Braddock’s Road, located at Braddock’s Grave, near Fort Necessity National Battlefield. ASCE Pittsburgh Section.

ROADS AND HIGHWAYS

The Ultimate Independence

By Jason Machuga, PE, and Carrie Machuga

The roads and highways in Western Pennsylvania have changed over time to reflect the needs of the populace and times in which they were developed. They show an evolution from the early adoption of deer paths into native paths, the military importance of early routes to link east to west and the economic importance of connecting the region to commercial centers throughout the United States. These roadways opened up Western Pennsylvania, allowing travel in new ways and to new locations, providing independence that had not been previously possible. Countless and nameless engineers, in particular civil engineers, played important roles in the development of this vital infrastructure.

NATIVE AMERICAN PATHS IN WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA

Native American paths served as the first transportation system in Pennsylvania. They were the first trails blazed through the wilderness that was then the Pennsylvania frontier. Different trails were used for trade, war, hunting and travel; each had a strategic location and design depending on their use. For example, war paths were unique from trade routes in that they were usually located at higher elevations to provide better observation of the enemy. But regardless of their purpose, these paths were the result of rudimentary engineering based on observation and experience. They marked routes with acceptable soil conditions, which were rarely undermined or washed out and were always protected from weather. Several of these paths have served as connections between important parts of Pennsylvania throughout history.

In the early period of settlement in Pennsylvania, travelers from the east would use several paths to reach the Allegheny River Valley. From Carlisle in central Pennsylvania, travelers could use the Frankstown Path (also called the Allegheny or Ohio Path) northwestward to Indiana, Pennsylvania, where it joined the Kittanning Path, which ended at the Allegheny River near Kittanning. A shorter alternate route to the Allegheny Valley would take travelers along the Kiskiminetas Path from just west of Indiana to the Pittsburgh area. This path was the preferred route used by traders during colonial times to traverse the Pennsylvania wilderness.

Prior to the French and Indian War (1756–63), roads were developed only as far west as the Susquehanna River at Carlisle, where the native trails and packhorse trails became the only route over the Alleghenies. George Washington used several of these trails on his first mission to the Allegheny and Ohio Valleys to deliver a message of “cease and desist” to the French and their Native American allies who occupied the area. That message would precipitate the conflict between the British and the French and native allies.

EARLY MILITARY AND PACKHORSE ROADS

General Edward Braddock embarked on an unprecedented campaign from Fort Cumberland in Maryland with the intent to attack the French at Fort Duquesne, where the forks of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers join the Ohio River in present-day Pittsburgh. The 125-mile journey took Braddock and his troops over the steep and rocky terrain of the Allegheny Mountains. Braddock led 2,200 men who included not just soldiers but also “hatchet men,” blacksmiths, miners, teamsters, wheelwrights and military engineers, all of whom were necessary to build a twelve-foot-wide wagon road through the mountains. Just surmounting the first ridge from Fort Cumberland proved a challenge, with the loss of several horses and wagons in those first few days. Braddock’s Road followed Nemacolin’s Path from Cumberland to Chestnut Ridge (just southeast of Uniontown), where it turned northward and toward Fort Duquesne, situated at the forks of the Ohio River, and the Point. In all, the road traversed eight major mountains. Braddock’s troops dragged supplies and heavy artillery along the way just to suffer a horrific defeat in a French and Native American ambush a few miles from Fort Duquesne. Nearly two-thirds of the army was killed or wounded in the battle. General Braddock was fatally wounded and died during the retreat, retracing the road they had fought to build. Braddock was buried in the road, where the ruts from the wagons would make the grave less obvious to any enemy looking for the body.

Braddock’s Road, located at Braddock’s Grave, near Fort Necessity National Battlefield. ASCE Pittsburgh Section.

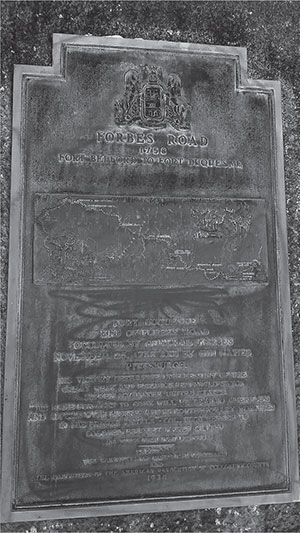

Monument commemorating Forbes’ Road from Fort Bedford to Fort Duquesne in Point State Park, Pittsburgh. ASCE Pittsburgh Section.

General John Forbes led another mission to take the French Fort Duquesne in 1758. He built his road on a wagon trail that had been opened four years earlier between Shippensburg and Bedford. Forbes’s army extended the road over the Raystown Path to just west of Ligonier. The army traveled through the woods from there to Fort Duquesne, in the hopes of surprising the French, only to arrive to find the fort burned and abandoned. In place of Fort Duquesne, the British built Fort Pitt, in honor of the British secretary of state William Pitt, who had been instrumental in turning the tide of the French and Indian War in favor of the British. Over the next five years, Forbes’ Road, the reopened Braddock’s Road and Burd’s Road, a new road from Gist’s plantation (about five miles southwest of Connellsville) to Brownsville, were maintained by the British army to transport supplies to support the final defeat of the French in the Pennsylvania frontier.

WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA’S FIRST BUILT ROADS

During the latter half of the eighteenth century, many roads were developed in the southeastern section of Pennsylvania (near Philadelphia), while the western region lagged far behind in road development. Forbes’, Braddock’s and Burd’s Roads were maintained during the French and Indian War but were left to deteriorate until after the American Revolution.

The first formalized connection between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh was the Pennsylvania Road, completed in the 1790s. Its alignment included portions of some existing paths and roads, such as the Allegheny Path, the Raystown Path, Burd’s Road and Forbes’ Road. The Pennsylvania Road was a state road spearheaded by Hugh Henry Brackenridge, who first lobbied in the state legislature for improvement to the east–west transportation system in the early 1780s. Throughout the remainder of the eighteenth century, several acts and appropriations from the legislature authorized surveys and construction on the road’s westward advance. The final alignment of the road was roughly the same as today’s Lincoln Highway, following the main line of Forbes’ Road over the Allegheny Mountains to Ligonier and diverging a few miles south to Greensburg and then on to Pittsburgh.

The William Penn Highway was surveyed first from Frankstown to the Conemaugh River in Blairsville in 1787. It was initially designed as a connection between the Susquehanna and Ohio River systems, by way of the Frankstown Road. The highway was extended along the Conemaugh River to Loyalhanna Creek and made passable for wagons in 1789. In the early years, the road was used primarily for transporting iron from the Juniata area to Pittsburgh. In 1807, the road was extended all the way into Pittsburgh. It was originally called the Huntington Pike, but over several years, the name evolved to the William Penn Highway.

The National Road, also known as the Cumberland Road, was the first road built entirely with federal funds. The road was initiated in an 1802 act that allowed the residents of Ohio to form a state government and join the United States. The act included a provision that said, “One-twentieth of the net proceeds of the lands lying within said State sold by Congress shall be applied to the laying and making of public roads.” Previously, roads had been entirely the responsibility of the states, and this federal action in the realm of transportation caused considerable controversy that haunted the National Road throughout its history.

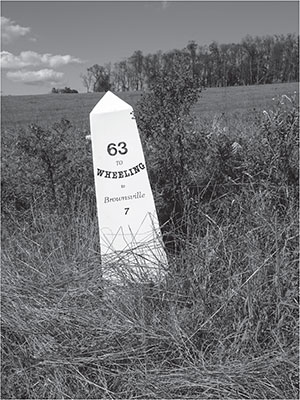

In 1805, President Thomas Jefferson authorized the study of potential routes to Ohio from the Eastern Seaboard. The committee studying possible routes recommended that the road begin in Cumberland, Maryland, and traverse Pennsylvania and present-day West Virginia to the Ohio River in Wheeling. In 1806, Jefferson signed a law “to regulate the laying out and making a road from Cumberland, in the State of Maryland, to the State of Ohio.” The National Road between Cumberland and Wheeling officially opened in 1818 with a hard stone surface. As traffic exceeded expectations, the roadway was soon reconstructed with macadam, an early hard surface used for roadways. The completed alignment traveled over Nemacolin’s Path, over the mountains, along the Youghiogheny River and Braddock’s Road to Brownsville and Washington, Pennsylvania, and finally to Wheeling. Today, much of the National Road alignment is followed by US Route 40.

Replica National Road marker. ASCE Pittsburgh Section.

Searight’s Tollhouse along the National Road, north of Uniontown. ASCE Pittsburgh Section.

The National Road opened the western frontier to those searching for new, rich land to start their lives. Towns along the road began to grow, offering services to those traveling or for those travelers to stop and settle. As such, Cumberland, Uniontown, Brownsville, Washington and Wheeling became industrial centers. Congress originally planned to extend the road all the way to the Mississippi River. Extension required agreements, like the one made with Ohio, to be completed with each state that the road would pass through, and Congressional appropriations were needed for each stage. Maryland, Pennsylvania, Ohio and Virginia (now West Virginia) had accepted their portions of the National Road between 1831 and 1834 and immediately passed legislation to toll the road to maintain it. After $6,759,257 of federal funds had been spent on the road, the federal government turned the entire road back to the states in 1850.

By the 1850s, traffic had begun to decline on the National Road as railroads offered faster, more comfortable travel than the stagecoaches that used the road. In southwestern Pennsylvania, residents fought the expansion of the railroads in the area, knowing that they would begin the end of the National Road. When the Pennsylvania and B&O Railroads reached the area, the prosperity along the road began to decline as many of the businesses that had sprung up to support the National Road closed.

Another unique type of roadway that was found near Pittsburgh was part of the “Plank Road Craze,” which began in Pennsylvania shortly after the first American plank road was built in upstate New York in 1846. Using wood to pave roads rather than stone was significantly cheaper: $1,500 per mile for a plank road compared to the $10,000 per mile cost of the National Road. The Alleghany and Butler Plank Road Company was one of the oldest and most successful of the private companies formed to build and toll these plank roads. Its Butler Plank Road was one of the most profitable plank road operations in the state. The road was twenty-seven miles long and connected Etna and Butler, Pennsylvania.

The Butler Plank Road, initially paved with flagstone, was popular with stagecoaches traveling between Butler and Pittsburgh. As the iron rims of the wagons using the road cut into the soft flagstone, it was replaced with wooden planks in the 1870s. This was considered an “engineering marvel of the times.” According to the Shaler Historical Society, the wooden planks are still under the modern road that has replaced it. The planks were eight feet long and about three inches thick, split directly from logs and hand-hewn on top. It was typical of other plank roads, with the wooden pavement only wide enough for one-way traffic. The planks were occasionally offset at “turn-offs,” where wagons could drop off the planks onto the adjacent dirt surface to allow others to pass. Tolls were collected at four toll gates along the Butler Plank Road.

Not surprisingly, plank roads survived just several decades at the most, due partly to competition from railroads at the time but also to the maintenance they needed. Wood planks had to be replaced on average every decade. There were at the time no wood preservatives that could protect the planks from rotting from the weather and sitting in the damp earth, and planks also often broke under the weight of the heavy wagon loads. Most of the plank road companies failed or closed before the end of the 1800s, unable to manage the repair and maintenance costs with their shrinking toll revenues.

THE FIRST AUTOMOBILE HIGHWAYS

As canals and railroads devalued the importance of earlier good roads, the birth of the automobile quickly reestablished the need for functional highways. One of the earliest and perhaps most important automobile highways was the Lincoln Highway. The Lincoln Highway was the brainchild of Carl Fisher, known previously for development of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. The Lincoln Highway Association was founded in 1913 by Fisher and several other industrialists. Their goal was to create a hard-surfaced route extending from coast to coast that would keep motorists from getting stuck in the mud. Using private donations, the association promoted good roads along the designated route. Connecting New York City’s Times Square with the Pacific Ocean in San Francisco, the Lincoln Highway route went directly through Pittsburgh. In Pennsylvania, the Lincoln Highway followed the path of the old Pennsylvania Road. Since its initial construction, the Lincoln Highway has taken several different routes through Pittsburgh and its environs.

The success of the Lincoln Highway led to other named routes across the country. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, construction was underway on the William Penn Highway, crossing the state via Pittsburgh, Harrisburg and Allentown. After nearly a century of decline, the National Road would find new life with the advent of the automobile and “motor-touring” in the 1910s and 1920s. The presence of the automobile on the National Road rejuvenated the towns along the road once again. The National Road again served as a major east–west route until the Pennsylvania Turnpike and the interstate system drew traffic away from the National Road.

Lincoln Highway marker and two former alignments of the Lincoln Highway in North Huntingdon Township, Pennsylvania. ASCE Pittsburgh Section.

The Federal Highway Act of 1921 created “an adequate and connected system of highways, interstate in character,” as well as the numbering system for highways. In Pennsylvania, the National Road was revived as US Route 40, the William Penn Highway as US Route 22 and the Lincoln Highway as US Route 30. These three routes provided vital east–west routes for motorists and trucks in Western Pennsylvania. While vital, these routes were tough on the vehicles of the day, as they crossed the tops of mountains, and vehicles would often need to stop to cool down. Perhaps the most famous rest stop was the S.S. Grandview Ship Hotel along the Lincoln Highway in Bedford County. Built in the shape of a ship, the hotel boasted a view of three states and seven counties. The Ship Hotel stood until 2001, when it was lost to a fire.

Although these routes crossing the Appalachian Mountains were a vast improvement for travel across Pennsylvania, as vehicular technology improved and ownership increased, the demand for a modern highway connecting the east and the west grew. To meet this demand, attention was turned to history and the failed South Penn Railroad of the 1880s. The South Penn Railroad and William H. Vanderbilt of the New York Central Railroad intended to provide a direct railroad route with a gentle grade connecting east with west as direct competition with the Pennsylvania Railroad. Construction abruptly ended due to a deal brokered to preserve the territorial rights of both the Pennsylvania Railroad and the New York Central Railroad, and the unused railroad grade and the partially built tunnels sat undisturbed for half a century.

Original western terminus of the Pennsylvania Turnpike, Irwin, Pennsylvania. ASCE Pittsburgh Section.

Formed in 1935, the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission began turnpike construction on October 26, 1938, and opened the route along the South Penn Railroad grade on October 1, 1940. The 160-mile highway connected US 30, the Lincoln Highway, at Irwin, Pennsylvania, outside Pittsburgh to US 11 at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, outside Harrisburg. The design was unique, modern and innovative. The grade-separated, limited-access toll highway provided quick and efficient access through the mountains connecting Pennsylvania’s east and west like never before. It would be dubbed “America’s first superhighway.” The highway, its service plazas and its seven tunnels quickly captured the imagination of the nation and was commemorated in story, song, souvenirs and postcards. The Pennsylvania Turnpike was later extended from the Delaware River at the New Jersey border to the Ohio border. The Pennsylvania Turnpike blazed the way for toll roads in other states and eventually became a component of a series of toll roads that connected New York City and Chicago. The interstate system followed in 1956, with many of the Pennsylvania Turnpike’s design features included.

GRAND BOULEVARDS

While the technology of highways and automobiles quickly improved in crossing the Alleghenies in the early twentieth century, the advent of the automobile also presented challenges to the existing city streets, which were designed for pedestrians, horse carts and streetcars. The City of Pittsburgh and the County of Allegheny needed to think big to accommodate the modal shift from human- to automotive-scale transportation.

As industrial development ensued, city engineer Edward Manning Bigelow made sure that Pittsburgh partook in the City Beautiful movement, an urban planning and architectural philosophy popular during the Victorian era that sought to make urban design beautiful as well as functional. After persuading Mary Schenley to donate the land for a large park in the city’s east end, Bigelow knew that a boulevard connecting the new park to downtown was essential. This led to the development of Grant Boulevard, a low-grade boulevard connecting the park with downtown along the city’s Bedford hillside early in the twentieth century. Today, Grant Boulevard is known as Bigelow Boulevard, named after the engineer who developed it. While Grant Boulevard was born from the City Beautiful movement, the need for future boulevards would be driven by age of the automobile. Beginning in 1920, a more direct route, Monongahela Boulevard, would be constructed connecting Schenley Park and east end neighborhoods with downtown. Monongahela Boulevard was later renamed the “Boulevard of the Allies” in dedication to the Allies of World War I.

Statue of Edward Manning Bigelow in Schenley Park, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. ASCE Pittsburgh Section.

Decorative monument along the Boulevard of the Allies, downtown Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. ASCE Pittsburgh Section.

In 1910, Pittsburgh’s Committee on City Planning commissioned a report by renowned landscape architect and city planner Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. to develop a plan to “meet the City’s present and future needs.” The report detailed technical approaches on appropriate roadway widths and specific thoroughfares that should be developed to meet the challenges of the city. Much of the report focused on the need to develop gentle-grade roadway solutions to improve mobility in an era of horse-cart transportation. One of the report’s recommendations was to eliminate Grant’s Hill, or the “Hump,” in downtown Pittsburgh. Olmsted’s “Hump Cut” was carried out in 1912 to minimize the grades of crucial downtown streets by lowering some streets by as much as sixteen feet. Remaining buildings in this section of downtown showcase the architectural anomaly of having to lower their entrances to the new street level. A fine example is the rear entrance to the Allegheny County Courthouse on Ross Street. Olmsted scoured the world for examples of how to develop thoroughfares to tackle Pittsburgh’s complex terrain and drafted a report recommending improvements to the waterfront and utilizing hillsides for important roadways. In addition to widening many of the city’s main streets, the report recommended many improvements and several new arteries that would come to fruition.

Ross Street rear entrance of the Allegheny County Courthouse showing the architectural adjustments required as a result of the “Hump Cut.” ASCE Pittsburgh Section.

Stone pylons along the Allegheny River Boulevard in Verona, Pennsylvania. ASCE Pittsburgh Section.

In an effort to connect the South Hills to downtown, Olmsted’s proposed South Hills Artery would utilize a high-level bridge and tunnel, which today is known as the Liberty Bridge and Tunnel. The report even provided details arguing the advantage of a low-grade bridge and tunnel in reaching the South Hills at a significantly higher elevation, thus reducing travel on steep roadways. The report details scores of other improvements to the city’s streets. Some were developed and some forgotten, but much of the city’s backbone known today can be attributed to Olmsted’s plan, connecting and improving on the city’s organic growth. Not to be left out of the City Beautiful movement, the county constructed its own grand boulevards—Allegheny River, Ohio River and Saw Mill Run Boulevards—connecting Pittsburgh with its surrounding environs. On some of these boulevards, the county placed stone pylons dedicating the routes with ornate stone carvings. Several can still be seen along the Ohio River and Allegheny River Boulevards.

PARKWAYS AND INTERSTATE HIGHWAYS IN WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA

While the boulevards within Pittsburgh were a venerable early solution to getting high-speed vehicles in and around the city, they lacked connectivity and often ended abruptly, sending vehicles into the street grids. Efforts to improve access into the eastern suburbs began in the 1920s with plans to upgrade Second Avenue and, later, to extend the Boulevard of the Allies. In 1937, a delegation of state officials drove the route from Churchill to Campbells Run Road, west of Pittsburgh. After they experienced difficulties traveling through Pittsburgh, they agreed to develop the Penn-Lincoln Parkway to supersede the arterial Penn and Lincoln Highways. Robert Moses, who planned New York City’s parkway network, was consulted on the project. His influence can be seen in the parkway’s design, notably the mindful route choice through topography that would guarantee a park-like environment, as well as the complex interchange layouts along the Penn-Lincoln Parkway.

Ground was broken for the parkway in 1946, a full decade before the interstate system was created. The east–west route includes two dual-bore tunnels (Squirrel Hill and Fort Pitt), with two traffic lanes in each, and a dual-level major river crossing, the Fort Pitt Bridge. The last link to be completed was the Fort Pitt Tunnel, which opened in 1960, connecting Monroeville to the Greater Pittsburgh Airport. The Penn-Lincoln Parkway has a complex history of naming and route numbering. From the Point to Monroeville, the route is colloquially referred to as the “Parkway East.” Likewise, the route from the Point to the airport is known as the “Parkway West.” As interstate designations appeared on the route, the parkway’s original namesakes, William Penn and Abraham Lincoln, have been obscured with time.

Penn-Lincoln Parkway East as seen from the Shrine of the Blessed Mother in South Oakland, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. ASCE Pittsburgh Section.

The Penn-Lincoln Parkway has carried many interstate designations, including I-70. The Point was also the original end of I-76, which, at the time, left the Pennsylvania Turnpike at Monroeville and was routed along the Parkway East into the city. The Parkway East became I-376 when I-76 was reassigned to follow the turnpike into Ohio. I-79 was planned to be routed along the Parkway West and along a yet-to-be-built Parkway North, while I-279 was intended to bypass the city to the west. After construction of the western bypass was completed in 1976 and it was the clear the Parkway North construction would be stalled, the route numbers were reassigned. I-79 bypassed the city to the west, and I-279 provided a loop through Pittsburgh with the completion of the Parkway North. The Parkway North and its reversible HOV (High Occupancy Vehicle) lanes opened in 1989, completing the loop and the route number swap. In 2009, to extend the interstate system past Pittsburgh International Airport, the numbering was again changed. I-376 would be extended along the Parkway West from the Point, past the airport, to end at I-80 outside Sharon, Pennsylvania. At this time, I-279 was also truncated at the Point.

While roads and highways will continue to play a critical role in Pittsburgh’s transportation network, it remains to be seen how advances in technology, such as vehicle automation, will shape the roads and highways of the future.