The Blacks eat large quantities of these fruits…and are used to putting them in water in order to make it more tasty.

There is also a fruit called “cola”…which quenches the thirst and makes water delicious to those who make use of it.

THE LITERATURE ON THE TRANSATLANTIC slave trade largely focuses on the commodities exchanged between Europe, Africa, and the Americas. In the classic formulation known as the Triangle Trade, Europeans sold firearms, iron bars, spirits, textiles, and beads in Africa in order to purchase slaves. Slaves were carried from there to the New World, and from the Americas the commodities produced by enslaved labor were transported to Europe. Sugar, coffee, and tobacco became items of everyday European consumption. But missing from this narrative is the critical importance of food to the entire enterprise. Only through the availability of food could each segment of the Triangle Trade operate. The exchange of commodities between three Atlantic continents depended crucially on keeping the enslaved Africans that were its key component alive over the Atlantic crossing. The foodstaples that provisioned slave ships provide the bridge for understanding the means by which African dietary staples arrived in New World plantation food fields.

Although maize, manioc, and other Amerindian crops helped to fulfill the enormous subsistence demand created by the transatlantic traffic in human beings, African species were likely put aboard every single ship that crossed the Middle Passage. They were stowed as provisions, meat, medicines, spices, lamp oil—even flavorings to improve drinking-water quality. Slave ships became the unwitting vessels of Africa’s botanical heritage by carrying seeds, tubers, and the people who valued them to the Americas. Similar to the way in which European botanists of the time used the African bottleneck gourd as a watertight container for shipping specimens to scientific and commercial collaborators, the slave ship likewise conveyed African species to the Americas.

This botanical legacy is not evident in the commodity focus of scholarship on the Atlantic slave trade and plantation economies. It is better illuminated through the lens of subsistence, the food that served as the daily fare of the enslaved. The African components of the Columbian Exchange come into sharp relief by engaging how the need for food shaped the transatlantic slave trade.

The captains of slave ships who purchased African foodstaples knew little of the crops with which they provisioned their vessels, much less the ways these unfamiliar foods were grown. In fact, slavers often referred to these tropical African staples by generic terms: cereals were known as the “corn” of Guinea, beans by the slave ports where they were loaded, and all manner of tubers were simply called “yams.” Slavers’ fundamental concern was an expeditious provisioning and speedy departure so that they could safely—and profitably—land a boatload of captives on the other side of the Atlantic.

Although the African components of the Columbian Exchange journeyed to the Americas because of slavers’ actions, the establishment of African foods in plantation societies followed a different course. The plant introductions owed their presence in slave food fields to Africans themselves, who took the initiative in planting their dietary preferences from the leftover provisions that at times fortuitously remained from slave voyages. This testifies to an unusual form of botanical transfer, one that occurred with the arrival of enslaved Africans and was driven by their resilience in adversity.

Perhaps as many as twelve million people were forcibly deported from Africa over three and a half centuries of Atlantic slavery. Of this number, at least ten million made it to the New World alive. The forced migration of enslaved Africans to the Americas involved an almost inconceivable number of transatlantic journeys. There is now supporting documentation for at least thirty-five thousand slave voyages to the Americas, but many without doubt went unrecorded. More than seventeen thousand occurred in the eighteenth century alone.1 Even this number puts into perspective the enormity of the demand for slave-ship provisions along Africa’s Atlantic coast. For every ship that boarded slaves in Africa, the success of the enterprise rested on the ability to find enough food surpluses to keep alive a boatload of human beings—often several hundred—on the open ocean for the duration of the Atlantic crossing.

Ship captains estimated the subsistence needs of their captives from a formula that allowed two daily meals on a transatlantic voyage ideally expected to last between three and six weeks. The French slave ship The Diligent, for instance, used a generally accepted provisioning rule of one ton of foodstuffs per ten captives.2 Some estimates of food purchases are evident in the documentary record. Captain Thomas Phillips purchased five tons of rice along the Rice Coast on his 1693–94 voyage; James Barbot bought rice in the same region for his slave voyage across the Atlantic in 1699. One ship captain, John Matthews, estimated that he needed 700 to 1,000 tons of the grain to feed the 3,000 to 3,500 slaves awaiting shipment from Sierra Leone.3 For the 250 slaves the Sandown carried to Jamaica in 1793, Samuel Gamble purchased more than eight tons of rice, cleaned as well as in the husk (Gamble purchased the grain in the husk because it was offered at a lower price than the milled rice brought from the interior by caravan).4 In seventeenth-century Angola, slave-ship captains calculated a measure of just under two liters of manioc flour per captive per day, plus one-fifth of a liter of African beans or “corn,” or flour made from the shell of oil palm nuts.5 In 1750 John Newton loaded his ship with cowpeas and nearly eight tons of rice for the 200 slaves he carried across the Middle Passage. The slave ships Fredensborg and The Diligent stocked millet (likely sorghum) and cowpeas as provisions; others carried pigeon peas. In the Bight of Benin, yams and plantains frequently were sold as provision. The Diligent purchased at Príncipe one thousand plantains as food for its captives.6

A slave ship departing Europe for the African coast brought some food stores, such as salted meat and fish, cheese, biscuits and wheat flour, beer and wine, intended for the most part for the officers and crew. After months at sea it became a monotonous and often moldering diet, which was relieved by additional food purchases once the ship arrived in Guinea. A variety of African foodstaples and essential goods could be bought from African societies, including grains, legumes, even supplies of hippopotamus and elephant meat.7 In one transaction, slave trader Theophilus Conneau described the diverse items offered for purchase. A seven-hundred member Fula caravan arrived at the Atlantic coast with thirty-six bullocks for sale, an unspecified number of live sheep and goats, fifteen tons of rice along with forty slaves, thirty-five hundred cattle hides, and nine hundred pounds of beeswax.8

However, this critical provisioning could take weeks, if not months, depending on circumstances such as food availability, competition from other embarking slave ships, and the number of slaves to feed. These factors could compel a slave ship to put into many different ports along the African coast in order to fill its stores. For instance, William Littleton, who traded in the drought-prone Senegambia region for eleven years in the 1760s and 1770s, observed that slave ships calling there seldom obtained sufficient quantity of millet and sorghum for the Middle Passage, forcing them to journey south to the Grain Coast for (African) rice.9 Areas known for their ability to supply slaves often could not provide adequate provisions to all the ships that called there. The sheer number of slave ships operating along the Slave Coast meant that most had to travel elsewhere to find provisions. Like the eponymous Banana (Plantain) Islands, São Tomé and Príncipe became specialized as provisioning way stations that grew plantains and other tropical tubers.10

While captains hoped to fill their larders quickly, sometimes several months went by before they could secure the necessary supplies. Delays greatly increased the risk of disease outbreak as well as the threat of revolt by slaves already boarded. Some accounts of slave traders mention the scarcity of provisions, rather than the availability of slaves, as the main impediment to embarkation. One seventeenth-century trader along the Slave Coast addressed the issue of seasonal food shortages:

In the months of August and September, a man may get in his compliment of slaves much sooner than he can have the necessary quantity of yams, to subsist them. But a ship loading slaves there in January, February, etc. when yams are very plentiful, the first thing to be done, is to take them in, and afterwards the slaves. A ship that takes in five hundred slaves, must provide above a hundred thousand yams; which is very difficult, because it is hard to stow them, by reason they take up so much room; and yet no less ought to be provided, the slaves there being of such a constitution, that no other food will keep them; Indian corn, [fava] beans, and Mandioca [manioc] disagreeing with their stomach; so that they sicken and die apace.11

But the problem of food availability was a continuing one. In the early nineteenth century, the Portuguese governor of Angola ordered arriving slave ships to bring sufficient manioc flour for the return voyage to Brazil.12

Stimulating demand for traditional African foodstuffs was the view that more Africans survived slave voyages if they were fed the food to which they were accustomed. The belief that familiar foods reduced slave mortality influenced slaver purchasing preferences, though they were not always realized. But the perceived linkage between customary subsistence staples and survival contributed to a sustained demand by slavers for traditional African foods.13

However, provisioning a slave ship with African staples hardly meant that slaves were being served customary food. Their meals typically consisted of beans mixed with some sort of starch. Legumes formed an important component of the food slaves were fed. Europeans at times substituted horse (fava) beans for the indigenous ones they found along the Guinea coast: black-eyed peas, pigeon peas, lablab or hyacinth beans, and the indigenous Bambara groundnut.14 These were mixed with cereals, yams, or the flour of manioc into a starchy gruel, made only slightly more palatable by seasoning with African palm oil and melegueta pepper.15

When European slave ships arrived along the African coast—several weeks journey from northern Europe to the Cape Verde Islands, an additional month to the Gold Coast, some three to four weeks in total to Angola—they needed to replenish dwindling, and often stale, supplies of water as well as firewood for cooking fuel.16 Ship captains paid a fee or provided gifts to African chieftains for the right to take on water and cut trees in places where they were known to be available. The success of any slave voyage depended vitally on the availability of drinking water and food. Inadequate supplies could result in high mortality. Each vessel required below deck a considerable storage space for holding barrels of water, which could not be replenished en route.

Captains estimated their water needs based on anticipated days at sea and daily per person consumption. The log from The Diligent, which left France for Africa’s Slave Coast in 1731, calculated one sixty-gallon cask of water per captive. This would provide an allotment of three quarts daily per slave on a typical transatlantic voyage of eighty days, of which one quart would be used in cooking the souplike gruel they were fed. However, half that amount and less was observed as the daily ration on many English, Danish, Dutch, and Portuguese slave voyages that took place over the eighteenth century. Because of the prevalence of dysentery aboard slave ships, some captains believed it best to provide slaves little water.17 When an Atlantic crossing was prolonged because of calm seas, the amount of water allotted captives could be reduced to pitiful amounts, just spoonfuls with each meal.

Consumption of foul water was believed responsible for the dysentery and disease outbreaks that frequently occurred on slave ships. Captains were especially concerned about the quality of freshwater along the Slave Coast, which they believed caused worms and scurvy.18 The search for supplies of good water led them to offshore islands or other specifically recommended locales along the coast:

Tho’ this [water] of St. Tome [São Tomé] keeps pretty well in casks, after it has once stunk, and is recovered. I would advise such as resort thither to victual their ships, to water in other places in the island, or in the middle of the town, through which the river runs, tho’ it will cost double the labour and charges. For it is so essential a point, that the water taken aboard in slaveships should be of the very best and cleanly, that it often contributes very much to save or destroy whole cargoes of them, according as it is good or bad; and rather than to run a risque, I would advise them to go to cape Lope [Gabon], Prince’s Island [Príncipe], or Annobon for it; because many ships have lost the best part of their compliment of slaves by that water, in their passage from thence to America.19

On lengthy sea voyages a ship’s water often spoiled: “In fact, it seems to have gone through cycles of going bad and curing itself again.” Nonetheless, in the eyes of some slave dealers, this water, whether good or bad, was preferable because it remained the substance to which Africans were naturally habituated. Some Dutch accounts mention that when slave vessels reached American ports, the captives were only gradually weaned from the stagnant water carried from Africa.20

Water stored in casks on long voyages was vulnerable to microbial growth, often unhealthy to drink, and frequently unpleasant to taste. Several additives were thought to act as water purifiers and to improve its palatability. One was brandy, which was also esteemed for its medicinal properties. Another was the African tamarind. One slave owner described how “in Africa the Negros make a Drink of it, mixed with Sugar, or Honey, and Water. They also preserve it as confection to cook and quench Thirst; and the Leaves chewed produce the same Effect.” Slavers adopted the African practice of making the seeds into a tart pulp to improve the flavor of water. They also stocked the seeds as a medicinal, believing that “tamarinds are excellent for combatting scurvy.”21

Another African plant that played an especially important role in improving the taste of fetid water was the African kola nut. When chewed without swallowing, it made, in the words of the French slaving captain Chevalier Des Marchais, who traveled to western Africa between 1725 and 1727, the “bitterest, or sourest Things taste Sweet after it.”22 Visiting the Gambia River in 1623, Richard Jobson described them “like the bigger Sort of Chestnuts, flat on both Sides, but the Shell is not hard. The Taste is bitter, but the Effect is so esteemed, that ten of them is a Present for a King; for the very River-Water, drank after chewing it, relishes like White-Wine, and as if mixed with Sugar.” One European, Wilhelm Johann Müller, based at Danish Fort Frederiksborg on the Gold Coast (1662–69), mentioned Africans using the kola nut “when drinking so that their drink may taste better,” while others wrote that it imparted a pleasant, sweet taste to water and forestalled hunger pangs.23

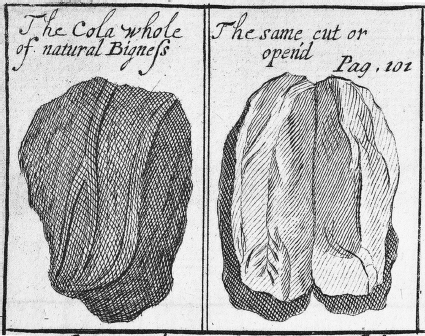

Willem Bosman, a Dutch trader who worked on the Gold Coast for fourteen years at the end of the seventeenth century, mentioned that “not only the Negros, but some of the Europeans are infatuated to this fruit” for the kola nut’s value as a diuretic and to “relish” palm wine (which otherwise became sour after a day or so).24 Jean Barbot, who participated in two slaving voyages to Guinea in the late seventeenth century, elaborated on a plant that he depicted and likely employed: “There is also a fruit called ‘cola’ and by others, ‘cocters’, which quenches the thirst and makes water delicious to those who make use of it. It is a kind of chestnut, with a bitter taste. . . . Here is a drawing [figure 4.1], showing it both whole and cut open down the middle. I give it natural size. The outside is red mixed with blue and the inside violet and brown.”25

Africans prized kola as a stimulant; its level of caffeine considerably exceeds that of coffee (Africa’s other notable indigenous stimulant). Over the sixteenth century, ancient kola nut trade networks expanded to burgeoning coastal markets, perhaps in part because the nuts were loaded aboard slave ships to curb hunger and thirst and to freshen the taste of stagnant water and food. Recent scientific experiments show that stale or impure water becomes quite palatable after chewing kola. This may result from chemical changes affecting the tongue, which create an illusion of sweetness, or may be related to kola’s high caffeine content.26 These properties are succinctly captured in the advertising slogan of the world’s favorite soft drink, “the pause that refreshes,” whose signature ingredients are based in part upon the African plant.

Slave voyages undoubtedly contributed to the early presence of the kola nut in New World plantation societies. One report from 1634 mentions that newly landed African slaves in Cartagena were given kola nuts as a stimulant and medicinal.27 Kola was certainly used for more than curing bad water. As a stimulant, kola may have already become an important medicinal component of Afro-Caribbean populations, as it was in Africa. Moreover, kola nuts are prominently featured in the liturgical practices of the Afro-Brazilian candomblé religion. The transport of the kola nut on slave ships provided the means to reestablish an important African stimulant in tropical America. The continued use of African language names for kola—bissy, goora, obí—that persist in tropical America attest to the plant’s enduring importance among populations descended from enslaved Africans.28

FIGURE 4.1. Illustration of kola nut, near Cape Mount, Liberia, late seventeenth century.

SOURCE: Barbot, “Description of the Coasts of North and South Guinea,” in Churchill, Collection of Voyages and Travels, vol. 5. pl. V, opposite p. 107.

The proportion of male to female captives was often a concern of slave-ship captains, even if their preference was to buy adolescents and young adults. Drawing upon three slaving voyages between 1727 and 1730, the British captain William Snelgrave recommended a gender ratio of three males for every female captive; his French contemporary Chevalier Des Marchais, who also slaved in Lower Guinea, wrote in the 1720s that women should not form more than one-third of the ship’s captives.29 The recommended ratios were at best ideals. The gender composition of the captives on slave ships, while manifestly calculated with the perceived demands of foreign slave markets in mind, may not have been wholly determined by commercial or even arbitrary motives. It may also have been informed by recognition of a logistical need to keep a critical proportion of women onboard during the Middle Passage for the essential function of food preparation.

There were marked differences in the gender makeup of Africans available to slave merchants along Atlantic Africa. For instance, some regions of Upper Guinea, such as Senegambia, showed a distinct preference to retain women in indigenous slavery, which encouraged the export of twice as many males as females.30 In fact, some slave captains in the area complained of shortages of women slaves. John Tozer wrote in 1704 from Gambia that his ship had “never caryed above 60 Men & all ye Rest woomen & children [elsewhere, but] here are all men.” In the same year, Captain Weaver writing from Portodally, Senegal, experienced a similar problem and worried about the surfeit of men and its impact: “he hath not been able to purchase a woman and there must be at least 12 Women to dress the Victuals.”31

Weaver’s comment reveals his dependence on African women to assist in the preparation of food for captives during the Atlantic crossing. Pressing enslaved females into mess duty may have been common practice; it certainly appears to have been so on voyages from Senegambia. The number of slaves on board a slave ship could be in the hundreds, and the vastly outnumbered crew would be primarily occupied with nautical duties and guarding their human cargo. According to historian Hugh Thomas, “Female slaves were often asked to work the corn mill, the corn being put, perhaps with rice or peppers, into the bean soup.” A journal entry from the slave ship Mary (outbound from Senegal), dated June 19, 1796, recorded female slaves milling rice and grinding another cereal, likely millet: “Men [crew] Emp[loye]d tending Slaves and Sundry Necessaries Jobs about the Ship…. The Women Cleaning Rice and Grinding Corn for corn cakes.”32

From the start, food preparation influenced the basic design and outfitting of a slave ship. First, the wood-burning cooking area, normally located below deck, was removed to a position above deck. This was done to heighten security of the galley area in the event of a slave revolt. Slaver captains typically relocated the cast-iron cooking hearth to the quarterdeck near the lodgings of the ship’s officers, where enslaved women and young children were held.33 A nineteenth-century French lithograph illustrates the enclosed cooking area (with chimney) and its location in proximity to enslaved females (plate 2). Also shown is the wooden partition or barricade that segregated the male from female slaves on the ship.34 A door in the partition facilitated the passage of food at mealtimes, when small groups of enslaved males were allowed on deck to eat. The lithograph shows a cauldron of food being passed through the barricade to male captives. Weapons and violence are prominent and pervasive—weapons to maintain control of a slave population that could outnumber the crew by a ratio of thirty or forty to one—but so is food, upon which a successful Atlantic crossing also depended.35 The stove’s location on the female side of the partition placed the women in easy proximity if drafted into food preparation for the ship’s complement of captives.

Slave merchants sometimes bought food already processed, such as milled rice or couscous made from millet. Accounts of Portuguese traders on the Upper Guinea Coast from 1613 to 1614 even record purchases of the small-grained native African cereal fonio (Digitaria exilis).36 But captains of slave ships also bought as supplies indigenous African cereals in the husk, that is to say, not yet milled. Rice, millet, and sorghum could be purchased more cheaply in this manner, but labor availability also may have affected how these grains were bought.37 Loaded onto a slave ship, raw grain could not be eaten unless the husks were first removed, and this could only be done by hand. Milling, and food preparation in Africa in general, was traditionally the work of women.38 The crews of slave ships (such as the Mary) that used women for “Cleaning Rice and Grinding Corn” simply exploited existing cultural practices by drafting enslaved females to pound and winnow unhusked African cereals. Captains Tozer and Weaver, for example, plied the region of the Upper Guinea Coast where the food supplies primarily consisted of millet, sorghum, and rice. If the cereals were not bought already milled, they would have to be processed onboard—or “dressed,” as Weaver put it—perhaps illuminating his concern for the lack of female slaves. On such voyages, the specialized skills monopolized by African women may have been as prized as they were on the fluvial slaving expeditions along the Senegal River.

The milling of cereals was not easy work, as Richard Jobson underscored in his voyage to the Gambia River in 1620–21. “I am sure there is no woman can be under more servitude, with such great staves wee call Coole-Staves [pestles], beate and cleanse both the Rice, all manner of other graine they eate, which is onely womens worke, and very painefull.”39 Hand-milling was not only strenuous work; it also required skillful application of the African mortar and pestle. The African mortar, an upright hollowed-out cylinder carved from a tree trunk, and used with a handheld pestle, was in fact the only known way to separate rice from its husk in the Atlantic world until the advent of competent milling machines in the late eighteenth century.40

Slave ships that provisioned with grain still in the husk stocked milling devices appropriate for their stores: grinding stones or iron rollers for maize, the mortar and pestle for unhusked African cereals.41 On a visit aboard an American slave ship that had stopped in Barbados en route to Savannah, Georgia, Dr. George Pinckard in early 1796 described slaves milling rice: “Their food is chiefly rice which they prepare by plain and simple boiling. …We saw several of them employed in beating the red husks off the rice, which was done by pounding the grain in wooden mortars, with wooden pestles, sufficiently long to allow them to stand upright while beating in mortars placed at their feet.”42

This slave ship had arrived in Barbados from Africa’s Grain Coast and evidently carried as provision rough or unmilled rice, which required pounding to ready it for consumption, even as the ship lay in port. The red husks in Pinckard’s description moreover indicate that the rice was the indigenous African glaberrima species.

Other accounts of slave ships make the gendered basis of milling unhusked grain more explicit. The journal of the slave ship Mary described “females cleaning rice,” while British naturalist Henry Smeathman, writing from Sierra Leone in the 1770s, observed: “Alas! What a scene of misery and distress is a full slaved ship in the rains. The clanking of chains, the groans of the sick and the stench of the whole is scarce supportable…two or three slaves thrown overboard every other day dying of fever, flux, measles, worms all together. All the day the chains rattling or the sound of the armourer rivetting some poor devil just arrived in galling heavy irons. The women slaves in one part beating rice in mortars to cleanse it for cooking.”43

An eighteenth-century oil painting (ca. 1785) provides additional evidence that African women were indeed put to work hand-milling unhusked cereals aboard slave ships. Detail from a depiction of the Danish slave ship Fredensborg shows two female slaves at work on the quarterdeck near the mizzenmast (plate 3). Each one holds a lifted pestle to pound grain in the mortar between them. The Fredensborg was known to be provisioned with “millet,” and the women are likely milling grain that was purchased in the husk.44 The painting provides visual confirmation that enslaved women labored in food preparation on some slave ships and that they used the African mortar-and-pestle technology for milling.

While it was quite common for slaving voyages to end with depleted stores and their human cargo nearly starved, this was not always the case. Some ships reached the Americas with leftover provisions. Pinckard’s comments on the slave ship he visited in Barbados provide one instance. Another account from South Carolina in the 1690s traces one early rice shipment to the arrival of a “Portuguese vessel…with slaves from the east, with a considerable quantity of rice, being the ship’s provision…but was not sufficient to supply the demand of all those that would have procured it to plant.”45 It is important to note that rice suitable for planting must be unhusked; that is, unmilled grains with the outer hulls still intact. Once the husk is removed by milling, the grain cannot be planted and is useful only as food. Taken together, these historical observations directly implicate the slave ship as an agent of botanical dispersal. Each example captures this discrete and seemingly accidental mechanism of seed transfer from Africa. Thus, we find in the ports of New World plantation societies a propitious alignment of the fundamental ingredients for establishing African cereals in the Americas: seeds of African provenance, the presence of people skilled in their cultivation and processing, and individuals for whom the cereals were a preferred dietary staple.

The slave ship is also the vessel for rice introduction in the oral histories of the descendants of runaway slaves (known as Maroons). These stories, which can be heard even today in isolated Maroon communities across northeastern South America, begin with the arrival of a slave ship. In a version from French Guiana, an African woman onboard the ship takes rice seeds and hides them in her hair before she is disembarked. This, her Maroon descendants claim, is how they came to grow rice.46 Another version of the same narrative, from Pará, Brazil, makes the woman’s children the agents of rice dissemination. The mother, afraid that she cannot prevent their imminent sale and separation, tucks grains in her children’s hair, bestowing a gift of lifesaving food from Africa. Like other disembarkation narratives, this version underscores the role of a female ancestor in promoting the diffusion of an African dietary preference in the Americas.47

However, a story from neighboring Maranhão adds an illuminating coda to the Pará narrative. The Itapecurú-Mearim watershed, located inland of São Luis, is a low-lying area where rice initially was planted as a subsistence staple before becoming, in the mid-eighteenth century, the regional locus of a plantation economy.48 This version makes explicit the African origins of rice and undercuts claims of European agency:

An enslaved African woman, unable to prevent her children’s sale into slavery, placed some rice seeds in their hair so they would be able to eat after the ship reached its destination. As their hair was very thick, she thought the grains would go undiscovered. However, the planter who bought them found the grains. In running his hands through one child’s hair, he pulled out the seeds and demanded to know what they were. The child replied, “This is food from Africa.” So this is the way rice came to Brazil, through the Africans, who smuggled the seeds in their hair.49

By embellishing the Pará tale in a crucial way, the Maranhão version illuminates another layer of social memory and historical consciousness. When the white man discovers the seeds in the child’s hair, he reveals complete ignorance of them. Upon learning what they are, he seizes the grains as his own. The child’s explanation of the significance of rice as African food constitutes the planter’s first lesson in the uses of rice. In drawing attention to seeds and their appropriation by planters, the story symbolizes a transfer of knowledge from enslaved African to white owner. In this case, not only is the child the instructor of the man, the slave is the tutor of the master, and the black the teacher of the white. The usual power relations between master and slave are inverted, as are the traditional accounts of European inventiveness and ability. African seeds and funds of knowledge benefit the white man, and the story figuratively encapsulates the historical transformation of rice from an African-grown subsistence crop to a slave-produced plantation commodity.

Seen as allegory, the narrative challenges a Eurocentric narrative of agricultural development in the American tropics that would exclude African agency and initiative. The development of rice plantations in Maranhão depended on the appropriation of African expertise and labor, symbolized as the slave owner taking away the rice seeds brought from Africa. In casting the European “discovery” of rice as something akin to theft, the Maranhão story reclaims rice as a legacy of the African diaspora.

In attributing rice beginnings to their ancestors, Maroon legends reveal the ways in which the enslaved gave meaning to the traumatic experiences of their own past while remembering the role of rice in helping them resist bondage and survive as fugitives from plantation societies. These oral histories offer a counternarrative to the way transoceanic seed transfers are discussed in Columbian Exchange accounts. They substitute the usual agents of global seed dispersal—European navigators, colonists, and men of science—with enslaved women whose deliberate efforts to sequester rice grains helped reestablish an African foodstaple in plantation societies. The stories link plant transfers to the transatlantic slave trade, African initiative, and the dietary preferences of the enslaved. Each narrative sharply contrasts with written accounts that credit European mariners with bringing rice seed from Asia and the initiative and ingenuity of slaveholders in “discovering” the suitability of rice as a plantation commodity in the New World. Importantly, the vessels of European botanical transfers metamorphose into slave ships carrying African peoples and seeds.

These Maroon stories need not be taken literally. While they cannot be substantiated by European accounts, they do accord with certain documented episodes. Slave ships occasionally arrived in the Americas with leftover rice suitable for planting, the technology for removing the hulls, and people for whom it was a dietary staple. We may never know exactly how African seeds and rootstock went from the ship to the shore, from the pier to the plot. But we know that they did, and that this occurred early in the colonial period and in many plantation societies.

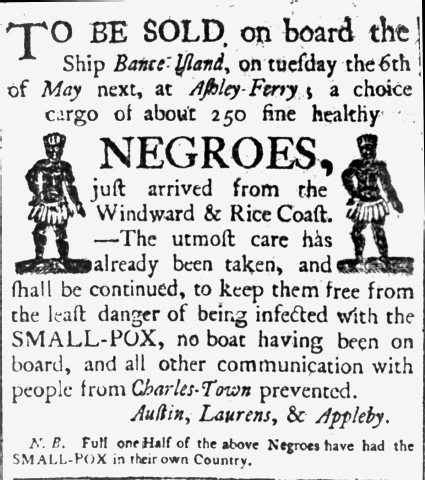

FIGURE 4.2. Advertisement for slave sale, announcing the arrival in “Charles-Town” (Charleston) of Africans who specialized in rice cultivation, ca. 1760.

SOURCE: Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division LC-USZ 62–10293.

An unintended, and perhaps ironic, consequence of slave voyages is that some may have indeed provided slaves the opportunity to access the seeds and roots of African crops as planting stock. In leftover provision on slave ships, enslaved Africans found the means to reestablish the continent’s principal food crops in the Western Hemisphere. The slave voyage may have ended at the auction block (figure 4.2), but Africa’s botanical legacy did not. African food plants abetted the struggle to keep alive both the body and the social memory of lost homes and lives. These plants nourished and sustained African lives and African identities in desperate and brutal circumstances.