In slavery, there was hardly anything to eat. It was at the place called Providence Plantation. They whipped you… Then they would give you a bit of plain rice in a calabash. … And the gods told them that this is no way for human beings to live. They would help them. Let each person go where he could. So they ran.

Perhaps the people of Brazil have to thank my great-great grandfather for these plants.

THE FIRST GENERATIONS OF AFRICANS who arrived in the Americas found themselves in environments not yet wholly transformed by European colonization. The outposts of empire fronted vast tracts of unknown territory, and these provided refuge for many enslaved Africans who opted for freedom. Despite the dangers, some runaways were able to form or join free communities of other escapees in the hinterlands that lay outside the bounds of colonial authority. They escaped to rugged environments whose inaccessibility discouraged pursuit and provided defensible shelter. Indeed, through most of the eighteenth century, more slaves in the New World gained their freedom as escaped maroons than by legal manumission.1 In the mountainous regions of the Caribbean and mainland tropical America, in concealing rainforests above river rapids in the Guianas and Colombia, in swamps and other inhospitable refugia of mainland North America and Mexico, communities of runaways persistently took root beyond the peripheries of white control. Survival depended on their ability to evade detection and capture, or to wage battle—but also on the skills and knowledge that could wrest reliable supplies of food from the harsh surroundings.

Wherever maroon communities gained a toehold, colonial authorities inevitably recruited armed militias to seek them out, destroy their redoubts, and capture the inhabitants. They often met fierce resistance. Palmares—the most famous maroon settlement of Brazil’s early history—ably defended itself from repeated military attack for nearly the entire seventeenth century.2 Otherwise, paramilitary forces managed to reduce most enclaves, but not all. In some areas the numbers of maroons were so large and defensive tactics so effective that the colonies negotiated treaties granting some groups their freedom, as occurred repeatedly in Dutch Guiana in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.3 Other maroon communities evaded destruction by retreating to more clandestine areas until emancipation by the state made their freedom a fact. The Amazon Basin supported many such refugee communities, as did mountainous regions of Brazil, Hispaniola, Jamaica, Cuba, and the French Caribbean. Today, maroon societies continue to occupy some of these remote locales, and one can still discern a distinctive culture whose agricultural practices and plants reveal unmistakable links to Africa. Even vanquished maroon settlements speak to us through the accounts and maps left by the expeditions sent against them. From all of these sources, we learn of the fundamental importance of the agricultural systems that supported subsistence, and the crops that sustained the maroon struggle for freedom.

Agriculture shaped the lives of the majority of Africans landed in the Americas. Subsistence practices and food preferences of slaves offer one way to see manifestations of the African botanical legacy in the New World. Another is through the subsistence strategies developed by maroons. Liberated from the ceaseless toil of chattel slavery, maroons hunted and farmed for themselves. Survival and liberty crucially depended on diverse cultural knowledge systems that would make tropical soils yield. Maroons could plant foodstaples presumably of their own choosing—even labor-intensive crops such as rice and cassava (manioc). All that stood between maroons and the exercise of African dietary preferences in tropical America was the availability of African seeds and rootstock.

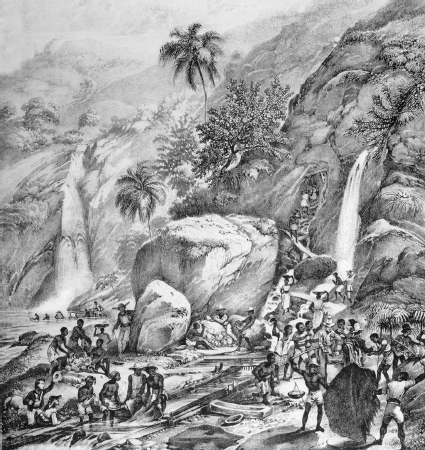

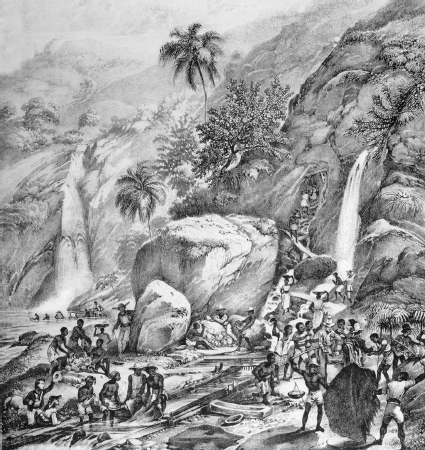

The discovery of gold in the Minas Gerais region of southeastern Brazil in 1695 added a new dimension to the colony’s dependence on slave labor. Demand for slaves was traditionally driven by coastal sugar plantations; now it expanded to the newly discovered goldfields of the mountainous interior. Fortune seekers poured in and mining operations proliferated along riverbeds and hillsides. Nuggets were captured by sieves, while gold dust was trapped by immersing livestock hides in running water (figure 5.1). The mines were immensely productive and profitable: over the course of the eighteenth century, Brazil created 80 percent of the world’s supply of gold. The discovery of diamonds in the 1720s added new impetus to the importation of African slaves, and the slave markets of west-central Africa continued to supply the demand.4 Mining, like sugar, was carried out on the backs of enslaved laborers (figure 5.2, plate 4).

FIGURE 5.1. Illustration of gold washing, Brazil, ca. 1821–25.

SOURCE: Rugendas, Viagem pitoresca através do Brasil, pl. 3/22, following p. 166.

Food supplies in this new El Dorado were chronically short during the first frantic years of the gold rush. In the stampede to get rich, agriculture was largely ignored. Mine owners in the Minas Gerais region often denied slaves the right to plant provision grounds and frequently ignored the law allowing them Sundays and holy days for cultivating their own food.5 Famine threatened on several occasions; predictably, slaves were the first to feel its effects. The brutal labor regimes of the diamond and gold mines, compounded by food scarcity, resulted in high rates of slave mortality.6 Slaves repeatedly turned to flight. As in other New World slave populations where food shortages were endemic, hunger stoked the resolve to escape. The rugged montane terrain of Minas Gerais offered the hope of freedom and safe refuge.7 Mutually intelligible African languages at times abetted flight from slavery. Many of the arriving Africans were speakers of the same subfamily of Bantu languages, which meant that they could understand each other with little difficulty.8

FIGURE 5.2. Illustration of panning for gold, Minas Gerais, Brazil, by Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius, ca. 1817–20.

SOURCE: Spix and Martius, Travels in Brazil, opposite the title page.

As escapes proliferated, maroon communities—known in Portuguese as quilombos (from the Kimbundu word kilombo)—sprang up in inaccessible mountain areas. The fugitives sited their hideaways inside forests and near reliable water sources. They used surrounding rock formations as defensive structures and for surveillance of approaching danger. By the 1720s, runaways from gold and diamond mines in Minas Gerais had founded three major concentrations of quilombo settlements. The largest (estimated to have numbered six thousand people, including some Amerindians and whites) was known as Campo Grande. Its leader was reputed to be an African prince whose military defeat in his homeland led to his enslavement. Campo Grande was actually a cluster of quilombos in which satellite agricultural enclaves formed the periphery of a central and more defensible core settlement. The quilombos combined African and Amerindian agricultural practices and crops, emphasized self-sufficiency in food production, and worked the land together in common fields. They relied upon trusted commercial agents and miners as market intermediaries to trade gold dust, precious stones, woven goods, and livestock products (from cattle and sheep they raided) for other essentials.9

By the mid-eighteenth century, the Campo Grande quilombos increasingly were seen as obstacles to the expanded occupation of the area by ranching and mining interests.10 Two of the enclaves, Ambrósio and São Gonçalo, were repeatedly attacked by paramilitary armies; the former was decimated in 1746 and finally destroyed in 1759 along with São Gonçalo. The militias sent against them made a point of burning community food fields and subsistence reserves. The ruins of these quilombo settlements, still very much in evidence in the 1760s, were mapped by a new expedition led by Inácio Correia Pamplona that returned to find maroons not taken during previous campaigns.11

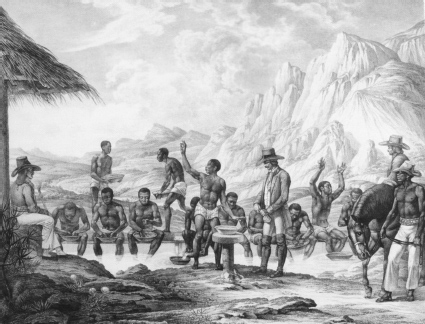

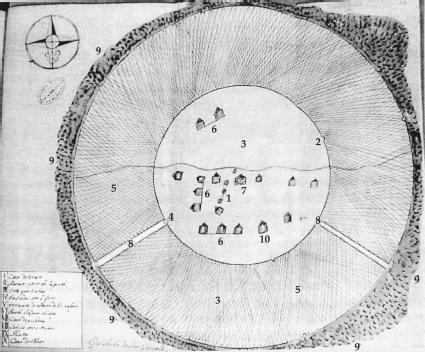

Figure 5.3 shows the strategic siting of the Ambrósio enclave as recorded by the Pamplona expedition. It was located next to a swamp (#4) in the Serra da Canastra. Protected by the arms of a river tributary (#5) and guarded by a mountaintop sentinel (#2), the village compound was surrounded by a rampart and defensive trenches (#1, #6, #8), one of which was booby-trapped with staked pits. Access to the center was controlled by sentry posts (#3). Dwellings (#7) were located within the perimeter, agricultural land and pasture outside it (#9). The Pamplona expedition could not help but admire the tenacity of their maroon quarry, who had resettled the area after eluding capture a decade earlier. There, the military force saw a beautiful, extensive field planted to maize.12

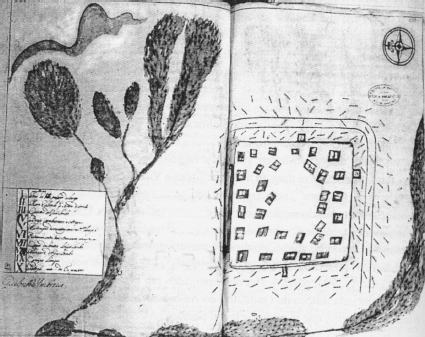

The ruins of neighboring São Gonçalo (figure 5.4) provide insights into quilombo land use. Inside the defensive structures (#2, #4, #8) was a central residential area with dwellings (#6) and a food garden (#3). Located within the central ring were also granaries and structures vital to the community’s survival: a structure with looms (#10) for weaving cotton and wool, another for ironworking (#1), and a hut with mortars and pestles (#7). An outer ring (#5), trenched for additional protection, likely held farmland and pasture. It was in turn surrounded by an unbroken arboreal perimeter, composed of natural forest (#9). This vegetative barrier kept livestock from straying and the entire community hidden from view. As with the other maroon encampments in Minas Gerais, the São Gonçalo quilombo combined agriculture with animal husbandry.

Legend:

1. Palisade and trenches

2. Mountaintop observation post

3. Sentry posts

4. Marsh with pits and stake traps

5. Gallery forest along streams

6. Defensive perimeter with traps

7. Quilombo houses

8. Defensive ditch surrounding quilombo

9. Agricultural land

FIGURE 5.3. Quilombo do Ambrósio, Minas Gerais, Brazil, ca. 1769, drawn by a member of the Inácio Correia Pamplona paramilitary expedition after Ambrósio’s initial destruction in 1746.

SOURCE: Biblioteca Nacional, Anais da Biblioteca Nacional, 111.

In nearby quilombos, the Pamplona campaign found sheep and cattle; fields planted to cotton, cassava, maize, and beans; looms, mortars and pestles, and mill presses for sugar extraction. The Campo Grande quilombos included many inhabitants who had been born there and had never known slavery. The militia was charged with enslaving their prisoners and starving those who man-aged to elude capture. They slaughtered the cattle and sheep, razed all structures, emptied granaries to supplement their own provisions, torched the grazing areas, and destroyed crops growing in the agricultural fields, lest they serve as food for any who escaped. These military reports indirectly suggest land-use practices and agricultural technologies of an African provenance.13

Legend:

1. Blacksmith structures

2. Holes for escape

3. Garden area

4. Entry with two booby traps

5. Trenches

6. Walls connecting houses

7. Milling structure with mortars and pestles for pounding grain

8. Exit with stake traps

9. Primary forest

10. Structure with weaving looms

FIGURE 5.4. Quilombo do São Gonçalo, Minas Gerais, Brazil, ca. 1769, drawn by a member of the Inácio Correia Pamplona paramilitary expedition ten years after São Gonçalo’s initial destruction.

SOURCE: Biblioteca Nacional, Anais da Biblioteca Nacional, 107.

In the mid-eighteenth century, the majority of escapees living in the Minas Gerais quilombos would have been born in Africa. African technical knowledge undoubtedly helped them master the challenges posed by daily life. Although reliant for the most part on New World food crops, the remarkable application of African agropastoral farming techniques was crucial for maroon survival. Sheep and cattle provide through their manure the means to grow food on the same field year in and out, without loss of soil fertility. Land can be kept in continuous food production by rotating it seasonally between an agricultural field and pasture. Animal husbandry thus allowed maroons to maintain their hidden communities and so avoid the risk of detection that would likely attend relocation to new sources of arable land. Livestock formed the integral component of a survival strategy that enabled maroons to continuously occupy their secluded strongholds.

The Pamplona expedition’s discovery of extensive planted fields, granaries filled with surplus food, and animal herds testifies to the remarkable subsistence achievements of the Campo Grande quilombos. Many of these techniques were not learned from Amerindians, who knew nothing about cattle, sheep, or goats prior to the arrival of Europeans and Africans. Nor did Africans have to look to Europeans for instruction in animal husbandry, as Africa supported, then as now, some of the world’s most practiced herding peoples. The quilombo land-use strategies of montane Minas Gerais—like the African mortar-and-pestle milling devices found in the abandoned compounds—involved skills and technologies that were part of the cultural knowledge systems introduced to the Americas by enslaved peoples.

Over time the quilombos of Minas Gerais were mostly suppressed, but not all were eradicated. Today, south of the extinct Campo Grande enclave, another cluster of quilombos survives in the mountainous terrain of Minas Gerais.14 The settlements date to the eighteenth century, when small groups of slaves managed to escape from the diamond and gold mines of the region. The exceedingly remote location (which is still not connected by a modern road) undoubtedly safeguarded the residents’ freedom until it was legally granted in 1888 with the abolition of slavery in Brazil. In these centuries-old hamlets, one can today see the influence of African food preferences having taken root, undisturbed by the depredations of anti-maroon militias.

Today, a village elder named João Ribeiro is their community leader.15 João is known throughout the state for his efforts to secure the property rights of quilombo communities, who still do not have title to the land their ancestors settled. João tells the story of his great-great-grandfather who was born in Africa and survived the Atlantic crossing on a slave ship where many perished. He was landed in Brazil and sold to work in the mines of Minas Gerais. João says that his ancestor spoke “Kongo” (Kikongo), the language he and other slaves used to communicate and plot their escape. When they did flee, the runaways joined the community into which João was later born.16 In 1988, exactly one hundred years after Brazil abolished slavery, João’s community at long last became eligible under Article 68 of the new Brazilian constitution to petition the federal government for legal recognition of their communal land rights.17 There are over 135 remote hamlets seeking this formal designation today in the state of Minas Gerais. They are not alone: over two thousand quilombos throughout the country have filed similar petitions. This number would seem modest given that more than 40 percent of all slaves brought to the Americas went to Brazil.18

João’s quilombo hamlet retains a remarkable degree of agricultural self-sufficiency. Each household continues to grow much of what they need for subsistence. Surrounding each family’s home is a garden plot, where favorite food crops and medicinals are grown. In these plots are many plants native to the New World, but also a considerable number introduced from Africa. João’s garden, for instance, contains Amerindian cassava, sweet potatoes, maize, peanuts, squash, beans, and chilies. These are growing alongside African yams, (Bambara) groundnut, black-eyed peas, watermelon, sorrel, sesame, plantain (banana de São Tomé), and the bottleneck gourd.19 João also plants bitter melon (or balsam pear, Momordica charantia), an African species that repeatedly appears among the medicinals cultivated by diaspora communities of the Americas. Guinea fowl are raised in the community. They are valued for their meat and eggs and are used in the practice of the Africa-based candomblé religion.20 That the ancient agricultural traditions of two continents would share so equitably the soil in João’s garden seems just, an apt symbol of how the foodstaples of Africa were integrated with the crops of Amerindian America.

The first generations of Africa-born slaves certainly carried experiences, knowledge, and crucial skills from their homelands. Many already were accustomed to growing and preparing Amerindian staples such as maize, manioc, and peanuts, which European ships had carried to Africa in the sixteenth century. Although the New World environments Africans encountered contained many flora and fauna unfamiliar to them, there were other species that would have been recognizable because they belong to plant genera found in both the Old and New World tropics. Nineteen genera from fifteen botanical families occur in both Africa and Latin America.21 Plantation slaves and fugitive runaways alike depended on ethnobotanical knowledge for nourishment, healing, and their collective survival.

Africans in the Americas experimented with plants from their immediate surroundings and incorporated many into their diets, healing, and religious practices. Escaped slaves acquired additional knowledge of New World species in their early and repeated interactions with Amerindians, for initial generations of enslaved Africans frequently worked and suffered alongside them. Whether as fellow slaves or runaways, through exchanges with native peoples, or through their own tropical knowledge systems, Africans adapted to New World environments. They grew Amerindian tropical foodstaples such as cassava and sweet potato, and they learned to identify wild foods and autochthonous medicinals of plant genera found only in the Americas. Africans in the New World also established plants and technologies inherited from Africa—such as rice and plantains, the mortar and pestle for milling grain, and familiar cooking practices.22

We see the cumulative significance of this fusion of African and Amerindian knowledge systems in the longstanding homeopathic medicinal tradition of the circum-Caribbean region. In these areas local people still rely on many plant-based cures (“green medicine”) for the treatment of common ailments. In many areas of tropical America where Maroon ancestors won their freedom, their countrymen hold in high regard Maroon knowledge of the valuable properties of wild botanical species.23

Many slaves arrived in the Americas with medical knowledge and skills as healers. An early example is that of the slave Esteban, one of four survivors of the ill-fated Spanish Narvaéz expedition that shipwrecked off Tampa Bay, Florida, in 1527. A Moor of African descent, Esteban was born in Morocco, where he had been enslaved. He is known to us from the account of the epic journey written by one of the survivors, Cabeza de Vaca. It took the castaways nearly eight years to return overland across the southern flank of North America to Spanish settlement in northern Mexico. As they walked thousands of miles through hostile Indian territory, the linguistic and healing skills of Esteban enabled the survivors to reach New Spain (northern Mexico), located a continent away.24

Another documented example of the medical expertise of an African slave is from colonial New England. During a smallpox outbreak in 1721, the Massachusetts theologian Cotton Mather tested the treatment recommended by his “Coromantee” slave, Onesimus. Onesimus had described to his master the African practice of taking fluid from a mild smallpox infection and introducing it to an incision made on the arm or hand. This technique, called variolation, would typically lead to a mild survivable form of the disease but would thereafter confer lifelong immunity. During the Massachusetts colony’s smallpox epidemic, which claimed many victims, Mather followed Onesimus’s instructions and inoculated his son, who grew ill but did not die. Even though Mather morally justified the institution of slavery because “Negroes . . . had sinned against God,” he nonetheless could capitalize on the medicinal skills of an enslaved African.25

For some slaves, knowledge of a plant cure could lead to manumission. The most famous example is Quassi, an Africa-born man brought to Dutch Guiana as a slave in the early eighteenth century. Quassi was credited with discovering in 1730 the febrifuge properties of a tree found in the colony. The previously unclassified specimen came to the attention of Linnaeus in 1761. Of nearly eight thousand plants Linnaeus subsequently catalogued and named, Quassia amara is the only botanical species named after an enslaved person.26 However, the honor bestowed upon Quassi should be historically situated within the broader ethnobotanical context of his life. Representatives of the same plant genus are also found in the region of tropical Africa (the Gold Coast), where Quassi was likely enslaved. The bark is still prepared into infusions for the treatment of fevers. Significantly, the tree thrives in old farm clearings, where agricultural land is left in fallow. A known healer, Quassi likely observed, and experimented with, a related species regenerating around the plantation landscape.27

Diasporic Africans used both Amerindian and African plants in many of the syncretic religions that developed in the Americas. Several New World species that are botanically related to known African medicinals are featured in the ceremonies of Afro-Brazilian candomblé. They are known by their African vernacular names.28 This suggests that some enslaved Africans identified closely allied specimens of the same genus in the Americas and substituted the New World species for those known in Africa.29 The African plants that did arrive in tropical America were also adopted. For instance, the deities of Africa-based religions in Cuba (known collectively as orishas) are often supplicated with specific plants of African origin. The special dishes prepared for the orisha include okra, black-eyed pea, and jute mallow (Corchorus olitorius). Sesame and guinea pepper (Xylopia aethiopica) are used in the cazuela de Mayombe, a clay vessel where the gods are confined.30 Offerings of particular plants—many African—are also found in Brazilian candomblé ceremonies. These offerings include sesame, tamarind, yams, black-eyed peas, African oil palm, watermelon, bitter melon (Momordica charantia), and the African guinea fowl.31

Plantains, rice, yams, and millet are the cornerstones of traditional West African foodways, cultivated there for millennia prior to the arrival of Europeans along Africa’s Atlantic coast. All were present at an early date as subsistence staples in plantation societies of tropical and subtropical America.32 Found throughout the Western Hemisphere in diverse colonial contexts, these African staples were undoubtedly introduced at numerous times and places. Each crossed to the Americas on vessels departing western Africa and, in doing so, crossed geographical, political, and linguistic boundaries to augment the gardens and food fields of tropical peoples old and new, indigenous and forcibly migrated. Plantains, rice, yams, and millet figure prominently in the landscape of food fields first cultivated by maroons.

For most of these plants we can find historical records that credit Europeans with instigating their cultivation in the New World. For example, the Spanish friar who carried the banana plant to Santo Domingo from the Canary Islands around 1516; Dutch commercial agents who promoted millet as the ideal plant to feed thousands of Africans interned in the slave depots of Curaçao; and Portuguese mariners who allegedly brought rice from Asia.33 For the tropical tubers, yam and plantain, we have no direct claims. Spanish chronicler Oviedo, in Hispaniola about 1514, summarized the dominant perspective on each of these African food crops when he wrote that yams were “chiefly grown and eaten by Negroes.”34 The presence of the new crop among recently arrived slaves to the island suggests the likelihood that enslaved Africans pioneered them.

Just as it had in the mountains of Brazil, marronage persisted throughout Amazonic South America. In the Guianas—an area encompassing British, French, and Dutch colonies—the humid rainforests and swamps that bordered the burgeoning sugar plantations of the coastal regions stood as a forbidding, largely inaccessible frontier wilderness to whites—and as a sheltering refuge to slaves wishing to escape. In these vast uncharted forests, plantation deserters were eventually able to achieve food self-sufficiency. The low-lying tropical environments of the Guianas, and the agricultural basis of the plantations that slaves fled, moreover proved favorable for establishing many African dietary staples. Thus, food systems of lowland tropical America offer another way of seeing the African influence on the collective subsistence and survival of maroons.

During the era of plantation slavery, Suriname (formerly Dutch Guiana; about the same territorial size as the state of Georgia) imported as many slaves as the entire U.S. South over a similar time span. Slavery in the colony was notorious for its oppressive demands on labor and the attenuated life spans of its bondsmen. No less cruel were the punishments meted out to those who attempted escape from the colony’s sugar plantations (exemplified by the mutilated slave encountered by the eponymous hero of Voltaire’s Candide). Nevertheless, many Africans enslaved in Suriname took the risk. Enough apparently succeeded, for by the 1670s official reports evince growing concern over the large numbers of runaways living in the rainforest interior. By 1684—less than twenty years after trading New Amsterdam (New York) for the nascent English sugar colony of Suriname—the Dutch colonial government had signed its first peace treaty with maroons.35

Maroon oral histories offer a view of crop introductions that contrasts decidedly with European claims. Rice figures significantly in the legends of these communities, while the stories themselves speak to its seminal status in Maroon culture. One example is the tale of Paánza, recorded by anthropologist Richard Price in Suriname. It has been told by generations of Saramaka Maroons who traditionally inhabit the upper watershed of the Suriname River. The tale of Paánza is instructive for understanding the significance of seeds, rootstocks, and plantation subsistence fields as food sources critical to the survival of the Saramakas’ founding ancestors. Paánza is a female slave, who one day decides to flee as she is harvesting rice on a plantation. But before she runs, Paánza scoops up some grains of ripened rice and stuffs this seed rice in her hair. She escapes, and brings the grains to the maroons living in the forest. This, Saramaka descendants recount, is how they came to grow rice.36

Price has unearthed evidence that Paánza was not an imaginary heroine of folklore, but a real person. She was apparently the mulatto daughter of an Africa-born woman, who gave birth in Suriname about 1705. Price dates Paánza’s escape to the period 1730–40.37 Her mother had been forcibly migrated to Dutch Guiana in the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century, the period when the colony vastly expanded its sugar economy and accelerated the importation of enslaved Africans.38 The extension of the plantation sector into the rainforest interior of the Guianas from the mid-seventeenth century gave slaves like Paánza greater opportunities to escape.

Price draws upon archival sources to tie the Paánza story to a series of slave revolts on Suriname River plantations that occurred during the last decades of the seventeenth century. One of these, Providence Plantation, was run by settlers of a utopian community of Labadist Protestants.39 Notoriously cruel treatment on this sugar plantation provoked many slaves to escape, as related in this passage from a Saramaka oral history: “They whipped you…. Then they would give you a bit of plain rice in a calabash…. And the gods told them that this is no way for human beings to live. They would help them. Let each person go where he could. So they ran.”40

Through skillful combination of archival records and oral histories, Price connects the uprisings and mass escapes to the founding of the Saramaka Maroons as a people. In this telling, the lack of rice is used to convey the overwork and hunger that motivated Saramaka ancestors to run away and form their founding community. In the story of Paánza, the Saramakas commemorate a dietary preference that abetted their struggle for survival. Together, both stories underscore the centrality of rice to Saramaka life and culture.

The tale of Paánza also draws attention to the instrumental role of a woman of African heritage in the cereal’s geographic dispersal. It shares salient features of the common foundation narrative held by Maroons across northeastern South America: how an enslaved woman introduced rice by using hair to hide the grains, delivering them—in one story—from a slave ship to a subsistence plot, or from a plantation field to a maroon enclave in another.41

To this day rice remains the indispensable daily staple of Maroons in Suriname and French Guiana. Written accounts suggest that Maroon rice culture has changed little over more than two hundred years of observations. Here, rice is a woman’s crop. Females sow the seed in rainforest clearings and harvest the crop by cutting the grain-bearing stalks with a small knife. They bundle the sheaves, carry them back to the village, and mill the cereal by hand with a mortar and pestle.42 Anthropologist Sally Price has written that the cultivation and processing of rice is “the most important material contribution that women make to Saramaka life.”43 In each task, female Maroons are carrying out a cropping system that in fact closely echoes methods long practiced by women across West Africa’s indigenous rice region.44 Maroon rice culture represents more than the geographical extension of an African cropping system, however. Botanical collections made in Maroon communities of French Guiana have found the African rice species present among the types cultivated there. Indeed, glaberrima rice was actively maintained in Maroon food plots.45

Rice is the foundational component of the dishes that Maroons in Suriname have long prepared to commemorate important life passages. The cycle of an individual’s existence closes with funerary offerings of cooked rice. It is also consecrated in “memory dishes” that commemorate ancestors.46 Eighteenth-century Dutch historian J.J. Hartsinck recorded the Maroon practice of serving two rice-based meals during the mourning period that followed a person’s burial.47 The offering of food for the dead is similarly an ancient African practice that continued well into the period of transatlantic slavery. Symbolically perforated ceramic vessels and food remains that predate the beginnings of the trade have been found in funerary rituals and burial sites along the middle Senegal River valley. Food offerings inflect a funeral mass as depicted in mid-eighteenth century Kongo.48

The meaning of rice to the Maroons reaches beyond considerations of taste and the geographical transfer of African dietary preferences to New World plantation economies. The cereal simultaneously serves to articulate a memory of enslavement and deracination—of loss, separation, and forced exile from Africa—as well as one of freedom. It is through women that this collective memory is activated in oral accounts and ceremonial practices. A female ancestor carries precious African seed grains off a slave ship; another removes the grains from a plantation provision field and brings it to the Maroons. Women plant the seeds for subsistence, which enables others to free themselves from plantation slavery and join them. Grains of rice consistently form the coda of a historical consciousness that links the New World descendants of Africans to the continent of their ancestors.

Rice and other African food crops continually surface in colonial documents that pertain to maroons in the Guianas. In 1748 French Guiana, a captured maroon youth named Louis testified during his interrogation that his community planted in their forest gardens “manioc, millet, rice, sweet potatoes, yams, sugar cane, bananas, and other crops.”49 Four of the seven crops he identified (millet, rice, yams, bananas) were introduced from Africa. In Suriname, Saramaka communities that had been pacified by peace treaty were visited in the 1770s by Moravian missionaries who sought to convert them to Christianity. The missionary records also reveal an impressive array of African foodstaples planted in maroon food fields. These include rice, plantains, bananas, yams, the African groundnut, okra, pigeon pea, watermelon, and sesame.50 An 1810 military expedition against maroons of Demerara—the British sugar colony that bordered Suriname to the west—“destroyed rice crops sufficient to feed 700 persons for a year, as well as large amounts of yams, tanias, plantains, and tobacco.” Despite the expedition’s evident success, the crops were established again within a year.51

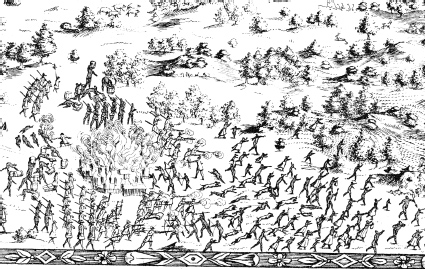

FIGURE 5.5. Militia units setting fire to a Maroon village, detail of the Alexandre de Lavaux map of Suriname (Generale caart van de provintie Suriname), 1737.

SOURCE: Bubberman et al., Links with the Past, pl. 7, p. 127.

Confrontations with maroons are vividly rendered in an illustrated map made by the surveyor Alexandre de Lavaux during a 1730–31 eradication campaign in the Suriname interior. His eyewitness drawings combine in a single tableau details of different assaults against maroon strongholds in the upper reaches of the Saramacca River. Figure 5.5 shows militia units setting fire to a village, which is surrounded by a defensive wooden palisade. Also depicted are the efforts of maroon fighters to cover the retreat of their fleeing compatriots. Their bows and arrows, however, are no match for the advancing soldiers and their muskets.

Figure 5.6, another vignette from the Lavaux map, depicts the razing of another maroon enclave. Volleys of gunshot are fired at the fleeing maroons, and dogs set loose to track them down. Lavaux makes racial differences explicit in his drawings, such as the militia’s enslaved porters and soldiers who, like the maroons, are depicted with cross-hatching to distinguish them from the whites. But one detail in the lower right corner of figure 5.6 catches the eye. Some maroon women are carrying pouches as they flee. The image raises the tantalizing question of what items might have been prioritized in their desperate flight. Could the pouches hold precious seed grains? This is certainly a reasonable speculation given that the ability of the maroons to survive the destruction of their homes and food fields depended fundamentally on their capacity to plant food in a reconstituted community.

FIGURE 5.6. Razing of Maroon enclave, detail of the Alexandre de Lavaux map of Suriname (Generale caart van de provintie Suriname), 1737.

SOURCE: Bubberman et al., Links with the Past, pl. 7, p. 127.

Captain John Stedman was a Dutch-speaking mercenary officer who served in several military actions against Suriname’s maroons. During the years 1773–77 his militia fought in the colony’s northeast rainforest and swampy interior—the area between the Cottica, Commewijne, and Marowijne rivers—where maroon settlements proliferated. Stedman wrote extensive eyewitness accounts of his exploits, and his commentaries reveal the extent and productivity of the maroon agricultural fields he encountered.

Stedman noted that food was a priority to maroons fleeing the advancing army; in particular, maroons made great efforts to carry off quantities of grain and tubers, which, he observed, they grew in abundance. On one occasion, soldiers came across hampers of milled rice that were only abandoned when troops overtook the runaways carrying them.52 Stedman’s vivid descriptions of these skirmishes underscore how maroons prioritized food as they fled. But much was left behind in village granaries and unharvested fields. When not put to the torch, these abandoned reserves at times replenished the pursuers’ own dwindling stocks. The militia commissary was so often depleted during these extended campaigns that soldiers were sometimes ordered to harvest the captured fields. It is in a maroon rice field that Stedman describes his first experience milling the grain by the traditional African method:

He [the commander] gave out orders to subsist on half allowance, which he bid the poor men supply by picking rice and preparing it the best way they could for their subsistence…. It was no bad scene to see ten or twenty of us, beating the rice with heavy wooden pestles, like so many apothecaries, in a species of mortar, cut all along the trunk of a leveled purple-heart tree for that purpose, viz., by the Rebels, before they had expected to be honored by our visit. This exercise was nevertheless very painful, and verified the sentence pronounced on the descendants of Adam, that they should eat bread by the sweat of their brow, which trickled down my forehead, in particular, like a deluge.53

As in all maroon eradication campaigns, Stedman’s militia was charged with capturing fugitives and denying any who escaped the means to resist or reassemble. In practice this meant burning maroon agricultural fields, homes, and defensive structures, destroying granaries and other food repositories—in effect, their entire subsistence base. Stedman notes that in just one campaign, soldiers demolished “more than two hundred fields of vegetable productions of every kind.” In a diagram of one captured hamlet, he marked the community’s substantial rice, cassava, maize, yam, and plantain food gardens (figure 5.7). The African crops he encountered in maroon food fields grew alongside Amerindian staples. Stedman even referred to the New World peanut by its African name when he noted its culinary importance to maroons: “The pistachio or pinda nuts they also convert into butter, by their oily substance, and frequently use them in their broths.”54 Other African crops that Stedman repeatedly identified in maroon food gardens included plantain, yams, pigeon peas, okra, and watermelon.55 Stedman’s catalog of crop destruction, however, is also a document of maroon achievement. It reveals unmistakably how Africa’s botanical legacy had taken deep root in tropical America.

Maroon communities in the Guianas and elsewhere drew upon all the cultural resources, knowledge, and skills belonging to their members. Liberty depended on the capacity to ensure daily subsistence. The synthesis of knowledge systems from the Old and New World tropics, initially forged in plantation food fields and then adapted to the swamps, jungles, and mountains of their secluded refuges, was indispensable for maroon efforts to remain free. The result was a new, robust plant assemblage that could be found in nearly all maroon communities of tropical America. It was a considerable subsistence base that included Amerindian cassava, maize, sweet potatoes, and squash, Asian sugarcane, yams (Old and New World types), tannia (New World Xanthasoma or Asian taro), groundnuts (peanuts and the African Bambara groundnut), beans (Amerindian and the African “peas”), peppers (chilies, as well as African melegueta and guinea pepper, Xylopia aethiopica), cultivated “spinach” (from the pantropical Amaranthus species and others), as well as bananas and plantains, rice, sesame, and okra introduced from Africa.56 The African introductions in this tropical food complex form a significant component, and they reveal the re-assertion of African dietary preferences where environmental conditions and freedom from bondage made it possible.

Legend:

| 8. Maroon defensive position |

| 9. Rice and maize field |

| 11, 16. Rice fields |

| 12. Maroon hamlet |

| 14. Old settlement |

| 15, 17. Agricultural fields (cassava, yams, plantains) |

| 18. Protective swamp |

FIGURE 5.7. Detail of a drawing of a Maroon settlement, northeast Suriname between the Cottica and Marowijne rivers, destroyed by the militia of Captain John Stedman in November 1776.

SOURCE: Stedman, Narrative, of a Five Years’ Expedition, 2:128–29.