In the same way that Europeans brought to America plants and seeds that they judged beneficial, so too did the Africans.

Bunched guinea corn [sorghum]…. But little of this grain is propagated, and that chiefly by Negroes…. It was first introduced from Africa by the Negroes.

Cola africana—an African fruit, introduced by the Negroes before [Hans] Sloane’s time [1687–89], called bichey or bessai.

THE HISTORICAL RECORD ON THE question of African plant introductions to the Americas is not so silent as we might suppose. A salient footnote of the plantation period is the number of European accounts that actually credit slaves with the introduction of specific foods to the Americas, all previously grown in Africa. These accounts were mostly written by planters and naturalists of different nationalities, working in colonies throughout the Caribbean and North and Latin America.

These European commentaries inadvertently attribute an agency to enslaved Africans that contrasts with colonist narratives of how slaves came only with their bodies, bereft of farming skills and knowledge, and were given these skills and knowledge by white planters. They also conflict with later claims of planter inventiveness in introducing new crops suitable for cultivation that were in fact longstanding African foodstaples. The commentaries identify Africans as pioneers of crops entirely novel to their masters. They lend support to the significance of slave food fields as staging grounds for the “diaspora” of African food plants. In these sites of subsistence, slaves instigated the cultivation of many dietary preferences without planter guidance or coercion.

Through such accounts, we can identify at least a dozen plants whose introductions to the New World are directly attributed to African slaves. For example, Willem Piso, a naturalist who worked in Dutch Brazil in the 1640s, made drawings of belingela, the African eggplant known at that time in English as guinea squash; he asserted that it was introduced by Angolan slaves, along with okra and sesame.1 Of the bonavist or lablab bean, Piso’s scientific collaborator Georg Marcgraf wrote, “This plant was brought from Africa to Brasil.”2 Sir Hans Sloane, founder of the British Museum who was in Jamaica from 1687 to 1689, wrote of a bean “brought from Africa” that he described as “almost round white Pease something resembling a kidney with a black Eye not so big as the smallest Field pea.”3 This “calavance” pea, so clearly strange and new to him, is the first certain description of the African cowpea in English America, which became known in the colonies as the black-eyed pea, after its distinctive appearance.4 In the Carolina colony, English naturalist Mark Catesby attributed to slaves the introduction of sorghum and millet.5 French botanist François Richard de Tussac (1751–1837), who worked in the colonies of Saint Domingue and Martinique, credited slaves with bringing the cytisus (pigeon) pea to the French Antilles. British historian John Oldmixon (1673–1742), echoing Oviedo’s account of yam introductions to Hispaniola two hundred years earlier, contended that yams “were brought thither [to Barbados] by the Negroes.”6 Luigi Castiglioni, an Italian botanist, wrote during his travels in the United States (1785–87) of a plant that “was brought by the negroes from the coasts of Africa and is called okra by them.”7 Naturalists Johann Baptist von Spix and Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius encountered okra in early nineteenth-century Brazil and wrote, “It seems to have been introduced by the negroes from Africa.”8 Thomas Jefferson claimed that sesame “was brought to S. Carolina from Africa by the negroes.”9

How is it possible that slaves could have introduced all these plants when they were brought to the Americas with few or no personal belongings? Could so many historical commentaries be wrong?

The introduction of African crops is coincident with the arrival of enslaved Africans who had subsisted on these foods during the Middle Passage.10 Hans Sloane touched on the crucial connection between African plants and slave ships when he reported that the African kola nut arrived in Jamaica from “seed brought in a Guinea ship.”11 Similarly, the peanut—a plant actually of South American origin that was introduced to western Africa in the early sixteenth century—made the journey, Sloane writes, on slave voyages “from Guinea in the Negroes Ships, to feed the Negroes withal in their Voyage from Guinea to Jamaica.”12 Captains of slave ships loaded these crops and other African foodstaples onto their vessels to facilitate the transportation of human beings—the kola nut to make spoiled water palatable and the food crops to provision captives during the Atlantic crossing. Once landed, captains of slave ships dispersed their human cargoes and returned to the metropolitan centers of their financial backers. But during the time they remained in port, the occasional surpluses of African seeds and rootstock were likely removed from their vessels. In the early colonial period the principal food crops of the African continent had already become a botanical feature of New World plantation landscapes.

Plantation owners first encountered African crops in the food fields of their slaves. In these subsistence plots (also called “Negro plantations” in historical accounts), Europeans noticed a different assemblage of plants, some of which were entirely new to them. Among the ones Willem Piso identified in seventeenth-century Brazil were okra, sesame, and guinea squash. Hans Sloane added that Jamaican slaves also grew millet, sorghum, rice, and the black-eyed pea in their food plots. Millet “is to be met with in some Negro’s Plantations,” he wrote, “though not so commonly as the former [sorghum].” He found the black-eyed pea “planted in most Gardens, and Provision Plantations, where they last for many years.”13 It was in slave food plots that Mark Catesby observed the cultivation of sorghum and millet in early eighteenth-century Carolina: “These two grains are rarely seen but in Plantations of Negros, who brought it from Guinea, their native Country, and are therefore fond of having it.”14 Jefferson attributed the presence of sesame in the Southern colonies to slaves “who alone have hitherto cultivated it in the Carolinas & Georgia.”15

These commentaries illuminate a shadow world of cultivation that had evolved in the struggle of the first generations of enslaved Africans to ensure food availability. This cultivation system was closely tied to subsistence and emphasized crops that Africans established by their own initiative. It stood in stark contrast to the commodity fields of the plantation, where slaves grew crops under the directives of the slaveholder. In the interstices of the plantation economy, slaves cultivated subsistence crops on many types of food plots. They planted dietary staples that were particularly suited to tropical and subtropical growing conditions and that were often ones they preferred.

It was in “Negro” food plantations and in the yards around slave dwellings where the African components of the Columbian Exchange made their initial New World appearance. European naturalists and slaveholders encountered these new food crops in slave subsistence sites, acknowledging in their comments the role of enslaved Africans. The significance of the African plant assemblage for slave survival, and the cultural funds of knowledge that informed their establishment as subsistence staples, was not lost on Willem Piso in seventeenth-century Brazil. Assessing the fundamental dietary role of a wide range of new tropical food plants that he found in slave food plots, Piso remarked, “In the same way that Europeans brought to America plants and seeds that they judged beneficial, so too did the Africans.”16

In the early period of plantation development, food supplies were chronically scarce. At the end of a rigorous day in plantation labor, food availability depended very much on the extra effort slaves could muster to provide for their own subsistence. One Dutch traveler to Virginia reported in 1679 that the tobacco estates demanded long hours of toil “as if planting [tobacco] were everything.” After an exhausting day, the slaves “still had to pound maize for their food, which was mostly hominy and poor in meat.”17 Acknowledging that the time to tend their food plots counted for just a minor portion of each day, Johann Martin Bolzius observed in Georgia’s early plantation period, “If the Negroes are Skilful and industrious, they plant something for themselves after the day’s work.”18

Overwork and fatigue affected the ability of enslaved Africans to cultivate some preferred foodstaples. Sloane wrote in the 1680s, for instance, that hand-milling made rice more labor-intensive than other subsistence options. “This grain is sowed by some of the Negro’s in their Gardens, and small Plantations in Jamaica, and thrives very well in those that are wet, but because of the difficulty there is in separating the Grain from the Husk, ’tis very much neglected, seeing the use of it may be supplied by other Grains, more easily cultivated and made fit for use with less Labour.” Even so, the pottery that Jamaican slaves produced in the seventeenth century included decorative impressions made with rice grains.19

The labor of plantation slaves was vested not only in the production of export crops, but in the building of the estates themselves. Plantations were carved from forests and swamps cleared by slaves. As only hand tools were available to accomplish this task, the removal of even a single tree demanded considerable work. The stumps and underbrush had to be burned and uprooted before the soil could be cultivated. The physical demands on enslaved workers in the initial period of plantation development made the supply and quality of food vital to their survival. Even in French Catholic colonies where the Code Noir and other metropolitan edicts aimed to enforce planter compliance, slaveholders consistently failed to provide adequate food to their enslaved workforce. Whether for reasons of planter indifference or economic efficiency, food availability depended critically upon the efforts of those already consumed by plantation work to provide for their own dietary needs.

Enforced self-reliance in plantation economies nonetheless had an unforeseen consequence. Arrogation of subsistence obligations to slaves generated both the need and the opportunity to establish many African foodstaples in their provision grounds and dooryard gardens. In pioneering these subsistence foods, slaves strengthened their own food security, diversified the dietary options otherwise available to them, and reinstated some traditional food preferences. These crops gave enslaved Africans the opportunity to choose in part what they consumed, beyond what a plantation owner deemed appropriate or convenient to feed them. Through this narrow window entered the botanical legacy of a continent.

Enslaved Africans established their subsistence staples in three distinct settings: in the individual plots that some plantation colonies granted them, on provision grounds, and in the yards surrounding their dwellings. The relative emphasis on each subsistence practice varied between plantation regions and over time. In the initial period of Brazilian sugarcane development, some slaves were already exercising the right to grow food on individual plots. Gabriel Soares de Sousa referred to these plots in the 1570s–1580s when he mentioned foodstaples that slaves planted.20 Writing about Dutch Brazil in 1646–48, Pierre Moreau described them as “little pieces of land on which, during the limited time they have for rest (after a twelve-hour day) they sow peas, beans, millet, and maize.”21 The subsistence convention of independent production eventually diffused from Northeast Brazil to parts of the Guianas and some Caribbean islands, where it became known as the Brazilian or Pernambuco system, named for the plantation society where it was initially implemented.22

As European slave traders had observed in Guinea over the same era, independent production was initially conferred as a privilege, not as a right universally granted to the slave population.23 In Brazil, Jesuit priest André João Antonil reported in 1711 that it was given to senior slaves, usually those who held their master’s trust. But in the context of chronic food shortfalls, placing slaves in charge of their own subsistence freed planters from the necessity to provide them food rations. Eventually the practice was expanded to include most of the enslaved male population.24 On the Caribbean island of Barbuda, a 1715 inventory instructs that specific slaves be permitted to tend “their provision grounds without interference.” The crops they grew included guinea corn, yams, maize, and legumes (possibly pigeon peas).25 Even so, access to subsistence plots did not ensure slaves the requisite time to produce their own subsistence. They were usually allowed no more than a day a week to work their individual food plots, sometimes just a portion of one weekend day.

Brazilian slaveholders regarded the convention of independent production as a bestowed privilege, easily conferred but just as easily revoked. Slaves considered it a right, as their subsistence security depended upon it. Once it was granted, they resisted any attempts to withdraw it, as two documents first published by historian Stuart Schwartz illuminate. On a Bahian sugar plantation in 1790, a group of runaway slaves put forth conditions for their surrender. The demands suggest that the fugitives had been accustomed to growing food on their own subsistence plots and had been allowed to bring new land into cultivation. They listed as a condition for returning to plantation labor “the days of Friday and Saturday to work for ourselves not subtracting any of these because they are Saint’s days.” They also demanded “the right to plant our rice wherever we wish, and in any marsh, without asking permission for this.”26

Apologists for the Pernambuco system liked to portray independent production as an example of planter benevolence and the inherently civilizing virtues of slavery. These plots after all gave slaves some degree of economic autonomy by way of new opportunities to produce marketable surpluses. In 1784 Brazilian naturalist Alexandre Rodrigues Ferreira opined that independent production provided slaves the means of legal manumission:

Some owners of sugar mills have the custom to grant each slave as much land as he needs, according to his being single or married, and one or two days each week, in order that he can cultivate his plot. From the latter they obtain the yucca [manioc] flour, the maize and the beans for their sustenance and that of their wives and children, thanks to these days they work for themselves each week…. And the fact is, as we know by experience, that not only do they cultivate the yucca flour for feeding themselves, but also they are able to sell almost all agricultural goods as well as many domestic animals, until they accumulate enough money to free themselves and their children.27

Ferreira’s idyllic characterization of independent production in eighteenth-century Brazil is at odds with repeated observations of the chronic inanition of the country’s slaves over the more than three centuries that the institution endured there. Sugarcane production left slaves little time to work their subsistence plots. Nor did economic autonomy through the sale of marketable surpluses generate the revenue by which large numbers of slaves freed themselves. In fact, harsh labor and poor nutrition contributed to the persistent failure of the Brazilian slave population to increase naturally—even after the transatlantic traffic ended there in 1851.28

Historian Barry Higman enables us, however, to place Ferreira’s comments in broader perspective. Writing about the attendant ill health, morbidity, and premature death of sugar workers in the British Caribbean, he has estimated that field slaves worked in sugarcane on average some thirty-five hundred hours annually, or about sixty-seven hours per week. This is equivalent to a modern worker accustomed to a forty-hour work week compressing (without time off ) an additional thirty-five and a half weeks into a fifty-two week year. These figures do not include the extra time that slaves may have spent on subsistence cultivation. The result was an exhausted labor force whose life expectancies remained low.29

Under a sugar labor regime, only the healthy and physically fit could realize the surplus potential of independent production. But the convention of granting slaves an individual plot was a convenient one for planters, as it relieved them of responsibility for the dietary needs of their workforce. Moravian missionary C.G.A. Oldendorp made this point when he wrote about the practice on Danish St. Croix in the mid-eighteenth century: “From this [plot], they are to produce their own means of sustenance. The yield is generally great enough that it provides the diligent cultivator with a surplus beyond his basic needs, and from this he can provide himself with other commodities. This arrangement relieves the master of any further cares concerning the slaves than when the essentials for their sustenance are handed to them in kind, as is the case on several English plantations on St. Croix.”30

Independent production was not the only subsistence system practiced in the early plantation period. In other areas, a portion of plantation land was set aside for the purpose of planting food crops for all the resident slaves. The cultivation of African yams for sustenance on food fields was in fact so common in many parts of the Caribbean that “yam grounds” became a metonym for provision grounds. Many of the southern colonies of mainland North America also adopted the practice of designating specific grounds where slaves grew their collective sustenance.31

However, by the eighteenth century the emphasis on provision grounds for food production was shifting on some sugar islands. The demand for sugar in European metropoles had grown to such an extent that even more land was brought into production. On islands of flat topography, cane cultivation eventually stretched from shore to shore. The acreage in food cultivation severely declined. Alexander Hamilton, born on Nevis but who lived in St. Croix until the mid-1750s, noted the erosion of subsistence security when he recalled that planters “appropriate only small portions to the purpose of raising food. They are very populous, and therefore the food raised among themselves goes but little way.”32

Mountainous sugar islands such as Jamaica responded to the insatiable demand for sugar land by relocating food production to hilly areas, on soils that were marginal for cane, and to other less accessible locations. Although plantation owners sometimes subdivided the distant provision grounds for allocation to individual slaves, they generally showed little interest in the ways that the enslaved managed food production in these remote sites. It was on such distant provision grounds that slaves later in the eighteenth century broadly won the “right to grow their own food crops,” thereby extending the practice of independent production to islands where it previously had no influence.33

On sugar islands of low topographic relief, food shortages grew acute as cane cultivation overtook most of the arable land. Planters responded by importing food for their workforce. A regional trade in food soon developed. Mainland North America became an important supplier, especially of salted fish, salt beef, grain, and legumes.34 Carolina planter Henry Laurens found markets in the British Caribbean for the rice and the black-eyed peas that his enslaved growers produced.35 Subsistence shortages in other sugar-producing areas, such as eighteenth-century Danish St. Thomas, Antigua, and Dutch Guiana, similarly induced some plantations to specialize in the cultivation of food for others. The semiarid island of Barbuda, for example, supplied livestock and crops to Antiguan sugar estates, which lay thirty miles from its shores. Among the crops produced by Barbuda’s slave community were “yams, ‘pease,’ and corn.”36

Slaves on provision plantations thus grew the foodstaples that fed other enslaved workers on food-deficit sugar islands. Both maize and guinea corn were marketed as food rations in the intraregional trade. In the Guianas, provision estates supplied the food-deficit coastal sugar plantations with plantains, eddoes, and pigeon peas.37

This regional provision trade was slave-based and oriented to the production of Amerindian and African subsistence staples—the tropical grains, tubers, and legumes that each cultural legacy had developed for food security. In this food-import economy, some African crops that the first generations of enslaved Africans pioneered in their food fields were fed to their descendants in the form of mass-import rations, as occurred with guinea corn on Barbados and Curaçao.

Despite these regional adjustments in food supplies, the substitution of imported rations for locally produced food narrowed the range of dietary staples available to slaves who toiled on monocrop sugar islands. A food-ration system resulted in an unvarying and nutritionally inadequate diet. Moreover, the physical spaces available for slaves to improve and diversify their diet contracted to just the small yards surrounding their dwellings.38 Vital food options, and the means to express them, disappeared.

The fragile mechanism of food-import dependency broke down during the second half of the eighteenth century. The tumult of serial international conflicts—the Seven Years’ War, the American and French revolutions, and the Napoleonic Wars that followed—severely disrupted the regional food trade. Recurrent subsistence shortfalls resulted in hunger on some islands, outright starvation on others. Food scarcity was in fact a contributing cause of the unrest that sparked the Haitian Revolution in 1791.39 The revolutionary upheavals and disruptions in the Caribbean in the remaining decades of the eighteenth century forced import-dependent islands to return to self-sufficiency as a matter of survival. Land once given to sugar was again placed in provision grounds.

On some of these newly established provision grounds, supervised labor gangs planted the food crops. But this system coexisted with, and was often replaced by, one that increasingly resembled the Pernambuco system, in which slaves were allocated individual plots to grow their own food.40 The practice of independent production grew throughout the Caribbean in the final decades of the eighteenth century. As a consequence, the average size of the food plot allotment in the British West Indies nearly doubled in the fifty-year period 1750–1800, from four-tenths of an acre per slave to seven-tenths of an acre.41

The convention of independent food production was an early feature of the African-Atlantic world. European observers of African societies describe it during the initial period of the transatlantic slave trade. Historian John Thornton discusses its existence in São Tomé, a sugar-producing island off the coast of present-day Equatorial Guinea, through the words of an anonymous Portuguese pilot who visited five times between the 1520s and 1540s. The “rich men of São Tomé had large groups of slaves ranging from 150 to 300 who had the ‘obligation to work for their master every day of the week except Sunday, when they worked to support themselves.’ … The masters ‘gave nothing to the said blacks,’ neither food nor even clothing, which they had to make for themselves from local products in their own time.” The practice drew the concern of Carmelite missionaries on the island in the 1580s, since slaves were given the Sabbath to work for their own subsistence even as they were relieved of their plantation labors on that day. The Carmelites expressed concern that slaves were working “on feast days and Sundays to produce for themselves, which they argued should be days of rest.”42 The Carmelites apparently did not comprehend a practice in which servitude also vested slaves with the right to sufficient time to attend to their own subsistence.

Independent production did not arise sui generis in New World plantations. Its diffusion probably owes as much to conventions of indigenous African slavery as planter strategies to gain economic advantage. Independent production was, for instance, evident during the commercialization of millet cultivation in slave-trading Senegambia.43 The early sixteenth-century chronicler Valentim Fernandes recorded that Wolof slaves worked one day a week for themselves. European commentaries on Senegambia centuries later describe the longstanding tradition in indigenous African slavery whereby slaves typically retained one or two weekdays for their own food production. On the days worked for their master, the practice was to labor from sunrise to midafternoon. The practice of leaving slaves to generate their own food recognized the need to allocate time for its production.

Some slaves held in indigenous African slavery were able to obtain an individual food plot and the time to work it if they distinguished themselves in service to their masters. For those able to achieve this level of trust, independent production conferred a measure of protection against the risk of sale to European slave traders. Such concessions were apparently negotiated individually but were not an obligation of the master.44 The convention of placing slaves in charge of their own subsistence by the grant of independent plots reappeared in the sugar-producing estates of tropical Brazil, but stripped of the protections and rights conveyed in its African formulation. Plantation owners knew little about growing food in the tropics, so putting subsistence production in the hands of their bondsmen represented a practical, if not convenient, solution. What appears as a convention bound by rules and tradition in indigenous African slavery had become an unfettered instrument of economic expediency on New World plantations. Any advantage an enslaved plantation worker may have gained by access to independent food plots was thoroughly subverted to the year-round demands of sugarcane. Altered by the relentless commercial priorities of European slaveholders, the time allotted individual slaves to work their subsistence plots was scarcely a priority.

There is a considerable scholarship on independent production, which discusses the origins and geographical and temporal expansion of the convention throughout plantation societies of the New World tropics. Much has been written on independent production as an economic strategy, with emphasis on the surplus food that slaves marketed and the plots’ role in reducing slaveholder expenses. From the planters’ perspective, independent production enabled them to reduce food allotments to the enslaved workforce or to forgo responsibility altogether. Nevertheless, slaves repeatedly fought for the right to a subsistence plot even when its recognition meant an intensification of their own labor burden.45 This is because the plot represented considerably more than the physical space for growing food. Access to land for independent production gave slaves the opportunity to plant crops without supervision, to produce beyond their dietary needs, to realize petty cash or goods from marketable surpluses, and to derive direct benefits from a portion of their overall labors. Independent production provided both a degree of economic autonomy and an opportunity to strengthen subsistence security. But it was also the genesis of attempts to extract broader acknowledgment that not all of one’s labor was owned by the master. The significance of the institution was the burgeoning notion that an enslaved person had the right to some of the time he or she labored and to the products that came from this work.

The convention of independent production expanded across Caribbean plantation societies over the second half of the eighteenth century following the food shortages induced by the upheavals of European conflicts. These subsistence plots represented the physical sites where slaveholders acknowledged that a portion of plantation labor time and crops belonged to their slaves. Once established, the convention of independent production sometimes served as a springboard for negotiating additional rights, such as the ability to bequeath the subsistence plot to one’s family or a person of one’s choosing, as Woodville Marshall writes of the Windward Islands: “Slave families in the ‘constant occupation’ of provision ground forced their owners to recognize rights of occupancy to portions of plantation ground. Slaves would not move from their [provision] ground without notice or without replacement grounds being provided, and they could bequeath rights of occupancy as well as property.”46

A similar effort was reported (ca. 1815) on a sugar plantation in Northeast Brazil operated by Benedictine monks. “The slaves are allowed the Saturday of every week to provide for their own subsistence, besides the Sundays and holidays . . . and when a negro dies or obtains his freedom, he is permitted to bequeath his plot of land to any of his companions whom he may please to favour in this manner.”47

The right to designate the subsistence plot’s heirs was also reported in the French Caribbean on some of the islands visited by French abolitionist Victor Schoelcher during 1840–42. Just years before the French Republic’s emancipation decree (1848), Schoelcher noted that slaves worked their subsistence plots “communally,” that is, with the labor of family members and other kin. He also reported that they held established rights that slaveholders were compelled to recognize, which included the right to leave the subsistence plot and its produce to their relatives or designated heirs. “They pass them on,” wrote Schoelcher, “from father to son, from mother to daughter, and, if they do not have any children, they bequeath them to their nearest kin or even their friends.”48 From such roots in independent production, the tradition of family land took hold in many parts of the Caribbean.49

The diffusion of independent production as the predominant subsistence strategy in the late eighteenth-century Caribbean brought new challenges to enslaved people. Foodstaple cultivation frequently took place in marginal environments, on soils affected by poor drainage, acidity, and stoniness or in degraded areas such as eroded ravines and mountain slopes. These subsistence grounds often required rehabilitation before they could be coaxed into production. They also necessitated crops that did not require constant attention. Under such subsistence challenges slaves brought to bear the full range of their experience as tropical farmers to make the diverse cultivation environments yield. They stabilized soil banks from erosion by ridging the slope with hoes. They selected dietary staples for ease of cultivation and productivity. Root crops such as plantains, yams, and taro were especially favored. So were legumes such as the tropical pigeon pea, which was appreciated as food but also for improving soil fertility, as provender for domestic animals, and as a plot boundary marker.50

Crops requiring additional care and inputs—typically vegetables, herbs, spices, medicinals—were grown in the dooryard gardens outside slave dwellings, as George Pinckard reported from Barbados in 1796: “On these small patches of garden it is common for the slaves to plant fruits and vegetables, and to raise stock. Some of them keep a pig, some a goat, some guinea fowls, ducks, chickens, pigeons, or the like.” In these locations the work of women and the aged was especially evident. Food wastes and manure from small animals penned in the yard improved the garden’s productivity.51

The changing face of subsistence cultivation on sugar islands over the eighteenth century—from food self-reliance to imports and back again—occurred against the backdrop of the ongoing disembarkation of enslaved Africans to the Caribbean. The new arrivals repeatedly injected African agricultural practices and methods, with important consequences for import-dependent islands where food cultivation had contracted to the yard surrounding slave dwellings. They also brought with them knowledge or experience of the conventions common to indigenous slavery practiced in Africa, conventions stripped away in transatlantic slavery, but experienced as rights by its bondsmen. The steady infusion of enslaved Africans, and the crops and practices descendants of earlier migrations had maintained in kitchen gardens, facilitated the return to food self-sufficiency in the region. This was achieved with the expansion of subsistence cultivation beyond the household plots to provision grounds and independent plots. In such ways, Africans continually shaped the food systems of tropical plantation economies.

The many novel plants that European plantation owners, visitors, and naturalists described in the food fields of slaves enumerate species that we now know are of African origin or were an established foodstaple on the continent during the Atlantic slave trade. Included among the African introductions that Jamaican slaves planted in their food fields were the African oil palm, yam, pigeon pea, banana and plantain, kola, pearl millet, guinea corn, rice, taro, the bottleneck gourd, and okra. The African components of subsistence staples in other plantation societies included hibiscus (known as jamaica in the Spanish Caribbean), black-eyed and lablab peas, the Bambara groundnut, sesame, guinea squash, guinea pepper, melegueta pepper, and jute mallow.52 Such an extraordinary range of African crops made “the slave provision ground,” in the words of one eighteenth-century observer of Saint Domingue, “une petite Guinée.”53

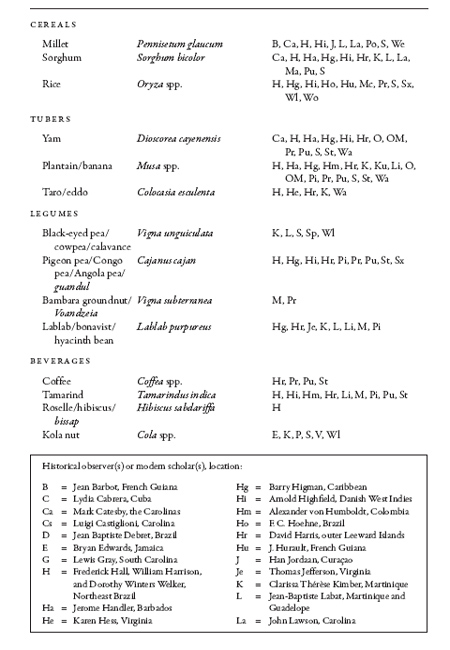

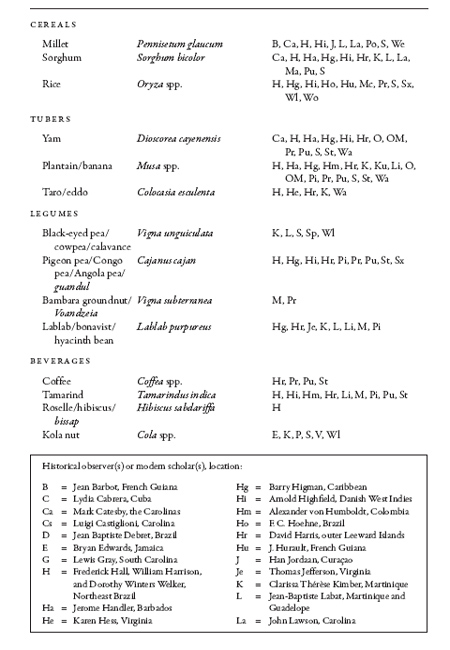

A sampling of the African introductions found in these subsistence sites—as reported by slaveholders, plantation observers, naturalists, and modern scholars—is presented in figure 7.1. The fundamental necessity of food to human life provides the context for understanding the subsistence strategies slaves developed in plantation societies. As European commentaries repeatedly indicate, the African botanical introductions initially gained their New World footing in the food plots of enslaved Africans. In these small and fragmented spaces of food production, Africans realized an alternative botanical vision to the plantation export commodities that were vested with the dehumanizing practices of the plantocracy. Here, slaves organized cultivation for their own purposes, selecting plants that improved their diet, healed their bodies, and provided them spiritual succor in the liturgical practices of Africa-based religions. As informal experimental stations for the transfer, establishment, and adaptation of African food crops and dietary preferences, these plots became the botanical gardens of the Atlantic world’s dispossessed. The apotheosis of this subaltern experience is exemplified in the story of one descendant, George Washington Carver (ca. 1864–1943). Born in slavery in Missouri, Carver gained scientific renown through his work on three seemingly minor crops—okra, the black-eyed pea, and the peanut—each long associated with the African presence in mainland North America and a staple of slave food gardens.

FIGURE 7.1. African plants established in the plantation era.

A critical feature of human migration the world over is the preservation of traditional dietary preferences across space and the dislocations of geography. That the migration of Africans was compelled through extremes of violence and cruelty does not diminish this universal desire or preclude the possibility of achieving it. African staples enabled slaves at times to reinstate some food traditions of specific cultural heritages and to combine ingredients in new ways with Amerindian and European foods. In this way, slaves discretely modified the monotony of any food regimen slaveholders might impose. The introduced African crops encouraged the distinctive foodways that eventually developed across plantation societies. Africans and their descendants thus profoundly shaped the culinary traditions of slave societies, combining in new ways the foods of three continents in their struggle to secure daily sustenance. They moreover realized this achievement under circumstances no other immigrant group had to face. Africa’s botanical legacy in the Americas is built upon this unacknowledged foundation.