Latin America – new pastures

UNTIL THE 1990S the prospects in Latin America had not made a big impression on HSBC. ‘The Group undertakes very little business: mainly trade finance and capital markets activities, both within tightly controlled country limits,’ observed the 1995 Group Strategic Review. ‘No change is envisaged in this limited strategy.’1 But only two years later this situation was transformed with the investment of almost $2 billion in Brazil, Argentina, Mexico and Peru. Each country had its own particular story, prompting Michael Geoghegan, head of the new Brazilian subsidiary, to describe their conjunction in 1997 as ‘just a lot of luck and a lot of interest’.2 But together these acquisitions constituted a major strategic departure, filling (as Institutional Investor put it) ‘a gaping hole in the Group’s global distribution network’.3

Doing the spade work

With the integration of Midland Bank largely completed, Marine Midland performing well and the Group financial performance ‘sound on all fronts’, John Bond told the Group Executive Committee (GEC) in December 1996 that ‘we are ready for new challenges’.4 The interest in Latin America did not come out of the blue. ‘Willie Purves was very much more aware than anybody else about Latin America,’ recalled Geoghegan. ‘He knew Chile and Brazil. He even went on honeymoon in the region.’5 In the mid-1990s other international banks, especially the Spanish, boosted their presence there, while Citibank and BankBoston also had significant regional operations. ‘We knew that we wanted to expand in Latin America,’ reflected Keith Whitson. But ‘it isn’t just a question of going out and buying something. You really have to wait until a suitable opportunity arises. I did a lot of spade work talking to the finance ministers and central bank governors.’6

HSBC was by no means unknown in the area.7 The Midland acquisition had brought a significant shareholding in Argentina’s Banco Roberts, branches in Panama and representative offices in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Venezuela; while Hongkong Bank had its own two branches in Chile and an office in Argentina.8 Responsibility for all these various entities came under Midland International in London from the mid-1990s, and then were managed by Geoghegan. ‘When we bought Midland Bank, it had something like $4 billion of assets in Latin America,’ Bond explained to Euromoney in 1998. These blocked funds, largely in the form of Brady bonds backed by US Treasury bonds, were legacies of the region’s 1980s debt crisis. ‘Rather than do debt-equity swaps into canning plants and industrial projects we didn’t know much about, we decided to do debt-equity swaps into positions in banks, a business which we did know about.’9 In Chile, for example, the two Hongkong Bank branches, plus $15 million of blocked funds, were exchanged for an 8.7 per cent shareholding in Banco O’Higgins in 1993.10 It was a similar story in Peru, where blocked funds were used to purchase a 10 per cent stake in Banco del Sur in 1997.11

Mexico was also on the radar, with proposals to take stakes in banks there on the table from 1993 onwards. After one such proposal was dropped in 1994, the GEC noted that ‘consideration will be given to expanding the current Group presence in Mexico in recognition of the importance of Mexico’s economy, which represents 40 per cent of the Latin American market and is growing’.12 But by the end of the year the situation was very different after devaluation of the Mexican peso had led to a stock market crash, soaring inflation, high interest rates and recession. The ‘tequila crisis’ left Mexico’s banks awash with problem loans − and Banca Serfin, the third-largest, in dire trouble. It was rescued by the government and, on a visit to London in March 1996, President Zedillo told Purves that an HSBC investment in the bank would be welcomed.13 Negotiations followed – despite Purves questioning at one point whether HSBC had ‘the necessary Mexican expertise’.14 Approval for a 19.9 per cent shareholding in Serfin was approved by the Holdings board in late November 1996 and announced, after due diligence, in March 1997.15

Brazil: getting to know Banco Bamerindus

Hard on the heels of the Mexican investment was a major foray into Brazil. As Latin America’s largest and most populous country, with abundant natural resources, a sizeable domestic market and vibrant private sector, Brazil had plenty of potential. Purves had long relished the prospect of a substantial HSBC presence there, and at last in 1997 this became possible.16

The story went back about a quarter of a century. Brazil had been an extravagant borrower from the international banking system in the mid-1970s and both Hongkong Bank and Midland Bank had established representative offices in the country in 1976; when Brazil defaulted in 1983, Midland Bank was a big creditor and became the holder of substantial amounts of blocked funds in the country.17 The highly regulated Brazilian banking sector restricted access by foreign banks, turning down applications by both Hongkong Bank and Midland to convert their offices into full branches, but both banks found Brazilian partners for modest joint ventures. These ventures were overseen by country manager Frank Lawson, who acted as HSBC’s local eyes and ears and began to lobby for HSBC to develop a more substantial presence in Brazil.18

HSBC’s Brazil Strategic Plan 1993–1995 highlighted the progress with economic reforms made since 1989 by the administration of President Collor, though noting that ‘Brazil has disappointed so often in the past’.19 Although the plan recommended immediate withdrawal from Hongkong Bank’s joint venture, because of the ‘considerable “deep pocket” risks’, it was far from negative about other prospects − noting the possibility of the relaxation of the ban on foreign bank shareholdings in Brazilian banks and the potential deployment of HSBC’s blocked funds. It recommended ‘seeking out a respectable major Brazilian bank for a minority investment and alliance, in line with the approach being adopted in Chile and Argentina’.20

Building work at the Palacio Avenida, Curitiba, prior to it becoming the headquarters of the Banco Bamerindus do Brasil, 1960.

Four potential partners were duly identified, and Banco Bamerindus do Brasil was rated ‘the first choice’ (‘only’ jotted John Bond on his copy).21 Founded in 1943, Bamerindus had become the fifth-largest Brazilian bank through a series of acquisitions. Since 1952 it had been controlled by the Vieira family group of companies, though there were also many thousands of small shareholders. Senator Vieira, chairman of the family group, was himself a former Minister of Industry and Commerce and a close ally of new President Fernando Cardoso.22 ‘Strong in trade finance, treasury funds management and capital markets,’ noted the strategic plan. ‘Culture is very much grass roots and no frills; headquarters in Curitiba, the state capital of Parana, 450 km south of São Paulo, although major presence in São Paulo. Family group’s overall resources and performance has been strained by recent strategy to expand banking market share and diversify its investments; apparently a foreign partner with capital injection may be welcomed. Management know Midland well and recently met HSBC management in HK; great interest in Asian business and investment.’23 Bamerindus had, in fact, been Midland’s partner in its joint ventures in Brazil in the 1970s and 1980s, and the relationship had been positive. In May 1994, it was decided to sell all other interests in Brazil and to invest in Bamerindus. The investment took the form of a $56 million capital note that, at some future date when legislation permitted, would be convertible into 6.14 per cent of the bank’s shares. Bamerindus’s management welcomed the renewed ‘alliance’.24

Brazil: acquiring Banco Bamerindus

A banking crisis hit Brazil in November 1995, with runs at several banks culminating in Banco Nacional, Brazil’s seventh-largest private bank, being taken over or ‘intervened’ by the central bank. ‘The country has 246 banks, many with few customers, and several large banks are weakened by family rather than professional management,’ commented the Financial Times. ‘Further banking problems are expected.’25 Rumour swirled around Bamerindus, prompting a presidential decree allowing the conversion of Midland’s investment into equity in order to strengthen the bank’s capital, a development interpreted as ‘opening the door to more foreign ownership in the future’.26 But Bamerindus’s plight continued with higher borrowing costs and falling profits.27 In March 1996, Keith Whitson reported that Bamerindus had recently lost 30 per cent of deposits and was going through ‘a testing time’.28 The bank’s deteriorating condition prompted Brazil’s central bank to send in a forty-strong audit team to carry out a branch-by-branch review. It concluded that the bank was potentially sound, but around 400 branches − a third of its network − were unprofitable.29

That October, with losses running at $3 million a day, the central bank informed Purves that it intended to intervene at Bamerindus, by recapitalising the bank with a $2.1 billion cash injection and eliminating the Vieira group and other existing shareholdings.30 But this would only be the first stage of a rescue, since Bamerindus urgently needed a new owner and management to turn the business around. Despite being a foreign bank, HSBC was the obvious candidate. In November, the Holdings board learned that the Brazilian finance minister had confirmed that Bamerindus was ‘too big to be allowed to fail’ and that HSBC was being offered the opportunity to buy ‘assets and liabilities at choice’. The board paper summarised the pros and cons: ‘The investment opportunity is unique but the challenge in a foreign language country, where there is little prior Group knowledge, cannot be underestimated. With skilful management and strengthened controls, this opportunity will give the HSBC Group the largest foreign banking franchise in Brazil as well as the region as a whole, thereby ideally placing it to capitalise on the projected growth in the Mercosur [the trading bloc that included Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay].’31

Banco Bamerindus do Brasil’s attractions were considerable: 1,200 branches, 25,000 staff and $6.5 billion of assets. Its 250,000 medium-sized business borrowers and 2.5 million depositors generated national market shares of 8.3 per cent of loans and 5.7 per cent of deposits. ‘The bank is considered to be one of the more efficient deliverers of services in the local market,’ stated an HSBC review, noting that it had invested heavily in technology and had an extensive ATM network. It was Brazil’s second-largest trade finance bank, the majority shareholder in Brazil’s fourth-largest insurance company, and there were also leasing and asset management subsidiaries. Why had things gone wrong? Factors identified by the review included dramatically reduced inflation eroding previously high net interest margins; over-aggressive branch expansion for political benefits; ‘disastrous’ treasury management; and loss of depositor confidence, resulting in a shrinking deposit base and reliance for funding on the central bank at a penal rate of 35 per cent.

Purves was keen to proceed and, appreciating that such an acquisition would need dedicated management to succeed, asked Mike Geoghegan to commit to a long-term posting to Brazil to take charge. Realising that such a posting was not without its challenges, Purves also felt obliged to remind Geoghegan of the bank’s policy on staff kidnapping − HSBC would look after the widow and children. Undeterred, Geoghegan quickly began consulting with the central bank to formulate an acquisition plan. The first step would be the creation of a ‘New Bank’, Banco HSBC Bamerindus, a wholly-owned HSBC Brazilian subsidiary that would be ring-fenced from the ‘Old Bank’. The plans were explained to the Holdings board: ‘It is envisaged that over a weekend, the central bank will appoint an Interventor of Bamerindus, and at the same time selected banking assets and liabilities and financial services businesses will be purchased by the “New Bank”. The “Old Bank” will comprise identified non-performing third party loans. All remaining Bamerindus group companies and personal assets of the major shareholders and executive officers of the group will be seized and all companies thereafter will be run by the Interventor for the benefit of creditors.’ The senior management responsible for Bamerindus’s predicament would, at central bank insistence, be removed immediately and replaced by HSBC Group executives seconded from all over the world. The deputy CEO would be Brazilian and the board would include prominent Brazilians as well as non-resident Group executives.32 Over the winter of 1996–7, Geoghegan shuttled between London and Brazil to work out the details of the deal in secret talks with the central bank and finance ministry. Finally, on 28 February, Geoghegan got a call confirming that the deal was on and setting Thursday, 27 March 1997, just before the Easter holiday weekend, as intervention day.33 The agreed terms committed HSBC to injecting $1 billion of capital, for which it would acquire assets and liabilities to that amount, and also paying $360 million for goodwill and other intangible assets − but to be paid a matching amount as a restructuring fee.34

In the meantime, Geoghegan put together a team of fifty International Officers (IOs) and other Group executives to take control of Bamerindus. ‘It was all done undercover,’ he recalled. ‘This was politically a very new thing. It was the first time a foreign bank had bought a big Brazilian bank. We came under different names and different companies.’35 ‘I got this weird phone call from my boss,’ remembered Rumi Contractor, an IT expert at Midland International, ‘saying “I have just had a conversation with Mike Geoghegan. He is putting together a small team of people to go into a place.” I said, “Where?” He said, “I can’t tell you yet.” Then, “Would you be interested?” I said, “Yes.”’ And Contractor went on, ‘Roll forward a couple of weeks, I landed in São Paulo. They hired a whole hotel for us. People kind of drifted in over three or four days. In those days cell phones were really rare. We were all given these cell phones and it made us feel that we were in this 007 movie. We couldn’t go out on our own. A lot of security guys.’36 The HSBC team moved to Curitiba on Wednesday, 26 March, while Geoghegan flew to Brasilia, hoping to sign the final deal. He returned at 3 a.m. and announced to the drowsy IOs in the hotel bar: ‘It’s done!’37 ‘We had,’ he remembered, ‘three days to open the bank on the Monday morning or the contract could have been rescinded. We knew nothing about the bank. We knew nothing about the computer systems. It was hairy stuff.’38 It was time for the IO system to prove its mettle.

‘In the morning, like schoolchildren, we were bundled into these mini-vans and dropped off in different parts of the city with armed guards and our interpreters,’ recalled Contractor. Geoghegan recollected that ‘when you went into the management offices it reminded me a bit of what the Titanic must have looked like. Chairs were turned upside down. Coffee cups were still sitting on the tables. It was like a period of time had come to an end.’ The HSBC team set to work in a very structured way with checklists and timetables to impose order on this very fluid situation. ‘So those four days, I don’t remember sleeping,’ noted Contractor, almost fondly. ‘I remember this adrenalin pumping through all of us. Monday comes, we open the bank doors, we are now operating as HSBC. Most people will never be involved in a deal like that. It was truly one of a kind.’

Brazil: turning around Bamerindus

By a stroke of luck, the Brazilian Grand Prix was taking place over that Easter weekend, with local hero Rubens Barrichello driving for the Stewart–Ford F1 Racing Team with HSBC sponsorship and branding. Purves recollected that Geoghegan got Barrichello to record a television advertisement ‘which said, roughly, “You don’t know who HSBC are, but I do, I drive their car. They are a great bank, you bank with them.” That played all weekend when the Grand Prix was on.’39

Despite the advert and the intense work behind the scenes, there was, inevitably, a run on the bank as soon as it opened. Geoghegan recalled, ‘So I walked branch to branch. We took the TV cameras with us. You saw us walking through the branches, talking to the customers, and that was televised across Brazil and it was a big event. I think the first few hours we were down about 40 or 50 million of deposits going out. By the end of the day, I think, we ended up about 70 million in deposits and from then on it worked quite well.’40 ‘A shed load of problems,’ was how Contractor described the opening on Easter Monday, 31 March. ‘But the beauty was that because the bank had been stuttering for a very long time, actually the clientele were very happy that HSBC was on board. From their perspective, a global organisation, a foreign multinational bank, coming into Brazil for the first time, meant that a big local bank would not fail.’41

Geoghegan would later summarise the attitude of Bamerindus staff to HSBC’s arrival as a mixture of fear and joy. ‘Fear because they did not know anything about HSBC, and joy because they thought they would have a job or career in the future.’42 The immediate language issues were helped by ‘shadow people’ from the Brazil offices of global accountants KPMG and Price Waterhouse, who acted not only as translators but also as intermediaries. Geoghegan and the others were tutored in Portuguese while they got on with the job. ‘I had a Portuguese teacher and I attended an intensive course,’ recollected Geoghegan. ‘There was a difficult security situation and we had to have bodyguards all the time. The previous owner of the bank had allegedly made serious threats that had to be managed. I was learning Portuguese and there were bodyguards outside the door. It was an interesting time.’

While older Bamerindus staff were anxious, one of the HSBC team remembered that some of the younger people were very excited as the acquisition would prompt promotions from among existing staff to fill management positions. However, Geoghegan also needed an immediate infusion of experienced Brazilian bankers and found them working in Citibank’s Brazil operation. With Bond’s blessing, Geoghegan broke the unwritten HSBC rule about not hiring from Citibank and brought them into the fold.43 Emilson Alonso, one of the bankers brought in from Citi, stressed the challenge of closing the gap between HSBC Group standards and ‘the way business was run in Brazil, and the way the local team understood it. The cash was very poorly managed. There was no risk management there, nothing. So we had to establish these basic standards till we started operating and started making money, because the bank was losing money.’44 Progress towards bringing HSBC Bamerindus into line with Group practices was reviewed by the new board which met for the first time in May. The directors found the set of reports ‘relatively encouraging’ but acknowledged ‘the enormity of the tasks’ faced by management. ‘Bamerindus had been run down in the past few years, premises looked tired and were often poorly sited and were only partially occupied,’ it was noted. ‘A competent local management cadre would have to be rebuilt.’45 ‘We made it very clear right from the beginning that they were part of the HSBC Group,’ said Geoghegan. ‘We expected them to keep the standards and the integrity, the culture of HSBC. They adapted very quickly.’46

A progress review as the first anniversary of the acquisition approached was guardedly upbeat: ‘The cultural differences evidenced in the contrast between HSBC and local practices will inevitably require great effort and time to realign local practices to Group standards. The level of spoken English within HSBC Bamerindus has meant that translating the ethos of Group values, and communicating these, has been challenging. Nevertheless, much progress has been made. A remarkable turn round.’47 That turn round was largely attributable to Geoghegan’s energetic and dedicated management but there was no let-up in the challenges facing him. As expected, the Vieira shareholders disputed the legitimacy of the central bank intervention and HSBC’s ownership of Bamerindus, claims that were ‘robustly defended’.48 The Brazilian Senate launched an inquiry into the bank acquisitions of 1995–7, investigating accusations of inside information from the central bank, which Geoghegan contested in televised evidence.49 A financial crisis in January 1999 led Brazil to float the real, which plunged 40 per cent against the dollar.50 However, the economic uncertainty reinforced public perceptions that HSBC Bamerindus was a ‘strong bank’, generating a surge in deposits − funds that in turn were lent to the government at high rates of interest, producing ‘exceptional’ treasury profits in 1999.51

The bank’s sound financial performance was maintained in the following years, winning the accolade ‘the most profitable foreign bank in Brazil’ in a 2001 industry survey.52 Cost-cutting was part of the solution, and the workforce was reduced by 4,000 to 21,000.53 Some 300 branches were closed in the first two years, but most of the remaining 900 branches were refurbished over the same period.54 Increasing income was the other side of the equation, and this was helped through the growing focus on personal financial services, with rapid advances in the number of personal banking customers – including opening the first Premier centres from 1998 − and rising rates of product cross-selling.55 The integration of the Brazilian subsidiaries of Republic and CCF also helped to boost the private and commercial banking operations. And year after year, throughout these tumultuous times, Bamerindus continued to conduct its renowned Christmas carol concert from the bank’s headquarters in Curitiba, invariably attended by an astounding 150,000 people.56

Argentina: acquiring Banco Roberts

Within weeks of taking over Bamerindus, HSBC spotted another potential Latin American acquisition – Argentina’s Banco Roberts.

As in Brazil, HSBC was already a minority shareholder in the bank and working relationships were good. The contact had begun with Midland Bank’s very active Buenos Aires representative office, which worked with Argentinian exporters, one of whose managers persuaded Midland that Banco Roberts would make a good local partner.57 The initial investment came in 1988 when Midland paid $10.4 million from its blocked funds in the country for a 29.9 per cent shareholding in Roberts. Founded in 1908, Banco Roberts was by then the country’s sixth-largest bank with some thirty-three branches, mostly in Buenos Aires or its suburbs, and $1.1 billion of assets.58 However, a move into Argentina was not for the faint-hearted – the country had a chequered history of military rule, fiscal irresponsibility and hyperinflation. Financial stabilisation was achieved by the adoption in 1991 of the unrestricted convertibility of the Argentine peso into the US dollar at a fixed rate of one-to-one, with the Argentine central bank backing every peso in circulation with a dollar in its reserves. The resulting stable currency, low inflation and strong economic growth encouraged HSBC’s interest.

The Argentina Strategic Plan 1993–1995 envisaged continuation of the ‘close strategic alliance’ between HSBC and Banco Roberts.59 To this end it supported a $30 million capital increase by Banco Roberts, to which Midland subscribed $10 million, doubling its investment.60 Mexico’s December 1994 tequila crisis triggered capital flight from Latin American countries and a severe run on the Argentinian banking system.61 The president of Banco Roberts appealed to Purves for assistance and HSBC made available a crucial $100-million standby credit line, which, recalled Antonio Losada, then working for Banco Roberts, was very much appreciated.62 The crisis led to bank consolidation in Argentina, including Banco Roberts’s acquisition of Banco Popular Argentino in January 1996. HSBC injected an additional $11 million to maintain its shareholding, further strengthening the relationship.63 By 1997 Banco Roberts had sixty branches and $2.9 billion of assets.64

In April 1997, Roberts SA de Inversiones (RSAI), the family financial services company that owned 70.1 per cent of Banco Roberts, received an unsolicited acquisition approach from GE Capital.65 RSAI had promised that HSBC should have an opportunity to bid should it receive an offer from elsewhere and Enrique Ruete, RSAI’s chief executive, flew to London for confidential discussions with Bond. By then Argentina had rebounded from its tequila crisis troubles, and Bond noted that the economy was now ‘relatively well-managed’ with 6 per cent growth anticipated in 1997 and following years.66 In the two decades prior to the stabilisation of the peso in 1991, the country had experienced such economic and political turmoil that the provision of retail financial services had all but disappeared, leaving only the nimble and strong surviving in the corporate market.67 The result was that Argentina, with a GDP per capita of $8,000 − among Latin America’s highest − was significantly ‘under-banked’, with a deposits-to-GDP ratio of 16 per cent compared with Brazil’s 28 per cent and Chile’s 53 per cent. HSBC concluded that the Argentine banking industry had ‘scope for considerable growth’ and that ‘Argentina today is one of the last significant under-developed financial markets in the world’.68

RSAI’s portfolio of financial services interests comprised Banco Roberts plus minority holdings in four affiliated joint venture insurance companies and an asset management company. This portfolio of disparate interests made it tricky to value, with $688 million being adopted as ‘most appropriate’, 2.7 times net asset value.69 ‘On the face of it this is a very high price both in absolute terms and relative to HSBC’s previous acquisitions,’ observed a confidential corporate communications briefing note. ‘In particular, the acquisition would appear to break with HSBC’s previous strategy of making opportunistic, or at the very least low cost, acquisitions of distressed or troubled situations.’ Crucially, though, the acquisition of RSAI had a variety of ‘particular attractions’: HSBC’s detailed knowledge of Banco Roberts and its management reduced ‘the risk of the transaction when compared to other potential acquisitions’; the competence of the local management limited calls on Group resources ‘at a time when they are already stretched’; the breadth of RSAI’s activities provided opportunities for cross-selling financial products; rapidly growing economic links between Brazil and Argentina as well as the recent acquisition of Bamerindus added to ‘the logic of an increased Group presence in Argentina’; and Banco Roberts’s previous year’s earnings were depressed by exceptional provisions associated with Argentina’s recent banking crisis.70 ‘In short’, concluded the note, ‘the price HSBC is paying is a fair one, is consistent with our return requirements and reflects our belief in the significant future growth opportunities which exist both for the country, the Region and, most importantly, for the businesses we are now acquiring.’71

A leak in the Argentine press about the discussions prompted a hurried announcement of the proposed acquisition on 30 May 1997.72 The news was reported to be well received in Argentina, despite the fact that four of the country’s seven largest banks would now be foreign-owned. The acquisition was completed in August 1997, $590 million being paid up-front with the remainder dependent on performance.73 Enrique Ruete became chairman of HSBC Banco Roberts and Michael Smith, a high-calibre career HSBC banker, then deputy country head in Malaysia, was parachuted in as chief executive.74

Argentina: dealing with Banco Roberts

HSBC’s principal motive for the acquisition for RSAI had been to secure Banco Roberts, but in drawing up a post-acquisition plan for Argentina it became obvious that the non-banking operations in which HSBC now held significant minority shareholdings had a bigger customer base than the bank itself.75 To maximise this strong competitive advantage the plan envisaged capitalising on the existing sales force of these non-banking ventures – primarily the insurance subsidiaries − especially as this provided ‘an attractive alternative to a branch expansion programme, which much of the competition is pursuing’.76 ‘This potential can be realised only if HSBC Roberts Group becomes an integrated financial services organisation,’ Smith told senior colleagues.77 In practice this meant securing majority ownership of the associates, and a buyout of most of the joint venture partners followed.78

Getting a grip on HSBC Roberts proved considerably more difficult than was anticipated, particularly as only half-a-dozen IOs were dispatched to support Smith − reflecting the fact it was a profitable business in which, noted the Group Audit Report for 1997, ‘the quality of the management is generally good’.79 Yet as early as January 1998 Smith’s reports to head office revealed that ‘a great deal remains to be tackled in the Roberts Group’.80 By October, HSBC Roberts was showing a significant loss for the year and concern was mounting. A deteriorating financial and economic situation did not help matters, especially after Russia’s default on government debt in August 1998 had prompted capital flight from emerging markets including Argentina. Despite the dollar peg, investors were becoming concerned about the level of government debt, which rose from 29 per cent of GDP in 1993 to 41 per cent in 1998.81 Argentina slid into recession in the second half of 1998, with rising unemployment, a growing budget deficit and yet more government borrowing. It was, observed Whitson, ‘a particularly difficult year in Argentina’, with HSBC Roberts making a loss of $22 million.82

The business staged a turn round in 1999, generating a profit of $26 million, which increased to $57 million for 2000.83 Strong performances by the insurance and fund management entities were the key factors but, with close attention being paid to costs, the banking business was back in the black.84 At the request of the Argentine central bank, in April 1999 HSBC Bank Argentina (as it was renamed in March 1999) took over the failing Banco de Mendoza, acquiring an additional eight branches and deposits.85 Republic’s corporate banking operations in Argentina were absorbed in 2000, though Republic’s 8,000 private banking customers in the country were assigned to a regional private banking operation based in Chile.86 With these acquisitions and the consolidation of the insurance and fund management companies, the business by 2000 comprised 160 offices in Argentina, of which sixty-seven were bank branches, and 6,000 employees.87 That October it was named Argentina’s ‘Number One Business Bank’ by Mercado magazine.88

HSBC Bank Argentina’s progress was made against a background of continuing recession and mounting financial problems. A growing current account deficit, exacerbated by Brazil’s January 1999 devaluation, was accompanied by fiscal deficits and further government borrowing; the debt-to-GDP ratio hit 64 per cent in 2001. Government spending cuts were met by strikes and protests, some of which targeted foreign banks. Personal security was also deteriorating. In November 1999 chief executive Mike Smith was ambushed by armed men whilst driving at night in Buenos Aires, and shot in the leg.89 The episode led to enhanced security measures for staff in Argentina and a review of global policy on security and ransom demands.90

Against a continuing bleak outlook, in July 2001 Bert McPhee, Group general manager, Credit and Risk, drew up several ‘what if’ scenarios, giving some indication of the potential hit to the Group in the event of any debt rescheduling and devaluation.91 His ‘best “guesstimate”’ was that rescheduling would cost the bank $250 million, while devaluation could cost between $250 million and $1 billion, depending on the severity of the knock-on effect. By November, HSBC had become convinced that default or rescheduling of the government’s outstanding debt was unavoidable. ‘The impact on the Group of the current situation in Argentina is difficult to determine with any precision given the state of crisis in the country,’ stated a review for the Holdings board. ‘Clearly, however, there is a material deterioration in our financial investment in the country.’ Provisions of $300–500 million were made against possible losses − around half the capital that had been committed to Argentina.92

By the end of November a full-blown bank run was under way. On 1 December President Fernando de la Rúa imposed a $1,000 a month limit on bank withdrawals and banned the transfer of money abroad − a series of financial restrictions known as the corralito. Argentines turned for safety to the foreign banks, which experienced a flood of new business. In the two weeks following the corralito, HSBC Bank Argentina opened 70,000 new accounts, giving rise to the hope that ‘when the crisis subsides the Group will end up with a strong customer base’.93 But the crisis had a long way to go yet. The restrictions on access to bank deposits triggered furious mass public protests which turned violent, prompting the resignation of the economy minister and the declaration of a state of siege by the government on 19 December. Rioting continued the next day, with the death toll rising to twenty-eight, and by evening de la Rua was gone.

A week later, in the ensuing political chaos, Argentina duly suspended payments on its public debt, the largest sovereign default in history.94 The new President, Eduardo Duhalde, was sworn in on 2 January 2002, and that day Smith telephoned head office to warn that devaluation was imminent. ‘Political situation getting worse and uglier as media/government now blaming foreign banks,’ Douglas Flint reported to Bond, Whitson and McPhee.95 Duhalde unveiled his new economic plan on 6 January. Condemning the ‘immoral’ market reforms of the 1990s, he announced the abandonment of one-to-one dollar–peso convertibility and subsequently a new ‘official’ rate of 1.40 pesos to the dollar, a 29 per cent devaluation; but the market rate immediately plunged to two pesos to the dollar and by June a dollar bought four pesos.96

Banks were directly affected by related measures concerning deposits and outstanding loans. It was stipulated that dollar-denominated deposits (as most were) were to be repaid by banks in dollars. But borrowers in dollars of sums under $100,000 would repay in pesos at the exchange rate of onefor-one. Since the peso had just been officially devalued to 1.40 to the dollar, the banks would suffer huge losses. On 8 January, Smith put Bond in the picture:

The situation here continues to be completely chaotic, with rules and regulations changing by the minute. We are very concerned at the direction being taken by Duhalde’s government which appears to be purely populist, xenophobic and utterly out of touch with the real world. The latest devaluation scheme will cost the banking system $5.7 billion. The government is still saying that deposits in US dollars will remain. They are therefore fundamentally adjusting the balance sheets of the banks and are expecting the pain to be taken by them. If the peso goes to 2 (which is likely) the system will lose $10 billion – half of which will be for the account of the foreign banks. I have made it clear to the government that they cannot expect foreign companies to take such losses purely because they are politically unwilling to distribute the pain to the depositors and general population. However the trend appears to be taking Argentina to a closed economy and to encourage the foreign investors to leave. The press have also been stirred up and are full of anti-bank and anti-multinational rhetoric.97

What did HSBC stand to lose? The Economist subsequently cited estimates that the bank might have to take a charge of $1 billion, but Smith’s estimates to Bond were a good deal higher.98 ‘Running the numbers for HSBC of a devaluation to 2 in very broad terms and with the existing political climate, we have the following results’:

|

Loss of say 30% of loan book |

$600m |

|

Loss of say 50% of bond portfolio |

$500m |

|

Loss on currency |

$250m |

|

Currency mismatch |

$200m |

|

$1,550m |

Smith summed up the situation: ‘Considering the capital of HSBC Bank Argentina is approximately $300m, we have to carefully consider whether it is worth losing over 5 x book. If the current political situation does not change we need to consider whether it would be better to just walk away.’99

Next day, Bond outlined developments in Argentina to Sir Howard Davies, chairman of the Financial Services Authority, HSBC’s regulator:

Recent measures have caused us major concerns. For example, our liquidity reserves (and presumably also those of other foreign-owned banks) held at the Central Bank have been removed and placed in a trust to support local banks. The decree converting certain dollar loans at par but leaving dollar liabilities in dollars has forced an oversold position of $800 million on HSBC, a completely unacceptable risk tantamount to expropriation. Suspension of the law prohibiting the Government from seizing bank deposits is also deeply concerning.

HSBC’s longstanding policy of standing behind its branches and subsidiaries around the world is predicated on our ability to manage our liquidity and the major risks within a foreseeable political and economic framework; we believe this is no longer the case in Argentina.

We will do everything we can to mitigate our position, but based on our experience so far, we can envisage circumstances which would make it very difficult for us to recommend to our Board additional investment in Argentina.100

A letter from Bond to Holdings directors, also on the 9th, concluded bleakly enough: ‘At present, we are being shielded from the worst effects of these and other measures by the Government’s restraints on withdrawal of bank deposits, but when the Government allows the public to withdraw their deposits we will be faced with a very serious liquidity problem. As well as exchange losses, as we endeavour to collect and convert peso loans into dollars to repay depositors. The losses are likely to consume our current equity in a relatively short time, then we will be faced with the decision, either to inject more capital into Argentina or to suspend our operations there.’101

The Argentine government mitigated the liquidity threat with a new banking restriction, introduced on 10 January, which converted a large proportion of savings into fixed-term deposits, making them inaccessible for at least a year.102 Once again, hordes of middle-class protesters took to the streets, but there were also reports of gangs of youths attacking foreign banks.103 ‘The situation here continues to change by the minute, with one more crazy piece of legislation replacing the next one,’ Smith told Bond on the 16th. ‘The position in the country is very tense with a xenophobic frenzy by all parts of the population against the foreign banks. Branches of Citibank, Boston, BBV and Santander were destroyed yesterday in a number of provincial towns. Our staff are under intense pressure from very frustrated and sometimes violent customers. It is only a matter of time before there will be some casualties.’104 The major foreign banks operating in Argentina had meanwhile convened informally in New York on the 14th under the auspices of the Institute of International Finance (IIF), the global association of financial institutions. Flint, representing HSBC, subsequently reported IIF vice-chairman Bill Rhodes, formerly of Citibank and a veteran of many debt reschedulings, as having asserted that ‘the actions of this government were more damaging and dangerous than any he had encountered before’. Flint’s report continued: ‘It is clear all banks see their capital as lost and will not commit further funds to their Argentina operations either by way of capital or liquidity. All agreed that the multilateral agencies were lacking in focus and commitment currently and regretted the muted reaction of G7 central bankers at their recent meeting. Rhodes undertook to get the Fed interested and engage the US Treasury.’105

Hide-bound by the corralito, Argentina’s banking system was operationally largely suspended during 2002. However, no fewer than 180,000 court judgments were obtained by individual claimants, ordering the payment of dollar deposits at the pre-devaluation exchange rate − to the dismay of the banks. Two foreign banks, Canada’s Scotiabank and France’s Crédit Agricole, decided to cut their losses and walked away from their Argentinian subsidiaries.106 Withdrawal was discussed at HSBC, but senior executives recoiled from the step since ‘there are, however, many considerations, not the least of which being HSBC’s duties and obligations to depositors and 4,000 staff’.107 Shareholders’ interests were also of vital concern, and during 2002 it was agreed at board level that the $1.2 billion of provisions was ‘our pain threshold’.108 It remained an extremely difficult period – especially for those on the ground. In October 2002, Smith warned Whitson that ‘the situation has become even more ridiculous. The Senate are now accusing bankers of treason! I’m not sure where this will end.’109

Despite everything, somehow, by the end of the year HSBC was still there and an annual operating plan was expected at head office. ‘HSBC Argentina: Going Forward’, put together in late 2002, was, not surprisingly, a tentative and scarcely coherent document – its significance was that there was a forward vision to be written about at all.110 After the dust had settled and the political situation had calmed, HSBC reckoned the Argentinian financial crisis had cost it some $1 billion. At times the local operation had been mere days away from running out of money, but HSBC hoped that its staying power would reap rewards in the future. The underlying prospects for Argentina still looked promising, but it remained to be seen whether the country, and HSBC, would be able to turn those prospects into something more concrete.

Latin America in the HSBC Group

In the early 1990s, HSBC’s footprint in Latin America was tiny. For a bank with global ambitions it was an area that obviously required attention. By the end of the decade its presence in the region was transformed with significant purchases in the more populous and economically developed countries − with one notable exception, the country which had made much of the early running: Mexico. The government there had put Banca Serfin (in which HSBC already had a 19.9 per cent stake) up for sale in 1999, but HSBC’s bid had not been the highest on the table and it had lost out to Santander.

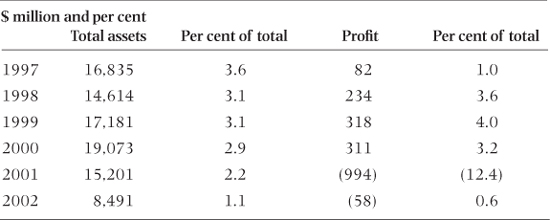

The years immediately after the acquisitions in Argentina and Brazil saw those new members of the Group making healthy contributions to HSBC’s profits, with the region providing 4 per cent of the total in 1999. Although the woes in Argentina dragged these figures down in 2001, recovery was in progress by 2002 (see Table 5).

Table 5 HSBC Latin America total assets and profits, 1997–2002

Source: HSBC Holdings plc, Annual Report and Accounts, 1997–2002

There was no doubt that Latin America provided HSBC’s management with more than its fair share of thrills and spills during these years. The new acquisitions allowed HSBC to remind shareholders and analysts about two of its trademark qualities: turning round troubled acquisitions (using its mobile and adaptable International Officers) and riding out an economic storm (using its strength and experience). The Argentinian drama also provided a refresher course in crisis management to the team at head office. ‘The lesson learnt there’, as Mike Smith would put it later, ‘was that in a crisis it’s always just about liquidity, liquidity, liquidity.’ 111

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 15