Native American tribes of Pennsylvania. Lauren Winkler.

PENNSYLVANIA’S BORDERS

How They Got that Way

By Gregory F. Scott, PE, and Jodi S. Klebick

FIRST PEOPLES

The establishment of what is we now recognize as the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania began in 1681, although this land was inhabited long before that date by Native Americans. As evidenced by artifacts from the Meadowcroft Rockshelter in Washington County, Pennsylvania, the area may have been continually inhabited for more than nineteen thousand years, since Paleo-Indian times. At the time of William Penn’s arrival, there were about twenty thousand Native Americans living in what is now Pennsylvania. These people collectively belonged to two groups made up of many tribes, based on the languages they spoke: the Algonquin and the Haudenosaunee—more commonly called the Iroquois Confederacy of tribes. The Lenape and the Munsee tribes were offshoots of the Leni-Lenape (meaning “True People”) tribe of the Algonquins who inhabited the eastern portions of current-day Pennsylvania along the Delaware River and were therefore commonly known by settlers as the Delaware Indians. The Susquehannock tribe lived along the Susquehanna River to which they gave its name. Northern portions of modern Pennsylvania overlapped the southern boundaries of the Iroquois Confederacy, with the Oneida and Seneca tribes being the largest groups in this region. The far northwest was once occupied by the Erie tribe. The balance of what is now central and Western Pennsylvania was inhabited by the Shawnee peoples, who were also in the Algonquian language group. The boundaries of the land controlled by Native American peoples were never formally established by survey for “landownership” as understood by colonizing western Europeans.

Native American tribes of Pennsylvania. Lauren Winkler.

Throughout the course of their history, Native American cultures rose and fell due to variations of food availability, tribal warfare and cultural assimilation. The Monongahela culture was one such people whose presence gave its name to a significant river in Western Pennsylvania, but that culture had vanished by the beginning of the 1600s. Also affecting Native American peoples and the extent of their occupation of this region was the introduction and spread of European diseases. Long before Europeans penetrated into what is now Pennsylvania, infectious diseases were being transmitted via indigenous peoples themselves via trade routes from the coastal plains inland.

While these tribes are almost wholly extinguished from what is now Pennsylvania, their presence is still felt in the names of many rivers and places in the region. Names such as Youghiogheny, Allegheny, Aliquippa and Punxsutawney are their lasting reminders. It is important to remember that these original “Pennsylvanians” were the first to navigate the state’s streams and rivers, build settlements that later turned into towns and cities and blaze the pathways that were the first overland transportation links, many of which were later established as the state’s first roads.

PENN’S WOODS

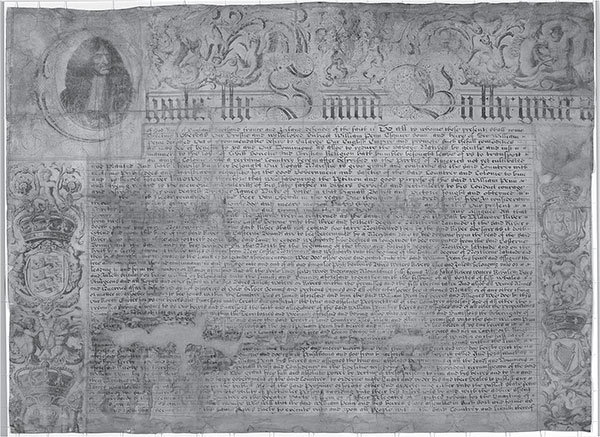

Pennsylvania, meaning “Penn’s Woods,” formally came into being in 1681, when King Charles II of England used a grant of land to settle debts with William Penn that he had inherited from his father, Admiral Sir William Penn. By the late 1600s, the only available tract of land controlled by the English in eastern North America was south of New York, west of New Jersey and north of Maryland. On March 4, 1681, His Majesty King Charles II signed the Pennsylvania Charter, which states:

Doe give and grant unto the said William Penn, his heires and assignes all that tract or parte of land in America, with all the Islands therein conteyned, as the same is bounded on the East by Delaware River, from twelve miles distance, Northwarde of New Castle Towne unto the three and fortieth degree of Northern latitude if the said River doeth extend soe farre Northwards; but if the said River shall not extend soe farre Northward, then by the said River soe farr as it doth extend, and from the head of the said River the Easterne bounds are to bee determined by a meridian line, to bee drawn from the head of the said River vnto the said three and fortieth degree, the said lands to extend Westwards, five degrees in longitude, to bee computed from the said Easterne Bounds, and the said lands to bee bounded on the North, by the beginning of the three and fortieth degree of Northern latitude, and on the south, by a circle drawne at twelve miles, distance from New Castle Northwards, and Westwards vnto the beginning of the fortieth degree of Northerne Latitude; and then by a straight line Westwards, to the limit of Longitude above menconed.

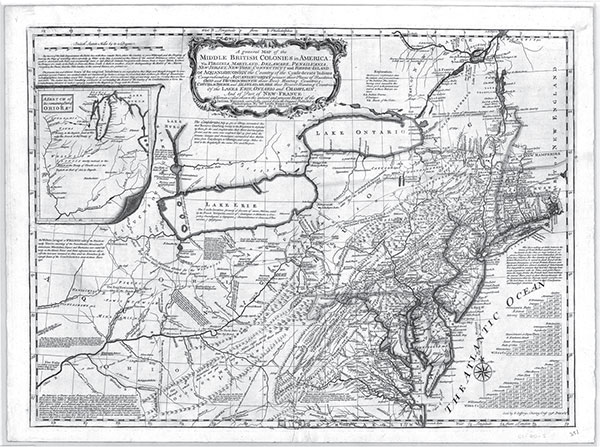

Map of middle British colonies in America. MG-11.1, map no. 874, Record Group 10, Office of Governor Robert P. Casey, proclamations (series#10.3). Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Pennsylvania State Archives.

The eastern boundary of the Delaware River was clearly established, as it sat on a geographical feature. But the western boundary, according to the charter, was to be five degrees in longitude west of the eastern boundary, thereby giving the colony somewhat parallel boundaries on its east and west extents. More troublesome were the northern and southern boundaries.

The Pennsylvania Charter determined the northern border to be the forty-third degree of latitude (just above present-day Buffalo, New York), well within the borders of the Dutch Province of New Netherland, which was ceded to England in 1667. The southern boundary was even more difficult to establish, as the point of beginning for its southeastern boundary did not even exist. The charter started with the intersection of a circle twelve miles from New Castle (now located in Delaware) and the beginning of the fortieth degree of latitude; however, the fortieth degree is so far north of New Castle that the lines never intersect. The fundamental problem was a poor understanding at that time of where the fortieth degree of latitude actually lay. Dating back to the first maps from the settlement of the Virginia Colony, the head of the Chesapeake Bay was thought to be just below the fortieth degree, but the fortieth degree actually falls well north of Philadelphia. The Maryland Colony was carved out of the Virginia Colony for Lord Calvert but had an undefined western limit (which wasn’t set until 1897, and its southern border with West Virginia wasn’t settled until 1912 by the U.S. Supreme Court, but that’s another story). Beyond that, Virginia had a claim to the fortieth degree of latitude as well, and the vagaries of the royal charters even gave rise to claims on the land north and west to the Mississippi River.

First page of the 1681 Pennsylvania Charter. RG-26.2, 1681 PA Charter, page 1, Record Group 10, Office of Governor Robert P. Casey, proclamations (series#10.3). Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Pennsylvania State Archives.

These claims were mostly moot at the time because they gave no consideration to the claims by the French Crown to land beyond the Appalachian Mountains or to the Native Americans who inhabited these lands. A desire to compensate the Native Americans for their land, along with Quaker pacifism espoused by the Penn family, enabled Pennsylvania to settle the southeast region of what is now Pennsylvania during the “long peace” under Indian-brokered alliances.

Borders with neighboring colonies had not yet become important enough to be determined when continual western expansion of settlers in the first half of the 1700s, aided by the Iroquois Confederation “permission,” resulted in expropriation of lands under control of the Lenape and Shawnee peoples. These conflicting land claims played a large part in sparking the Seven Years’ War, which lasted from 1756 to 1763. The 1763 Treaty of Paris, which ended the war, removed the French claims on North America and for the first time made relevant the question regarding what the western borders of the colonies were. On October 7, 1763, King George III of England issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763 forbidding colonial settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains, effectively determining these boundaries by royal decree and thus voiding grants of lands farther west made earlier.

Adjustments were made to the 1763 line in the 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix and the Treaty of Hard Labor, as well as again in 1770 in the Treaty of Lochaber. However, resentment of England by the colonies, especially the restrictions on new land, continued to grow, resulting in the American Revolution. Upon signing the Treaty of Paris ending the Revolutionary War in 1783, the United States would become the final arbiter of the official borders of Pennsylvania.

Royal proclamation of 1763. Lauren Winkler.

SURVEYORS TOOLS

One of the earliest written descriptions of a surveyor is contained in Master John Fitzherbert’s The Art of Husbandry, published in 1523. In it, the surveyor’s feudal role was that of executive officer for a landed nobleman. The French words of sur (over) and voir (see) described the surveyor’s duty to oversee the nobleman’s estate. When the English landed gentry began enclosing land during the reign of the Tudors, the visual inspection of the estate and the written report describing the “buttes and bounds” and the rent or service due from the land’s tenants grew in importance. The need to measure and map the holdings fell on the surveyor to determine where the estate’s boundaries abut (or, to use another French word, mete) other boundaries, hence the work of the surveyor was to produce the “metes and bounds” of a property.

Early surveying equipment. RG-17.394, Box 4, image no. 5078, Record Group 10, Office of Governor Robert P. Casey, proclamations (series#10.3). Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Pennsylvania State Archives.

Standardized topographical surveying was made possible by the inventions of a seventeenth-century English mathematician Edmund Gunter. In 1624, Gunther published The Description and Use of the Sector, the Cross-Staffe, and Other Instruments for Such Studious of Mathematical Practise. In his book, Gunter described a chain four perches in length made up of one hundred links. A perch was sixteen and a half feet, and Gunter’s chain therefore measured sixty-six feet in length. His one hundred links allowed the easy conversion of a measurement system based on four to the new decimal system based on ten. The introduction of the precision Theodolite in the early 1700s combined with trigonometry would be the tools used by surveyors until the advent of electronic distance measurement in the 1950s, total stations in the 1970s and the widespread adoption of Real Time Kinematic surveying using Global Positioning Systems in the 1980s.

SETTLING PENNSYLVANIA’S BORDERS

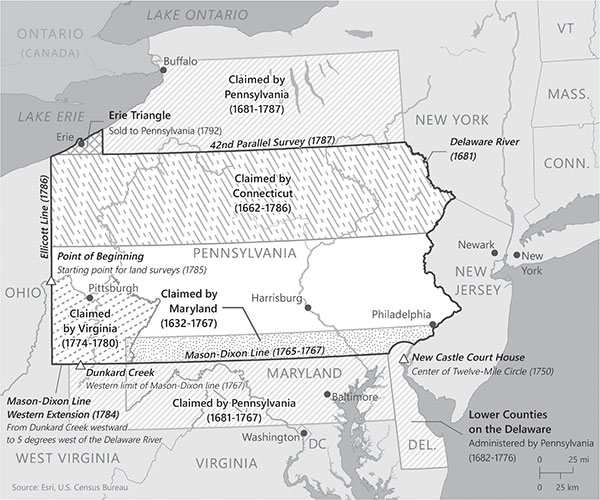

Geographic inaccuracies contained in Pennsylvania’s 1681 charter and the other colonies’ vague borders created great confusion between the Penns of Pennsylvania, the Calverts of Maryland and even the landed gentry of New York and Virginia. Disputes over property rights and jurisdictional enforcement caused by these competing land claims even resulted in violence. Cresap’s War broke out in 1730 over conflicting land claims from Thomas Cresap, a Marylander, and Quaker minister John Wright, a Pennsylvanian in the region that is now York County, Pennsylvania. The colony of Maryland deployed its militia in 1736, and Pennsylvania responded in kind in 1737. Only intervention by King George III of England in 1738 prompted a cease-fire and established a compromise boundary between the two conflicting claims. The border between Pennsylvania and Maryland was agreed to as the line of latitude fifteen miles south of the then southernmost house in Philadelphia.

In 1763, the Penns and Calverts commissioned two highly skilled Englishmen, astronomer Charles Mason and surveyor Jeremiah Dixon, to accurately establish the Pennsylvania-Maryland border, as well as the Delaware Colony’s borders with both Pennsylvania and Maryland. In April 1765, Mason and Dixon began work on the Pennsylvania–Maryland survey, which was fixed as the 39° 43’ N parallel. The boundary was marked by stones every mile (milestones) and crownstones every five miles. The four-sided stone obelisks were shipped from England expressly for these purposes. Milestones had the letter M carved on the side facing Maryland and the letter P carved on the side facing Pennsylvania. Crownstones also included the coat of arms for the Calverts and Penns. Many of these stones are still visible today. Mason and Dixon extended the boundary survey 232 miles west until October 8, 1767, to near present-day Mount Morris, Pennsylvania.

Having crossed a war path just east of Dunkard Creek, they were informed by their Iroquois guides that they could not continue. Mason recorded in his journal, “This day the chief of the Indians which joined us in the 16th day of July informed us that the above-mentioned war path was the extent of his commission from the chiefs of the six nations that he should go with us, with the line: and that he would not proceed one step farther westward.” The termination of the survey in 1767 was 21.65 miles short of Pennsylvania’s western boundary. The methodology developed by Mason and Dixon for the survey utilized the most precise portable astronomical telescope of the time, an astronomical clock, tables of star positions, a Hadley’s quadrant, a transit, spirit levels, surveyor’s chains and wooden rods. Its accuracy was within inches of the best techniques available into the twentieth century before the advent of Global Positioning Satellites (GPS). The technique used by Mason and Dixon, known as the “secant method,” was the basis for subsequent large-scale precise boundary surveys in the United States.

After the Treaty of Paris in 1783 ended the Revolutionary War, the now independent states attempted to reassert their boundary claims from their original charters—even Connecticut, citing its 1662 charter that granted it rights to all lands to the west of the colony to the Pacific Ocean, unless they were owned by another “Christian prince or state.” Taking this to exempt New York, which was a Dutch colony at the time, Connecticut claimed the northern third of what is now Pennsylvania. Connecticut even organized settlement efforts resulting in the Yankee-Pennamite Wars with Pennsylvania settlers. The war, which flared up in the Wyoming Valley between 1769 and 1775, only ceased with the beginning of the Revolutionary War.

Pennsylvania Mason-Dixon line historical marker. RG-12.14, image no. 249, Record Group 10, Office of Governor Robert P. Casey, proclamations (series#10.3). Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Pennsylvania State Archives.

It was Virginian Thomas Jefferson who recognized that the new American government required funds and that the sale of public lands could provide them. Virginia’s own claims to the Forks of the Ohio could be argued by its charter and made legitimate by its original construction of Fort Prince George in 1754 (the Virginians were subsequently chased out by the French, who demolished the English fort and erected Fort Duquesne in its place) and the seizure by force from the Native Americans of what became Pittsburgh in Lord Dunmore’s War in 1774. Facing a national debt estimated to be over $40 million at the time (about $1 billion in 2018) and having no means to impose tariffs or taxes over the objection of the states, on March 1, 1784, Congress approved Jefferson’s proposal that Virginia cede all claims to the land west of Pennsylvania as originally established in its charter (five degrees in longitude from its eastern border), and the other states did likewise. There remained joint commissions in 1786 and 1782 to settle the issue of the rights of settlers from other states within Pennsylvania—this being a time when the concept of being an American was secondary to one’s state allegiance. However, there remained the question of where exactly the western border of Pennsylvania fell.

In 1784, surveyors Andrew Ellicott, from Maryland, and David Rittenhouse, from Pennsylvania, were tasked with completing the survey of the Mason-Dixon line that had been abandoned seventeen years earlier. Upon completion of this task, Ellicott and Rittenhouse were appointed in 1786 to lead a boundary commission to conduct a survey to define the western border of Pennsylvania and the Ohio Country. The survey team that headed out to the then-rugged frontier was headed up by Thomas Hutchins, and the border they determined was called the Ellicott Line. Evidence of their work can be seen today where Pennsylvania Route 68 becomes Ohio Route 38 just east of East Liverpool, Ohio, as it traces the northern shore of the Ohio River and crosses from Pennsylvania to Ohio. Standing alongside the highway sits a barely noticed but significant stone obelisk. The “Point of Beginning” marks the western boundary of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. The monument carries an inscription that reads, “The Point of Beginning. 1112 feet south of this spot was the point of beginning for surveying the public lands of the United States. There on September 30, 1785, Thomas Hutchins, first Geographer of the United States, began the Geographer’s Line of the Seven Ranges.”

The importance of the Ellicott Line (running south–north at longitude 80° 31’ 12”) was that it was to become the first principal meridian used in the Public Land Survey System, created by the Land Ordinance of 1785 to survey the Seven Ranges in eastern Ohio under the oversight of the Surveyor General’s Office. This survey system was then used to survey the majority of the United States. The surveyor general eventually became part of the General Land Office, which later became part of the U.S. Bureau of Land Management. Until this day, the U.S. Bureau of Land Management still manages the State Plane Coordinate System.

Pennsylvania borders and historical land claims. Lauren Winkler.

The conflicting claims for Pennsylvania’s northern border began to be settled in 1785. A compromise was reached between Pennsylvania and New York that their shared border would be set at the forty-second parallel, versus the forty-third parallel as described in Pennsylvania’s original charter. The survey was completed in 1786 by Andrew Ellicott, representing Pennsylvania based on the state’s satisfaction with his earlier surveys, and with Revolutionary War general James Clinton and Surveyor General of New York Simeon DeWitt representing New York. The western edge of New York was established twenty miles east of the peninsula jutting into Lake Erie, called Presque Isle (“almost an island” in French). This survey was approved by Pennsylvania and New York in 1787, but it left a remaining three-hundred-square-mile triangle of land claimed by Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut and Massachusetts. This area became known as the “Erie Triangle.” As Pennsylvania was landlocked, the new federal government pressured all four states to surrender their claims and subsequently sold the land to Pennsylvania on March 3, 1792, for $0.75 per acre, for a total value of $151,640.25.