Mercury has been known for approximately 5,000 years. As mentioned in chapter one, its closeness to the Sun makes it difficult to observe from Earth. Moreover, the Hubble Space Telescope and other Earth-orbiting instruments are too sensitive to be pointed that close to the Sun. Astronomers have used radar to study Mercury by sending radio waves toward the planet and detecting and measuring the waves that bounce back.

Unlike the other planets, Mercury has no significant atmosphere, or surrounding layers of gases. At Mercury’s surface, the pressure—the force exerted by the atmosphere—is less than one-trillionth that at Earth’s surface. Mercury’s extremely thin layer of gases includes atoms of helium, hydrogen, oxygen, and sodium. The gases do not remain near the planet long before the Sun’s heat blasts them away. They are replenished partly by the solar wind, the flow of charged particles from the Sun. Other gases come from asteroids and comets and from the planet’s surface.

Mercury has a magnetic field similar in form to Earth’s. However, Mercury’s magnetic field is much weaker, at only about 1 percent the strength of Earth’s.

Temperatures on Mercury vary widely. Its closeness to the Sun makes it a broiling-hot world by day, with daytime surface temperatures exceeding 800 °F (430 °C) at parts of the planet. Because Mercury lacks a thick atmosphere to trap heat, however, the planet cools greatly at night. The temperature can drop to about − 300 °F (- 180 °C) just before dawn. The average surface temperature is about 332 °F (167 °C).

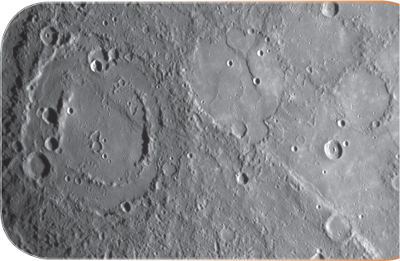

Mercury’s surface is dry and rocky. Much of it is heavily cratered, somewhat like Earth’s Moon. Impact craters form when meteorites, asteroids, or comets crash into a rocky planet or similar body, scarring the surface. Planetary scientists can estimate the age of a surface by the number of impact craters on it. In general, the more craters a surface has, the older it is. Mercury’s heavily cratered surfaces are probably ancient.

Between the planet’s heavily cratered regions are areas of flat and gently rolling plains with fewer craters. Elsewhere there are smooth, flat plains with very few craters. Volcanic lava flows probably smoothed the surfaces of these plains.

A double-ringed crater on Mercury appears at left in an image taken by the Messenger spacecraft on Jan. 14, 2008. After the crater formed, it was apparently filled in with smooth plains material, perhaps volcanic lava. A long scarp, or cliff, runs along part of its rim and also cuts through another crater at bottom right. NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington

Impacts have formed craters on Mercury of all different sizes. The planet also has several huge impact basins. Each of these basins has multiple rings in a bull’s-eye pattern. The most prominent impact basin, named Caloris, measures about 900 miles (1,550 kilometers) across. Caloris is one of the youngest and largest impact features in the solar system. Along the rim of the basin, mountains rise to heights of nearly 1.9 miles (3 kilometers). On the opposite side of the planet from Caloris is an area of strange hilly terrain. Planetary scientists think it resulted from the same impact that created the Caloris basin. The crash caused seismic waves (vibrations) to ripple through the planet. The waves came to a focus on the part of Mercury opposite the crash site, where they warped the terrain.

Hundreds of long, steep cliffs called scarps also mark the planet’s surface. Planetary scientists believe that, at some point in Mercury’s history, part of the planet’s interior (the mantle) began to cool and shrink. As the planet shrank, the crust buckled and cracked, forming the many scarps. Mercury may even still be shrinking.

The side of Mercury directly opposite the Caloris impact basin has an area of oddly contorted and hilly terrain, which appears in an image taken by the Mariner 10 spacecraft. Seismic waves from the impact that formed Caloris traveled around the planet and warped the terrain on the opposite side. The smooth interior of the large crater at left indicates that its floor filled in sometime after the impact. NASA/JPL

Like Earth, Mercury has three separate layers: a metallic core at the center, a middle rocky layer called a mantle, and a thin rocky crust. In both planets, the core is made mostly of iron. However, Mercury’s core is proportionally much larger than Earth’s. The core takes up about 42 percent of Mercury’s volume, compared with only about 16 percent for Earth. This accounts for Mercury’s great density.

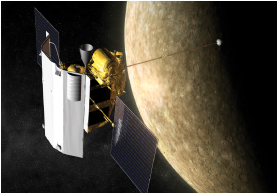

NASA technicians carefully lift the Messenger spacecraft in order to move it to a prelaunch testing stand. NASA

The planet’s nearness to the Sun presents challenges for space probes, which must contend with great heat and the enormous pull of the Sun’s gravity. A spacecraft needs a lot of energy in order to enter into orbit around Mercury.

Much of the information known about Mercury comes from images and data transmitted by the Mariner 10 spacecraft, the first to visit the planet. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) launched the craft in November 1973 toward Venus for the initial leg of its mission. Mariner 10 became the first spacecraft to use a “gravity assist,” drawing on Venus’s gravitational field to boost its speed and divert its course toward Mercury. It captured the first close-up photographs of Mercury in March 1974. Mariner 10 encountered Mercury twice more. Its final and closest pass, in March 1975, brought it to within 200 miles (325 kilometers) of the surface.

Messenger was launched on Aug. 3, 2004, by a Delta II rocket from Cape Canaveral, Fla. Its first flybys were of Earth, on Aug. 2, 2005, and of Venus, on Oct. 24, 2006, and June 5, 2007. Flybys of Mercury happened on Jan. 14 and Oct. 6, 2008, and on Sept. 29, 2009. A fourth encounter began early in 2011, when a thruster maneuver inserted Messenger into orbit around Mercury where it will study the planet closely for a year, using sophisticated equipment. The spacecraft’s nominal mission will end in 2012.

The Messenger mission was designed to answer a number of major scientific questions. Among them are: Why is Mercury so dense? What is the geologic history of Mercury? What is the nature of Mercury’s magnetic field? And what is the structure of Mercury’s core?

Artist’s impression of the Messenger spacecraft near the planet Mercury. NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington

Messenger has already made a number of discoveries. During its first flyby of Mercury, Messenger revealed that the planet’s craters are only half as deep as those of the Moon. The Caloris impact basin was found to have evidence of volcanic vents. Messenger also discovered huge cliffs at the top of crustal faults called lobate scarps. These structures indicate that the planet, as it cooled early in its history, shrank by a third more than what had previously been believed.

Mariner 10’s orbital path allowed it to photograph only one side of Mercury. Low-resolution radar images taken from Earth suggested that the planet’s other hemisphere has broadly similar terrain; this was confirmed when the Messenger spacecraft photographed areas of the surface unseen by Mariner. NASA launched Messenger, only the second spacecraft ever sent to Mercury, in 2004. It was designed to be the first probe to orbit the planet, getting gravity assists during a flyby of Earth, two flybys of Venus, and three flybys of Mercury.