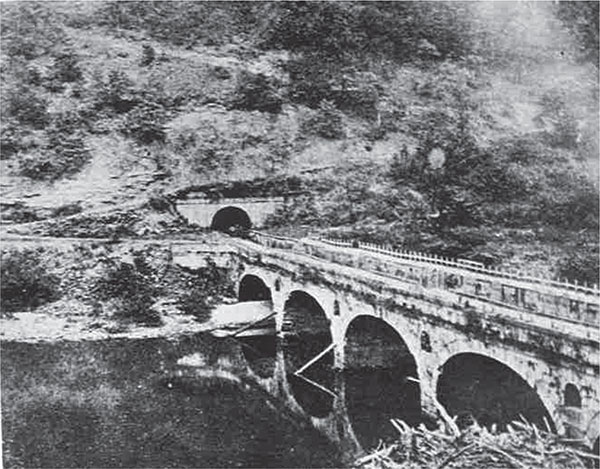

A stone arch bridge carried the canal across the Conemaugh River and into a tunnel that is now plugged for the Conemaugh Reservoir. A corrugated metal pipe, which drains the tunnel below the plug, now marks its location. Ms. Nancy O’Dell.

CANALS

By David L. Wright, PE

EARLY TRANSPORTATION: SLOW, EXPENSIVE AND HAZARDOUS

As early as 1768, a few daring pioneer families with their household goods passed Pittsburgh on their way westward down the Ohio River to new settlements. By building covers, rafts became houseboats to be floated downriver and then broken up for materials at the end of the trip. Keelboats were built with design similar to the eastern Durham boat. The boats were rowed, poled from the sides or pulled from the bank upstream after a relatively easy trip downstream. Trips began in the late fall and early spring, when the water was high enough. In addition to low water in the summer, river hazards included rapid waterfalls (called riffles), gravel bars, floating trees and snags hidden under the water.

Robert Fulton and Nicholas Roosevelt built the New Orleans, the first steamboat on the western rivers, featured at Pittsburgh in 1811. Captain Henry Shreve of Brownsville developed a shallow-draft, light engine boat that served as the prototype for all riverboats to be built in the next hundred years. He also broke the Fulton monopoly on the western rivers. Shreve used double-hull boats to remove river snags. By 1835, 304 steamboats had been built in Pittsburgh, 221 in Cincinnati, 103 in Louisville and the remaining 56 in other towns along the rivers. Pittsburgh also became the center of manufacturing steam engines that were installed in boats up and down the rivers.

Pioneers could use Forbes’ Road and Kittanning Path over the mountains from the east. Movement on roads was slow and expensive. One writer in 1812 stated, “It requires a good team of five or six horses from 18 to 35 days to transport 2500 to 3500 pounds of goods from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh.”

ENGINEERING THE SOLUTION

Canal transportation made Britain’s English Midlands the center of the Industrial Revolution between the 1760s and 1800. Raw materials imported from the colonies could be transported to the factories of Manchester and Birmingham and then carried out as finished products to the port cities to be shipped all over the world. The British also built primitive railroads to carry minerals from mines. Timber rails were fastened to wood or stone sleepers, with metal bars spiked in on top to reduce wear. Trains were powered by animals and locomotives pulling on level track, utilizing the force of gravity to coast down hills and steam-driven stationary engines to pull up hills.

The American canal “boom” started in New England in 1802, using British technology, with the opening of the Middlesex Canal. In 1810, New York State laid out plans for a canal from the Hudson River, near Albany, across the state to Lake Erie. The Mohawk River had sliced a gorge through the Allegheny Ridge at Little Falls, making an all-water route feasible, and the Hudson River, tidal all the way to Albany, provided easy steamboat navigation to New York City.

The Erie Canal was an instant success. Time to travel from Albany to Buffalo was reduced from thirty-two days to five days. Canalboats, pulled by a team of mules or horses, could carry about seventy tons of cargo compared to a wagon, which could maybe carry about two tons. A year after it opened in 1826, about seven thousand boats were operating on the canal. The canal commissioners collected tolls of $500,000, five times the interest due on the canal’s outstanding bonds. In 1837, the commissioners reported that the entire debt had been repaid. In the eleven years after the Erie Canal opened, the value of New York City real estate tripled, and its population had quadrupled by 1850.

THE PUSH FOR CANAL DEVELOPMENT IN PENNSYLVANIA

As early as 1762, in order to develop trade, Philadelphia merchants requested that a board be appointed to explore the possibility of connecting the West Branch of the Susquehanna River with a tributary of the Ohio River. Philadelphians finally initiated canal legislation after the Erie Canal became a reality. They sent leading Greek Revival architect William Strickland and his assistant, Samuel Honeyman Kneass, to England to study canals and make drawings.

The legislature appointed a three-man commission to survey a route to connect the Susquehanna and the Allegheny Rivers. On February 2, 1825, it proposed a continuous waterway by constructing a four-and-a-half-mile-long tunnel under Allegheny Mountain between what is now Lilly and a point in Blair’s Gap above what is now Hollidaysburg. This seemed possible because the British had already constructed more than forty miles of canal tunnels at that time, the longest being the three-mile-long Standege Tunnel, which opened in 1811 on the Huddersfield Narrow Canal in northern England. However, in his minority report, Charles Trcziyulny doubted the practicality of such a long tunnel. Not only was it too costly and time-consuming to construct, but the mountain also did not provide an adequate water supply to operate the numerous canal locks required to reach the tunnel.

Because many of Philadelphia’s financial institutions had gone bankrupt as a result of the completion of the Erie Canal, commonwealth legislators quickly approved an act on February 26, 1826, authorizing an uninterrupted waterway between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. Not only was the canal building program undertaken without a plan, but the program also advanced with borrowed money on the assumption that tolls would be collected to pay off the debt. The Erie Canal had been partially financed by a tax on the land along the route, which was predicted to increase in value as trade developed.

CONSTRUCTING THE WESTERN DIVISION CANALBETWEEN PITTSBURGH AND JOHNSTOWN

Nathan S. Roberts, an experienced engineer who served as first assistant engineer of the Rome–Rochester stretch of the Erie Canal, was appointed engineer for the Western Division on April 5, 1826. He promptly started a survey line from the foot of Liberty Avenue in Pittsburgh up the south side of the Allegheny River to the Kiskiminetas River. However, when he reached the steep, unstable slopes coming directly down to the river’s edge upstream of where the Highland Park Bridge is located, where no room was available to construct a canal, he started a second survey line up the north side.

When Roberts submitted his report favoring the village of Allegheny (today the North Side of Pittsburgh) along the north side of the river to the canal board, “two gentlemen appeared as representatives of the citizens of Pittsburgh.” They insisted that under the terms of the law, the canal must start in Pittsburgh. The commissioners authorized construction to start outside Allegheny, from Pine Creek, northward to the Kiskiminetas in the fall of 1826, to provide time to settle the disagreement.

In 1827, the commonwealth legislature authorized construction of 44 miles of canal from the Allegheny River along the Kiskiminetas River and the Conemaugh River to Blairsville. Further extension another 30 miles up to Johnstown at the bottom of Allegheny Mountain was approved the next year. The entire 103½-mile Western Division between Pittsburgh and Johnstown included sixty locks plus the four on the Allegheny Branch and the four between the Pittsburgh Basin and the Monongahela River. It also had sixteen aqueducts across rivers and streams, sixty-four culverts, thirty-nine waste weirs, 152 bridges and two tunnels.

An aqueduct carried the canal across the Conemaugh River into the one-thousand-foot Bow Ridge Tunnel cut through a sharp bend in the river below Blairsville. It was the third canal tunnel built in the United States; the first was at Auburn on the Schuylkill Canal and the second near Lebanon on the Union Canal. This tunnel was plugged to construct the Conemaugh Reservoir to control floods after the 1936 flood. A corrugated metal pipe that drains the tunnel downstream of the plug marks its location.

The route also included ten river dams to create twenty-seven miles of slackwater canal. The first dam, at Leechburg, was 27 feet high and 574 feet long. It backed up the river water to Apollo and supplied water to the canal down to Pittsburgh. Additional dams upriver created slackwater navigation for sections of river valleys too narrow to provide room for a canal out of the river. The canal ran in slack water in Packsaddle Gap through Chestnut Ridge between Torrance and Bolivar, as well as in the Conemaugh Gorge through Laurel Ridge between Seward and Johnstown.

The village of Allegheny became a borough during canal development on April 14, 1828. Streets and lots for Sharpsburg and Tarentum were laid out along the canal when it opened.

A stone arch bridge carried the canal across the Conemaugh River and into a tunnel that is now plugged for the Conemaugh Reservoir. A corrugated metal pipe, which drains the tunnel below the plug, now marks its location. Ms. Nancy O’Dell.

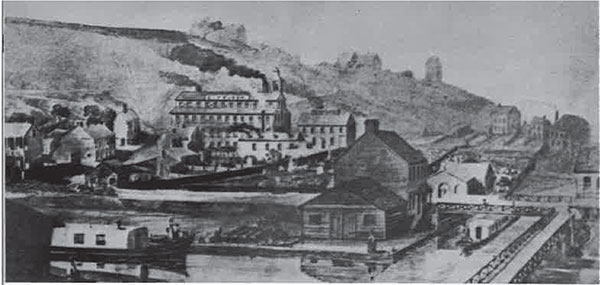

CONNECTING PITTSBURGH TO THE CANAL

Meanwhile, during the winter of 1826, the people of Allegheny and Pittsburgh whipped themselves into a frenzy about the problem of these five miles below Pine Creek. The citizens of Allegheny offered to construct a large canal basin with warehouses and wharves from which freight could be taken by wagon to Pittsburgh across the St. Clair Bridge, now the Sixth Street Bridge, over the Allegheny River. But Pittsburghers had agitated for ten years for a canal and did not want to lose it to the rival town across the river. After sending a committee to the state capital to lobby, the canal commissioners adopted a plan to bring the canal into the village of Allegheny and turn left at a basin to outlet into the river at a location about seven hundred feet downstream of the Sixth Street Bridge. To avoid the toll for wagons crossing the Allegheny River Bridge, the canal commission awarded a contract for a canal aqueduct over the Allegheny River to William LeBaron and Sylvanus Lothrop on June 3, 1827. With seven spans each 160 feet long, the aqueduct was constructed across the Allegheny River along what is now the upstream side of the Norfolk Southern bridge into Eleventh Street. The aqueduct had a wooden trough with heavy, two-and-a-half-inch-thick white pine planks that were laid diagonally in two courses to hold the water. A sidewalk was located along one edge of the aqueduct, and a towpath was located along the other. A roof protected the trusses from the weather.

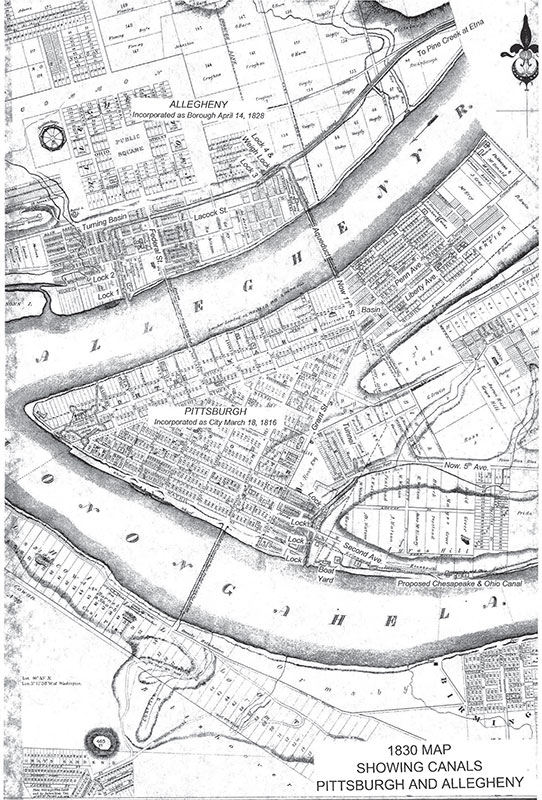

The canal continued on Eleventh Street with a basin on its east side between Penn and Liberty Avenues. An 1852 map also shows a smaller basin built on the west side. The canal ran along the east side of Grant Street. It then curved to the left under what is now the U.S. Steel Building to enter a tunnel under Grant’s Hill. The hill was named for British major general James Grant, who was defeated by the French at that location during the French and Indian War.

Pittsburgh City Council guaranteed to pay the extra cost of the tunnel route to avoid a cheaper route using Smithfield Street or Liberty Avenue, which would have interfered with the free growth of the city. The tunnel was built by cut and cover. This was confirmed when engineers for the Allegheny County Port Authority drilled exploratory core holes in the 1980s for design of the Light Rail Transit line to the south of Pittsburgh.

A cross-section drawing of the Allegheny River Aqueduct shows the wood trough, towpath and roof to protect the trusses from the weather. Ms. Nancy O’Dell.

This 1830 map of Pittsburgh and Allegheny shows the canal locks, canal basin, aqueduct across the Allegheny River and tunnel under Grant’s Hill. Note the proposed Chesapeake and Ohio Canal shown along the Monongahela River. The Gateway Engineers.

Lift Lock No. 4 and the Pittsburgh Weigh Lock were excavated and recorded by GAI Consultants for the I-279 construction project on Pittsburgh’s North Side. Library of Congress HAER Collection.

The canal exited from the tunnel at Forbes Avenue, where water flow was lowered by locks through Suke’s Run into the Monongahela River, and the projected extension of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal. The C&O Canal ended at Cumberland, Maryland, so the tunnel was not used and was allowed to collect silt. It did serve as an overflow channel to carry excess water away from the Pittsburgh basin.

When the canal could first hold water, the passenger boat General Lacock made the first trip into Pittsburgh in 1829. However, parts of the Western Division had their problems. A landslide in Sharpsburg filled up the canal as it was being completed, so it had to be cleared out. The aqueduct across the Allegheny River at the Kiskiminetas River had to be rebuilt twice after floods in 1831 and 1832 badly damaged both the high dam and its lock at Leechburg. Another problem was falling rock fragments from the tunnel at the loop of the Conemaugh River. The problem was repaired between 1830 and 1831 by installing a brick liner for most of its length. It was not until 1834, when the through route from the east opened, that passenger packets and freight boats could maintain a regular schedule.

OVER THE MOUNTAIN ON THE ALLEGHENY PORTAGE RAILROAD

The Board of Canal Commissioners had been appointed in 1824 and prepared several surveys for various routes between Harrisburg and Pittsburgh. On March 21, 1831, the commonwealth passed a law authorizing the Board of Canal Commissioners to commence the construction of the Portage Railroad over the Allegheny Mountain. The board appointed Sylvester Welch, the principal engineer of the recently completed Western Division of the Pennsylvania Canal, to the same position in the building of the Portage Railroad. He nominated, and the Board of Canal Commissioners appointed, twenty-year-old Solomon W. Roberts as his assistant. Roberts had been trained by Josiah White, who was his uncle and manager of the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company. Young Roberts had been a rod man and leveler on fifteen miles of the Lehigh Canal. Moncure Robinson, retained as a consultant engineer for the Portage Railroad, had participated in its previous surveys.

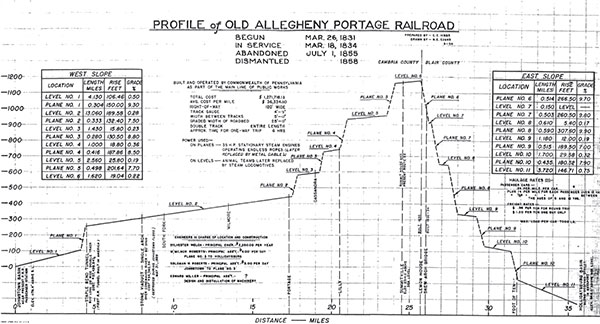

The thirty-six-mile-long Portage Railway was designed with five inclined planes and six levels on both sides of Allegheny Mountain and numbered eastward from Johnstown to Hollidaysburg. The inclines were needed because railroad locomotives, when work began, could not transport passengers and goods along the steep grades over the Allegheny Mountain. Only eighteen months before, the little engine, called “the rocket,” was first demonstrated for the Liverpool and Manchester Railroad. The combination of the tubular boiler with the blast-pipe to force air through the fire was the cause of its success.

The whole total length of the inclines was 4.4 miles, with an aggregate elevation differential of 2,007 feet. Their angles of inclination ranged from 4.15 degrees to 5.85 degrees. The railroad levels between planes were located with moderate grades, and the sharpest curve had a 442-foot radius. The track gauge was 4 feet, 9 inches. Leveling instruments used for the canal were similar to those for the canal, but instruments to lay out curves were poor because a surveyor’s compass was mostly used.

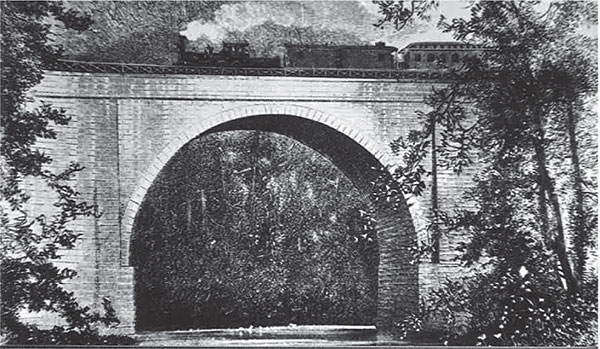

When the surveyors locating the railroad reached the horseshoe bend of the Conemaugh River, about eight miles from Johnstown, Solomon W. Roberts was in charge. A decision was made to cross the stream on a high bridge to avoid two miles of track. The Conemaugh Viaduct, with its seventy-foot-high, single eighty-foot arch span, was later used by the New Portage Railroad and the Pennsylvania Railroad until it was destroyed by the Johnstown Flood in 1889. Bridge construction was directed by Scottish stonemason John Durno. The sandstone used for construction was split from the erratic blocks, often of great size, found lying in the nearby woods. The facing stones were laid in mortar made from silicious limestone found near the spot, without the addition of any sand, and backed by the silicious limestone.

At the Staple Bend of the Conemaugh River, four miles east of Johnstown, a 901-foot-long tunnel was cut through a spur of the Allegheny Mountain to avoid a bend that would have necessitated two and a half additional miles of track. Recognized as the first railroad tunnel constructed in the United States, it was cut through rock to form a 20-foot-high and 19-footwide opening. The eastern, sixteen-mile-long section of the Portage Railroad from the summit down to Hollidaysburg was located by W. Milnor Roberts, who joined the engineer corps in as principal assistant. He and Solomon Roberts had worked together on the Lehigh Canal in 1827. The commissioners awarded contracts in Ebensburg for railroad construction between Johnstown and the summit on May 25, 1831, and from the summit to Hollidaysburg on July 29, 1831. A 120-foot width was cleared the full length of the railroad through the forest of heavy spruce and hemlock timber, many of the trees being more than 100 feet tall. A workforce of about two thousand men was employed at one time for the grading and installation of the 159 stone bridges and culverts.

Conemaugh Viaduct carried the Old Portage Railroad, New Portage Railroad and Pennsylvania Railroad until the Johnstown Flood destroyed it in 1889. Ms. Nancy O’Dell.

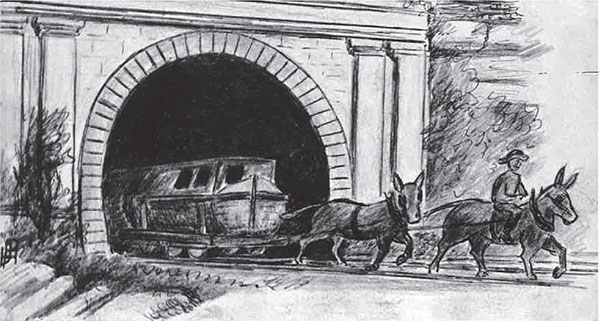

Phill Hoffman’s painting depicts horses/mules pulling a section boat out of the Staple Bend Tunnel west of Mineral Point. Ms. Nancy O’Dell.

In 1831, Edward Miller returned from England, where he studied the most recent railroad technology. As principal assistant engineer, he specified two thirty-five-horsepower steam engines at the head of each plane. Hemp ropes were first used and gave much trouble, as they wore out and broke after a few years of service and varied greatly in length with changes in the weather, although sliding carriages were prepared to keep them stretched without too much strain. John Roebling, a recent German immigrant who had served as a surveyor on the Portage Railroad, saw the problem and developed wire rope that replaced the hemp rope, which was a great improvement.

The laying of the first track and turnouts, with a double track on the inclines, was contracted for on April 11, 1832. The rails weighed about forty pounds per yard and were rolled in Great Britain. Hauling them from the canal at Huntington by wagon was laborious work. Thirteen-pound cast-iron chairs spaced at three feet supported the rails. In most cases, the chairs were bolted to three-and-a-half-cubic-foot blocks of sandstone imbedded in broken stone. These stone blocks were required to be two feet long, twenty-one inches wide and twelve inches deep. A timber foundation with crossties and mud sills, which stood much better than the stone blocks, was used on high embankments. On the inclined planes, flat bar rails were laid on timber rails fastened to the wood crossties.

It was thought that stone sleepers would be better than wood because they do not deteriorate in the weather. However, the attempt to construct track with nonperishable materials failed because the rails spread apart. Many wood crossties were added between the stone sleepers to prevent this. While the engineers strived to build a great public work to endure for generations, the Portage Railroad was replaced by something better about twenty years later. Powered by animals, the first car passed over the road on November 26, 1833, about two and a half years from the beginning of work. By the time the canal navigation opened for the season on March 20, 1835, the second track had been completed.

The Portage Railroad first operated as a public highway, with teamsters driving as they wished, unable to pass in opposite directions on the single track. Soon after opening, the commonwealth authorized the canal commissioners to purchase locomotives to be operated by state employees on a schedule. The first locomotive, named the “Boston” because it had been made in that city in 1834, was put into operation on the longest level, the thirteen-mile section between Johnstown and Plane No. 1. To avoid the cost and delay of unloading and loading freight between canalboats and railroad cars, at each end of the Portage Railroad the shipping companies ran sectional boats that, like modern shipping containers, could be loaded onto railroad cars for the ride over the mountain. After more powerful locomotives made the inclines obsolete, the state constructed the New Portage Railroad to replace the inclines. The railroad was routed up from Hollidaysburg through the Mule Shoe Curve in Blair’s Gap and climbed up the east side of the mountain through a tunnel at the summit. Other sections of the New Portage Railroad bypassed the five planes heading down to Johnstown.

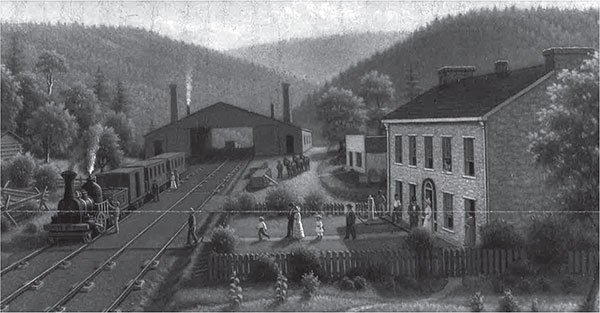

The Allegheny Portage Railroad National Historic Site preserves the Lemon House Tavern and replicas of the Plane 6 Engine House, locomotive and track. Ms. Nancy O’Dell.

The Pennsylvania Railroad Company used part of the New Portage Railroad to build its continuous railroad line across the state between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. Opening the Pennsylvania Railroad across the state in 1852 ended most of the canal traffic. The Pennsylvania Railroad Company bought the Main Line of Pennsylvania canals and railroads across the state in 1857. The Pennsylvania Railroad closed the New Portage Railroad and salvaged its rails to construct its own expansion. The Western Pennsylvania Railroad built its tracks over part of the western division canal after abandonment in 1864.

The National Park Service now offers van tours of the Allegheny Portage railroad from its National Portage Railroad National Historic Site near Cresson. Visitors can view the historic Lemon House Tavern, which served thirsty travelers; a reproduction of the Plane No. 6 Engine House and locomotive; and the skew stone arch bridge, which carried the turnpike road over Plane No. 6. Hikers can walk down the 6 to 10 Trail along the route of the Old and New Portage Railroads from Plane No. 6 to Plane No. 10. Hikers can also use the Portage Railroad from Mineral Point to the Staple Bend Tunnel and Plane No. 1.

BEAVER DIVISION AND ERIE EXTENSION CANAL CONNECTS TO THE WEST

The February 26, 1826 canal act authorized surveying several routes to extend the planned system of canals, river navigations and railroads across the state to Erie and to construct a navigable feeder canal between French Creek and the summit level at Conneaut Lake. In an act passed on January 10, 1827, Ohio incorporated the Pennsylvania and Ohio Canal Company in Ohio to connect a Cross Cut Canal, along the Mahoning River, to a canal planned in Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania followed Ohio with its act to incorporate the Pennsylvania and Ohio Canal Company in Pennsylvania.

In 1828, work started on the French Creek Feeder. The commissioners studied to route a canal from the Allegheny River up French Creek to near Meadville and then on a feeder canal running down along the north side of Conneaut Marsh to the summit level. However, Pittsburgh’s political leaders favored a water route from Pittsburgh to Erie along the Ohio River to Beaver and, from there, up the Beaver and Shenango Rivers to the summit level, connecting with the Cross Cut. Canal near New Castle. As a result, the commonwealth signed the March 31, 1831 act to authorize the Beaver and Shenango Rivers route.

The canal’s principal engineer, Dr. Charles T. Whippo, a former medical doctor who turned engineer for the Erie Canal in New York, submitted his first report, which included a profile map, in July 1831. Because Whippo feared that damming the river would flood the adjacent land, he proposed a canal from a dam to feed from Neshannock Creek, at New Castle, to a point 5.77 miles south at Clarke’s Mills. From there, he proposed slackwater navigation, with a towing path along the east side of the river, southward 14.44 miles as far as Brighton (now New Brighton). He located a canal 1.31 miles through Brighton down to Fallston to avoid damaging the milldams that were in the river. The canal continued as slack water the last 2.72 miles from Fallston to the Ohio River at Rochester.

The canal commissioners accepted his report, and the canal construction work was completed from the Ohio River to Western Reserve Harbor, now called Harbor Bridge, five miles north of New Castle, in 1833. The harbor served as a shipping point for freight and passengers into the Western Reserve area of northeastern Ohio. The last lock on the Ohio River was built extra-large to handle small steamboats. The Cross Cut Canal was completed from its connection at Mahoningtown to Akron, Ohio, in 1838.

W. Milnor Roberts made a thorough inspection and found the canal in poor condition due to flood damage. The cost of repairs far exceeded the income from tolls. After spending $4 million ($126 million in 2017) to extend the canal to Lake Erie, the commonwealth sold the entire Beaver and Erie project to the Erie Canal Company in 1843. Erie business people formed the private company and elected Rufus Reed as president. Reed owned a fleet of sailing ships on the Great Lakes.

The new company spent another $500,000 and completed the canal in 1844. The work included finishing the forty-four-lock, sixty-one-mile Shenango Division to Conneaut Lake, raising the lake level 11 feet to supply water to the summit level and cutting the two-and-a-half-mile summit level 10 to 27 feet deep between the Shenango River and Conneaut Creek. The forty-five-and-a-half-mile Conneaut Division dropped 510 feet from the summit level through composite wood and stone locks to terminate in Erie Harbor at Navy Yard Run below Reed’s Pier. The canal crossed Elk Creek by a gigantic, 400-foot-long and 84-foot-high aqueduct and Walnut Creek by an even bigger 600-foot-long and 100-foot-high aqueduct above the stream. After operating for twenty-six years, the canal was sold in 1870 in a sheriff ’s sale to the Erie and Pittsburgh Railroad Company, a subsidiary of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company. Collapse of the Elk Creek Aqueduct closed the canal one year later.

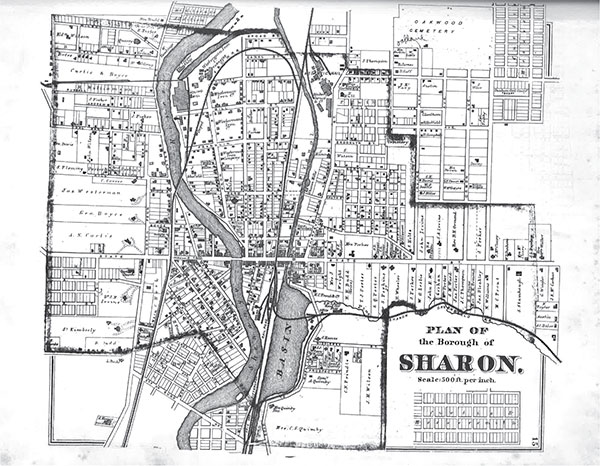

Quaker Steak and Lube Restaurant is located in what used to be Sharon’s canal basin. From the Mercer County 1873 Atlas.

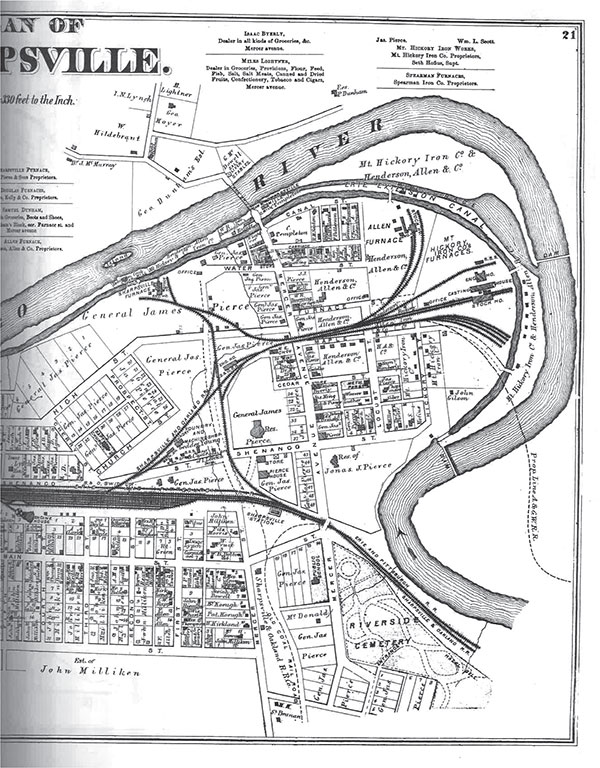

Railroads have moved in and taken the business of these iron furnaces along the canal in Sharpsville. The guard lock at the dam is preserved. From the Mercer County 1873 Atlas.

The only surviving feature of the canal is a guard lock in a public park below the Shenango Reservoir dam on the north side of Sharpsville. The Shenango Trail follows much of the towpath from Big Bend through Hamburg to the Kidd’s Mill covered bridge in Shenango. A segment of watered canal, accessible by the abandoned railroad bed, provides waterfowl habitat in the state game lands south of Pulaski. The wall of upper Girard Lock, in Rochester, supports the Madison Street Pump Station.

In conclusion, doctors, lawyers, architects, surveyors and mechanics turned their abilities to engineering the canals and early railroads needed to develop our country. They designed transportation facilities using technology available at that time from the British Industrial Revolution. As time went on and new technology became available, engineers applied skills and methods first learned during the canal era to design and construct the transportation system we have today.