n (d. 1038) illustrates a field of sorghum (figure 2.1).

n (d. 1038) illustrates a field of sorghum (figure 2.1).Sankofa is the mythic bird that flies forward while looking backward. The egg it holds in its beak symbolizes the future. Sankofa’s flight reminds us to look to the past in order to move forward to the future.

Unumbotte then gave sorghum to Man, also yams and millet. And the people gathered in eating groups that would always eat from the same bowl, never the bowls of the other groups. It was from this that differences in language arose.

THE CONTINENT OF AFRICA WAS anything but peripheral to the vast trading networks that connected peoples of the ancient world across land and sea. Africa intersected the maritime routes that initially linked Asia to the Mediterranean. Plants and animals that came out of Africa through these routes are rarely appreciated as African domesticates. The donkey, for instance, became the dominant beast of burden throughout much of the Old World. It appears throughout the Old and New Testaments and is depicted in Egyptian hieroglyphs. When Carthaginian Hannibal crossed the Italian Alps during his campaign against Rome, he did so with African forest elephants (a species smaller than its savanna cousin, now extinct in its former North African range).1 There was even a demand for the continent’s wild animals, which were frequently cast in Roman combat spectacles. Africa’s participation in intercontinental trade networks grew during the Middle Ages, when Africa supplied ivory (for musical instruments and board games), gum arabic as a medicinal, melegueta pepper (or “grains of paradise”) for seasoning dishes, and gold for coinage. But food too was a part of the ancient trade in commodities. Thousands of years ago, African food crops journeyed beyond the areas of their domestication. Sorghum, pearl and finger millet, and several legumes were introduced to other parts of the Old World. There the African crops revolutionized food availability in semiarid landscapes.

Although the Columbian Exchange begins its historical timeline with the fifteenth-century maritime expansion of Iberians, significant botanical transfers also occurred in the pre-Columbian period. Notable are the Asian crops that diffused with the expansion of Islam in the seventh century, particularly sugarcane. Plants were also transported through ancient Indian and Pacific ocean networks, whose seafarers possibly connected Asia and Oceania with the Pacific coast of the Americas.2

Botanical texts strive to determine the geographical areas where crops originated. Scholarship on transoceanic and intercontinental crop exchanges attempts to shift the focus by identifying the plants that accompanied human beings across oceans and lands. However, neither perspective places subsistence, and the trading systems supported by subsistence, at the center of concern. Over the millennia preceding the first visits to Africa of Portuguese mariners in the fifteenth century, African crops journeyed to Asia. Africans additionally made important contributions to the development of several introduced Asian food plants in the same time period. Thus begins the botanical legacy of a continent.

African botanical exchanges with the ancient world are evident in the archaeological and historical record in three distinct eras. They begin three to four thousand years ago through Indian Ocean trading routes to India and beyond. We see them next in the florescence of a desert agricultural kingdom in southern Libya in the first millennium B.C.E., which linked sub-Saharan Africa to the Mediterranean. They are additionally evident with Muslim expansion from North Africa to the Iberian Peninsula from the eighth century.

Greek historian Herodotus (ca. 484–425 B.C.E.) wrote of Africa as an inhospitable place, the hottest part of the known world, at a time when the Garamantian kingdom in southern Libya was developing new agricultural practices to cope with increasing aridity.3 The Garamantes were descendants of Berber and Saharan pastoralists, who since ancient times had moved herds of cattle, sheep, and goats across Saharan grasslands. They settled in southern Libya in a region of lakes and springs, where by the beginning of the first millennium B.C.E. they had sedentarized and begun the cultivation of crops. Herodotus viewed the Garamantes as barbarians who dwelled at the periphery of the civilized world; nevertheless, their settlements lay astride the crucial caravan routes that connected the Mediterranean world to sub-Saharan Africa (especially to Gao on the Inland Delta of the Niger River) and the Nile Valley to the east. Between the first millennium B.C.E. and 500 C.E., the Garamantes became a dominant power in the central Sahara, in part because of the trade in salt, slaves, and wild animals to Rome, but also because of an agricultural system that supported settlement in a region that was experiencing rapid desertification. Recent archaeological research has improved our understanding of the methods the Garamantes used to make the desert bloom and of the role of African domesticates in the region’s specialized agricultural system. As a consequence, the traditional view of the Garamantes as a desert outpost of Mediterranean food systems is changing to one whose success was also crucially linked to the achievements of farming peoples living in the savannas south of the kingdom.4

The Garamantes began the shift to agriculture with a crop repertoire initially inherited from the Mediterranean. They planted emmer wheat, barley, dates, grapes, and figs as foodstaples. But by the first millennium B.C.E., the region’s remaining lakes and springs had disappeared. However, the rainwater that once sustained the Garamantes did not entirely vanish. Significant deposits survived underground, with an enormous lake of subterranean water lying beneath the Garamantian heartland. This fossil water had accumulated during a series of wet climatic cycles that came to an end around 3500 B.C.E., when the Sahara shifted to a permanently drier climate. In response to the continuing desertification, the Garamantes began developing a water-extraction system (called foggaras) that took water from the vast underground aquifer.5

In the middle of the first millennium B.C.E., the Garamantes made the desert bloom by adopting the foggara technology that the Persians had previously introduced to Egypt. It involved digging vertical shafts to reach the aquifer and channeling the subterranean water flow to a downstream location where it could be captured for irrigation. A prodigious amount of human labor was involved in the construction and maintenance of the irrigation infrastructure. The access shafts were dug some 30 feet apart to reach the water, which was located 30–130 feet below the surface. Eventually 500 miles of underground channels were dug. This water-extraction network supported the food system that made the Garamantes a dominant power over 70,000 square miles of desert in the central Sahara. The cultivated fields irrigated with fossil water enabled the kingdom to achieve a population concentration of perhaps as many as ten thousand people. In the Sahara Desert an urban society had developed on top of the subterranean water that flowed beneath it.6

The Garamantes accomplished this feat through slavery, principally with peoples drawn from the dense farming populations south of the Sahara. Initially salt was traded for slaves, but as the Garamantes grew increasingly reliant upon the water-extraction system for their subsistence, they turned to slave raiding to supply the necessary labor force for its maintenance and expansion. Their slaving expeditions, which reached all the way south to the shores of Lake Chad, netted captives from agricultural societies. The presence of sub-Saharan farmers in the Garamantian kingdom coincides with the introduction of two important crops to the foggara food-production system—drought-tolerant sorghum and pearl millet, both originally domesticated in the Sahel. The indigenous African cereals are evident in the archaeobotanical record of the Garamantes during the fourth century B.C.E., at a time when the expansion of the irrigation system was underway. Sorghum and millet contributed considerably to overall food supplies because, in contrast to winter-grown Mediterranean cereals, the African domesticates thrive in the hotter summer months. In enabling a second cycle of agricultural production within the calendar year, the African domesticates made a substantial contribution to the kingdom’s cereal reserves. An additional food harvest during the summer would have been critical to subsistence availability at the peak of foggara development between the first and fourth centuries C.E., when the estimated workforce likely numbered one to two thousand slaves. The Garamantes’ revolution in food production thus was influenced by the arrival of farming peoples from the Sahel, who were enslaved to build and service the irrigation system, but for whom sorghum and millet were traditional dietary staples.7

By the fourth century C.E., when slaves formed perhaps as much as 10 percent of the population, the groundwater table that sustained the Garamantes began an irreversible decline. Excavation to reach the aquifer grew more difficult and labor demanding. The fossil reserves proved finite, and around 500 C.E. the kingdom collapsed. The population dispersed to desert oases and mountainous areas with stream flow and there practiced irrigated farming on a smaller scale. Sorghum remained an important crop to their “Berber” mixed-race descendants, as it fed both herders and their livestock.8

African crops infiltrated the food systems that accompanied the expansion of Islam from the seventh century. Muslim trading networks moved Asian rice, citrus, and sugarcane from India to the Middle East, the Mediterranean, Egypt, and East Africa. But they also transported sorghum, pearl millet, and other plants from the African continent to geographical areas within the burgeoning caliphate.

One of the earliest historical references to cultivation of African cereals in the Muslim world comes from Mesopotamia, where slave-based sugar plantations developed near the caliphate stronghold of Basra in the south of Iraq. Cultivation of these marshlands for sugarcane and other crops required extensive reclamation of soils, an arduous task. Africans, mostly taken from East Africa (known in ancient times as Zanj), comprised a considerable segment of the tens of thousands enslaved to carry out the work. Slaves were made to remove by hand the salt crust, or natron, from the topsoil in order to expose the fertile soil beneath it. Many African domesticates were cultivated for food, including sorghum, millet, and melons.9

In a prelude to the conditions that prevailed on sugar plantations in tropical America, Basra’s slaves toiled under wretched conditions. Inadequately nourished and unable to improve their social conditions, the Mesopotamian Zanj led two ninth-century slave uprisings. In the major rebellion of 868–69 C.E., they captured Basra and other towns, built their own capital city, and achieved fourteen years of freedom before their defeat and reenslavement in 883 C.E.10

The rise and expansion of Islam facilitated the geographical dispersal of several other crops of sub-Saharan origin to the Middle East and Europe. Coffee (the esteemed arabica type), which originated in Ethiopia, was already a feature of daily life in the Arabian Peninsula and Middle East before the Dutch popularized the beverage in Europe during the seventeenth century. The expansion of Islam across North Africa, along trans-Saharan caravan routes and southward to African savanna societies, invigorated ancient long-distance trade networks with the Mediterranean. It contributed to the northward diffusion of the West African kola nut, a stimulant even richer in caffeine than coffee, and the appearance of melegueta pepper and gum arabic in medieval European markets.11

African sorghum transformed food production in Muslim Spain. Repeated migrations of Berbers from Morocco to al-Andalus between the eighth and eleventh centuries led to its diffusion to the Muslim-held Iberian Peninsula.12 Sorghum was ideally adapted to Berber agropastoral practices, as it doubled as a food and feed crop.13 The drought-tolerant grain produced a second harvest in the Mediterranean climate during the hot and dry summer and became the dietary staple of the lower classes of Islamic Spain. It was prepared in a thick porridge resembling polenta in consistency and use. Sorghum so changed subsistence patterns that Ibn Khaldun, who lived in fourteenth-century Seville, attributed the good health of the population to its “diet of sorghum and olive oil.”14 A Latin copy of an eleventh-century medical text by Ibn Butl n (d. 1038) illustrates a field of sorghum (figure 2.1).

n (d. 1038) illustrates a field of sorghum (figure 2.1).

FIGURE 2.1. Illustration of sorghum, eleventh-century Spain, by Baghdad physician Ibn Butl n (d. 1038), from Latin translation of his treatise Tacuinum sanitatis, printed late fourteenth century in Italy.

n (d. 1038), from Latin translation of his treatise Tacuinum sanitatis, printed late fourteenth century in Italy.

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission of Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Ser. Nov. 2644, fol. 48v.

The African millets are evident in South Asia at a much earlier date. They found a particular niche in the agricultural systems of the arid and semiarid tropics, where they provided an adaptive cereal. The archaeological record from western India indicates the presence of sorghum and millet between 2000 and 1200 B.C.E. Finger millet, cowpea (also valued as cattle feed), and the lablab or hyacinth bean reached South Asia during the second millennium B.C.E.; the tamarind, pigeon pea, okra, and the castor bean followed.15

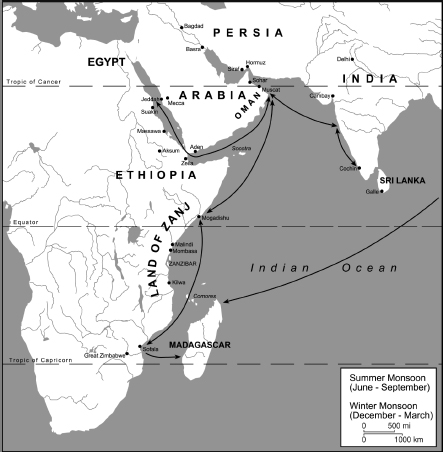

FIGURE 2.2. Monsoon Exchange, 2000 B.C.E.–500 C.E.

The seeds of the African food plants made their way past the Arabian Peninsula to the Indian subcontinent along two principal trade routes: one that linked the Ethiopian Highlands to the Horn of Africa; the other connecting the East African highlands to Zanj (“Land of the Blacks,” now known as the Swahili Coast) (figure 2.2). The coastal ports formed the African legs of a maritime trading network that spanned the Indian Ocean. Recovered artifacts suggest that East Africa and Asia were trading as early as 3000 B.C.E.16 The interconnected bodies of water were known as the Erythraean Sea. The navigation route from Roman Egyptian ports and the trading opportunities found along the way are described in the navigational guide, the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, written in the first century C.E. The patterns of the seasonal winds enabled ancient mariners to sail across the Indian Ocean. Between December and March, the monsoon blows from the northeast, which permits downwind voyages westward to the Red Sea. The reversal of wind direction between June and September facilitated maritime crossings to India. By sailing the monsoon winds, mariners could complete the circumnavigation of the Erythraean Sea in just one year.

Recognizing the significance of the wind-assisted trade networks across the Old World tropics for the plant transfers that occurred between Africa and India between the second millennium B.C.E. to first millennium C.E., historian J.R. McNeill terms this period of ancient crop movements the Monsoon Exchange.17 Notable among the Asian plants brought to Africa by the Monsoon Exchange are two tropical root crops, taro (known also as cocoyam) and the banana. Both are of Southeast Asian origin. They became important foodstaples of the African humid tropics over the same period that sorghum, millet, the Vigna species of legumes, and watermelon journeyed eastward to semiarid India.

Botanical studies place domestication of the banana’s wild progenitors in Southeast Asia, although a second center is suggested by the presence of edible cultivated bananas in New Guinea possibly seven thousand years ago. Wild bananas contain many seeds and little comestible pulp. Domestication to a more edible fruit increased the ratio of pulp to seed, a process that eventually left the plant entirely seedless. But selection for the seedless trait meant that the banana was no longer able to reproduce by natural means. It could only be propagated by the removal and replanting of vegetative cuttings of the offshoots (or suckers) that develop from the underground stem (or corm) of the mature plant. Domesticated bananas thus depend upon people for reproduction. Human agency was moreover necessary for the plant’s dispersal throughout Asia and beyond.18

The banana arrived in Africa through the maritime networks of the Monsoon Exchange. It accompanied seafarers from Asia across the Indian Ocean to the African continent. The plant’s value to ancient navigators was not as we might suppose, for its fruit, but rather its underground starchy stem, which is also edible and remains so for long periods—the perfect victual for extended voyages at sea. Furthermore, cuttings of the stem stored for several months will not lose the capacity to develop into normal plants if they are later replanted. There is little doubt that Musa root stems, with their long-term regenerative capability, were introduced to Africa through westward monsoon voyages.19

The term “banana” actually refers to two closely related edible plants of the Musa genus, the banana and plantain.20 While the Western world categorizes the two by calling the sweet “ready to eat” fruit the banana and the starchy cooking species the plantain, this distinction is not observed in many tropical societies, where cultivars of both types are cooked. Africans prepare plantains and bananas in a variety of ways. They boil, steam, poach, bake, and pound the starchy staple as an accompaniment to meat and vegetable stews. Some cultivars are eaten as fruit; others are brewed into beer. The plant’s leaves are used for wrapping food; its underground rootstocks are edible and provide animal fodder. The practice of eating the stem is observed in equatorial Africa, where it is sometimes consumed as a famine food.21

In Africa, plantains are generally grown in lowland equatorial forests, bananas at higher tropical altitudes.22 The geographical focus for plantain cultivation centered on the rainforests of West and Central Africa (from southern Cameroon south and east through the tropical rainforest), whereas bananas came to dominate the East African highlands or Great Lakes area of East Africa. Linguistic evidence for Musa cultivation in Africa dates to the first millennium C.E., when the plant entered the continent by way of East Africa.

Despite the proximity of East Africa to the ports of the Monsoon Exchange, early evidence for Musa in Africa comes from an archaeological site in southern Cameroon. Although there is still debate about whether the plant remains are in fact Musa, the phytoliths recovered from the bottom of ancient refuse pits have been dated between 840 and 370 B.C.E.23 If correct, this would date the Asian plant’s cultivation by Africans on the western side of the continent to the last millennium B.C.E.24

The remarkable advantages of the Musa plant attest to its ready adoption by African farmers as a foodstaple. It is among the highest-yielding crops, and the labor inputs are minimal. In contrast to cereals, bananas and plantains can be harvested throughout the year, thus providing dependent populations a constant and reliable food source. Yields of the plant are extraordinary: over 200,000 pounds can be taken from a single acre. This figure is ten times the yield of yams and one hundred times that of potatoes grown on an equivalent amount of land. An established banana garden will produce for thirty or more years, nearly the entire working life of an average African farmer.25

The importance of the banana to Africans is reflected in the profusion of cultivars developed on the continent. Experimentation and innovation with the plantain and cooking banana created a rich diversity of new types. As a consequence, there emerged secondary centers of banana diversification outside Asia—one with plantain in the west-central African rainforest, and the other with the highland cooking banana in the region of Lake Victoria. Today we can recognize some 120 plantain and 60 banana cultivars that were developed in these two areas. This could not have been easily accomplished. Vegetative reproduction ensures the exact transfer of the parent’s genetic material to progeny. Africans could only have realized the remarkable array of varieties through patient observation and selection of desirable traits for cloning. Genetic studies have estimated the mutation frequencies at which the African cultivars accumulated their distinguishing characteristics. The research suggests it would have taken some two thousand years for the African plantains and perhaps half that for the highland bananas.26

In providing tropical Africa a productive dietary staple, the banana plant encouraged an agricultural transformation of the African humid tropics. Banana cultivation made significant contributions to population growth and, by releasing more people from farming, facilitated new kinds of trade relations and political centralization in and around the Congo Basin and the Great Lakes region of East Africa.27 The history of the banana plant in Africa illuminates the agricultural skills and innovative practices that African farmers mastered and continuously developed in the millennia prior to the arrival of Europeans.

The plantain and banana were thus well-established African dietary staples when Portuguese navigators ventured down the continent’s Atlantic coast in the first half of the fifteenth century. Portugal’s motive was to find direct gateways to the fabled sub-Saharan source of the gold trade that crisscrossed North Africa.28 However, different commercial interests beginning to form off northwest Africa would soon give new impetus to Portuguese activities on the adjacent mainland. The movement of the plantain/banana from Africa into the Atlantic world is part of that story.

The early migration of plantains and bananas begins with the fifteenth-century maritime expansion of Portugal and Spain to two island archipelagos off the coast of Morocco, the Madeira and Canary islands. Settlement was driven by a new kind of “white gold,” sugar, demand for which would propel the burgeoning Atlantic economy. Sugar was a revolutionizing commodity. It demanded considerable labor to tend and cut the fields and feed the cane through the sugar mills, tasks that over time increasingly fell to enslaved Africans. But this workforce also required nourishment—basic foodstaples necessary for human survival. The plantain’s arrival on the Atlantic sugar islands coincided with the importation of enslaved Africans for whom it was a longstanding dietary preference. The plantain/banana first comes into historical view on the Canary Islands, whence clones were introduced to Spanish Santo Domingo. But the plantain was assuredly a frequent passenger on the Portuguese caravels that transported African slaves to these island chains.

The Madeira Islands were the first prominent site of European sugar outside the Mediterranean.29 For the Portuguese who discovered the island archipelago in 1418, it had the virtue of being the closest of the Atlantic islands to the Iberian Peninsula. The Madeiras lie approximately 350 miles west of Morocco. Settlement of the principal Madeira island was underway by the 1420s, and despite the profitable felling of its vast forests for timber exports (“Madeira” is Portuguese for “wood”), a superseding interest in agriculture resulted in complete deforestation by the end of the decade. Introduction of sugarcane quickly followed, with exports to England recorded in 1456.30 Madeira soon became the single largest sugar producer in the Western world, anticipating by half a century the plant’s diffusion to the New World.31

Cane cultivation on Madeira Island itself was supported by a connected system of irrigation aqueducts, conduits, and tunnels designed to deliver mountain water to agricultural fields below. Eventually spanning a distance of over four hundred miles, construction of the levadas was a remarkable though dangerous and back-breaking feat on an island only thirty-seven miles long. Nonetheless, it served the nascent sugar industry well by providing a reliable water delivery system that supported its rapid expansion.32 In this early period, sugar cultivation used different forms of labor, some of it paid, others enslaved. Slaves included Guanche captives native to the Canary Islands, Moors from Morocco, and increasingly after the 1440s, sub-Saharan Africans.33 By the 1480s, the Madeiras’ sugar expertise had transferred to the Canary Islands, the archipelago located to the south. The expansion of sugar cultivation inevitably hastened the demand for slave labor.34

The island chain of the Canaries is situated off the coast of southern Morocco. In contrast to the Madeiras, the Canary Islands were inhabited by a people known as the Guanches when fourteenth-century European cartographers marked the islands on their maps.35 Portugal used the islands as a way station for collecting wood and water for voyages along the African coast. Decimation of the native Guanche people began in 1402 with the conquest of Lanzarote, the island nearest the African mainland. Those Guanches not killed were enslaved. A protracted military conquest of each island continued over much of the fifteenth century, despite fierce Guanche resistance and continuing disputes between Spain and Portugal over the archipelago’s ownership. In 1479 the Treaty of Alcaçovas ceded the Canaries to Spain. In return, Spain acknowledged Portugal’s claims to the Madeiras, Azores, Cape Verdes, and trading posts on the African littoral.36 The Spanish defeated the last of the Guanche insurgency on Tenerife in 1496. Decimation and enslavement of the remaining native peoples cleared the way for sugarcane. On Grand Canary Island, it was planted immediately following pacification of the Guanches in 1483.37 Spain thus followed Portugal’s lead in establishing sugar in the Atlantic islands.

Within ten years, Christopher Columbus had begun his series of historic voyages to the Americas, and he stopped in the Canaries during each outbound journey. By then a sugar economy based on slave labor was in full flower. Columbus, in fact, introduced sugar to Santo Domingo with cane taken from the Canary Islands during his second voyage in 1493. He was already quite familiar with sugar; Columbus had apprenticed in the sugar trade on Madeira fifteen years earlier in 1478.38

As the sugar economy of the Madeiras and Canaries grew in the second half of the fifteenth century, so did the demand for slaves to work the cane fields and mills. The supply of Guanches, some of whom were exported to Madeira during the founding decades of Atlantic sugar production, diminished as Spain exerted full control over the Canaries (the Guanches were reported to be nearly extinct by 1540).39 The demand for slaves led the Portuguese and Spaniards to the African mainland. The easternmost Canaries—Lanzarote and Fuerteventura—are, for instance, located just sixty miles from mainland Morocco. Spanish raids along the Moroccan coast supplied the Canary Islands with Berber slaves, livestock, and camels.40 Meanwhile, Portuguese expansion to the African mainland had begun as early as 1415 with the taking of Ceuta across the Straits of Gibraltar. Ceuta supplied slaves to Lisbon and the Madeiras, as did slave raids along the African coast.

The geographical focus of the slave trade shifted decisively in the 1440s, when Portugal established its first trading post at Arguim, an island adjacent to Mauritania and within reach of coastal peoples, especially the dense populations found south of the Senegal River (Rio de Canagua).41 Figure 2.3, an early sixteenth-century map of this stretch of the African coast, shows the slave port’s proximity to the livestock-herding Azenegues, who lived north of the Senegal River and whose proximity to Arguim made them vulnerable to slave raiders.42 The trade in enslaved Africans gained momentum as Portuguese navigators extended the metropole’s reach with journeys south along the Guinea coast. By 1460 they were in Sierra Leone; the equator was crossed in 1475, and the Congo River reached by 1483. The Portuguese established a sugar colony on the island of São Tomé in 1485. From the 1470s, Portuguese mariners were in repeated contact with Bantu-speaking peoples of west-central Africa for whom the plantain was a dietary staple.43

FIGURE 2.3. Map of region north of Senegal River, early sixteenth century.

SOURCE: Pacheco Pereira, Esmeraldo de situ orbis, opposite p. 24.

In a rehearsal for the greater historical drama to come, enslaved Africans were steadily replacing Guanches and Moroccans in the sugar fields of the Atlantic islands. The ethnic shift in the sugarcane workforce over the second half of the fifteenth century coincided with the appearance of the plantain in the archipelagos. The historical record credits the Portuguese with introducing the banana plant to the Canaries sometime between 1402 and the 1480s, when ownership of the island chain was in dispute and conquest of the Guanches underway.44 More likely the plantain arrived after midcentury, when Portuguese caravels began carrying slaves from African societies long familiar with its cultivation and consumption. As with sugar, the history of the banana plant in Spain’s New World colonies begins at the gateway of the Canary Islands. Dominican friar Tomás de Berlanga took clones from the Canary Islands with him to Santo Domingo in 1516.45

Although Spain established a toehold in southern Morocco (a disputed polity today known as Western Sahara), the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494 effectively divided the known world between Portugal and Spain. In return for granting much of the new territory of the Americas to Spain, the treaty effectively left most of Africa under the control of Portugal. One important consequence was that Portugal became the initial supplier of enslaved Africans to Spanish America until its monopoly in the transatlantic slave trade was contested by other European powers in the seventeenth century.46

Spaniards and other Europeans often wrote of “figs” in initial encounters with the unfamiliar banana plant. The Italian Antonio Pigafetta, chief chronicler of Magellan’s circumnavigation of the globe for the Spanish crown, filled the nomenclature void by using the word “fig” to describe the crew’s first experience with the banana in the western Pacific in 1521.47 Huguenot Jean Barbot used the same name for the African foodstaple on his slave voyage to Guinea in the late seventeenth century. He drew it alongside another plant he encountered, the maniguetta pepper tree or melegueta pepper—the medicinal and spice that had been carried by trans-Saharan caravans to medieval Europe (figure 2.4).48 However, Portugal’s early presence in western Africa during the formative period of the Atlantic slave trade likely explains Portuguese exposure to and adoption of the African common name “banana” used in many Guinea coast languages. Garcia da Orta, a Portuguese physician and botanist who traveled from Portugal to India in 1534, made an explicit reference to the “figs in Guinea, which they [Africans] call bananas.”49 In his journeys to Congo and Angola in 1578–79, the Portuguese Duarte Lopez used the African language name to refer to this important foodstaple: “a great quantity of fruit is found here, named bananas by the natives.”50

FIGURE 2.4. Illustration of banana and maniguetta (melegueta) pepper tree, late seventeenth century.

SOURCE: Barbot, “Description of the Coasts of North and South Guinea,” in Churchill, Collection of Voyages and Travels, vol. 5, pl. F, opposite p. 128.

In the early sixteenth century, Valentim Fernandes described the banana as “the best thing to eat” on the African island of São Tomé. Dutch mariner Pieter de Marees wrote of its pleasant taste on his visit to Lower Guinea in 1600. However the first “banana” introduced to the Madeira Islands was more likely the African plantain, which became known there as banana da terra in Portuguese. The same term was used to reference the cooking banana in sixteenth-century Brazil.51 Thomas Nichols, who enumerated several introduced crops he saw on his visit to Madeira and the Canary Islands in 1526, used the Spanish word plátano to describe his first encounter with the plantain:

This Island hath singular good wine … and sundry sorts of good fruits, as Batatas, Mellons, Peares, Apples, Orenges, Limons, Pomgranats, Figs, Peaches of divers sorts, and many other fruits: but especially the Plantano which groweth neere brooke sides, it is a tree that hath no timber in it, but groweth directly upward with the body, having marvelous thicke leaves, and every leafe at the toppe of two yards long and almost halfe a yard broad. The tree never yeeldeth fruit but once, and then is cut downe; in whose place springeth another, and so continueth. The fruit groweth on a branch, and every tree yeeldeth two or three of those branches, which beare some more and some lesse, as some forty and some thirty, the fruit is like a Cucumber, and when it is ripe it is blacke, and in eating more delicate then any conserve.52

The description of the plant being ripe when its skin was black indicates that the reference is to the plantain, as the fruit banana is not usually eaten this way. Plantains, which can be consumed at every stage of their development, are sweetest when the peel has turned black. The sweetness of the ripened plantain contributes to our inability to pinpoint when true fruit bananas were first brought from Africa to the Atlantic islands and the Americas.53

European powers that established a slave-trading presence in sub-Saharan Africa eventually all adopted the word “banana” (or “banano”) for a food crop that was increasingly important to the commerce in human beings. The Spanish, effectively denied footholds in tropical Africa by the Treaty of Tordesillas, referred to both the cooking and fruit banana in the Canary Islands and Spain as plátano. Peter Martyr, an Italian who served in the Spanish court prior to his death in 1526, puzzled over use of this word for a plant that bore little resemblance to the “plane tree which is in no way related to it.” But Martyr did aver that the plátanos of Hispaniola originated in “that part of Ethiopia which is commonly called Guinea.”54

Portuguese adoption of the African word “banana” parallels adoption of the plant as a foodstaple on slave ships and in the Atlantic islands. As the sugar economy there increasingly turned to enslaved African labor, a longstanding African dietary staple simultaneously gained a subsistence role in the Atlantic archipelagos. This occurred long before Portuguese navigators reached the Asian regions where Magellan’s crew had encountered the “fig” in 1521. The plantain emerges from the background of the Atlantic’s first sugar islands as a principal foodstaple. The diffusion of the plantain from Guinea to the Madeira and Canary islands signals an early instance of the growing significance of food to the emerging Atlantic economy and of the reassertion of African dietary preferences among the continent’s deracinated slaves.

The plantain was not the only African food crop to become a passenger on Portuguese vessels during the late fifteenth century. Rice also makes an early appearance, both in the first reports of Portuguese explorers visiting Atlantic Africa, and later in the cargo manifests of vessels returning from there to Lisbon. Alvise da Cadamosto explored the Senegal and Gambia rivers in 1455 and 1456. Observing the Gambia’s Mandinka, he wrote “they have more varieties of rice than grow in the country of Senega.”55 The rice Cadamosto encountered was the African species Oryza glaberrima, and he provides one of the earliest accounts of European interest in this indigenous food crop. A vessel carrying the grain arrived in Lisbon from the Guinea coast in 1498—a year before Vasco da Gama completed his epochal return voyage from rice-growing India. The earlier date supports the likelihood that this rice delivery to Portugal was the African species.56

Plantains and rice are two crops that are typically claimed as examples of the Columbian Exchange, as plants Portuguese mariners introduced from Asia. However, each was a significant and longstanding dietary staple in Atlantic Africa when the Portuguese first ventured southward along the continent. In the decades before caravels reached the Indian Ocean, the plantain had been adopted as a subsistence staple in Madeira and African rice imported to Lisbon. Where there were African foodstaples, there were enslaved Africans, and in the fifteenth century enslaved Africans were present in significant numbers in the workforce of Lisbon and the Madeiras.57 Muslim expansion into Africa in the seventh century similarly encountered societies for whom plantains, rice, and sorghum had been dietary staples for thousands of years. African accomplishments in plant domestication and crop development are not made explicit in either expansionary movement to the continent.

Iberian incursions along western Africa brought them in contact with a diversity of cereals and tropical tubers, some entirely novel and others previously known through Muslim introductions. The principal African foodstaples that the Portuguese encountered at the beginning of the transatlantic slave trade are depicted in figure 2.5.

Columbian Exchange scholarship that attributes intercontinental crop transfers to Iberians assumes that Iberians also had a deliberate hand in planting and propagating these crops elsewhere. Early written accounts that present African food plants such as the plantain and banana as novelties and new discoveries profess both curiosity and ignorance, revealing little if any prior familiarity with the ways they were grown. Attributions of Portuguese and Spanish agency in establishing these foodstaples in the Atlantic islands and in tropical America divorce the plants from the purpose they served. Ignored is the role of the plantain and other African foodstaples in the provisioning of slave ships, and the motivation that transplanted slaves themselves might have had in initiating cultivation of longstanding food preferences. By neglecting fundamental consideration of a people historically active in the domestication and breeding of plants and animals, and active even under conditions of bondage, the classic literature of the Columbian Exchange unwittingly contributes to the perception that Africa and its peoples were inconsequential in botanical history.

FIGURE 2.5. Principal African foodstaples on the eve of the transatlantic slave trade, ca. mid-fifteenth century.

Alfred Crosby in his book Ecological Imperialism drew attention to the role of anonymous immigrants in the intercontinental transfer of species and the shaping of newly encountered landscapes into so-called Neo-Europes. But we should also consider another chapter in the history of intercontinental transfers. In this instance, the migration was not voluntary, but forced; the immigrants were not European, but African and enslaved; and the plants involved were tropical species from Africa. These African plant transfers were unlike any other discussed in the Columbian Exchange literature, for they occurred as vital supports of the transatlantic slave trade.