Fidelity bonds may be of two kinds: (1) those in which an individual is specifically bonded, by name or by position, and (2) “blanket bonds,” which cover a whole category of employees.

Surety Bond

A surety bond essentially is an agreement providing for compensation if there is a failure to perform specified acts within a certain period of time. One of the more common surety bonds is called a contract construction bond. It guarantees that the contractor(s) involved in construction will complete the work that is stipulated in the construction contract, free from debts or encumbrances.

Several types of surety bonds are used in the judiciary system. A fiduciary bond ensures that persons appointed by the court to supervise the property of others will be trustworthy. A litigation bond ensures specific conduct by defendants and plaintiffs. A bail bond ensures that a person will appear in court; otherwise, the entire bond is forfeited.

Burglary, Robbery, and Theft Insurance

Understanding the definitions for burglary, robbery, and theft is important when studying insurance contracts. In reference to businesses, a valid burglary insurance claim requires the unlawful taking of property from a closed business that was entered by force. In the absence of visible marks showing forced entry, a burglary policy is inapplicable. Robbery is the unlawful taking of property from another by force or threat of force. Without force or threat of force, robbery has not occurred. Theft is a broad, catchall term that includes all crimes of stealing, plus burglary and robbery.

Despite the availability of insurance, crime against property is one of the most underinsured perils. Estimates are that less than 10% of loss to property from ordinary crime is insured. Risk assumption remains the often-used tool to handle the crime peril.

Federal Crime Insurance

The Federal Crime Insurance Program, established by Congress, began operation in 1971 to counter the difficulty of obtaining adequate burglary and robbery insurance, particularly in urban areas. The program was discontinued in 1995. Private insurers and their agents administered the coverage, and the federal government, through the Federal Insurance Administration, was the bearer of the risk.

Kidnapping and Extortion Insurance

Another form of crime insurance covers losses from a ransom paid in a kidnapping or through extortion. During the 1970s, an upsurge in domestic and international kidnappings and terrorism created a need for this form of insurance. U.S. banks and corporations with overseas executives are especially interested in this coverage. These policies cover executives, their families, ransom money during delivery to extortionists, and corporate negligence during negotiations, among other areas of coverage.

Higgins and Cullison (2005) report that the number of reported kidnappings worldwide is growing, although many of these crimes are unreported. In 2004, there were about 14,500 reported cases. What was once a problem concentrated in Latin America has become a global criminal enterprise. Unfortunately, in certain regions, a portion of ransom payments goes to police or security officials. Government no-ransom pronouncements are often followed by denials that a ransom was paid to free a hostage. The U.S. government has a policy of not paying ransom. However, American companies and individuals produce ransom and negotiate through intermediaries hired by insurers.

Terrorism Insurance

The Terrorism Risk Insurance Act of 2002 (TRIA) was passed by Congress to calm the insurance industry that faced claims resulting from the 9/11 attacks and concern over subsequent attacks. The act requires insurance companies to provide terrorism coverage to businesses willing to purchase it. Participating insurance companies pay out a claim (a deductible) before TRIA pays for the loss. TRIA losses are capped at $100 billion. The act is viewed as important to the U.S. economy to support recovery in the event of attacks. TRIA was set to expire at the end of 2005; however, President Bush signed a two-year extension. The extension raised industry deductibles and copayments to increase the insurance industry role in the program (BOMA Files, 2006: 20).

Cyber Insurance

Traditional insurance products often do not cover cyber risks. Thus, more and more insurers are offering businesses cyber insurance against risks such as viruses, denial of service attacks, theft of customer and proprietary information, and intellectual property disputes (France, 2006). Because this insurance field is developing as technology advances, the insured must be careful in selecting an insurer and understanding the definitions, terms, and limitations of these policies.

Cliff Hawkins, the newest member of Conway Excavation’s repair crew, pulled his rolling tool chest to a stop and extended his hand to his new supervisor.

“Well,” said Dave Greco, smiling and shaking Hawkins’s hand, “it looks like you brought everything but the kitchen sink.”

“A good mechanic can’t do much without a good set of tools,” replied Hawkins, patting the chest gently. “It took me five years and almost $3,000 to build up this set. Which reminds me”—he glanced around the garage—“if you expect me to leave these tools here, you’d better have some kind of security.”

“You’ve got nothing to worry about,” replied Greco. “We lock up at night, and nothing has ever been stolen yet.”

However, there is a first time for everything. A short time after Hawkins started working for Conway Excavation, the garage was broken into. Hawkins’s tools were stolen.

“I thought you said my tools would be safe here,” Hawkins fumed when he faced Greco.

“I never said that,” Greco corrected him. “I said this garage had never been broken into. And it hadn’t.”

“Yeah, well, I hope this company is prepared to reimburse me,” Hawkins said.

Greco sat up in his chair, surprised. “Reimburse you?” he echoed. “No way! You knew our security wasn’t very extensive, but you chose to leave your tools here anyway.”

“I had to leave my tools here,” Hawkins said angrily.

Greco shrugged. “Still, they were your tools and their loss isn’t this company’s responsibility.”

“We’ll see about that,” Hawkins said as he stormed out of the office.

Hawkins went to court to try to force Conway Excavation to reimburse him for his stolen tools. Did Hawkins get his money?

Make your decision; then turn to the end of the chapter for the court’s decision.

Fire Insurance

Historically, the fire policy was one of the first kinds of insurance developed. For many years, it has played a significant role in assisting society against the fire peril. Prior to 1873, fire insurance contracts were not standardized. Each insurer developed its own contract. Omissions in coverage, misinterpretations, and conflicts between insurer and insured resulted in considerable problems. These individualized contracts and resultant ambiguities caused the state of Massachusetts, in 1873, to establish a standard contract. Seven years later, the standard contract became mandatory for all insurance companies in the state. Today, except for minor variations in certain states, the wording of fire insurance contracts is very similar. However, in recent years, these standard fire policies have diminished in importance as broad coverage policies have increased in number.

An understanding of insurance rating procedures provides risk managers and loss prevention managers with the knowledge to propose investments in fire protection that can show a return on investment. Factors that influence fire insurance rates include the ability of the community’s fire alarm, fire department, and water system to minimize property damage once a fire begins. Class 1 communities have the greatest suppression ability, whereas Class 10 has the least. Strategies such as convincing the community to take steps to improve its grade and installing sprinkler systems in buildings can produce a return on investment (Williams et al., 1995: 341–345).

Property and Liability Insurance

Business Property Insurance

The building and personal property coverage form is one of several property forms developed by the ISO program. It covers physical damage loss to commercial buildings, business personal property (e.g., furniture, machinery, inventory), and personal property of others in the control of the insured. Additional coverage includes debris removal, pollutant removal, and fire department service charge. A cause-of-loss form is added to the policy to have a complete contract. A basic cause-of-loss form covers fire, lightning, explosion, windstorm or hail, smoke, aircraft or vehicles, riot, vandalism, sprinkler leakage, and other perils. A broader form can be selected to expand coverage to, for example, glass breakage and earthquake (Rejda, 2001: 268–274).

Another important kind of insurance is business income insurance (formerly called business interruption insurance). It indemnifies the insured for profits and expenses lost because of damage to property from an insured peril.

Liability Insurance

Legal liability for harm caused to others is one of the most serious risks. Negligence can result in a substantial court judgment against the responsible party. There are several kinds of exposures in the liability area for businesses. Relevant factors are the functions performed, relationships involved, and care for others required, such as the employee–employer relationship, a contract situation, consumers of manufactured products, and professional acts. Examples of liability exposures are bodily injury or death of customers, product liability, completed operations (i.e., faulty work away from the premises), environmental pollution, personal injury (e.g., false arrest, violation of right of privacy), sexual harassment, and employment discrimination.

In many jurisdictions, the law views the failure to obtain liability insurance against the consequences of negligence as irresponsible financial behavior. Mandatory liability insurance for automobile operators in all states is a familiar example.

Several kinds of business liability insurance are available. The commercial general liability (CGL) policy, developed by ISO, is widely used and can be written alone or as part of a CPP.

Workers’ Compensation Insurance

Workers’ compensation coverage includes loss of income and medical and rehabilitation expenses that result from work-related accidents and occupational diseases. An employer can obtain the coverage required by law through three possible avenues: (1) commercial insurance companies, (2) a state fund or a federal agency, or (3) self-insurance (i.e., risk assumption).

The Risk and Insurance Management Society (RIMS) publishes an annual Benchmark Survey (formerly called Cost of Risk Survey). The purpose of the survey is to provide an opportunity for risk managers to measure their organization’s risk management performance. The survey provides data to assist risk managers in structuring insurance programs, making cost comparisons to others in the same industry, and preparing recommendations to senior executives.

A major gauge in the survey is the cost of risk (COR) per $1,000 of revenue. The 2005 survey showed that the total cost of risk (TCOR) was down for the first time since 2001. Almost every industry showed a decrease in the median premium per $1,000 of revenue for 2005. Following the 9/11 attacks, insurance costs increased through 2003. In 2004, insurance costs fell in most lines, except for workers’ compensation, which caused a slight increase in TCOR. In 2005, the median TCOR fell about 11%. Despite Hurricanes Rita, Wilma, and Katrina, the property and casualty insurance industry earned about $55 billion in 2005 (Insurance Newsnet, 2006).

A vice president had been embezzling money from the Michigan Mining Corporation for several years, but Security Director Steve Douglas finally caught him. It was something of a Pyrrhic victory, however—the culprit was nabbed, but the company was out $135,000. Luckily, MMC had comprehensive business insurance that Douglas was sure would cover most of the loss.

The security director looked over the two policies, but they were poorly written and very confusing, so he called Lester Blank, the agent who handled the policies.

“I limped through the policies,” Douglas explained, “and I think I get the gist of them. MMC’s covered for $100,000, right?”

“Wrong,” Blank said. “The second policy replaced the first. You’re only covered for $50,000.”

Douglas was stunned, but he recovered quickly. “Now, wait a minute,” he said. “I may not have caught every mixed-up word in these policies, but the second one says we can collect on the first one for up to a year after its expiration date, provided the loss occurred during the time the first policy was in effect.”

“But the total limit is still $50,000,” insisted the insurance agent. “You’ll find a clause to that effect in the second policy, if you read carefully.”

“If I read carefully!” Douglas cried. “This second policy is so full of spelling and clerical errors that it’s anybody’s guess what it means. One look at this piece of slipshod writing and any court will side with us.”

Therefore, MMC went to court, claiming that because the policy was so complicated and poorly written, it should be interpreted in the company’s favor.

Did the court agree with MMC?

Make your decision; then turn to the end of the chapter for the court’s decision.

Claims

When an insured party incurs a loss, a claim is made to the insurer to cover the loss as stipulated in the insurance contract. For an insurance company, the settling of losses and adjusting differences between itself and the policyholder is known as claims management. Care is necessary by the insurer because underpayments can lead to lost customers, yet overpayments can lead to bankruptcy.

An insurance company investigation of a claim commonly includes (1) a determination that there has been a loss, (2) a determination that the insured has not invalidated the insurance contract, (3) an evaluation of the proof of loss, and (4) an estimate of the amount of loss. An example of item 2 occurs when the insured has not fulfilled obligations under the insurance contract, such as not protecting property from further damage after a fire or not adequately maintaining loss prevention measures.

Furthermore, most insurance contracts specify that the insured party must give immediate notice of loss. The purpose is to give the insurer an opportunity to study the loss before evidence to support the claim has been damaged. Failure to provide immediate notice may render the insurance invalid. The insured usually has 60 to 90 days to produce proof of loss. The insured is expected to provide accounting records, bills, and so on that might help in establishing the loss.

Before a settlement is reached, the insurer checks the coverage, the claim is investigated, and loss reports and claim papers are prepared. Then the insurance company claims department studies the loss, the policy is interpreted and applied to the loss, and a payment is approved or disapproved.

Insurance companies employ different classifications of adjusters to settle claims. An insurance agent (i.e. salesperson) may serve as an adjuster for small claims up to a certain amount. A company adjuster is more experienced about claims and handles larger losses. Independent adjusters offer services to insurance companies for a fee. Public adjusters represent the insured party for a fee.

From the insurance industry’s perspective, the work of an adjuster is demanding. A high priority is to satisfy claimants in order to retain customers. At the same time, the interests and assets of the insurance company must be protected. Some claimants make honest mistakes in estimating losses. They may place a value on destroyed property that is above the market value. Exaggerations are common. Confusion may arise when claimants have not carefully read their insurance policy. Consequently, a process of education and negotiation often takes place between the adjuster and the claimant. Once the claimant signs the proof of loss papers or cashes the settlement check, this signifies that the claimant is satisfied and that further rights to pursue the claim are waived. In a certain number of claims, an agreement is not reached initially. The policy states the terms for settling claims. Typically, arbitration results. Each party appoints a disinterested party to act as arbitrator. The two arbitrators then select a third disinterested party. Agreements between two of the three arbitrators are binding. In liability cases, the court takes the place of arbitrators.

Dishonest claimants are a serious problem for the insurance industry, and for society. Insurance fraud is pervasive and costly. Policyholders are the ultimate group that pays for these crimes through increased premiums.

Arson is unfortunately a popular way of defrauding insurance companies. Generally, a property owner sets a fire to collect on an insurance policy. A professional arsonist may be recruited. Law enforcement agencies and the insurance industry have increased efforts to combat arson through additional arson investigators, improved training, better detection equipment, and computers that search data for patterns of those who defraud insurance companies.

Claims for Crime Losses

A loss prevention practitioner or risk manager may be confronted with important decisions in a claim in an attempt to minimize losses for his or her employer. Although crime claims are emphasized here, several points are applicable to other types of claims.

When a person or business takes out an insurance policy to cover valuables, the insurance agent may not require proof that the valuables exist. However, when a claim is filed, the insurer becomes very interested in not only evidence to prove that the valuables were stolen (e.g., police report), but also evidence that the valuables in fact existed. Without proof, indemnification may become difficult. To avoid this problem, several steps are useful. First, the insured should prepare an inventory of all valuables. Accounting records and receipts are good sources for the inventory list. The list should include the item name, serial number, date it was purchased, price, and a receipt. Photographs and video of valuables are also useful. Copies should be located in two separate safe places.

Bonding Claims

Numerous insurance companies have found the fidelity bond business to be generally unprofitable. To compound the situation, businesspeople have attempted to used fidelity bond claims to cover losses from mysterious disappearance and general inventory shortages, rather than for their intended purpose—coverage for internal theft. For these reasons, when a claim takes place, the insurer and insured have a tendency to enter negotiations as adversaries. The strength of the loss prevention practitioner’s case will definitely affect the settlement. Care must be exercised throughout the interaction with the insurer so as not to in any way invalidate the contract. Furthermore, the burden of proof for losses rests entirely on the insured.

Before 1970, the insurer investigated applicants and notified the insured of any criminal history of the applicant that would bar coverage. Because of economy measures and the difficulty of checking into a person’s background, many insurers have made a shift to the insured for verifying the applicant’s past. Bonds stipulate that past dishonesty by the employee justifies an exclusion from bonding from the day the information is discovered; if a loss occurs and the insurer can prove that this information was known to the insured company but not reported to the insurer, the bond is likely to be invalid.

Another way to invalidate a bond is through restitution by the employee to the employer without notifying the insurer. In many cases, the employee is eager to pay back what was stolen but makes only a few payments before absconding. Thereafter, if a claim is made, the bond is useless.

In reference to the burden of proof, the loss prevention practitioner should have considerable expertise when dealing with the insurer on behalf of his or her employer. Confusion often arises from the “exclusionary clause” of the fidelity bond policy. This clause essentially states that the bond does not cover losses that are dependent on proof from inventory records or a profit and loss computation. Prior to 1970, these records were not even allowed to establish the extent of losses even though employees had confessed. However, in the early 1970s, courts began to be more flexible in limiting the exclusionary clause and thus allowing inventory records and associated computations to establish the amount of loss when independent proof also was introduced to establish that there was loss due to employee theft.

A confession is of prime importance to bonding claims. A guilty verdict in a criminal court or a favorable labor arbitration ruling are additional assets for the claimant.

What do you think are the most difficult challenges of a risk manager’s job?

Business Continuity

As we know, businesses and government face an enormous number of exposures to threats and hazards, and risk refers to the measurement of the frequency, probability, and severity of these exposures. Risk management helps business and government executives study and manage risks so they can prioritize risks and then plan and take action under limited budgets. Risk management is at the foundation of planning and action against risks. Business continuity is the term applied in the private sector (business) for planning and action against risks. Emergency management is the term applied in the public sector (government) for planning and action against risks. Here, we begin with a discussion of business continuity, and then we turn to emergency management to understand the role of government in emergencies.

Business continuity is defined by ASIS International (2004: 7) as follows: “A comprehensive managed effort to prioritize key business processes, identify significant threats to normal operation, and plan mitigation strategies to ensure effective and efficient organizational response to the challenges that surface during and after a crisis.”

The essence of business continuity is an up-to-date, comprehensive plan to increase the survivability of a business when it faces an emergency. Examples of topics in the plan are employee safety; IT backup; customer support; and limited, if any, recovery time. There is a lack of consistency in the private sector with business continuity planning. Top executives view and support it differently among businesses.

Many factors influence the success of business continuity. Examples are local infrastructure and the resources of public safety agencies. Because of recovery challenges following the 9/11 attacks, increased public-private sector cooperation has occurred.

Garris (2005: 28–32) writes that in our litigious society, organizations that fail to plan for emergencies could be held liable for injuries or deaths. He recommends learning about codes, regulations, and laws that are an essential foundation of plans. Sources include the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, the National Fire Protection Association, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Americans with Disabilities Act, as well as city and state authorities. Garris writes that 44% of all businesses that suffer a disaster never reopen.

Guidance for Business Continuity Planning

The NFPA 1600 Standard on Disaster/Emergency Management and Business Continuity Programs has been acknowledged by the U.S. Congress, American National Standards Institute (ANSI), and the 9/11 Commission. It has been endorsed by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the National Emergency Management Association, and others. This standard has been referred to as the “National Preparedness Standard” for all organizations, including government and business. NFPA 1600 serves as a benchmark of basic criteria for a comprehensive program, and it contains elements from emergency management and business continuity. There has been a convergence of these fields and a convergence of public and private sector efforts. Disasters (e.g., the 9/11 attacks) are showing the vital interdependencies of the public and private sectors.

The NFPA 1600 includes standards on program management, risk assessment, mitigation, training, and logistics, among other standards. It also contains definitions of terms and lists of resources and organizations.

The NFPA 1600 is not without its detractors (Davis, 2005). The Business Continuity Institute, located in the United Kingdom, claims that there is no business continuity document, and in NFPA 1600, business continuity is buried within emergency management. In addition, there are groups (e.g., ANSI) looking to the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) for enhanced business continuity standards.

The Business Continuity Guideline (ASIS International, 2004) offers an in-depth, multistep process for business continuity planning. It includes interrelated processes and activities that help in creating, testing, and maintaining an organizationwide plan for emergencies. Here is a sample of questions from the appendix of the guideline:

• Has your organization planned for survival?

• Is the business continuity plan up-to-date?

• Have the internal audit, security, and insurance units reviewed the plan?

• Has a planning team been appointed?

• Has a risk assessment been conducted?

• Have critical business processes been identified and ranked?

• Is technology (i.e., data, systems) protected?

• Have resources required for recovery been identified?

• Have personnel been trained and exercises conducted?

Another source for business continuity planning, especially for small and medium-sized businesses, is the Department of Homeland Security Web site www.ready.gov. It offers guidelines, sample emergency plans, tips for mail safety, security suggestions, and it uses an all-hazards approach.

Methodology for Business Continuity

Moskal (2006: 56–62), with an IT background, offers a business continuity management methodology to sort, summarize, and organize business requirements in a methodical manner. He writes that one barrier to planning and preparation is lack of support and funding from management. Citing a list of real world events that cost businesses billions of dollars, Moskal also supports his arguments for business continuity planning by referring to business survivability, cost of downtime (e.g., lost revenue, lost customers), penalties from contract stipulations on deadlines, and legal requirements (especially as a public company). His seven-step methodology is as follows:

1. Risk assessment report containing the identification of critical functions; business process threats and vulnerabilities, ranked by risk level; and risk-mitigating safeguards and costs.

2. Business impact analysis report containing critical business functions and workflow, qualitative and quantitative impacts of disruption, and recovery time objectives.

3. Disaster recovery plan containing resources, actions, and tasks to manage the recovery.

4. Business recovery plan containing advance plans, arrangements, and procedures for the complete recovery of business processes, including employees, workspace, equipment, and facilities.

5. Business resumption plan containing plans for continued availability of essential business processes and operations. It includes facility and operations management, as well as IT systems.

6. Contingency planning containing plans to respond to specific system or operation failures. Resources may include alternate work areas, reciprocal agreements, workaround procedures, and replacement resources.

7. Crisis management focuses on overall coordination of organizational response to a crisis to protect people and minimize damage to profitability, reputation, or ability to operate.

Persson (2005) sees the need for increased effort to provide quantitative, accurate, empirical reporting on how business continuity planning is working. He favors the use of metrics and lists the following benefits:

• They present activities in objective terms.

• Metrics help focus on issues. For example, if recovery time objective (RTO) is 6 hours on paper, but testing shows it is 24 hours, this issue needs to be addressed.

• It can be included in personnel objectives (i.e., responsibilities) and measured.

Here is a sample of metrics applicable to continuity planning from Persson’s IT perspective:

• Disaster recovery planning (DRP) as a percentage of total IT budget. This may be between 2% and 8%.

• Percentage of mission-critical applications covered. The goal should be to recover 100%.

• Total number of outages per year by category (e.g., power, network, virus).

Drawing on Persson’s IT work, metrics can be applied more broadly. Examples include the business continuity budget as a percentage of assets or revenue; the number of full-time employees (may be less than 1.0) who work on business continuity per $10 million of assets or revenue; and metrics can be compared within and among industries.

What do you think influences senior executive interest in business continuity planning?

Emergency Management

Bullock et al. (2006: 1–2) write that there is no single definition of emergency management because the discipline “has expanded and contracted in response to events, the desires of Congress, and leadership styles.” They note that emergency management “has clearly become an essential role of government” and the “Constitution entrusted the states with responsibility for public health and safety—hence, responsibility for public risks—and assigns the federal government to a secondary, supportive role. The federal role was originally conceived such that it intervenes when the state, local, or individual entities are overwhelmed.”

Bullock et al. (2006: 2) define emergency management as “the discipline dealing with risk and risk avoidance.” Here, we define emergency management as preparation for potential emergencies and disasters and the coordination of response and resources during such events.

McEntire (2004: 14–18) writes that the discipline of emergency management is going through a massive transformation. He refers to issues such as definitions of terms, what hazards to focus on, what variables to explore (e.g., location of buildings, building construction, politics, critical incident stress), and what disciplines should contribute to emergency management. McEntire notes that there is no single overarching theory of emergency management because it would be impossible to develop a theory that would contain every single variable and issue involving disasters. He sees systems or chaos theory as gaining recognition because they incorporate many causative variables. McEntire also offers other theories and concepts (below), that he views as relevant to emergency management. Notice the similarities in some of the following theories to those explained under risk management (i.e., risk perception theory; risk communication theory):

• Systems theory involves diverse systems that interact in complicated ways and impact vulnerability. These systems include natural, built, technological, social, political, economic, and cultural environments.

• Chaos theory has similarities to systems theory in that many variables interact and affect vulnerability. This theory points to the difficulty of detecting simple linear cause-and-effect relationships and it seeks to address multiple variables simultaneously to mitigate vulnerability.

• Decision theory views disasters as characterized by uncertainty and limited information that results in increased vulnerability to causalities, disruption, and other negative consequences. This theory focuses on perceptions, communications, bureaucracy, politics, and other variables that impact the aftermath of disasters.

• Management theory explains disasters as political and organizational problems. Vulnerability to disasters can be reduced through effective leadership and improved planning. Leaders have the responsibility to partner with a wide variety of players to reach objectives that reduce vulnerability.

• Organizational behavior theory sees agencies concerned about their own interests and turf, without understanding how their action or inaction affects others. Cultural barriers, a lack of communications, and other variables limit partnering to increase efficiency and effectiveness. Improved communications during the 9/11 attacks in New York City would have saved some of the lives of firefighters, police, and others.

• Risk perception and communication theory focuses on the apathy of citizens prior to disasters. Vulnerability can increase if citizens do not understand the consequences of disasters and do not take action for self-protection (e.g., evacuation). Citizens may be more likely to reduce their vulnerability if authorities communicate risk accurately and convincingly.

• Social constructionist theory shifts from hazards that we cannot control to the role of humans in disasters, who determine through decisions the degree of vulnerability; for example, citizen decisions to reside in areas subject to mudslides.

• Weberian theory looks to culture—including values, attitudes, practices, and socialization—as contributing to increased vulnerability. Other factors under this theory resulting in greater vulnerability are weak emergency management institutions and a lack of professionalization among emergency managers.

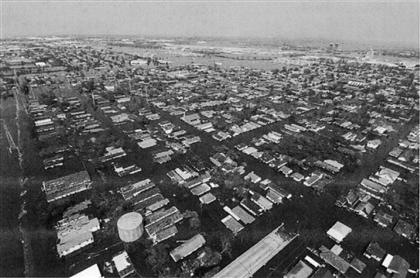

• Marxist theory explains economic conditions and political powerlessness as playing roles in disaster vulnerability. The poor and minorities are more likely to reside in vulnerable areas and are often unable to act to protect themselves. The Hurricane Katrina disaster serves as an example; thousands of citizens were trapped in flooded New Orleans, which was built below sea level.

Risk Management in Government

Risk management is as important in the public sector as it is in the private sector. Risk management helps government executives study and manage risks so they can prioritize risks and then plan and take action under limited budgets. For government, exposures and risks are enormous and broad—affecting local, state, national, and global levels. Examples include liability, crime, workers’ compensation, fire, war, terrorism, proliferation of weapons of mass destruction (WMD), disease and pandemics, natural disasters, conflicts over natural resources, and issues of migration.

Although the private sector, especially the insurance industry, has played a lead role in advancing the discipline of risk management, local and state governments are increasingly employing risk management methods. The Public Risk Management Association (PRIMA), the largest network of public risk management practitioners, states: “Risk management in the public sector finds itself at a challenging moment in time.” “… [T]here is a very high level of interest in the subject, but a lack of clarity and consistency as to its meaning, form and purpose.” The group sees pockets of advanced risk management practice in the United States; however, most small government entities do not have a formal risk management unit. PRIMA sees various segments of the discipline spread among departments in government (e.g., insurance, purchasing, finance) and efforts to unify the function under the emerging concept of enterprise risk management have just begun in the public sector (Public Risk Management Association, 2003).

On the federal government level, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), a federal “watchdog,” is a strong proponent of risk management. It has argued for risk management to be applied at all levels of government, including the Departments of Homeland Security and Defense and the FBI. The U.S. Government Accountability Office (2005: 124–125) stated: “… [A] vacuum exists in which benefits of homeland security investments are often not quantified and are almost never valued in monetary terms.” The GAO argues for criteria for quantifiable and nonquantifiable benefits of homeland security spending so analysts can develop information to inform management.

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security (2004c: 54) stated: “We will guide our actions with sound risk management principles that take a global perspective and are forward-looking. Risks must be well understood, and risk management approaches developed, before solutions can be implemented.”

All-Hazards Preparedness Concept

“All hazards” include natural disasters (e.g., hurricanes, earthquakes) and human-made events (e.g., inadvertent accidents, such as an aircraft crash, and deliberate events, such as the terrorist bombing of an aircraft). Another category is technological events (e.g., an electric service blackout resulting from a variety of possible causes). FEMA (2004) states: “The all-hazards preparedness concept is simple in that how you prepare for one disaster or emergency situation is the same for any other disaster.” The all-hazards approach is important because it plays a role in preventing our nation from over-preparing for one type of disaster at the expense of other disasters (Figure 12-2).

FIGURE 12-2 The U.S. government is working to provide an all-hazards response capability.Courtesy: U.s. Department of Homeland Security.

It is argued here that the all-hazards approach seeks to maximize the efficiency and cost effectiveness of emergency management efforts through a realization that different disasters contain similarities that can benefit, to a certain degree, from generic approaches to emergency management. This includes generally similar emergency services, equipment, and products. Conversely, there is a point at which generic emergency management must divide into specialized emergency management. For example, the detonation of a “dirty-bomb” or an approaching hurricane necessitates evacuation; however, the victims and the scene of these disasters require markedly different expertise, treatment, and equipment.

The History of Emergency Management

Haddow and Bullock (2003: 1–13) traced the development of emergency management as described next. The first example of the federal government becoming involved in a disaster was when, in 1803, a Congressional Act was passed to provide financial assistance to a New Hampshire town that was destroyed by fire. During the Great Depression (1930s), President Franklin D. Roosevelt spent enormous federal funds on projects to put people to work and to stimulate the economy. Such projects had relevance to emergency management. The Tennessee Valley Authority was created to not only produce hydroelectric power, but to reduce flooding.

During the 1950s, as the Cold War brought with it the threat of nuclear war, Civil Defense Programs grew. These programs were characterized by communities and families building bomb shelters as a defense against attack from the Soviet Union. Air raid drills became common at schools; children practiced going under their desks or kneeling down in the hall while covering their heads. Civil defense directors, often-retired military personnel, were appointed at the local and state levels, and these individuals represent the beginning of emergency management in the United States. The Federal Civil Defense Administration (FCDA) provided technical assistance to local and state governments. Another agency, the Office of Defense Mobilization (ODM), was established in the Department of Defense (DOD) to quickly amass materials and production in the event of war. In 1958, both the FCDA and the ODM were merged into the Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization.

A series of destructive hurricanes in the 1950s resulted in ad hoc Congressional legislation to fund assistance to the affected states. The 1960s also saw its share of natural disasters that resulted in President John F. Kennedy’s administration, in 1961, creating the Office of Emergency Preparedness to deal with natural disasters. The absence of flood insurance on the standard homeowner policy prompted Congress to enact the National Flood Insurance Act of 1968, which created the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). This noteworthy act included the concept of community-based mitigation, whereby action was taken against the risk prior to the disaster. When a community joined the NFIP, the program offered federally subsidized, low-cost flood insurance to citizens in exchange for the community enacting an ordinance banning future development in its floodplains. As a voluntary program, the NFIP was not successful. The Flood Insurance Act of 1972 created an incentive for communities to join the NFIP. This act required mandatory purchase of flood insurance for homeowner loans backed by federal mortgages, and a significant number of mortgages were federally backed.

The 1970s brought to light the fragmentation of federal, state, and local agencies responsible for risk and disasters. Over 100 federal agencies added to the confusion and turf wars. Unfortunately, the problems were compounded during disasters. The administration of President Jimmy Carter sought reform and consolidation of federal emergency management. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) was established by Executive Order 12127 on March 31, 1979. The goal of this effort was to consolidate emergency preparedness, mitigation, and response into one agency, with a director who would report directly to the president. John Macy, who was in the Carter cabinet, became the director of FEMA. He emphasized similarities between natural hazards preparedness and civil defense and developed an “all-hazards” approach containing direction, control, and warning as goals common to all emergencies.

Through the 1980s, FEMA experienced numerous troubles and criticism. The top priority of FEMA became preparation for nuclear attack, at the expense of other risks. Environmental cleanup (e.g., Love Canal) became another priority. States saw their funding for emergency management decline. By the end of the 1980s, FEMA was in need of serious reform. FEMA’s problems included tension with its partners at the state and local level over priorities and funding, and difficulty in responding to natural disasters. In 1989, Hurricane Hugo became the worst hurricane in a decade and caused 85 deaths and damage of more than $15 billion as it slammed into South Carolina, North Carolina, and other locations. The FEMA response was so poor that Senator Ernest Hollings (D-SC) called the agency the “sorriest bunch of bureaucratic jackasses.” The FEMA problems with Hurricane Andrew, in 1992, in Florida, further eroded confidence in the agency.

Reform in FEMA finally occurred in 1993 when President William Clinton nominated James L. Witt, of Arkansas, to be director. Witt was the first director with emergency management experience, and he was skilled at building partnerships and serving customers. Inside FEMA, Witt fostered ties to employees, reorganized the agency, and supported new technologies to deliver disaster services. Externally, he improved relationships with state and local governments, Congress, and the media. Subsequent disasters, such as the Midwest floods in 1993 that resulted in nine states being declared disaster areas and the Northridge, California, earthquake in 1994, tested the reforms FEMA had made. Witt was elevated to be a member of President Clinton’s cabinet, illustrating the importance of emergency management. Witt then sought to influence the nation’s governors in elevating state emergency management directors to cabinet posts.

The World Trade Center bombing in 1993 and the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995 brought the issue of terrorism to the forefront of emergency management. A major question surfaced: Which agency would be in charge following a terrorist attack? Prior to the 9/11 attacks, several federal agencies sought leadership against terrorism. Major agencies included FEMA, the Department of Justice (DOJ) (it contains the FBI), the DOD, the National Guard, and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Coordination was poor as agencies pursued their own agendas. The DOD and the DOJ received the most funds. State and local governments felt unprepared and complained about their vulnerabilities and needs. The 9/11 attacks resulted in a massive reorganization of the federal government and the creation of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to better coordinate both actions against terrorism and homeland security.

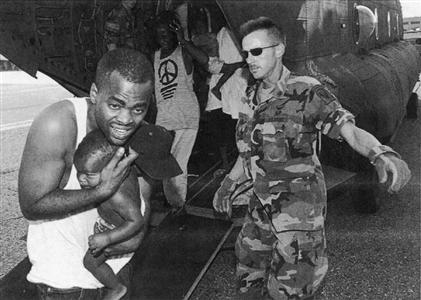

In September of 2005, FEMA experienced another setback when its director, Michael Brown, was relieved as commander of Hurricane Katrina (Figure 12-3) relief efforts along the Gulf Coast, and he was sent back to Washington, D.C. Three days later, he resigned. Critics argued that he was the former head of an Arabian horse association and that he had no background in disaster relief when his friend and then-FEMA Director, Joe Allbaugh, hired him in 2001 to serve as FEMA’s general counsel. Although “finger-pointing” occurred by politicians at all levels of government as the relief effort became overwhelmed, Michael Brown became the classic scapegoat. Following the Katrina disaster, there were calls for reform of FEMA.

FIGURE 12-3 In 2005, Hurricane Katrina flooded sections of New Orleans, left hundreds of thousands of people homeless, and overwhelmed government response.Courtesy: Gary Nichols, Dod.

Emergency Management Disciplines

Haddow and Bullock (2003) divide emergency management into the disciplines of mitigation, response, recovery, preparedness, and communications. Although they emphasize natural hazards, their writing provides a foundation for multiple risks.

Mitigation

Haddow and Bullock (2003: 37) define mitigation as “a sustained action to reduce or eliminate risk to people and property from hazards and their effects.” It looks at long-term solutions to reduce risk, as opposed to preparedness for emergencies and disasters.

Mitigation programs require partners outside traditional emergency management. Examples are land-use planners, construction and building officials, and community leaders. The tools of mitigation include hazard identification and mapping and building codes.

Response

Response includes activities that address the short-term, direct effects of an incident, and it seeks to save lives, protect property, and meet basic human needs. Depending on the emergency, response can entail applying intelligence to lessen the effects or consequences of an incident; increased security; investigations; public health and agricultural surveillance and testing processes; immunizations, isolation, or quarantine; operations to disrupt illegal activity; and arresting offenders. First responders at emergencies and disasters are usually local police, fire, emergency medical specialists, and not state or federal personnel. Besides local, state, and federal responses, volunteer organizations and the business community respond to emergencies and disasters.

All 50 states and six territories of the United States operate an office of emergency management. The names of these offices vary, as does the placement in the organizational structure of each jurisdiction. National Guard Adjutant Generals lead these offices in most states, followed by leadership by civilian employees. Governors rely primarily on their state National Guard for responding to disasters. National Guard resources include personnel, communications systems, air and road transport, heavy construction equipment, mass care and feeding equipment, and assorted supplies (e.g., tents, beds, blankets, medical). When a state is overwhelmed by a disaster, the governor may request federal assistance under a presidential disaster or emergency declaration.

The Homeland Security Act of 2002 established the DHS to reduce our nation’s vulnerability to terrorism, natural disasters, and other emergencies, and to assist in recovery. The Secretary of Homeland Security is responsible for coordinating federal operations in response to emergencies and disasters.

Recovery

Recovery involves actions to help individuals and communities return to normal. It serves to restore infrastructure, basic services, government, housing, businesses, and other functions in a community. Haddow and Bullock (2003: 95) view the goal of effective recovery as bringing all the players together to plan, finance, and prepare a recovery strategy. Besides action by all levels of government, recovery includes the role of the insurance industry, which provides financial support. However, the federal government plays the largest role in technical and financial support for recovery. The range of grant and assistance programs that the federal government has been involved in over the years, especially through FEMA, has been enormous and cost tens of billions of dollars.

Preparedness

Before a disaster strikes, preparation is vital. Preparedness includes risk management to identify threats, hazards, and vulnerabilities. Then all levels of government and the private sector plan and prepare for disasters through planning, training, exercises, and identifying resources to prevent, protect against, respond to, and recover from disasters. Preparedness is the job of everyone and all sectors of our society.

Communications