Greater Pittsburgh Wastewater History: A Journey through Time. A1 Applications, LLC.

WASTEWATER

Dealing with Water Pollution

By Uzair (Sam) Shamsi, PhD, PE

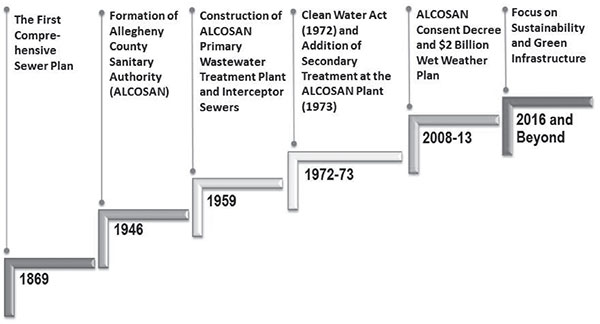

Wastewater engineering, a sub-discipline of civil engineering, involves conveyance and cleaning of wastewater (sewage) from residential, commercial, institutional and industrial customers. Wastewater collection and treatment is required for reasons of public health and safety to prevent discharge of untreated wastewater to water bodies and to minimize pollution of water bodies where treated wastewater is discharged. Civil engineers map out topographical and geographical features of land to determine the best means of wastewater collection. Civil engineers also study the flow rate (quantity) and characteristics (quality) of wastewater to design appropriate wastewater treatment plants. As such, civil engineers are responsible for planning, design, construction and sometimes operation of sewer systems and sewage treatment plants. This chapter presents a history of the Greater Pittsburgh region’s wastewater collection and treatment system. The image here presents a timeline of Pittsburgh’s regional wastewater history, which will be described in various sections of this chapter.

EARLY HISTORY

Greater Pittsburgh Wastewater History: A Journey through Time. A1 Applications, LLC.

Water is life! Water is the most precious natural resource on the planet because humans, animals and plants cannot survive without it. According to Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Authority (PWSA) website, the first documented effort to establish a public water system in Pittsburgh occurred in 1802, when the municipality had a population of about 1,600 persons. A history of Pittsburgh drinking water distribution and treatment systems is presented elsewhere.

From the early 1800s until around 1920, sewers in the city of Pittsburgh and surrounding communities were constructed to collect both wastewater and stormwater in a single pipe away from streets, businesses and homes and convey the combined flow directly to the rivers to reduce disease and flooding. Because the collection systems carried both stormwater and wastewater, they are called combined sewer systems. As early as 1930, the Pennsylvania Sanitary Water Board (PSWB) sought to compel Pittsburgh to submit a plan for a comprehensive sewage system. In December 1937, Pittsburgh mayor Cornelius Scully convened a meeting of Allegheny County municipalities to discuss possible collective action. The onset of World War II, however, delayed any action on sewage treatment. According to the 3 Rivers Wet Weather website, in June 1945, the PSWB issued the long-awaited orders to the City of Pittsburgh, 101 nearby municipalities and more than 90 Allegheny County industries to cease discharging untreated wastes into state waterways.

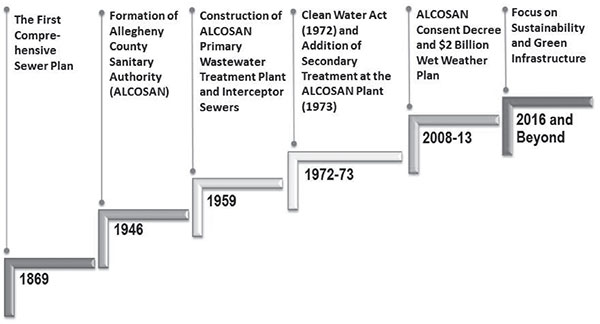

The image here shows an 1869 map of Allegheny City that accompanied the first comprehensive sewer plan report for the city (City of Allegheny, 1869). Allegheny City, now Pittsburgh’s North Side, was a separate city from 1840 to 1907. Allegheny City was annexed by the City of Pittsburgh in 1907. The sewer master plan references private sewers already built, indicating that some city sewers predate the water system, which is unusual in most cities. The plan also proposed using the route of the Pennsylvania Canal, abandoned in 1864, for a sewer line. Evidence of this sewer was discovered when the canal locks were excavated for I-279. The Historic American Engineering Record report for the sewer is available in collections at the Library of Congress.

At the turn of the twentieth century, Pittsburgh embarked on its largest infrastructure improvement campaign, building sewers, water lines, roads and power lines that created the city we know today. And over the past fifty years, numerous changes have taken place such that Pittsburgh, once known as the “Smoky City,” is now recognized as a center for advanced technology and research. A major part of these remarkable changes is the transformation of the area’s rivers and streams from open sewers to waterways that are safe for recreation and commerce.

The First Comprehensive Sewer Plan Map of the Allegheny City, 1869. Allegheny County.

PWSA

The modern-day Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Authority (PWSA) was created in 1984. It merged with the Pittsburgh Water Department in 1995 and became the sole proprietor of the sewer system in 1999. PWSA owns and operates the wastewater collection system within the city of Pittsburgh, but it does not have a wastewater treatment plant. Wastewater treatment for the city and surrounding municipalities is provided by a regional wastewater utility called the Allegheny County Sanitary Authority (ALCOSAN).

ALCOSAN

In 1946, the Allegheny County Sanitary Authority (ALCOSAN) was formed to study the needs of the region and to develop and submit a treatment plan to Pennsylvania Sanitary Water Board. Along with the construction of a treatment plant, about ninety-two miles of very large pipes (some as large as twelve feet in diameter), called interceptors, were placed along the major rivers and streams in the 1950s. These interceptors were designed to receive wastewater from municipal sewer systems and “intercept,” or redirect, the sewage to the ALCOSAN treatment plant, where, as required, it received primary treatment before reaching the waterways. Primary or physical/chemical treatment consists of temporarily holding the sewage in a sedimentation basin, where heavy solids can settle to the bottom while oil, grease and lighter solids float to the surface. The settled and floating materials are removed, and the remaining liquid may be discharged to receiving waters or subjected to secondary treatment. ALCOSAN’s primary treatment plant became fully operative in 1959.

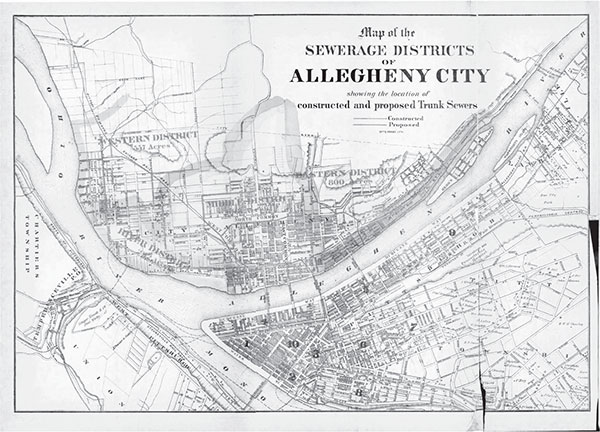

Located along the Ohio River on Pittsburgh’s North Side, about three miles from the Point State Park, ALCOSAN as of 2017 provides wastewater treatment services to a population of 836,600 (2010 census) in eighty-three municipalities, including the city of Pittsburgh. ALCOSAN’s fifty-nineacre Woods Run treatment plant, one of the largest regional wastewater treatment facilities in the Ohio River Valley, processes up to 250 million gallons of wastewater daily. The map in the image here shows the ALCOSAN wastewater treatment plant location and service area boundary.

ALCOSAN wastewater treatment plant location and service area boundary. A1 Applications, LLC.

In the ALCOSAN system, each municipality or municipal authority owns, operates and maintains its municipal satellite collection system. Whether in a combined or separate sanitary collection system, pipes in the system carry sewage from many individual homes to a large trunk sewer. The trunk sewer then carries the wastewater from multiple municipal collection systems to ALCOSAN’s interceptor sewer. The interceptors are a series of pipes that transport the wastewater on the final leg to the treatment plant. The interceptor system, buried up to 120 feet deep under the rivers, is sometimes referred to as the “deep tunnel system.” About thirty miles of ALCOSAN interceptors are deep tunnel interceptors that extend along and cross under the Allegheny, Monongahela and Ohio Rivers, with concrete pipe grouted into rock bore tunnels. Originally, all the interceptor sewers along both the main rivers and tributary streams were designed as traditional open-trench construction (shallow-cut) sewers. However, the interceptor sewer design along the main rivers, navigable waterways under the jurisdictional authority of the United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), was subsequently changed to a deep tunnel configuration. This decision was made because construction permits for traditional trench sewers along navigable rivers would only be issued with the stipulation that the interceptors would be subject to lowering or removal upon order from the USACE.

The following subsections describe the history of ALCOSAN based on a 2013 article by ALCOSAN historian Michael Anthony.

The Problem

Before the nineteenth century, the narrow tract of land now occupied by the ALCOSAN wastewater treatment plant on the north side of the Ohio River opposite McKees Rocks was primarily known as a pass-through to points west. The coming of the Civil War in 1861 spurred massive industrialization in Northern cities. The industrialization of this area played a common yet integral role in Pittsburgh’s early rise as the world’s workshop. By staging their industries along the region’s rivers, men like James Verner, Charles Schoen, Andrew Carnegie and Henry Clay Frick ensured convenient access to coal and other materials necessary to keep their factories and profits in motion. Rivers were viewed not as natural resources but as arteries to deliver natural resources and also discharge waste products as an integral part of the coal mining activities and the manufacturing processes of the glass, iron and steel industries that made Pittsburgh the “Iron City.” As a result, little concern was afforded when waterways, once teeming with life, became lifeless streams of disposal for those same factories.

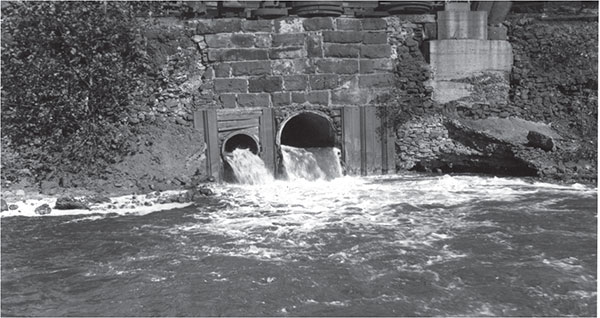

In the early 1900s, smoke billowing from factories blackened the midday sky and coated the city in tons of particulate matter. In addition, municipal and industrial waste, mine drainage and other pollutants led to poor water quality and the spread of disease. In 1907, Pittsburgh began sand filtration and chlorination of water supplies. At the same time, the city and hundreds of upstream communities continued to dump untreated sewage and industrial waste into the rivers. The image here shows an ALCOSAN photo circa 1940s, with sewage overflows into water. By the mid-1940s, less than 2 percent of the discharges into the Ohio River received any treatment at all, and the Monongahela River, void of aquatic life, ran red with acid mine drainage, mill effluent and other pollutants.

The election of Cornelius D. Scully as mayor of Pittsburgh in 1936 put a new emphasis on the environmental problems facing the city and the region. Scully was pressured by the newspapers to act in reversing the damage that years of industrial prosperity had wreaked on the condition of the city. He created the Commission for the Elimination of Smoke, opened new parks and concentrated on programs to provide the city with a cleaner water supply. With the coming of war in 1941, however, Scully was forced to put aside his campaign as the city’s factories refitted to supply the war machine. The region produced 95 million tons of steel, 52 million shells and 11 million bombs to supply the Allied effort, but the pollution that resulted turned the rivers into cesspools and the day sky into night.

Discharge of untreated sewage in 1940s. ALCOSAN.

The Solution

As the war neared an end, civic leaders once again took up reversing years of environmental destruction in the region. Richard King Mellon, president of the Pittsburgh Regional Planning Association, generated support for a postwar planning committee to serve as a coordinating mechanism for regional transportation and environmental improvement efforts. The Allegheny Conference on Community Development was thus incorporated in 1944.

Forming a partnership with newly elected mayor David L. Lawrence, Mellon used the Allegheny Conference as a vehicle to promote what would be known as the “Pittsburgh Renaissance,” a “growth coalition” of capital, labor and politics. The immediate goals of this powerful partnership included smoke abatement, flood control, renewal of the Golden Triangle business district and the establishment of a regional sanitation district.

In May 1945, two developments would move the county closer to addressing water quality issues. The Pennsylvania Municipal Authorities Act of 1945 provided for the incorporation of bodies with power to acquire, hold, construct, improve, maintain and operate, own and lease property to be devoted to public uses and revenues. These uses included transportation, bridges, tunnels, airports, sewer systems and sewage treatment works. Secondly, in the enforcement of PA Clean Streams Law of 1937, PSWB ordered 102 municipalities and 90 industries in Allegheny County to prepare preliminary plans and specifications for sewage treatment. The board further ordered cessation of sewage and industrial discharges by May 1947. At this time, raw sewage and industrial wastes flowed directly into the Pittsburgh waterways. Aquatic life and dissolved oxygen concentration in the Ohio, Monongahela and Allegheny Rivers were severely affected.

On March 5, 1946, the Allegheny County commissioners adopted a resolution creating ALCOSAN, with a plan to finance the agency through bond issues. Also in March, the authority was granted office space on the fifth floor of the City-County Building and use of the city’s testing laboratory on Centre Avenue.

Planning and Design

By mid-1946, ALCOSAN had begun conducting sewer inspections and weir sampling to determine the extent of the region’s sewage problems. This field work revealed previously unknown mileage, capacities and conditions of the county’s 102 municipal sewer systems; 35 sewer locations were selected for preliminary sampling, which included the participation of 59 municipalities and 15 industrial sites.

Planning efforts continued through the first half of 1947, and by September 24, ALCOSAN had submitted a plan to the United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) to lay interceptor sewers along the Monongahela, Allegheny and Ohio Rivers. Preliminary sampling was completed in November 1947. In all, an average flow of 65 MGD from a population of about 678,000 was measured, sampled and analyzed to determine the properties of wastewater discharge from municipal and industrial sewers. On February 9, 1948, ALCOSAN released a plan recommending an $82 million regional wastewater treatment plant for Pittsburgh and the surrounding communities. The planned conveyance system included ninety-one miles of interceptor sewers and sixty-five miles of trunk sewers. The plan was approved by PSWB in 1948, and by June 1950, ALCOSAN had begun preliminary test borings in the area of the treatment plant site. The cores showed a variety of subsurface conditions, including river silt, ash, coal screenings, sand and building foundations remaining from old structures.

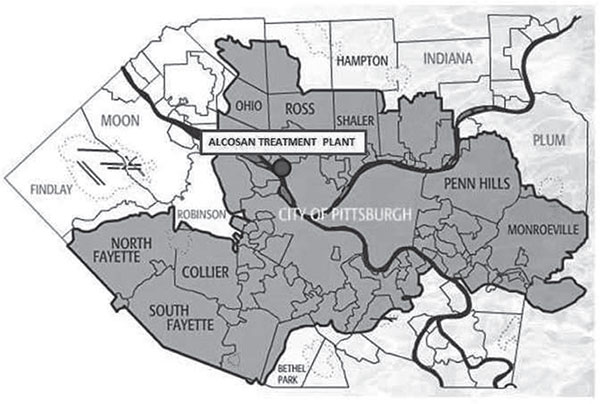

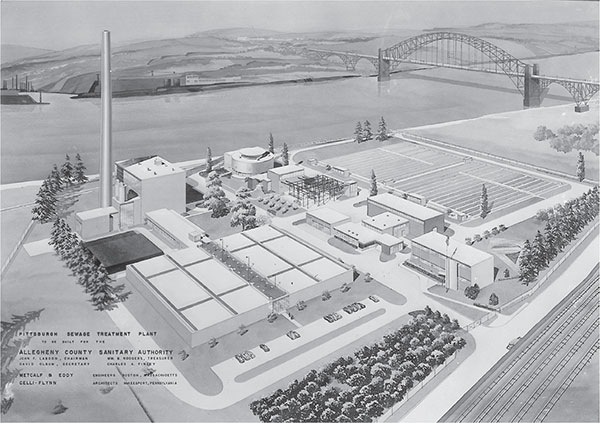

CONSTRUCTION

In 1951, ALCOSAN proceeded with planning for construction of the wastewater conveyance system and wastewater treatment by hiring Celli-Flynn of McKeesport as consulting architects for all ALCOSAN buildings and Michael Baker Jr. Inc. of Rochester to make soundings for eight interceptor river crossings. Plans and specifications for the treatment plant were completed by the consulting engineers Metcalf & Eddy in August 1953. The image here shows an architectural rendering of that treatment plant. Beginning in December 1955, ALCOSAN received bids for the first construction contracts. In all, $50 million worth of contract bids were opened through the month of December. In addition, all 343 property owners involved in required rights-of-way were contacted by year’s end, with 26 properties expected to require condemnation proceedings.

Architectural rendering of the ALCOSAN Primary Treatment Plant, constructed in 1959. Celli-Flynn Brennan Architects.

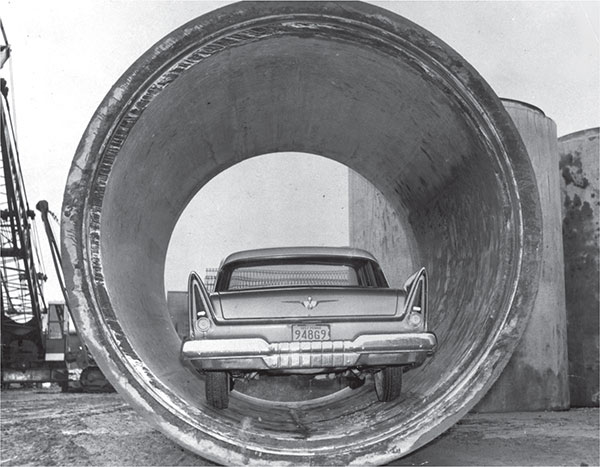

ALCOSAN interceptor sewer pipes, constructed in 1950s. ALCOSAN.

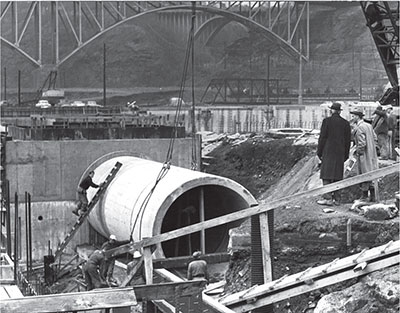

Treatment plant construction began in March 1956. Contractors from Dravo Corporation began preparatory work for construction of the main interceptor, which ran along the main rivers. Workers began constructing concrete access shafts at Thirty-Sixth Street opposite Herr’s Island and at Belmont Street just upstream of the West End Bridge. The images here show the large underground concrete pipes used for interceptor construction along the Ohio River and construction of an ALCOSAN deep tunnel interceptor.

In April 1957, Dravo Corporation completed construction of the river wall at the plant site, the first contract to be completed under the ALCOSAN plan. Construction of the treatment facilities continued through the winter of 1958 and into the spring of 1959. On April 30, bulkheads were removed from individual outfall connections, and the system was put into operation as a primary treatment plant. Initial operational difficulties included the formation of football-sized grease balls and odor from the plant chimney.

Sewer line installation near the Ohio River in 1957. ALCOSAN; Weisberg, 2011.

Construction of an ALCOSAN deep tunnel interceptor sewer. ALCOSAN; ALCOSAN, 2012.

As ALCOSAN executive director and chief engineer, Mr. John F. Laboon supervised the design and construction of the plant. Considered the father of ALCOSAN, he was an internationally famous sanitary engineer. In 1960, Laboon was named Engineer of the Year by the Pittsburgh Section of ASCE, and in 1969, he was elected an honorary member of ASCE. Speaking at a public hearing on May 14, 1958, regarding the discharge of wastes in the sewer system, Laboon stated that the Allegheny River would be fishable water again within six months of the system going into operation.

In 1960, ALCOSAN was nominated for the Outstanding Civil Engineering Achievement Award by ASCE. The recognition served as a fitting punctuation for the successful planning, design, construction and initial operation of ALCOSAN’s collection and treatment system and would set an indicative tone for the authority’s progression and expansion into the future.

The Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1948 was the first major U.S. law to address water pollution. Growing public awareness and concern for controlling water pollution led to sweeping amendments in 1972. As amended in 1972, the law became commonly known as the Clean Water Act (CWA). The 1972 amendments established the basic structure for regulating pollutant discharges into the waters of the United States. CWA prohibited the discharge of pollution into waterways unless a permit had been secured. It also required secondary (biological) treatment at wastewater plants. ALCOSAN proactively started the design of secondary treatment processes in the late 1960s, and operation of the secondary treatment plant commenced in 1973.

In 1973, the Pittsburgh Section of ASCE recognized ALCOSAN with the Section’s Civil Engineering Achievement Award for sanitary system design and construction.

CHALLENGES

Civil engineers faced challenges during the design of the ALCOSAN treatment plant and the interceptors related to geotechnical investigations and hydraulics, as these structures were being built for the first time to satisfy the regulatory mandates. The engineers did not have computers and modeling software at that time, so design calculations had to be done manually. The main contribution of civil engineers to wastewater control in Allegheny County was to design these complex hydraulics structures from scratch without existing handbooks and design manuals. Another challenge was political rather than technical. The commonwealth mandated wastewater treatment, but the elected representatives resisted, as a reflection of public resistance to pay the costs.

RECENT PAST (1992–2012)

By 1992, ALCOSAN had begun addressing the growing concern over sewer overflows and wet weather pollution control. In 1994, ALCOSAN started planning for permit requirements as required by the Clean Water Act and the EPA’s Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) Control Policy.

From 1995 to 1999, ALCOSAN worked with federal and state environmental regulatory agencies to negotiate a consent decree that would satisfy ALCOSAN’s obligations under environmental law to comply with the Clean Water Act and U.S. EPA CSO Control Policy. The consent decree received final approval in January 2008. The decree required that ALCOSAN prepare and implement a Wet Weather Plan (WWP) to repair broken sewer lines, reduce inflow and infiltration, reduce the frequency and amount of CSOs and eliminate Sanitary Sewer Overflows (SSOs) by 2026. The WWP report was released by ALCOSAN in 2012.

ALCOSAN’s present wastewater treatment plant showing secondary clarifiers. ALCOSAN.

From 2000 to 2012, ALCOSAN completed a $400 million capital improvement program, which addressed odor control, treatment capacity, solids handling and wet weather planning. The secondary treatment clarifiers are located at the bottom of the photo. The image here shows a recent photo of the ALCOSAN wastewater treatment plant.

PATH FORWARD: 2016 AND BEYOND

Pittsburgh owes its existence to the meanders and confluence of three great American rivers. The Allegheny, Monongahela and the Ohio Rivers are a point of pride and are integral to the city’s identity. As the city continues its historic transition from a riverfront industrial superpower to an education and research mecca, the quality of our rivers and riverfronts is of paramount importance.

In 2016, ALCOSAN started design of Phase 1 of its Wet Weather Plan, which is considered to be the largest public works project in the region’s history, through $2 billion in engineering and construction projects.

The first canon of the ASCE’s 2014 Code of Ethics emphasizes sustainable development: Engineers shall hold paramount the safety, health and welfare of the public and shall strive to comply with the principles of sustainable development in the performance of their professional duties.

Green Infrastructure

The Pittsburgh wastewater community and civil engineers are now considering sustainable alternatives in addressing local and regional wet weather issues. Since 2015, the wastewater treatment emphasis in the Greater Pittsburgh region has shifted from conventional gray infrastructure to sustainable infrastructure. Gray infrastructure is brick, mortar and concrete construction such as pipes, tunnels and storage tanks. Because ALCOSAN wastewater includes both sewage and stormwater runoff, its volume can be reduced by reducing the stormwater component. When green infrastructure is used for reducing stormwater entering a sewer system, it is referred to as green stormwater infrastructure (GSI). As noted by Shamsi (2017), GSI such as rain gardens, green roofs and porous pavement is considered sustainable because it uses natural processes such as infiltration and evaporation to capture stormwater runoff close to its source at distributed (decentralized) locations throughout a watershed. In some locations, GSI can be a cost-effective, sustainable and environmentally friendly way to manage the volume, rate and water quality of stormwater runoff entering the sewer system and waterways while providing additional benefits to communities. More than one hundred years ago, when combined sewers were constructed in Pittsburgh, they were perceived to be a cutting-edge gray infrastructure solution. Pittsburgh region is now spending billions of dollars to fix the CSO problems of that inadequate gray system. Likewise, GSI is not a panacea and should be planned, designed, constructed and maintained carefully for effective CSO control.

Pittsburgh is now riding the green wave. In 2016, ALCOSAN changed its logo to reflect its green infrastructure focus and launched a multimillion-dollar Green Revitalization of Our Waterways (GROW) grant program. The GROW program provides grants to green infrastructure and other source reduction projects for the eighty-three Allegheny County municipalities, including the city of Pittsburgh, that are served by ALCOSAN. The program has offered $19 million in grants for fifty-nine projects since January 2017.

Pittsburgh Green Wave at ALCOSAN and PWSA. ASCE.

In 2016, Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Authority (PWSA) completed a draft of a City-Wide Green First Plan that looks at ways to keep the Pittsburgh rivers clean while creating great community-focused infrastructure for a maturing city. The draft plan examines the existing stormwater conditions that will guide where green infrastructure will be installed to achieve the most cost-effective and beneficial results to the residents of Pittsburgh. PWSA expects to implement the recommendations of this plan by 2032 by achieving the goal of managing 1,835 acres of impervious surface using green infrastructure practices. The image here shows conceptual rendering for PWSA’s GSI Park in the Upper Hill District neighborhood. It is currently scheduled for completion in the spring of 2018. The project will manage more than 1 million gallons of runoff.

Wastewater Infrastructure Report Card

Every four years, the ASCE Report Card for America’s Infrastructure depicts the condition and performance of American infrastructure in the familiar form of a school report card—assigning letter grades based on the physical condition and needed investments for improvement. As shown in the image here, the 2017 Infrastructure Report Card grades the national wastewater infrastructure as a “D+.” Although the current grade shows a slight improvement from the 2013 grade of D, it is essentially the same as in the first report card issued in 1998. To raise the grade, the 2017 infrastructure report suggests, among other things, renewed or enhanced federal and state aid and supporting green infrastructure.

In addition to national infrastructure, ASCE also grades the state infrastructure. The latest Pennsylvania Report Card was released in 2014. Unfortunately, at a D-, Pennsylvania’s 2014 wastewater grade is below even the national wastewater grade, mostly due to relatively higher number of combined sewer overflows (CSOs). In fact, Pennsylvania has the highest number of CSOs of any state. The Pennsylvania wastewater infrastructure report indicates that aging wastewater management systems discharge billions of gallons of untreated sewage into Pennsylvania’s surface waters each year. The commonwealth must invest $28 billion over the next twenty years to repair existing systems, meet clean water standards and build or expand existing systems to meet increasing demands. Improving CSO infrastructure could cost $20.8 billion based on applying reported costs from Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and the City of Lancaster to the remaining 151 cities with CSO. While investment needs are estimated to cost eighty-seven times the cost of the Pittsburgh Penguin’s CONSOL Energy Center, funding has decreased. The Pennsylvania Infrastructure Investment Authority’s (PENNVEST) budget in 2013 for grant and loan awards for sewer projects is $335 million, less than 25 percent of the required annual investment. As noted by ASCE, in 2014 Pennsylvania’s appropriation from the Federal Clean Water Act also decreased to $53 million.

2017 ASCE Infrastructure Report Card.

Regarding hydraulic fracturing for oil and natural gas drilling and production, the 2014 Pennsylvania infrastructure report indicates that at the onset of the surge in unconventional drilling in 2008, Pennsylvania’s infrastructure was inadequately prepared to deal with the unique challenges of this new drilling technique. This resulted in frac water disposal at wastewater treatment facilities not equipped to handle the high total dissolved solids (TDS) in the waste stream. On April 19, 2011, Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (PADEP) issued a “Call to Action” letter to all gas drilling operators to cease, within thirty days, delivering this wastewater to facilities that had been accepting the water under special provisions of the commonwealth’s regulations that exempted these facilities from TDS treatment requirements. Since this Call to Action, ASCE in 2014 reported that the percentage of wastewater going to treatment facilities has decreased from 57 percent to 16 percent, and the amount of on-site reuse of frac water has increased from 31 percent to 74 percent.

Although ASCE does not grade local infrastructure, the Greater Pittsburgh wastewater grade is expected to be close to the state grade of D- due to high number of CSOs. This poor grade indicates a compelling need for reinvestment to maintain and upgrade the existing wastewater systems in the Pittsburgh region.