Thailand was known as Siam until 1939, when it was changed to Muang Thai or Prathet Thai, which both mean “Land of the Free.” After the Second World War it reverted to Siam for a short period, but became Thailand again in 1949.

It is roughly the size of France and shaped like a tall tree leaning to the right. Thai school children are taught to describe the shape of their country as an elephant’s head with a long dangling trunk. It is bordered to the west and northwest by Burma (Myanmar), to the northeast by Laos, to the east by Cambodia, and to the south by Malaysia, the Gulf of Thailand, and on the southeastern coast by the Andaman Sea.

This is a huge and mostly flat alluvial plain on which Bangkok stands and where a large proportion of Thailand’s rice crop is grown. The hub of the plain is Bangkok, with the twin city of Thonburi across the Chao Phraya River (together they are known as Metropolitan Bangkok).

Metropolitan Bangkok is an enormous, sprawling city of approximately 10 million that has expanded rapidly. The other cities are minnows in comparison. Like many other Third World cities, it is a magnet for the rural poor, and there are extremes of wealth and poverty. It suffers from pollution and gridlocked traffic, but public transportation has improved.

Other important centers are Kanchanaburi, Nakorn Pathom, Rayong, Samut Songkhram, and Phetchaburi, and the resorts of Pattaya and Bang Saen. The population of the central plain minus Bangkok is 14 million.

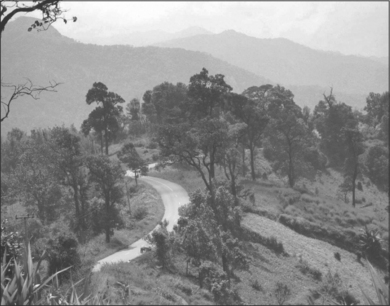

This is the most scenic part of Thailand, full of mountains and hills. Chiang Mai, Phrae, Sukhothai, and Lampang are the main towns, and the region is home to various hill tribes that are ethnically and culturally different from the Thais. The northern dialect differs in some respects from the Thai spoken in the central plains, and is akin to that spoken in the Shan states of Burma. In former times most of this area formed the early Thai Kingdom of Lanna. Population: 13 million.

The Korat plateau is generally regarded as the poorest part of Thailand, and it has less rainfall than other parts of the country. The chief towns are Khon Kaen, Udon Thani (Korat), Nong Khai, Roi Et, and Ubon. The Mekhong River forms a natural border with Laos, and the northeastern Isarn Thai dialect is similar to Lao. Population: 23 million.

This region stretches down from Phetchaburi to the Malaysian border and is only twenty-five miles wide at its narrowest point. It is characterized by lush vegetation and toward the south there are tin and rubber plantations. There are a number of holiday islands off the coast, such as Ko Samui and Phuket. Ranong, Surat Thani, Nakhon Si Thammarat, Songkhla, and the railway junction of Had Yai are the important towns. Population: 10 million.

Thailand has a tropical climate with three main seasons: the hot season (March to May), the rainy season (June to September), and the cool season (October to February). “Cool” and “rainy” are relative terms. The average temperature in Bangkok in December is 77°F (25°C), but it usually feels much hotter because of high humidity, and there are plenty of fine days in the rainy season.

The climate varies according to location. In the mountains of the north the nights can be cold in December and January. In October severe flooding is likely to occur all over Thailand, especially in Bangkok. Areas close to the sea often suffer from high levels of humidity.

Peninsular Thailand has less sharply differentiated seasons. The southwestern coast and hills experience the full force of the southwestern monsoon between May and October, while on the eastern side most rain falls between October and December.

Although there is some ethnic diversity in Thailand, the proportions of which are debatable, over 99 percent of Thai residents have Thai citizenship and most of them identify closely with the country of their birth.

The Thai people are believed to have originated in the Altai mountain region of northern Mongolia 5,000 years ago. They emigrated westward to the Yellow River and later to the mouth of the Huang Ho River and the Chinese province of Szechuan. Attacks by the Tatars and Chinese drove them further south, and by the first century CE they were living in the Yunnan Valley of south central China. In the seventh century CE they began to move southward, settling in what is now Laos and northern Thailand, and gradually absorbed the indigenous Mon and Khmer inhabitants.

Much of the commercial life of the country is in the hands of the Chinese, some of whom have been here since the eighteenth century, have intermarried with Thais, and have adopted Thai ways. There were also waves of Chinese immigrants in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, a minority of whom still practice their own traditions (such as Confucianism). They account for between 11 and 14 percent of the population.

This is the third-largest ethnic group. They practice Islam, speak Malay and Thai, and most live in the four southern provinces of Narathiwat, Pattani, Yala, and Satun. Some have settled in Bangkok and other cities.

Together with the Mon these were the original inhabitants of Thailand who were later almost entirely assimilated by the Thais. However, Khmer (Cambodian) is spoken in the areas bordering Cambodia, and you may meet Cambodians who fled their country during the upheavals of the 1970s and ’80s and did not return.

The Mon have been almost completely assimilated by the Thais, but a few Mon-speaking communities remain in the central plain and some of the provinces.

In the towns and cities you will find a number of Indian shopkeepers, often involved in tailoring and the textile trade. Indians are also employed as guards and night watchmen. Thai criminals are afraid of them because of their dark skins.

There are a number of different peoples (including the Akha, Meo, Karen, Lawa, Lisu, and Hmong) who live mainly in the hills to the north and west. They are thought to number approximately 750,000, and each tribe has its own distinctive customs and languages.

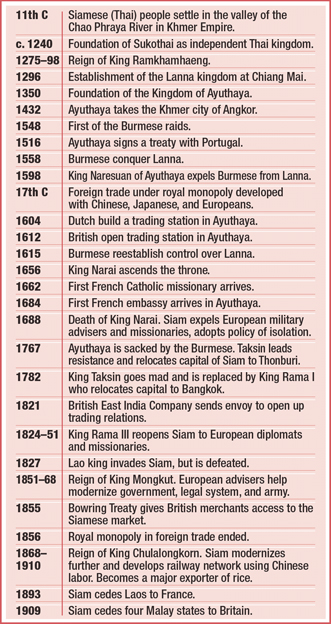

In the seventh century CE the Thais began to move south into what is now Laos and northern Thailand, areas populated by the Khmers and the Mon. There was some conflict with the Khmers but the Mon kingdoms, known as Dvaravati, were more readily assimilated. The first substantial Thai kingdoms to be founded were those of Lanna, or Lannathai, under King Mengrai (1259–1317) in the north, and to its south, Sukhothai (1240–1376), whose most famous leader was King Ramkhamhaeng (1275–98).

Under King Ramkhamhaeng, Sukhothai expanded rapidly and is believed to have occupied territory stretching from Luang Prabang (now in Laos) in the north to Nakhon Si Thammarat in the south, but excluding all lands to the east of the Chao Phraya River. Sukhothai became a great center for Thai art and architecture as well as for Theravada Buddhism. The king, who is credited with adapting the Khmer and Mon alphabets to the requirements of the Thai language, seems to have been a just and benevolent ruler, in contrast to some of the god-kings of the Khmer Empire.

In the time of King Ramkhamhaeng this land of Sukhothai is thriving. There is fish in the water and rice in the fields. The King has hung a bell in the opening of the gate over there. If any commoner has a grievance which sickens his belly and agonizes his heart, he goes and strikes the bell. The King questions the man, examines the case and decides it justly for him.

Inscription in Thai, ascribed to King Ramkhamhaeng

After King Ramkhamhaeng’s death Sukhothai appears to have gone into a slow decline and was eventually incorporated into the Kingdom of Ayuthaya, fifty-five miles north of present-day Bangkok. Ayuthaya had been founded in 1350 by U Thong, a general of Chinese descent, who married into the Thai aristocracy. U Thong and his successors adopted many of the administrative practices of the Khmer.

Ayuthaya consolidated its grip on the former Mon kingdoms, but the Lanna kingdom remained free of Ayuthayan control. In the sixteenth century the Burmese conquered Ayuthaya, which was now coming to be known as Siam, and many of its residents were taken as slaves. There were also incursions by the Khmer at this time. Under King Naresuan (1590–1605) the Burmese were repelled, although they were to remain a constant threat, and large swathes of Cambodia came under Siamese control.

In the early seventeenth century Ayuthaya opened links with the West, sending an embassy to the Hague in 1608, and signing a treaty with Portugal soon after. Thereafter trade developed with other European countries as well as China, India, and Persia, and it became an important commercial center. Foreigners began to settle and establish businesses in the kingdom, the population of which was estimated to be 300,000 or more in the middle of the seventeenth century—larger than London or Paris—and comprised forty different nationalities.

King Narai (1656–88) appointed as his prime minister Constantine Phaulkon, a Greek who had served in the British East India Company. Other foreigners were also given jobs in the King’s service, including the Englishman Samuel White, nicknamed “Siamese” White. Embassies were exchanged with France; the French established a garrison at what is now Bangkok and provided mercenaries for the King’s army. French missionaries tried in vain to convert King Narai.

After King Narai’s death the French garrisons were expelled and there was a backlash against all foreigners. For the next one hundred and fifty years Siam had little contact with the West. There were regular conflicts, in particular with the Burmese, who in 1767 destroyed the capital of Ayuthaya (you can still see the ruins) and caused devastation all over the country.

This was undoubtedly Siam’s darkest hour. However, Phya Taksin, who had come to Ayuthaya to be invested as governor of Kampaengpet Province, managed to escape with five hundred men and set about wresting the country from the Burmese. Taksin was invited to become King and he established a new capital at Thonburi on the opposite bank of the Chao Phraya River to where Bangkok now stands. During his reign (1768–82) he not only succeeded in driving back the Burmese, but also led successful military campaigns in Burma and Laos.

King Taksin became mentally unbalanced, and was forced to abdicate in favor of one of his generals, Chao Phraya Chakri (Rama I), who moved the Siamese capital across the river to Bangkok and founded a royal dynasty that has continued until the present day.

During the first decades of the Chakri dynasty there was further conflict between Siam and her neighbors as well as the Vietnamese. During this time much of western Cambodia was brought under Siamese control, including the former capital of the Khmer Empire, Angkor. The northern Lannathai kingdom, which had at various times been independent or a vassal state, became fully incorporated into Siam.

By the beginning of the third decade of the nineteenth century a new threat to Siamese independence arose in the form of the European imperial powers. The Siamese were eventually forced to concede territory they held in Cambodia and Laos to the French, and four of the southern Malay states to Britain. However, most of the country remained intact, thanks to the skillful diplomacy of successive kings and their officials (see Chapter 4, Monarchy and Military).

The Siamese were open to Western ideas and adopted Western technology with great enthusiasm, and by the beginning of the twentieth century Siam had all the trappings of a modern state. It became a player on the world stage when it supported the Allies in the First World War, sending troops to fight in northern France. After the war the country was to become one of the founding members of the League of Nations.

In 1932 the absolute monarchy came to an end after a bloodless coup—the first of eighteen in the twentieth century—by a group of “Young Turks” led by Pridi Phanamyong and Phraya Phahon Phonpayuhasena. The constitution was changed to make the country a constitutional monarchy, but not long after the army took control and adopted strongly nationalist policies.

During the Second World War Japan invaded Thailand and the government, under Field Marshal Phibul Songkhram, allied itself with Japan—not that it had much choice in the matter. However, the Thai ambassador in Washington refused to declare war on the USA, and a number of prominent Thais were involved in the resistance to the Japanese initiatives, which stood the country in good stead with the USA in the postwar period.

After a brief period of democracy the army retook control of the government, putting Phibul in charge once more. In 1949 a coup d’état by the navy against him failed, but he was eventually ousted by his defense minister, General Sarit, in 1957.

Sarit died in 1963 and his successor, Field Marshal Thanom Kittikachorn, reinstituted limited parliamentary democracy in the late 1960s. However, in 1971 military rule was reimposed. In October 1973, pro-democracy demonstrations by students were dealt with ruthlessly by the military government. The students’ leaders appealed to the King to restore peace, and the prime minister and his deputy were forced into exile.

The King appointed an interim prime minister who supervised the drafting of a new constitution. The following year democratic rule resumed, but the military felt that the apparent instability of the government boded ill for Thailand’s survival at a time when three of its neighbors had fallen to Communism (South Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia), and martial law was reimposed, this time with the King’s backing.

More student demonstrations took place, with many of them joining the Communist insurgency movement that appeared to be gaining strength at the expense of the right-wing administration then in power. In 1977 the same military leaders who had put it in power replaced it with a more democratically minded government led by General Kriangsak Chompriand.

The most recent military coup occurred in 2006, when the prime minister, Thaksin Shinawatra, a business tycoon, was overthrown. Thaksin had become prime minister in 2001 when the party he had founded, Thai Rak Thai (Thais love Thais), won the election and brought in populist policies that reduced rural poverty, established a universal healthcare system, and improved the country’s infrastructure. His government was reelected on a landslide in 2005, but accusations of corruption, authoritarianism, human rights offenses, and various other abuses led to the coup and the subsequent dissolution of the TRT on charges of electoral fraud. Many of its members regrouped as the People’s Power Party (PPP), which after new elections in 2007 formed a government with the support of minority parties.

Thailand’s political divisions have been highlighted in recent years with the emergence of two political movements that have taken to the streets to express their displeasure. The People’s Alliance for Democracy, or PAD, who wear distinctive yellow shirts, is opposed to Thaksin and his followers, and draws its support mainly from the upper- and middle-class residents of Bangkok and the south. The United Front of Democracy against Dictatorship (UDD), who wear red shirts, is pro-Thaksin and was formed after the coup in 2006 to oppose military rule and the influence of the royalist, military, and bureaucratic elites. Much of its support comes from the north, northeast, and poorer sections of society.

Clashes occurred in 2008 when the PAD protested against the installation of Thaksin’s brother-in-law as prime minister by seizing Bangkok Airport. The PPP was dissolved, with some of its members transferring their allegiance to the Democratic Party led by Abhisit Vejjajiva, which became the government. Others formed the Puea Thai Party. Large-scale street protests by the competing political factions broke out intermittently, culminating in 2010 with clashes between the security forces and pro-Thaksin protesters, elements of which were armed, resulting in at least ninety-two deaths and in arson-related damage estimated at US $1.5 billion.

Elections were held in 2011 at which the Puea Thai Party led by Thaksin’s youngest sister, Yinlak (or Yinluck) Shinawatra, gained an absolute majority. Her leadership was almost immediately challenged by large-scale flooding affecting 65 of the 77 provinces and Bangkok itself. The catastrophe caused an estimated US $45 million of economic damage.

Attempts are being made to effect constitutional reform and reconciliation, but clashes still occur between the red shirts and the yellow shirts and the shadow of the exiled Thaksin continues to haunt Thai politics.

Thailand is a constitutional monarchy with a parliament consisting of a 150-member Senate (Woothi Sapha) and a 500-member House of Representatives (Sappha Poothaen Rassadorn). There is universal suffrage, and everyone over the age of seventeen is entitled to vote. Elections are held every four years.

Candidates for the House of Representatives have to be at least twenty-five years old and hold a bachelor’s degree: 375 members are elected on a constituency basis, and the remaining 125 on a proportional basis from party lists The prime minister has to be elected by a majority in the House of Representatives. To become a minister one must be thirty-five or over. Candidates for the Senate must be at least forty and hold a bachelor’s degree.

Normally a party is a loose alliance of individuals clustered around a key figure, not a grouping with a particular ideological persuasion. Party loyalties tend to be fickle, with members ready to change allegiances at the drop of a hat. Most elected governments have been coalitions.

In 2013 the majority party in the National Assembly was the Pheu Thai Party, which governs in coalition with four smaller parties. The Democrats are the main opposition. There are nine other parties in the National Assembly, the largest being the Bhumjaithai Party and the Chartthaipattana Party.

The modern aspect of Bangkok—with its high-rise buildings, its well-stocked shops selling Western goods, its populace dressed in the latest fashions, its polluted air, and infernal traffic jams—may well suggest that this is a city like any other. The international beach resorts may not seem very different from those you find in other countries. But do not be taken in by appearances. Enter one of the many temple compounds around the city, leave the main thoroughfare and go down a back street, or take a long-tailed boat along a canal into the country, and you will discover a different Thailand that seems completely at variance with the hustle and bustle of the city. This is the real Thailand, where tradition is deep-rooted.

Bangkok dominates the country economically, culturally, and politically. Any provincial with ambition aspires to a job there, even though living conditions tend to be much more pleasant elsewhere. Much of industry and all the major companies are based or headquartered there; it accounts for more than half of the national total of telephones and cars—and this is why the city’s traffic jams are so notorious.

Bangkok is the original name for the area, and means “The Village of Wild Plums.” When it became the capital it was given a new name, Krung Thep. This is a shortened version of the official title for the city which is “The City of Celestial Beings, the Great City, the Residence of the Emerald Buddha, the Impregnable City of Indra, the Grand Capital of the World Endowed with Nine Precious Gems, the Happy City Abounding in Enormous Royal Palaces that Resemble the Heavenly Abode where the Reincarnated Gods Reside, a City Given by Indra and Built by Vishnukarm.”

Several of Thailand’s most historical monuments are situated here—notably the Grand Palace and the Temple of the Emerald Buddha, Wat Phra Khao. Bangkok, with its intricate network of canals, was once described as the “Venice of the Orient.” Like Venice it is sinking, but unlike Venice several of the canals have been paved over to make roads. Modern Bangkok is polluted, dirty, and overdeveloped—and its infrastructure is creaking.

Attempts have been made to move the capital away from Bangkok, but have repeatedly failed, for despite the deteriorating living conditions nobody is willing to leave. However, at long last brave attempts have been made to overcome the city’s chronic traffic problems. In 1999 an overhead mass transit railway opened, known as the “Skytrain”; and forty years after the idea was first mooted, an underground railway (subway) opened in 2004, which has interchanges with the Skytrain.

The provinces are very different. No provincial city comes anywhere near Bangkok in size. The largest provincial capital is Nakhon Ratchasima, with around 430,000 residents, while Chiang Mai has only a quarter of a million. But 80 percent of the population lives in the countryside, cultivating the fields as it has over the centuries, though large numbers of country people drift to Bangkok to do seasonal work.

There is a strong sense of community in these places and unless they are on the tourist trail they are less affected by foreign influences. However, it is encouraging to see how the rural communities (including hill tribe communities) are beginning to share in the country’s newfound prosperity.