The South Eighteenth Street Stairs, in the South Side Slopes neighborhood. ASCE Pittsburgh Section.

PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION

Mobility for All

By Jason Machuga, PE, and Carrie Machuga

PUBLIC STAIRCASES

Walking: the most basic form of transportation. As such, walking in the public right-of-way is the most basic form of public transportation. In Pittsburgh, because of the city’s complex topography, with its steep hills and deep valleys, the pedestrian has been afforded a unique solution: the public staircase. According to Bob Regan in his book Pittsburgh Steps, “These city steps were, in essence, the city’s first mass transportation system.” Like any successful public transportation system, public staircases have played an important role in the development of Pittsburgh by connecting people within and between neighborhoods, as well as to and from school, employment, shopping and other daily activities. Pittsburgh’s some seven hundred public staircases have left their mark on the city and its neighborhoods and still perform their original purpose, even though much of the traffic has been displaced to other transportation modes.

Pittsburgh’s public stairs have several interesting features. Some staircases are actually streets in themselves, maintained by the city. Many even have their own street sign, like Mann Street at the intersection of Woodruff Street. There is even a set of public staircases that meet, creating a car-less intersection just the size of a landing on a wooded hillside. There are many houses within the city that are only accessible by public staircases. Take a field trip (virtual or terrestrial) to Bering Street on Pittsburgh’s South Side to see houses with their stoops connected directly to the public staircases.

The South Eighteenth Street Stairs, in the South Side Slopes neighborhood. ASCE Pittsburgh Section.

Yard Way Stairs “street” sign, in the South Side Slopes neighborhood. ASCE Pittsburgh Section.

Time, lack of funding and disinterest have taken their toll on many of these staircases, but recent public awareness efforts have, in some cases, protected them. The annual autumnal event “Step Trek” in Pittsburgh’s South Side has generated much interest and has led to rehabilitation of several staircases. Additionally, permanent wayfinding signs were recently installed for the “Church Route,” which created a route linking several staircases in the South Side neighborhood.

INCLINES

Pittsburgh’s topography produced a second specific public transportation solution: inclined planes—or, colloquially, the “inclines.” Two counterbalanced railcars ride on two adjacent parallel sets of track placed at a constant slope or incline in order to traverse large changes in elevation. At the peak, the city of Pittsburgh had numerous inclines. Only two remain: the Monongahela Incline and the Duquesne Incline. Both ascend the slopes of the Mount Washington and Duquesne Heights neighborhoods, respectively, and are nearly one mile apart. Both were designed to be near bridges that provided walking or streetcar connections to the city.

The Duquesne Incline was built by prominent local resident Kirk Bigham, who lived atop Coal Hill, as Mount Washington and Duquesne Heights were then known. While this region has geographic proximity to downtown Pittsburgh, it is separated by the Monongahela River and a four-hundredfoot vertical precipice. In a time before automobiles, Mr. Bigham had the foresight to see that in order to unlock the potential of this elevated land, a transportation solution must be developed to overcome the condensed contours. He hired Samuel Diescher, who designed and built the incline for a sum of $47,000. Diescher, who was born in Budapest and educated in Germany and Switzerland as a civil and mechanical engineer, designed many of the inclines in the United States. The Duquesne Incline opened to revenue service on May 20, 1877, providing a much-needed connection between Coal Hill, the Point Bridge and downtown.

After eighty-five years of service, the Duquesne Incline was shut down in 1962. Much like Mr. Bigham before them, the residents of Mount Washington and Duquesne Heights banded together to save the incline. It reopened in 1964 and is now operated by the Society for the Preservation of the Duquesne Heights Incline. This nonprofit organization not only continues to provide the crucial transportation link for Mount Washington residents but also provides an educational museum and a unique experience to the throngs of tourists who visit this iconic symbol of Pittsburgh. While the cars are not the originals, they are among the oldest operating transit vehicles in the country.

The nearby Monongahela Incline opened on May 28, 1870, and is the only other operating incline remaining in Pittsburgh. Unlike the Duquesne Incline, this incline is operated by the Port Authority of Allegheny County (PAAC). When riding on the incline, one can look to the east and see foundations from a parallel incline, the Monongahela Freight Incline, which operated from 1884 to 1935. These sister inclines worked in concert to provide a quick lift for people and freight. There is a still-functioning freight incline in nearby Johnstown, Pennsylvania, at Yoder Hill. Passengers can drive their automobiles onto the incline to ride up the 70.9 percent grade.

Duquesne Incline Lower Station, with vehicle departing station. ASCE Pittsburgh Section.

Pittsburgh had another pair of sister inclines: the Castle Shannon Incline and the Castle Shannon South Incline. But unlike the Monongahela passenger and freight inclines, these inclines operated in series rather than parallel. The Castle Shannon Incline carried passengers along the front face of Mount Washington, and then passengers would disembark, cross the street and transfer to the Castle Shannon South incline, which would take passengers along the backside of Mount Washington, where many of them transferred to the trolleys to take them into the South Hills neighborhoods and boroughs, such as Castle Shannon.

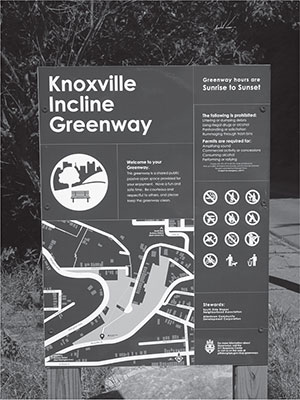

The Knoxville Incline, Pittsburgh’s famous incline with the bend, traversed the South Side Slopes to connect Pittsburgh’s Allentown neighborhood with the South Side Flats. Operational from 1890 to 1960, a sharp curve allowed the incline to navigate the natural topography of the valley from which it rose. Although this incline suffered the same fate as most of Pittsburgh’s inclines, it has been given a new life in an unexpected way. Portions of the former right-of-way of the Knoxville Incline have been converted into a park. With the help of the community, the site has been cleaned, an original bridge painted and it is now ready to be enjoyed as a quiet respite in a bustling city with a deep connection to its history.

Informational sign pertaining to the Knoxville Incline Greenway. ASCE Pittsburgh Section.

Rehabilitated bridge that formerly crossed the Knoxville Incline and is now part of the Knoxville Incline Greenway. ASCE Pittsburgh Section.

COMMUTER RAIL

Commuter rail also played an important role in serving Pittsburgh’s commuters for decades. Service was provided by several railroads, including the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O), Pittsburgh and Lake Erie Railroad (P&LERR) and the vaunted Pennsylvania Railroad (later Conrail and Norfolk Southern). Between them, there were several major stations or terminals in or near downtown Pittsburgh. The development of the city followed the railroad lines. The Pennsylvania Railroad line snaked through the east end, connecting East Liberty, Wilkinsburg and Edgewood with downtown. These communities are excellent examples of railroad-induced development. Commuter rail began to taper off as passengers began diverting to automobiles. Ironically, one of Pittsburgh’s last commuter trains, the “Parkway Limited,” was developed to divert passengers from the Penn-Lincoln Parkway East during a major reconstruction project. The “Parkway Limited,” a Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT) and Conrail operation, traveled between Pittsburgh and Greensburg, with various station stops along the way. The service was cancelled in 1981 after nine months of operation due to low ridership.

HORSECARS, CABLE CARS AND STREETCARS

Adapting rail technology to the region’s public right-of-way proved to be a challenge. Steam engines were not suitable in the street, but horsecar lines were an early solution. A hybrid of carriage and rail technology, horsecar lines provided smooth transportation when they were introduced in Pittsburgh in 1859. The first line was operated by the Citizens Passenger Railway connecting the Allegheny Cemetery in the Lawrenceville neighborhood with downtown.

The city’s hills once again proved to be a challenge, leading to the introduction of cable car technology in Pittsburgh’s East End neighborhoods in 1887. A steam engine was placed at the highest elevation along the line that drove a network of cables beneath the street. Each cable car would grip onto the cables and be pulled along the street, stopping by releasing the gripper from the cable and applying the brakes.

Cable cars were, however, quickly replaced by electric traction trolleys or streetcars. In 1890, Pittsburgh’s first electric streetcar began operation, powered by overhead catenary. Electric streetcars and trolleys offered faster speeds and longer ranges than horse and cable cars. The network quickly expanded, with many private companies developing lines and competing for riders. This technology quickly grew outside the city of Pittsburgh. In the early twentieth century, it was possible to travel by interurban electric trolley from Pittsburgh as far south as Fairchance, Pennsylvania, and as far north as Buffalo, New York. An interurban trolley line also connected Pittsburgh and Washington, Pennsylvania. Parts of this line have been restored and are operated at the Western Pennsylvania Trolley Museum. After World War II, interurban electric trolleys could not compete with advances in highway and vehicle reliability and convenience and were mostly abandoned.

Car no. 4398 at the Western Pennsylvania Trolley Museum. ASCE Pittsburgh Section.

In 1902, the Pittsburgh Railways Company was formed as a merger of several independent streetcar companies. The hub and spoke system carried passengers in all directions from downtown Pittsburgh. In 1937, the Pittsburgh Railway Company operated the first President’s Conference Committee (PCC) streamlined trolley used in revenue service in the United States. In 1950, the Pittsburgh Railway Company had more than one thousand cars; however, after World War II, ridership declined from 255 million passengers in 1947 to 66 million in 1962.

LIGHT RAIL TRANSIT

The PAAC commenced operations on March 1, 1964, and assumed operations of the bankrupt Pittsburgh Railways Company and many independent bus lines within Allegheny County. After the PAAC takeover of the streetcar/trolley network in Pittsburgh, the agency decided to abandon most of the routes. However, several routes into Pittsburgh’s South Hills neighborhoods and suburbs continued.

The existing lines were upgraded and converted into Light Rail Transit (LRT) in the 1980s and 2000s. However, as the network was being planned, the street-level tracks over the Smithfield Street Bridge and through downtown Pittsburgh were not deemed suitable for the LRT system. As a result, the LRT network in downtown was routed across the Panhandle Bridge (originally a Pennsylvania Railroad bridge), over the Monongahela River and then into tunnels below Sixth Street and Liberty Avenue. The downtown subway was constructed and opened in 1985. The subway was connected with an existing tunnel, formerly part of the Pennsylvania Railroad at the Steel Plaza Station near Grant Street in downtown Pittsburgh. The line then continues south over the rehabilitated Panhandle Bridge before joining the original routing of the Mount Washington Transit Tunnel just past Station Square.

Because the subway was constructed during the transition period from streetcar and trolley to the LRT, there are several unique features of the original design. The streetcars and trolleys owned by the PAAC at the time were President’s Conference Committee (PCC) cars, which, unlike LRT vehicles, could only travel in one direction. This meant that the system originally had trolley loops at both the Gateway Center and Penn Plaza termini, as well as a loop just outside the tunnel section to provide local downtown subway service. These loops have been removed now that all vehicles can run in both directions; however, a keen eye can still spot reminders of their presence, including the original Gateway Center Platform. The Wood Street and Steel Plaza stations have lower-level platforms, which are now closed but previously provided access to the PCC cars while they ran underground.

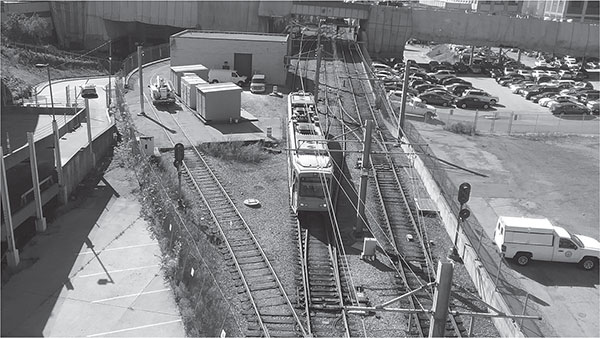

A light-rail vehicle traveling through the remains of a trolley loop before entering the downtown subway tunnel. ASCE Pittsburgh Section.

A light-rail vehicle stopped adjacent to the current high-level platforms; the abandoned low-level trolley platform can be seen to the right. ASCE Pittsburgh Section.

Stage I of the LRT conversion focused on the underground subway and upgrading the Beechview and South Hills Village Lines. The Overbrook Line was closed in 1993, ending operation of the PCC cars into the downtown subway. The Overbrook Line was reconstructed and reopened in 2004 under the Stage II LRT project. In 2012, the North Shore Connector opened, reconstructing the Gateway Station and extending the line under the Allegheny River to provide two new stations near the city’s baseball and football stadiums, as well as providing access to satellite parking and catalyzing new development opportunities near the stadiums and on the North Side.

BUSWAYS

In addition to the development of Pittsburgh’s light-rail network, the PAAC was a pioneer in the development of Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) in the form of the busway. A busway is a limited-access roadway exclusively for buses. Much like conventional rapid transit, a busway has stations and a spine line that serves all of the stations. Many of the stations provide bypass lanes, and there are ramps along the busways where buses can enter and exit. The busways are well suited to provide express bus service and one-seat rides from locations throughout the region, providing a much-needed bypass of the traffic of the surface streets and highways.

Pittsburgh’s first busway, the South Busway, opened in 1977 and was among the first in the nation. The South Busway connects the Mount Washington Transit Tunnel with Glenbury Street in Overbrook, runs parallel to Saw Mill Run Boulevard (PA Route 51) and provides relief to the congestion along that corridor. The corresponding Mount Washington Transit Tunnel provides a bypass of the Liberty Tunnel for local and long-distance bus routes.

The Martin Luther King Jr. East Busway, which opened in 1983, connects downtown Pittsburgh with Swissvale, serving the city’s eastern neighborhoods and eastern and southeastern suburbs in Allegheny County. It was built within the original Pennsylvania Railroad Line right-of-way. Carrying a design speed of fifty-five miles per hour throughout most of the corridor, a trip from Wilkinsburg to downtown was reduced from forty-five minutes to fifteen. As a result, the Martin Luther King Jr. East Busway has seen average daily ridership as high as thirty thousand.

Photo of a SkyBus on display outside Bombardier, at 1501 Lebanon Church Road, Pittsburgh. ASCE Pittsburgh Section.

The West Busway, added in 2000, provides a bypass of the congested Parkway West and Fort Pitt Tunnel by connecting the Parkway in Carnegie with West Carson Street in the South Side. The original plan included extending the busway parallel to West Carson Street and constructing a new Monongahela River Bridge in conjunction with the Wabash Tunnel Project, but those elements were never built.

The Wabash Tunnel, originally built by the Wabash Pittsburgh Terminal Railway, was reopened as a High Occupancy Vehicle (HOV) tunnel connecting Saw Mill Run Boulevard with West Carson Street. After years of abandonment, the tunnel was purchased by the PAAC for the SkyBus Project, a sophisticated people-mover system developed by the Westinghouse Company to be built in the South Hills to replace the trolleys and streetcars. A demonstration line was constructed in South Park and ran for several years. Although the Skybus never gained traction, the technology developed locally at the Westinghouse Company, now Bombardier, has been used to provide public transportation solutions throughout the world. The Pittsburgh International Airport’s automated people-mover, built with the 1992 Airside & Landside Terminals, is a descendant of this technology. A SkyBus vehicle is still on display outside the Bombardier building.

SELF-DRIVING VEHICLES

The city of Pittsburgh is also a pioneer in robotics and self-driving vehicles. Eric Meyhofer, a founder of the Carnegie Mellon Robotics Institute, joined with Uber in 2015 to further develop the self-driving vehicle. Uber, which provides on-demand rides via its smartphone application, launched public rides in autonomous vehicles in Pittsburgh on September 14, 2016. The autonomous vehicles provide riders with point-to-point service with a driving monitor behind the wheel and a technician aboard.

Engineers from across many disciplines have played an important role in developing public transportation throughout the history of Pittsburgh. The significant innovations from inclined planes to people-movers and autonomous vehicle technology would not have taken place without a strong history of Pittsburgh supporting its engineers and Pittsburgh’s engineers supporting the city.