Specific foods, no matter how humble in our eyes, excite the same symbolically mediated complexity that foie gras and caviar excite in gourmands, because we are the only animals that have culture, and that’s the big secret, which people are taught but do not really believe. . . . The single most important truth about human beings is the existence of culture.

AFRICAN INGREDIENTS AND COOKING PRACTICES gave the foodways of former plantation societies their distinctive culinary signatures. Their metamorphosis to the diaspora cuisines of today was originally mediated by enslaved women who guided modest foods out of the subsistence plot and into the cooking pot. These foodways began, to borrow the words of historian James McWilliams, as “cuisines of survival.”1 At the hearths of their dwellings and in the kitchens of plantation gentry, African women and their descendants created the fusion cuisines and memory dishes that attest to the African presence in the Americas.

A signature ingredient of the foodways of Africa and the diaspora is greens. Perhaps no other cooking traditions feature them so prominently. In West Africa alone there are more than one hundred fifty indigenous species of edible greens. Twentieth-century botanists identified more than thirty different cultivated species in the region.2 Greens are mentioned in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century accounts of African meals. It may well be that the unidentified plant “the size of Parsley” that Pieter de Marees included in his depiction of foods grown along the Gold Coast in 1602 was one of these edible cultivated greens (see figure 3.5).3 Africans traditionally gather many types of wild plants for food, but women are the principal experts in cultivating, cooking, and marketing leafy vegetables.4 Greens contribute in fundamental ways to stews and the sauces that accompany starchy staples. They are commonly grown in kitchen gardens; such proximity to the hearth testifies to their dietary importance. Greens are a frequent addition to the one-pot stews that have long distinguished African cooking.5

Greens are served in a variety of ways: uncooked as a salad, boiled in side dishes as spinach, mixed in soups and stews or with other vegetables as potherbs, or used as garnishes. Greens generally impart a bitter taste to food, a trait much emphasized in Africa-based cuisines.6 Some greens are prized as thickening agents for soups and stews, such as the leaves of sesame, hibiscus, jute mallow (Corchorus olitorius), the baobab tree, and most famously, okra.7 Each adds a mucilaginous texture, binding the ingredients of soups and stews together. In all of these various culinary guises, greens contribute crucial stores of vitamins, minerals, and micronutrients to the diet.8

The centrality of greens to the food culture of sub-Saharan Africa cannot be understated. When New World manioc was introduced to Angola during the transatlantic slave trade, women experimented with the plant’s leaves for food despite awareness of the poisonous root.9 They discovered that young manioc leaves were not only safe to consume as boiled greens but were also nutritious, as one expert on the usage of manioc in Africa verifies: “The manioc root, although rich in starch, contains very little protein or fat and very small amounts of most vitamins and minerals. . . . The manioc leaves, on the other hand, are rich in protein, calcium, and ascorbic acid, and contain significant amounts of iron and of the A and B vitamins. . . . But when the leaves as well as the roots are eaten, manioc comes close to justifying the name of ‘the all sufficient’ that was given it by natives in southwestern Congo because ‘We get bread from the root and meat from the Leaves.’”10 In many places where manioc is cultivated in Africa, the leaves are cooked and served as spinach or added to sauces as a condiment. Manioc is an example of African culinary innovation with an introduced plant. It is evidence of the ways that longstanding dietary preferences and foodways have guided the adoption of new crops.

The culinary emphasis on leafy vegetables is similarly evident in the cuisines of survival that Africans developed in New World plantation societies. Some greens apparently came to the Americas with enslaved Africans, notably mustard greens and collards. The African eggplant or guinea squash, like sesame and taro, were also cultivated for their edible leaves.11 Greens were used both as food and as medicine. Sorrel or hibiscus leaves, for instance, are prized as a cooked green, and parts of its flower are made into a beverage; decoctions of the dried roots, leaves, and seeds are important curatives in West African and New World diasporic communities.12

Among the edible greens important in diaspora foodways are species that belong to plant genera distributed on both sides of the Atlantic. One is “bitter leaf” (Vernonia spp.), a plant widely used in West African cooking for the taste it imparts to broths and its reputed medicinal properties.13 The Amaranthus genus also includes several species that are consumed as boiled spinaches by Africans and diasporic populations alike.14 The significance of vegetable amaranths in the cooking traditions of Africans throughout the Atlantic world suggests that slaves in the Americas recognized similar members of the genus and substituted a New World species for a familiar African equivalent. The replacement of an African amaranth with a New World cousin is captured in language. Francis Moore, a slave trader who worked along the Gambia River in the early eighteenth century, wrote of one cultivated green, “an Herb call’d Colliloo, much like Spinage,” which he claimed “eats almost as well.”15 Across the Atlantic in Jamaica, the African word callalou refers to spinach made from the leaves of New World amaranth species.16

In many plantation societies, the word callalou named not only the greens of the Amaranthus genus but also the soups and stews that featured them. Eighteenth-century missionary C.G.A. Oldendorp encountered these stews in the Danish Virgin Islands and borrowed the word calelu from the African slaves who prepared and ate them.17 Over time, enslaved women and their descendants working in plantation kitchens transformed this stew into the more richly embellished callalou of our time. Today callalou is recognized as one of the signature dishes of the African diaspora. These flavorful pepper pots of the circum-Caribbean bring together foods from different cultural traditions—African, Amerindian, and European—into a single dish, still known as callaloo (or callalou; caruru in Brazil).18 An important variant of this dish is the gumbo, in which okra substitutes for greens as the principal vegetable. Both callalou and gumbo are African words for African ingredients that lend the dishes their culinary definition. Each expresses the African preference for greens and the continuity of African cooking practices in the Americas.19

Callalou and gumbo are today typically served over rice. But in the plantation era, rice cultivation was limited to a few New World regions and so the cereal was not common fare for most slaves. Where rice could not serve as the starchy base of a meal, diaspora dishes more closely resembled those of African food traditions that are instead based on foodways that use rain-fed cereals or tubers. Willem Bosman, the Dutch factor at the slave fort of Elmina from 1688 to 1702, provided an early description of the two basic meals Africans consumed: “Their common Food is a Pot full of ground Millet or Corn boiled to the consistence of Bread or instead of that Jambs [yams] and Potatoes; over which they pour a little Palm-Oyl, with boiled Vegetables and a little piece of stinking Fish.”20 Bosman’s commentary is one of the earliest European comparisons of two fundamental foodways of the Guinea coast, in which different dietary starches underlie each dish. One builds on a cereal (millet, or “corn”), the other on a tuber. The distinction derives from staple preferences that predominate in different African environments: cereals typically form the basis of meals in savanna areas, tubers in humid tropical regions receiving abundant rainfall. Each typifies longstanding culinary traditions of western Africa.

In more equatorial climates, tubers are the predominant staple and thus often replace cereals in local cooking traditions. The meal Bosman described being made with yams or potatoes is the celebrated fufu of Ghana, Nigeria, and Cameroon. Fufu is made by boiling starchy tubers (plantain and taro are also used) in water until they are soft and then pounding them into a pulp. Continuous stirring in a large mortar causes the glutinous mass to reach a sticky consistency with an appearance similar to, but much thicker than, mashed potatoes. It is then typically spooned into individual servings that are garnished with seasonings, vegetables, and other ingredients. Another way to serve fufu is to mix the toppings directly into the mash.

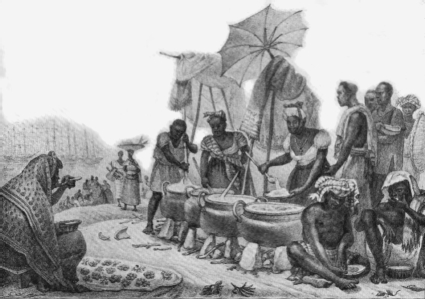

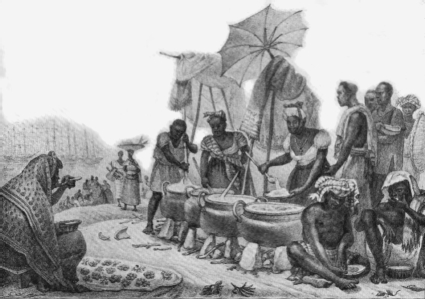

Fufu became important in New World plantation societies where the main carbohydrate derived from tubers.21 The dish was known in Brazil as angú. The early nineteenth-century artist Jean Baptiste Debret depicted a group of female vendors stirring kettles of manioc-based angú, which he wrote was served with okra, greens, and other side dishes (figure 10.1).22 In many parts of the Caribbean, fufu is made with plantains, just as it is in western Africa. The same dish is known in the Dominican Republic as mangú, in Puerto Rico as mofongo, and in Cuba as fufu de plátanos. In each country the emphasis on greens served with a starchy base and prepared in the African way persists.

Bosman also noted the use of cereals as a foundation for an African meal. These “porridges” were traditionally made from sorghum, millet, or fonio but later included maize after its introduction. In the cooking traditions of other cultures, the equivalent starchy formulations would be known as polenta, dumplings, or cornbread. African porridge is prepared by placing unhusked grain in an upright wooden mortar, where it is pounded by hand with a pestle into flour. The flour is gradually added to boiling water until the mixture reaches a thick consistency. The spongy “bread” is then served in bowls to which beans, okra, leafy vegetables, and other ingredients are added. In an alternate version, the porridge is formed into dumplings and dipped into side dishes. A more elaborate preparation, known as kenkey, is made by allowing partially cooked porridge to ferment. The sour dough is then divided into dumplings, which are wrapped with plantain leaves or corn husks and steamed. An illustration accompanying Pieter de Marees’ description of the Gold Coast at the end of the sixteenth century depicts African women selling kenkey (kanquies) in a market frequented by the Dutch (see figure 3.1).23

FIGURE 10.1. Negresses marchandes d’angou (Black women sellers of angú), Brazil, by Jean Baptiste Debret, ca. 1821–25.

SOURCE: Debret, Viagem pitoresca e histórica ao Brasil, vol. 1, pl. 35, following p. 212.

As chattel in the slave ports of Guinea and as prisoners on slave ships, Africans received degraded versions of these basic meals, which had been reduced by slavers to an insubstantial gruel. This gruel became the porridge, mush, or pap of slaveholder accounts. It was left to African women in the New World to restore these diluted staples to familiar African formulations. Several ingredients and dishes of the diaspora bear African names. Some cereal-based porridges of Africa, for example, were known in the Americas as fundi, funchi, or funji. The words likely derive from nfundi, the name reported for the basic porridge of seventeenth-century Kongo, which was served with sauces, greens, and side dishes.24 References to fundi also appear in eighteenth-century records from the West Indies. Dutch documents mention that the “staple food served to slaves at Curaçao was small maize [sorghum]. . . . Small maize was ground into flour and then boiled into porridge (called funchi) or baked into cakes.”25 In the Danish Virgin Islands, Oldendorp described “the everyday food of the Negroes” as maize, cooked into mush or “baked into small cakes or prepared as funji, a kind of large dumpling which is eaten with calelu.”26

The other foundation of diaspora cooking was rice. In rice-growing regions such as South Carolina, Louisiana, Maranhão (Brazil), and the Guianas, maroon and enslaved females innovated with a number of rice-based dishes, some prepared with greens, others with beans of African origin.27 A regional favorite of Maranhão is arroz de cuxá, or rice cooked with sorrel leaves (Hibiscus sabdariffa, called vinagreira in Portuguese). Cuxá is undoubtedly a loan word from kucha, the Mandinka name for African sorrel in the rice-growing region of Senegambia.28

Hoppin’ John, made of rice and black-eyed peas, is a quintessential dish of the southern United States—in particular, South Carolina. It was already a long-established lowcountry favorite when Sarah Rutledge, the daughter of a prominent Charleston slaveholding family, published the recipe in her 1847 cookbook, The Carolina Housewife.29 Although Hoppin’ John is a Southern dish, its contours are distinctly African, with two main African ingredients and origins linked to the slave dwellings and plantation kitchens of the South. Hoppin’ John is traditionally prepared alongside plates of collard greens for New Year’s Day and is reputed to bring good luck to all who have it as their first meal of the year.

As vendors of prepared food, “market women” also promoted a wider acceptance of diaspora cuisines among New World populations (figure 10.2). Cooking and selling food were common occupations of enslaved and free females, much as it was for African women in Guinea’s traditional markets. Female vendors were especially active in the sale of fresh vegetables and fruits. The banana leaf conspicuously draped across the woman’s fruit tray in plate 8 connotes the leaf ’s importance in eighteenth-century cooking practices of Brazil. The banana or plantain leaf provided a wrapper for steamed food in much the same way that the corn husk encloses the tamale in indigenous Meso-American foodways. However, in this image the culinary inflection is clearly African rather than Amerindian. A well-known exemplar of this cooking tradition is abará, a Bahian dish of steamed black-eyed pea meal wrapped in banana leaf.

FIGURE 10.2. A Free Negress and Other Market-Women, Rio de Janeiro, by James Henderson, 1821.

SOURCE: Henderson, History of the Brazil, opposite p. 71.

The market women of plantation societies were variously known as “higglers” and “hucksters” in the British Caribbean and as quitandeiras in Brazil.30 These female vendors also specialized in selling prepared beverages and cooked food (figure 10.3). Through these activities, market women perpetuated African and diaspora convenience foods and drinks. In tropical America, two African beverages are especially popular for their refreshing tastes: tamarindo, made from the pulp of the tamarind pod; and a tart, cranberry-like drink, made from the sepals of the hibiscus flower (Hibiscus sabdariffa), known as flor de Jamaica in Spanish-speaking America.

Notable among the common convenience foods made by enslaved and free women were fritters. A fritter could consist of fish, vegetables, fruits, rice, or cornmeal deep fried in vegetable oil. One variation is the hushpuppy, a Southern favorite made from cornmeal; another is bean cake prepared from black-eyed peas. The latter was sold by market women in South Carolina well into the twentieth century and remains popular to this day in Brazil as acarajé. Both kinds of fritter are made by pounding the main ingredient with a pestle, forming a patty or a ball with the hands, and then deep-frying it in vegetable oil. This West African cooking practice was observed in the fourteenth century. On his journey to Mali in 1352, Muslim traveler Ibn Battuta mentioned fritters made from indigenous Bambara groundnuts that were fried in karité (the French word for the vegetable butter of the Sahelian shea nut tree).31 The vegetable oil of choice for fritters in Africa’s humid tropics comes from the oil palm. It remains a favorite cooking oil of Afro-Bahian cooking, where it is known as dendê (from the Kimbundu word ndende).32 Deep-frying with vegetable oil is an ancient cooking tradition in West Africa that enslaved African women likely introduced to plantation societies.33

FIGURE 10.3. The Quitandeira (The market woman), 1857.

SOURCE: Daniel P. Kidder, Brazil and the Brazilians, Portrayed in Historical and Descriptive sketches (Philadelphia, 1857), 167, in Handler and Tuite, “Atlantic Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Americas: A Visual Record,” database at University of Virginia Library, image ref.: Kidder 7.

The journey of humble foods such as the fritter from West Africa to New World plantation societies to our own place and time speaks to food’s importance as a touchstone of the experience of human migration. Migrants the world over bring their dietary preferences and cooking practices with them. These traditions are rarely forsaken, even when food preferences cannot be reconstituted in full. Food gives material expression to the ways exiles commemorate the past and shape new identities amid alien cultures, diets, and languages.34 Food is vested with symbolic ties to homelands left or lost. The emphasis on meaningful foods and familiar forms of preparation enriches the memory dishes with which migrants connect past and present.

No less than other immigrant groups who came to the New World, enslaved Africans also arrived with specific food preferences and cooking traditions. Few slaves were able to complete the Middle Passage with anything more tangible than their memories. Yet the victualing demands of the Atlantic crossing ensured that Africa’s principal dietary staples were also frequent travelers on slave ships. In the early colonial period, these staples found a New World footing in the spaces slaves cultivated around their dwellings. The violent dislocations of New World bondage could not eradicate the memories of African foodways, and indeed invigorated and perpetuated them because of their importance as means of subsistence and survival.

Food was central to the experience of having been made a chattel slave. For trade slaves bound for the Americas, bondage severed not least the right to partake in the customary foodways that affirmed membership in an African culture. The rupture was reinforced by the degradations of the Middle Passage, and it persisted in the subsistence regimes of New World slave societies, where the enslaved were fed meager rations or left to fend for themselves. Survival depended critically on the extra exertions slaves made to diversify and augment basic needs. But just as importantly, these extra exertions reconstituted and renewed some customary African foodways. Perhaps in no small part it is the cultural memory of slavery and hunger that sometimes makes food, especially food of African origin, a metaphor for migration and loss among diasporic cultures.35

Out of the exigencies of food, diasporic peoples vested many African staples with important symbolic meanings. The annual seú festival of Curaçao, for instance, began as a celebration of the sorghum harvest; in Suriname, yams are prepared for the ancestral offerings made by slave-descended populations; and the New Year’s Day dish of rice and black-eyed peas served in the South since slavery times betokens good fortune. Rice, in particular, is foundational to the commemorative dishes of many Maroon societies. Other African foods are prominently featured in the liturgical offerings of Afrosyncretic religious practitioners throughout the Americas. The black-eyed pea dishes abará and acarajé, for example, are both among the consecrated specialties of candomblé cooking.36

These are all celebrations of food, and it is through the lens of mere food—humble foods—rather than plantation commodities, that we begin to understand the role of Africans in shaping New World farming systems, animal-husbandry practices, and regional cuisines. The marginal spaces of slave food plots offer more insight into this neglected history than the estate fields where they toiled.

African contributions to the global table began with the journeys of several crops across time and space. Nowhere was African agency more transformative than in the oppressive landscapes of New World slavery. The complex relationships of plants and people that were sundered by the Middle Passage were quietly recast by enslaved Africans and their descendants in the food fields and kitchens of plantation societies. What distinguishes the foodways of the African diaspora are their humble beginnings and the discrete ways they infiltrated the plantation palate. What makes them remarkable is the story they tell of exile, survival, endurance, and memory.