Anansi, the great spider of venerable memory, gathered all of the world’s wisdom into a gourd. Seeking to safeguard this wisdom for future generations, he hung the gourd high in a tree. But he failed. The gourd fell and broke, and wisdom was scattered far and wide.

Unumbotte made a human being. Its name was Man. Unumbotte next made an antelope, named Antelope. Unumbotte made a snake, named Snake. At the time these three were made there were no trees but one, a palm. Nor had the earth been pounded smooth. All three were sitting on the rough ground, and Unumbotte said to them: “The earth has not yet been pounded. You must pound the ground smooth where you are sitting.” Unumbotte gave them seeds of all kinds, and said: “Go plant these.”

OUR AWARENESS OF AFRICA BEGINS as the place where our hominid ancestors evolved. But it remains a “Dark Continent” in terms of broader understanding of what African peoples accomplished in the millennia preceding the transatlantic slave trade, when the continent’s history again comes into focus for modern audiences. Unexamined views of Africa carry the presumption of a continent on the sidelines of world history, where little occurred until the Atlantic slave trade swept away millions of its people. In the New World, so these views maintain, Europeans taught their unskilled bondsmen to plant crops and tend animals. Nevertheless, one of the remarkable achievements of Africans over the past ten thousand years was the independent domestication of plants and animals for food. These African species journeyed to Asia in the second and first millennia B.C.E. and, later, profoundly shaped the food systems of plantation societies of the Americas.1

The African continent harbors more than two thousand native grains, roots and tubers, fruits, vegetables, legumes, and oil crops. Its plant resources also provide stimulants, medicines, materials for religious practices, and fodder for livestock. Long before Muslim caravans and Portuguese caravels reached the African continent, its peoples initiated the process of plant and animal domestication. Africans have contributed more than one hundred species to global food supplies.2 The plants they gave the world include pearl (bulrush) millet, sorghum, coffee, watermelon, black-eyed pea, okra, palm oil, the kola nut, tamarind, hibiscus, and a species of rice. Widely known consumer products—Coca-Cola, Palmolive soap, Worcestershire sauce, Red Zinger tea, Snapple and most soft drinks—rely in part on plants domesticated in Africa.3 African contributions to global plant history, however, are largely unacknowledged and seldom appreciated. In the popular image, Africa is a place of hunger and starvation, a continent long kept alive by food imported from other parts of the world.

But this modern perception belies a very different history. In ancient times, African cereals transformed the food systems of semiarid India by providing grain and legumes suitable for cultivation. Domestication of animals and plants in Africa thousands of years ago instigated a continuing process of indigenous experimentation and innovation, a process that incorporated species later introduced from other continents. From these immigrant species, Africans developed new cultivars and breeds that strengthened the capacity of food systems to provide daily subsistence. By the time Europeans visited the west coast of Africa in the fifteenth century, they found a land whose bounty provoked admiring commentary. In the words of the seventeenth-century Luso-African trader Lemos Coelho: “The blacks have many foodstuffs such as [guinea] hens, husked rice (all high-quality and cheap), plenty of milk, and excellent fat (manteiga, ‘butter’)…. This is because the whole kingdom of Nhani is full of villages of Fulos [Fula], who have these foodstuffs in abundance. A cow costs only a pataca or its equivalent…. Thus everything necessary for human existence is found in this land in great plenty and sumptuousness.”4

Even as the transatlantic slave trade removed millions of people from the continent, African societies produced food surpluses. And in the Americas, enslaved Africans continued their innovating processes. They nurtured Africa’s principal dietary staples in their food fields and adopted Amerindian crops beneficial to their survival. Livestock-raising peoples such as the Fula brought animal-husbandry skills that contributed critically to New World ranching traditions.

Human beings evolved in Africa. Fully modern humans, Homo sapiens sapiens—people like us with full syntactical language—emerged from the African ancestral line of all living humans between 100,000 and 60,000 years ago.5 This evolutionary development probably took place in the eastern parts of Africa. With their new capacity for language, these first true humans soon spread across the continent. Later, between 60,000 and 50,000 years ago, a small group of these fully human hunter-gatherers left Africa. They expanded outward from northeast Africa following one, possibly two routes: with watercraft along the Indian Ocean shores of southern Asia and by foot across the Sinai Peninsula into the Middle East.6 The descendants of these African emigrants eventually settled most of the habitable regions of the world, giving rise to the human populations that we recognize today.

The DNA of human cells preserves a biological record of this remarkable global journey. Two different genetic signatures—one from the DNA of cellular mitochondria (mtDNA) and the other from the Y-chromosome that confers maleness—offer compelling scientific evidence for humanity’s “out of Africa” origins. MtDNA is exclusively inherited from our mothers, so mutations pass intact from one generation to the next through the female line. The extent of change or variation on a strand of mtDNA may be quantified by chemical analysis. Through this technique, mtDNA provides geneticists a tool for measuring the evolutionary distance between the original African population of human beings who evolved on the continent and those descended from the small group who formed its primordial diaspora. Scientific studies of the human genome show that a nearly full diversity of all mtDNA variation occurs in the populations of Africa. MtDNA lineages found in humans outside Africa belong to one subset of that diversity. A similar pattern characterizes the Y-chromosome, which men inherit directly from their fathers. Y-chromosome lineages found outside Africa comprise one subset among all the Y-chromosome lineages found among Africans. The subsets of mtDNA and Y-chromosome lineages found in humans outside the continent are most typical of northeastern African populations. This supports the conclusion that human populations of the rest of the world originated through the migration of peoples out of that part of the continent. Africa is indelibly imprinted in the genetics of all human beings.

One of the greatest achievements of human beings was the domestication of plants and animals. Just as the earliest Homo sapiens sapiens of 90,000 to 60,000 years ago coped with different environments as they spread across Africa, so did their descendants who fanned out across the rest of the globe after 60,000 years ago. The African emigrants encountered diverse new environments in which they discovered edible plants and new animal food sources. On grasslands, river floodplains, highlands, marshes and coastal estuaries, they hunted animals and birds, took fish from bodies of water, gathered wild plants, and uprooted edible tubers. In distinctive environmental settings, humanity began the long process of manipulating species for their food, medicines, and spiritual needs. Some ten thousand years ago the process of plant and animal domestication was simultaneously underway in several parts of the world, including Africa.

Africa is the world’s second-largest continental landmass after Asia. Three times the size of Europe and larger than North America, Africa is nearly an island. Just a sliver of land connects the continent to the Sinai Peninsula and the Near East. It is a sprawling continent, extending across 72 degrees of latitude. Most of its landmass falls within the tropics, between the defining lines known as the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn. The equator cuts the continent into two unequal halves: from Tunisia lying 37 degrees latitude north to Cape Town at 34 degrees south, the distance traversed is equivalent to that between New York and Hawaii. Within these vast geographical extremes, life, settlement, and livelihood strategies have been adapted to heterogeneous landscapes.

Africa is a mostly tropical continent, but it is also a savanna continent. The most extensive areas of savanna in the world are presently found in Africa south of the Sahara Desert. These grasslands cover areas of low topographic relief that include diverse types of environments. Their vegetative profile varies with rainfall, soil type, and human activities. Some savannas are well watered, others not. This gives them their distinctive appearance, which ranges from thickly wooded grasslands to nearly treeless plains. Many of Africa’s principal food crops were domesticated in these variegated landscapes.

The savanna environment is also in part the result of human agency. Africa’s savannas have long been manipulated by fire, both natural and human-made. In the thousands of years prior to the onset of the domestication of wild species, human beings used fire to drive game animals in desired directions. Burning also encouraged the growth of nutritious grass shoots that became forage for wild animals. When ancient peoples discovered this, they exploited the practice to improve the survival of the game they hunted. Today no other environment on the face of the earth supports animals of such spectacular size or herds of such immense numbers. Africa is often called the living Pleistocene precisely because of the game animals that thrive on its savannas.

Research from a number of disciplines suggests that Africa’s pathway to food production may have been unique among world regions where the domestication of plants and animals took place. Archaeological, genetic, botanical, and linguistic studies indicate that the earliest African food producers were likely mobile herders rather than sedentary plant gatherers. In contrast with other regions of the globe, the domestication of animals in Africa apparently preceded that of plants.7

FIGURE 1.1. Cattle herd from Tassili Jabberen rock art, ca. 4000 B.C.E.

SOURCE: Lhote, Search for the Tassili Frescoes, pl. 27.

Africans began the process of plant and animal domestication around 10,500 B.P. From the last glacial maximum some 20,000 years ago to the close of the ice ages, the Sahara was hyperarid, even more so than it is today. After 10,500 B.P. the Sahara’s climate became wetter. In the eastern Sahara this transformation was both abrupt and dramatic. For three thousand years, from 8500 to 5300 B.C.E., summer rains from the Atlantic airflow system periodically reached the region.8 In the Nubian Desert of southern Egypt, a large basin known as the Nabta Playa began filling with water. The unpredictable rains and frequent droughts during this climatic phase made the emergent lake an attraction for animals and human beings. The earliest settlements at Nabta, some 10,500 to 9,300 years old, suggest the inhabitants were cattle-keeping people.9

The oscillating wet and dry periods that marked the early Holocene may have encouraged hunter-gatherers to domesticate cattle as a food source.10 The uncertainties of environmental change and the need for more dependable food supplies perhaps prompted ancient Africans to embark upon the domestication of the wild cattle species, Bos primigenius africanus. The oldest undisputed remains of domesticated cattle in the eastern Sahara date to 8,000 years ago. However, the Nabta evidence suggests that domestication may have taken place between 10,500 and 9,000 B.P., more than a millennium earlier. Recent data from archaeology, historical linguistics, and DNA analysis now support a claim for an independent domestication of humpless longhorn cattle in the eastern Sahara at an early date.11

Cattle tending spread westward across Saharan grasslands and south to the Red Sea Hills.12 Rock art of the western Sahara indicates that pastoralists diffused across the savannas of the Sahara between 8,000 and 6,000 B.P. (figure 1.1).13 Around 5300 B.C.E., a decisive climate shift in the eastern Sahara promoted a gradual desiccation. The original area of cattle domestication in turn grew less hospitable to herders. The cessation of summer rains once again brought hyperaridity to the region. Pastoralists responded by moving their cattle herds to wetter savanna environments. The return of desert conditions in Egypt about 3500 B.C.E. coincided with the initial period of the pharaonic civilization, centered on the Nile River floodplain. By then the entire Saharan region was trending toward decreased precipitation.14

As aridity once again returned to the Sahara, lakes and water holes on the grasslands that had made the region attractive to game animals, hunter-gatherers, herders, and fishing peoples dried up. Eventually, rainfall declines shaped the Sahara into the arid landscape that it is today. Domesticated livestock provided herders a reliable subsistence strategy, as people and animals followed the patchy retreat of savannas to the verdant grasslands to the south and southwest, an area now known as the Sahel. Herding dramatically reduced the risk of hunger because the mobile food supply could be relocated to take advantage of local differences in forage and water availability.15 Human populations came to depend on cattle for the milk and meat their animals produced. The Sahara’s earliest food-producing communities thus were organized around the practice of herding.

Animal husbandry did not stop with the taming of wild cattle. Ancient herders continued the process of selecting and breeding animals with desirable traits. One breed with long bulbous horns, known as Kuri or Buduma cattle, developed around Lake Chad. It consumes aquatic plants for food and spends several hours each day immersed in water. The breed’s long horns act as a flotation device. Herders developed another indigenous breed in the humid woodlands of Guinea’s Futa Jallon plateau: the dwarf humpless cattle known as n’dama, whose outstanding virtue is resistance to the bovine sleeping sickness (trypanosomiasis) transmitted by the tsetse fly. The n’dama breed allows cattle-keeping in fly-infested areas that would prove lethal to animals without this special trait.16 Ancient herders bred other types for aesthetic features. The continent’s indigenous breeds are distinguished by slender, sinewy limbs and often by their horns, which are long, inward curving, and crescent- or lyre-shaped (figures 1.2, 1.3).17

FIGURE 1.2. Indigenous African n’dama cattle, northern Sierra Leone, 1967. Photo courtesy of David P. Gamble.

Cattle were not the only animals that ancient Africans domesticated in arid environments. Between 7,000 and 5,000 B.P. Africans developed the donkey (Equus asinus) as a transport animal. The animal enabled early pastoralists to respond to growing aridity through frequent relocations between camps and oases. The donkey’s capacity to carry wood, water, and people over short distances, made it an efficient transportation system. It was likely domesticated from the indigenous wild ass (E. africanus), which occupied the savanna steppes that then stretched from the Horn of Africa westward to the Atlas Mountains (now part of the Sahara).18 Eventually, the donkey spread from the African continent to the Near East and Mediterranean world. Another savanna food animal that Africans domesticated was the guinea fowl (Numida meleagris), the continent’s indigenous poultry species.19

The experimental process that led Africans to domesticate cattle and develop breeds adapted to specific ecological and aesthetic contexts was applied to other livestock introduced to the continent. Sheep and goats arrived in the Saharan regions by 8,500 years ago, camels in the first millennium B.C.E., and the humpless Indian zebu cattle about 2,000 years B.P. Each of these domesticated species enabled African pastoralists to diversify their herd composition and breeding stock. With drought a recurrent threat in these regions, ownership of many different types of livestock reduced the chances of losing everything, diffusing the risk among different breeds and species. Herd diversification moreover improved the forage efficiency of savannas because each species grazed different parts of grasses or consumed plants unpalatable to the others. The introduction of these food animals involved African herders in a continuous process of experimentation as they adapted the species to their needs. They crossed the indigenous long-horn cattle with the zebu to develop a hardy drought-tolerant breed known today in Uganda as ankole. Herders also bred a type of woolless thin-tailed sheep that was particularly adapted to the continent’s hot arid savannas but that was also able to survive in humid tropical areas. This so-called hair sheep was raised for meat rather than fiber. A distinct fat-tailed and also nonwoolly sheep, adapted to a variety of savanna and mountain environments, became the predominant breed across the eastern side of the continent.20

FIGURE 1.3. Indigenous African n’dama cattle, the Gambia, 1963. Photo courtesy of David P. Gamble.

As livestock keeping spread throughout the sub-Saharan region, so did the indigenous grasses that provided forage. African pasture grasses are adapted to tropical growing conditions. Some flourish in well-drained soils, others in humid bottomlands, still others in sandy soils of arid landscapes. When the Portuguese and Spanish arrived along the western coast of Africa in the fifteenth century, these native forage and fodder grasses facilitated animal husbandry in many diverse tropical settings. Spurred by the needs of burgeoning colonial enterprises, European ships carried the continent’s food animals and pasture grasses as live provision and breeding stock to the New World tropics.

Domestication is the selection process by which human populations adapt plants and animals to their need for a predictable food supply. It is a symbiotic relationship, as domestication allows species to spread beyond their original geographical boundaries in exchange for their use as food by their benefactors. Plant and animal domestication began after the last ice age and developed independently in several world regions, including Africa. Linguistic and archaeological evidence suggests that people in two parts of Africa—the West African savannas and the southern eastern Sahara—began cultivating plants as early or nearly as early as people in southern East Asia, northern China, the Near East, interior New Guinea, and Mesoamerica. However, ancient Africans for a long time allowed their cultivated crops to interbreed with the wild forms, thus slowing the appearance of fully domesticated varieties. The presence of tropical African domesticates such as melons (already in Egypt by the third millennium B.C.E.) and finger millet and pearl millet (in India by the second millennium B.C.E.) requires, in any case, that African agriculture developed well before these dates.

The process of agricultural domestication in Africa, as elsewhere, involved the selection of wild plants that displayed fundamental features esteemed by human populations. These traits included larger size, higher yield, controlled ripening, palatability, and ease of processing. Importantly, the morphological changes that accompanied the transformation of a wild plant to its domesticated progeny took a very long time to accomplish. Domestication was a slow and laborious process, one that may have in the African case taken two or three millennia to realize.21 A Saharan rock painting, dating to circa 4000–1500 B.C.E. (plate 1), depicts women apparently gathering grain. Considering the extremely arid conditions that prevailed in the Sahara by that period, they may be collecting wild grain that sprouted after a rare rain, since farming by then would have been risky if not impossible.

Current evidence from archaeology, historical linguistics, and botany suggests that plant domestication was initiated in Africa during the millennia before 4,000 B.P. Just how long before is an issue still to be resolved. In northeastern Africa, archaeological research suggests that the cultivation of sorghum was underway in Sudan by 7,000–6,000 B.P.22 There is also indirect evidence for the domestication of cotton by 5000 B.C.E., with spindle whorls recovered from archaeological sites near Khartoum.23 Indirect evidence of African plant domestication has been found in the archaeological record of the West African rainforest. The spread of polished stone axes through the rainforest, as tools for clearing the forest for the cultivation of yams, dates to 5000–4000 B.C.E.24 Linguistic evidence from both regions implies that food plants were cultivated as much as 2,000 years before these indirect archaeological indicators. But we still lack in most areas sufficient archaeological research to substantiate the cultivation of plants before 5000 B.C.E. The cumulative weight of this evidence from archaeobotany and linguistics nonetheless suggests the likelihood that plant cultivation is far more ancient on the African continent than has been supposed.25

In Africa, as elsewhere, agricultural domestication resulted from experimentation with wild plants that people had gathered for millennia. All the foodstaples of the world are based on the achievements of our collective forebears, who identified in widely divergent environmental settings edible foods and plants with desirable properties. In Africa, ancient plant gatherers initiated the domestication process with the wild grasses, fruits, nuts, greens, legumes, and underground tubers that they had long collected for food. From this botanical assemblage, they created the plants’ domesticated progeny. Despite the turn toward agriculture, the foraging of wild botanical resources continues to provide contemporary populations important supplemental sources of food and medicine, especially in areas of unpredictable rainfall. On the savannas of West Africa alone, more than two hundred plants are still foraged for their edible fruits, seeds, and leaves.26

Most of the plants ancient Africans domesticated are adapted to a wide range of tropical farming conditions. Several are drought-tolerant; others mature rapidly or possess specific traits that promote food production in diverse ecological settings. Pearl millet, for example, produces a harvest in just a few months; sorghum grows more slowly and is able to mature in the dry season, relying on the residual moisture held by the soil. Although the yam is considered a tropical forest crop, it originated on the western savannas of the continent. Thought to be one of the first food crops Africans domesticated, the yam was subsequently developed as an important tuber of the humid tropical forests of Nigeria and Cameroon.27

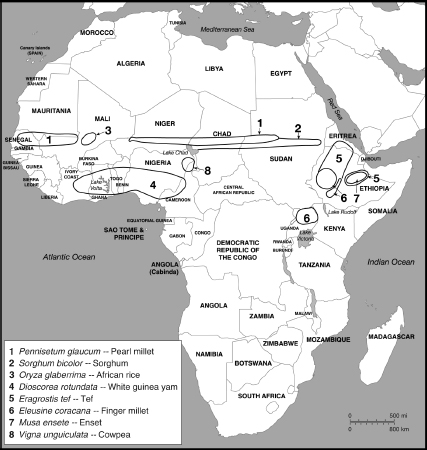

Ancient Africans fully met the challenges of a dramatically changing Holocene landscape by adapting their subsistence strategies. Agricultural origins in Africa took place in lowlands and hilly regions, in various types of grasslands, wetlands, and forests, and under a variety of ecological conditions. On the African savannas, plant domestication occurred over a broad region rather than in a specific geographic center of diversity. This noncentric pattern of domestication contrasts with most other regions of Africa and the world, where agriculture spread from a single geographic locus. Figure 1.4 depicts the geographical contours of these patterns of African plant domestication for some of the continent’s principal foodstaples.28

FIGURE 1.4. Areas of domestication of selected African crops.

SOURCE: Adapted from Harlan, “Agricultural Origins,” 471.

Agricultural domestication was a dynamic and variegated process. Ancient Africans developed different subspecies of each domesticate for specific ecological conditions and human needs. Sorghum, perhaps the most ancient of African cereals, is particularly illustrative: from its wild origins in the African savanna, there developed more than two dozen cultivated species. Some are drought-tolerant, others are adapted to river floodplains, where they are planted in soils exposed during the seasonal retreat of flood waters. Sorghum’s environmental versatility is matched by its many uses. Some types yield a sweet, molasses-like syrup; the grain may be malted to brew beer, and the whole plant makes excellent livestock silage.29 Pearl millet—the most drought-tolerant of all cereals—reflects a similar adaptability to environmental and human needs. African farmers developed types that enabled food production right to the edge of the Sahara Desert. Such adaptations contributed to shaping the noncentric pattern that distinguishes African agricultural beginnings in the savannas.

As the Holocene climate changed, farming gave African peoples a second way to improve food security. Agriculture contributed a crucial livelihood strategy to the diversified systems of food procurement that human populations increasingly demanded. By supporting a range of food-procurement strategies—hunting-gathering, herding, fishing, and farming—the savannas enabled the development of specialist ethnic groups.30 The wide variance in rainfall between and within years made such adaptations, and the food exchanges they facilitated, vital to the collective survival of the continent’s peoples. Plant domestication added yet another crucial component to the indigenous knowledge systems that had developed on the continent. Thousands of years later, these African faunal and botanical species would play a role in the history of Atlantic slavery.

Plant domestication in Africa represents a significant contribution to world agriculture. Africans added three important cereals, a half-dozen root crops, five oil-producing plants, more than a dozen leafy vegetables and greens, about a half-dozen forage crops, a variety of beans, nuts, and fruits, in addition to the versatile gourd (used as a container, for musical instruments, and fishing floats).31 Many of these crops are today vital to the sustenance of millions living in tropical areas around the world.

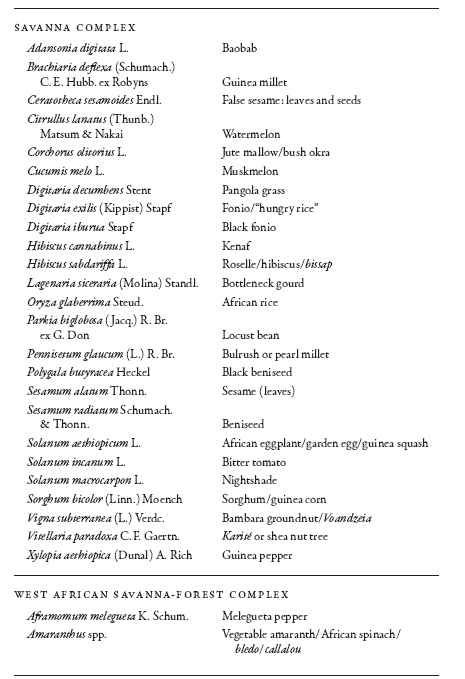

Agricultural domestication occurred in three distinct ecological complexes of sub-Saharan Africa: the highland to lowland gradient of Ethiopia; along the savannas that stretch nearly unbroken across the continent from Sudan to Mauritania; and the forest-savanna ecotone of present-day Cameroon and Nigeria in west-central Africa. Figure 1.5 lists the principal African food domesticates from each of these distinctive environmental settings.

Plant domestication unfolded in the highlands of Ethiopia and Uganda and in the southern Ethiopian lowlands. Ethiopia is the birthplace of the world’s premier coffee (Coffea arabica). Other important food crops domesticated in the region include finger millet (Eleusine coracana), tef (the cereal staple of Ethiopian cuisine), the lesser-known enset (a root crop that resembles the banana), the lablab or hyacinth bean (also known as bonavist), and the castor bean oil plant.32 Finger millet, the lablab bean, and the castor plant diffused widely across Africa and the ancient world. Castor bean was esteemed for its dual use as a lamp oil and medicinal.33

The savannas north of the equator hosted the domestication of many African foodstaples that have become significant outside the continent. This ecological region, of such significance in the story of African cattle domestication and the ancient migration of pastoralists from the eastern Sahara, is central to the development of many of the world’s most important tropical cereal and pasture grasses. Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), for example, today ranks fifth in world cereal grain production. It produces a larger grain than pearl millet. The sorghum plant physically resembles maize in its vegetative stage, but instead of producing an ear its stalks are crowned by a plumed head of seed grains. It is typically made into porridges of varying thickness and brewed into beer.

The archaeobotanical evidence sets the domestication stage in the history of pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) cultivation no later than 3,500 years ago.34 Thriving in arid climates where no other cereal grows, the plant produces exposed grains along a stalk that resembles a bulrush or cattail. Pearl millet is the most drought-resistant of the world’s principal food grains; no other cereal produces such reliable yields under such challenging conditions of withering heat and minimal rainfall. For precisely these reasons, it is the dietary staple of millions living in arid tropical regions. In Africa the cereal’s grains are ground as flour or cooked as a whole grain. Pearl millet is prepared in a variety of ways, as unleavened bread, porridge, fermented snacks, and steam-cooked couscous. In the mountainous interior of Niger, pastoralists long ago learned to prepare it for desert journeys without the need for additional cooking. The grain is roasted and mixed with dried dates and goat cheese. The millet-based mixture provides a nutritious dietary staple on long caravans across the Sahara and obviates the need to carry firewood and water for meal preparation.35

An even smaller grained type of millet is fonio (Digitaria exilis, D. iburua), or “hungry rice.”36 More drought-tolerant than pearl millet, this African grain thrives on poor savanna soils. It was of such importance in Sahelian food systems that Ibn Batt ta described it on his visit from southern Morocco to Mali in 1352, where it was made into couscous. While fonio can be harvested in just six to eight weeks, its very small grains make removal of the husk quite difficult, which has limited the adoption of this otherwise nutritious grain outside Africa.37

ta described it on his visit from southern Morocco to Mali in 1352, where it was made into couscous. While fonio can be harvested in just six to eight weeks, its very small grains make removal of the husk quite difficult, which has limited the adoption of this otherwise nutritious grain outside Africa.37

FIGURE 1.5. Food crops of African origin.

SOURCES: Harlan, Crops and Man, 71–72; MacNeish, Origins of Agriculture, 298–318; Vaughan and Geissler, New Oxford Book of Food Plants, 10, 26, 38, 128, 174; Marshall and Hildebrand, “Cattle before Crops,” 123–24; Tropicos, www.tropicos.org; Aluka, www.aluka.org.

Another significant cereal domesticated in the savanna landscape of West Africa is African rice (Oryza glaberrima). It is distinguished by a reddish hull that encloses the grain. The domestication of rice took place later in Africa than in Asia, but it unequivocally occurred in West Africa prior to the introduction of Asian rice (O. sativa) to the African continent. African rice was present at the beginning of human occupation at Jenné Jeno along the interior delta of the Niger River in Mali some two thousand years ago.38 Archaeobotanical data from this and other sites in the region increasingly support a date no later than 3,500 B.P. for the domestication of African rice.39 The linguistic evidence suggests that the cultivation of this crop began even earlier, as much as 5,000 years ago.40 Secondary centers of rice domestication are believed to have developed north and south of the Gambia River and in the Guinean Highlands. This has contributed to the broad extension of West Africa’s indigenous rice region southward from the Senegal River to the Ivory Coast and inland all the way to Lake Chad.41

The harsh environment of the drier African savannas supported the ancient domestication of the African eggplant (Solanum aethiopicum), prized for its fruit and leaves.42 The region is also home to several cucurbits—plants that include melons, gourds, squashes, and cucumbers. Many of these species were esteemed in ancient times not so much for their fruit, but for their edible roasted seeds. They remain important as thickeners and flavoring agents in many West African dishes, where they are known collectively as egusi melons.43 Africa is the continent where the ancestor of the watermelon was domesticated. Its prototype was originally a bitter melon that was grown on arid savannas for its edible seeds and as a storable form of moisture.44 Africa is also believed to be the original home of the cantaloupe or muskmelon (Cucumis melo). The bottleneck gourd (Lagenaria siceraria), another cucurbit species considered of African origin, has been known since ancient times for its edible seeds, utility as a container and ladle, and use as a percussive or stringed musical instrument. The gourd’s fundamental cultural importance is likely the reason it often serves as a symbol and metaphor in oral and written traditions. As the chapter’s epigraph indicates, the gourd is the vessel of wisdom in many African legends. In plantation societies of the American South, the African gourd symbolized freedom, as in the African American song, “Follow the Drinking Gourd”—in reference to the celestial Big Dipper, whose stars guided passengers of the Underground Railroad to the north and freedom.45

Africa hosts wild and semicultivated species of sesame, which are grown for their leaves as much as their seeds. The sesame crop of international commerce (Sesamum indicum) was domesticated several millennia ago on the Indian subcontinent.46 Africans domesticated the protein-rich Bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea), which grows underground like peanuts and is of exceptional nutritional quality. Another savanna plant widely known beyond Africa is hibiscus (Hibiscus sabdariffa). It produces a refreshing beverage with a cranberry-like flavor and color. Known as bissap in Senegal, where it is the national drink, throughout Latin America it is called flor de Jamaica. Hibiscus is an important ingredient of many commercial drinks and herbal teas. Finally, the savanna hosted the domestication of the most important medicinal plant found in African-descended regions of the Americas, the bitter melon (Momordica charantia). Sometimes referred to as Chinese bitter melon, the African plant’s medicinal values since ancient times have also been appreciated in Asia for a wide variety of cures.47

The African savanna supports a variety of trees that since antiquity have provided humans with useful by-products. Farmers have long protected these species as sources of food, oil, resins, cordage, and medicines. Chief among these savanna species are the locust bean (Parkia biglobosa), baobab (Adansonia digitata), gum arabic (Acacia senegal, A. seyal), and the shea nut tree (Vitellaria paradoxa). Gum arabic, today important as a food stabilizer and an ingredient of most of the world’s soft drinks, was among the first African food products known in medieval Europe.48 It was used as a medicinal and as a component of inks and paints. The shea nut tree has provided a cooking oil and moisturizer to savanna populations for at least a thousand years. Today it is promoted by the global cosmetics industry in natural skin care products.

The grassland steppes—so central to the story of African cattle and the ancient pastoralists who tended them—are the original home of many of the world’s most important tropical pasture grasses. These include several with suggestive common names: Angola or Pará grass (Brachiaria mutica), guinea grass (Panicum maximum), Bermuda grass (Cynodon dactylon), molasses grass (Melinis minutiflora), and thatching grass (Hyparrhenia rufa). Besides their use as fodder, several of these grasses have applications in traditional medicines.49

The savanna-to-forest transitional zone found in Cameroon and Nigeria provided the third crucial setting for the domestication of African plants. Located between the southernmost extension of cattle ranching and evergreen forest, this ecologically diverse woodland savanna is believed to support the richest diversity of flora and avian species on the continent. The West African agricultural tradition likely began with the yam, where natural clearings allowed the plant to thrive. Among this region’s indigenous plants are many that provide dietary protein, such as the cowpea, pigeon pea, and one lesser-known legume—Hausa, or Kersting’s groundnut, grown for its edible underground nut.50 In Africa, these nutritive plants provide food for both people and animals. The cowpea is a cousin of the “Asian” long bean, which is an important ingredient in Far Eastern cuisine.51 Known in North America as the black-eyed pea, the cowpea is frequently intercropped with sorghum. Sorghum’s tolerance of infertile soils perfectly complements cultivation of this legume, whose nitrogen-fixing properties restore depleted nutrients.

The forest-savanna ecotone harbored other plants that have figured prominently in food traditions outside the continent. These include okra, the tamarind, the oil palm (the signature ingredient of Brazilian Bahian cooking and used also to make Palmolive soap), and the yellow yam (Dioscorea cayenensis). Initially domesticating them from a wild savanna species, African farmers developed several cultivars of yam (D. cayenensis, D. rotundata, D. dumetorum, D. bulbifera) for cultivation in the wet tropics. Planted in aerated earthen mounds, the yam produces with little effort large tubers that can be stored for later consumption. It has long served as a principal dietary staple of humid tropical Africa. The tuber is also widely recognized for its medicinal properties. Its leaves are chewed to relieve gastric distress; the root provides steroids with anti-inflammatory properties that reduce cholesterol levels, swelling from arthritis and rheumatism, and fungal growth on human skin. Its value as a food crop and medicinal has long been vested with symbolic meaning through celebrations known as yam harvest festivals. Europeans first encountered the yam in West Africa.52

Many important stimulants, medicinals, and spices also originated in the deciduous and evergreen forests of western Africa. These include several plants whose African origin is seldom recognized. Two of the most widely consumed beverages in the world today are based wholly, or in part, on plants ancient Africans domesticated: the kola nut (a principal ingredient of Coca-Cola) and coffee. Other plants of African origin include melegueta pepper and the ackee apple, which along with salt fish is the national dish of Jamaica.53

The cultivation of food in the wet tropics relies upon markedly different principles than that of temperate farming systems. What appears as luxuriant natural vegetation often masks soils of limited fertility. Most tropical plant nutrients are instead locked up in the vegetative mantle. Once an area is cleared for agriculture, soil fertility undergoes rapid decline. In the era prior to chemical fertilizers, fertility was restored by burning secondary growth for ash, adding organic matter such as animal manure and crop residues, planting beans and leguminous trees that make atmospheric nitrogen available to crops, and by leaving the land periodically fallow. The high year-round temperatures of the tropics moreover contribute to the proliferation of insect pests. Farmers do not benefit from the seasonal climate swings of temperate zones, where colder weather reduces insect numbers. Heavy tropical rainfall threatens the erosion of valuable nutrients when soils are cleared for agriculture. Considerable care must be taken to prevent the percolation of valuable plant nutrients down the soil horizon, which would put them beyond the reach of crop roots.

To minimize these agricultural constraints, farmers across the Old and New World tropics domesticated a diverse array of plants to realize their food needs. Over millennia of trial and error, they devised ingenious ways to feed themselves without destroying the soil that supports crop growth. Then, as now, they often planted in multicropping systems—different species and cultivars grown together on the same plot—intercropping the cultivation of seed plants, tubers, and legumes with valuable fruit-, nut-, and oil-bearing trees. This crop diversity diminishes the ability of insects to destroy an entire food system. It encourages a multistoried agricultural plot, mimicking naturally tiered tropical canopies and ground covers. Erosion from tropical downpours is thus minimized. In reproducing the species diversity of the original forest cover, this farming method transforms a rainforest into a food forest.

In the semiarid tropical regions of Africa, the sharp demarcation between wet and dry seasons promoted the domestication of suitable crops and the development of new farming strategies. Pearl millet and sorghum were revolutionary crops, perfectly adapted to the wide seasonal swings of temperature and moisture. Paramount among agricultural practices was the combination of these drought-tolerant cereals with nitrogen-fixing legumes to provide a full complement of protein. Food availability in semiarid Africa was moreover enhanced by flexible land-use practices that encouraged different ethnic specialist groups to cooperate for mutual benefit. In areas that would support agriculture, farm plots were turned over to herders at the end of the wet-season harvest. The livestock would occupy the farmland as pasture; as the animals grazed the cereal stubble, they deposited manure, a process that continuously renewed soil fertility and so prepared the plot for its return to cultivation. This complementary land-use system contributed to the diverse food landscapes that Africans developed over millennia in a tropical continent not especially favored with fertile soils.

With such techniques, African farmers transformed tropical environments into harvestable food plots. The agricultural principles used to accomplish this are not self-evident or easily acquired. They are inherited as cultural funds of knowledge. The legacy of African domestication is most clearly seen in tropical landscapes, with influences that would traverse oceans and continents.