Section IX: Borderline Personality

Am I Comparing My Insides with Other People's Outsides?

Goals of the Exercise

1. Replace dichotomous thinking with the ability to tolerate ambiguity and complexity in people and issues.

2. Learn and practice interpersonal relationship skills.

3. Come to an awareness and acceptance of angry feelings while developing better control and more serenity.

4. Become capable of self-monitoring, identification of cognitive distortions (e.g., all-or-nothing thinking, catastrophizing, and unrealistic perceptions of self and others), and replacement of these distorted thoughts with more accurate and constructive cognitions leading to reduction of self-destructive behaviors.

Additional Problems for which this Exercise may be Useful

- Adjustment to the Military Culture

- Anger Management and Domestic Violence

- Conflict with Comrades

- Social Discomfort

- Substance Abuse/Dependence

Suggestions for Processing this Exercise with Veterans/Service Members

The “Am I Comparing My Insides with Other People's Outsides?” activity may be especially useful with veterans/service members who display borderline tendencies rooted in distorted perceptions or expectations about themselves and others in relationships, leading to self-sabotaging and self-destructive behaviors. Follow-up can consist of bibliotherapy using books suggested in Appendix A of The Veterans and Active Duty Military Psychotherapy Treatment Planner and/or videotherapy using films suggested for the topic “Substance Abuse” in Rent Two Films and Let's Talk in the Morning, 2nd ed., by John W. Hesley and Jan G. Hesley, also published by John Wiley & Sons.

EXERCISE IX.A Am I Comparing My Insides with Other People's Outsides?

This exercise is about patterns that many of us have in our interactions with other people, patterns that don't work very well for us and may make it difficult or impossible for us to have stable, rewarding relationships. The same patterns may also make it harder for us to maintain our own emotional stability and lead us to self-destructive behavior of many kinds. These patterns are the results of distorted ways of thinking too negatively about ourselves and more idealized than is realistic about others. By working through this exercise, you can become more skilled at identifying and testing your judgments about yourself and others, testing those judgments to see whether they're really accurate, and correcting them if necessary.

1. You may or may not have heard the phrase in this exercise's title. Please take a moment to think about it and what it might mean. What do you think it would mean to compare your insides with other people's outsides?

_____

_____

_____

2. It's a term some people use for the habit of seeing other people as being calm, confident, and secure in interpersonal situations or in crises, while they see themselves as nervous, clumsy, and tongue-tied in the same situations. Please think of a recent personal experience such as this and briefly describe it—when and where did it take place, what was going on, and with whom were you comparing yourself?

_____

_____

_____

3. What terms would you use to describe how you felt, and how you perceived the other person?

Yourself: _____

The other person: _____

4. What evidence did the other person's behavior, expression, and body language give you to tell you how he or she was actually feeling—what did you see and hear?

_____

_____

5. What do you think you would have been feeling and thinking about yourself if you had been in his or her place in the same situation?

_____

_____

6. Now think of a situation in which you felt scared, embarrassed, confused, insecure, and/or overwhelmed, but on the outside, to others, you looked confident, relaxed, and competent. Briefly describe that situation and what you were doing to give people that impression:

_____

_____

Do you think that sometimes other people are doing the same thing, that they look good on the outside but feel pretty miserable on the inside? _____

7. Take a moment to think about a person in your life that you admire and respect, and then think of a situation in which he or she was experiencing all of those painful thoughts and judgments about himself or herself. What was the situation, and what did he or she do about it? Do you respect this person less because he or she has sometimes felt this way?

_____

_____

8. If the person you respect used an effective strategy to cope with painful thoughts and feelings about himself or herself, could you use the same strategy? How would you do that?

_____

_____

To change these patterns, it helps to work at becoming your own friend rather than your own meanest critic. To do this, monitor what you feel and say to yourself—try carrying a small notepad, and when you feel bad about yourself, stop and write down four things: (1) what the situation is, (2) what you're saying to yourself, (3) whether it's accurate, and (4) whether you'd say the same thing to a friend who was in your situation. If the answer to (4) is “no,” write down what you would say to your friend instead. Often we mix up a negative judgment about an action with a negative judgment about ourselves, and it's important not to mix up what we do with who we are.

Be sure to bring this handout back to your next session with your therapist, and be prepared to discuss your thoughts and feelings about the exercise.

I Can't Believe Everything I Think

Goals of the Exercise

1. Replace dichotomous thinking with the ability to tolerate ambiguity and complexity in people and issues.

2. Develop and demonstrate anger management skills.

3. Learn and practice interpersonal relationship skills.

4. Reduce the frequency of maladaptive behaviors, thoughts, and feelings that interfere with attaining a reasonable quality of life.

5. Identify, challenge, and replace biased, fearful self-talk with reality-based, positive self-talk.

Additional Problems for which this Exercise may be Useful

- Anger Management and Domestic Violence

- Anxiety

- Conflict with Comrades

- Phobia

- Social Discomfort

- Suicidal Ideation

- Survivor's Guilt

Suggestions for Processing this Exercise with Veterans/Service Members

The “I Can't Believe Everything I Think” activity is designed for use with veterans/ service members who present with the cognitive distortions, emotional lability, and difficulty in relationships common to people suffering from borderline personality traits. The approach this exercise uses is the classic method found in cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT), and cognitive processing therapy (CPT). Follow-up or concurrent treatment activities could include bibliotherapy using one or more of the books listed for this issue in Appendix A of The Veterans and Active Duty Military Psychotherapy Treatment Planner and/or videotherapy using films suggested for the topic of “Emotional and Affective Disorders” in Rent Two Films and Let's Talk in the Morning, 2nd ed., by John W. Hesley and Jan G. Hesley, also published by John Wiley & Sons.

EXERCISE IX.B I Can't Believe Everything I Think

Most of us find ourselves getting upset—angry, worried, or depressed—over things that happen in our day, and we tend to assume that the events caused the feelings. That can also leave us feeling vulnerable and helpless, with our happiness and peace of mind at the mercy of people and situations beyond our control. That's not quite how it really works, though—the process is a bit more complex—and by gaining an understanding of how our experiences, thoughts, and feelings really work, we can have much more power over our quality of life. This activity will walk you through a strategy to take charge of your own emotional life.

1. The most important fact in this process is this: The events in our lives do not lead directly to our emotional responses. There is a step in between, and that step is the thought we have about the event or the situation—the thoughts are what generate the emotions, and a lot of unhappiness is caused by mistakes in those thoughts. When you've completed this exercise, you will have a handy way to check for those mistakes, correct them, and improve your quality of life. Here's an example: Suppose Person A is entering a grocery store and sees a friend, Person B, coming out. A smiles, nods to B, and starts to greet him, but B walks past A without acknowledging him and is already walking down the sidewalk before A has a chance to say hello. What would Person A's immediate reaction be?

_____

For a lot of people, the reaction would be for Person A to feel angry and hurt at being given the cold shoulder by Person B. But notice the way that this is being expressed—the anger and hurt is a response to being deliberately ignored by the friend.

But is that what really happened? The truth is, with the information from this event, it's impossible to be sure. What are some other reasons that might be behind the behavior of Person B in this scenario?

_____

_____

_____

2. It probably wasn't hard for you to come up with some alternative explanations: what if Person B had lost his contact lenses and just didn't recognize Person A? What if Person B had just gotten a call on his cell phone telling him a family member had been in a car crash and was in the emergency room? What if he had a migraine headache and was in enough pain to keep him from noticing Person A? None of those would be reason for Person A to be angry or hurt at all. Those emotions actually came from a couple of thinking mistakes: in this case, the mistakes were jumping to a conclusion and assuming that Person B's behavior was about, or focused on, Person A, when in reality it might have had nothing to do with him.

3. There are many other common thinking mistakes, or as they're also called, cognitive distortions. Here are some that most of us engage in at times:

a. All-or-nothing, good-or-bad thinking—this is when we think of a person or a situation as unrealistically idealized or terrible. This in turn sets us up to form unrealistic expectations and be surprised and upset when people we had idealized turn out to be flawed and only human. People and situations are always a mix of good and bad.

b. Emotional reasoning—we make this mistake when we listen to our emotions and accept how we feel about ourselves, other people, or situations as reality. For example, if a person has failed at one task and is feeling humiliated, that person might believe that he or she is completely incompetent, or feel that others see him or her that way.

c. Overgeneralizing—for example, meeting a person from New York who is pushy and loud, and deciding that all New Yorkers are pushy and loud.

d. Mind-reading—assuming we know what others are thinking or feeling, espe-cially their motives for their actions or what they think of us.

e. Fortune-telling—predicting future events, or future actions by other people, when we don't really know what will happen.

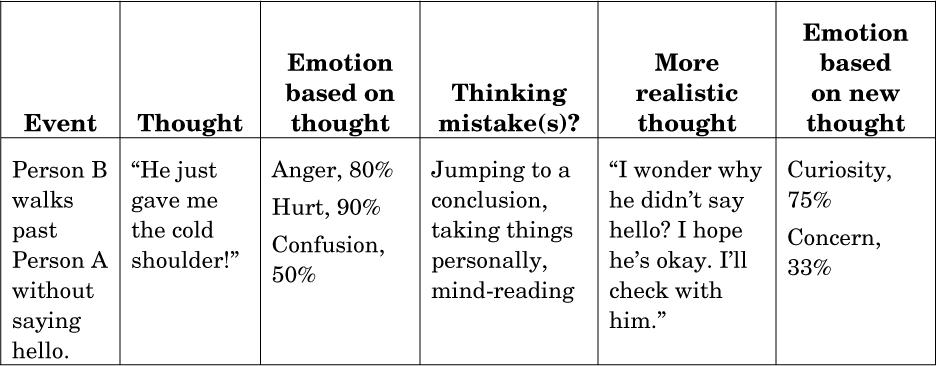

4. Those are some of the mistakes but there are quite a few more. The important thing is to recognize that all human beings are prone to these kinds of thinking errors. We need to dig out the thoughts underlying our emotions and see whether they really make sense. To analyze any situation divide a sheet of paper into six columns. In Column 1 describe what happened; in Column 2, write any thoughts you had about the event in Column 1; and in Column 3, write the emotion or emotions you felt as a result of the thought in Column 2, rating the emotion's intensity from 1% to 100%.

In Column 4, list any mistakes or distortions you can see in the thought in Column 2 as it relates to the event in Column 1. In Column 5, write a more realistic thought that is solidly based on the facts you have (this thought will often be neutral or positive when the thought in Column 2 was negative). And in Column 6, write the emotions you now feel after filling out Columns 4 and 5, and again rate the intensity of the emotion from 1% to 100%. Here's an example, using the scenario from earlier in this activity:

For most of us, the emotions in the last column will cause much less distress. So try practicing this at least once a day, and you may find you like the results enough that it will be habit-forming.

Be sure to bring this handout back to your next session with your therapist, and be prepared to discuss your thoughts and feelings about the exercise.