Why was the Ardennes area so important to Hitler’s plans? The Eastern Front was too extensive and the Soviet armies were too large for Germany to force an endgame in the east. While the Wehrmacht could afford to give up territory in the East, Hitler knew he would never be able to negotiate with Stalin. The Western Front was small enough for decisive action and Germany could not afford to lose the Ruhr, its industrial heartland, and the Allied armies were getting closer. The West Wall, a line of fortifications along its western border, was also an ideal position to hold with a thin crust of troops, allowing reserves to concentrate for the counteroffensive.

Hitler wanted to break through and then turn north, driving a wedge between the British and American armies. The advance would isolate British 21st Army Group in Holland from 12th U.S Army Group in Belgium, removing the threat to the Ruhr. The final objective was the port of Antwerp, which would be the Allies’ main point of entry for supplies in Europe once the River Scheldt was opened to shipping. Its seizure would severely weaken SHAEF’s situation on the Western Front and then negotiations with the Allies could begin. At least that was Hitler’s plan.

By the middle of September it was an overstretched supply line rather than Rundstedt’s capabilities or the tenacity of the German soldier which brought the Allied advance to a halt in front of the West Wall. While SS panzer divisions could be withdrawn immediately from the line, OKW West estimated that it would take until the end of October to withdraw the rest of the troops from the line. On hearing the news, Hitler set the target date for the attack as 1 November and he made it clear to Rundstedt that no ground must be given up in the meantime. It was a tall order for the new Commander in Chief.

By September 1944 Germany had suffered over three million military casualties and untold millions of civilian casualties. The Third Reich’s cities and industries were under constant air attack but Reich Minister Albert Speer was working on expanding the economy. The people carried on working in spite of the devastation but while new factories sprung up in the countryside it was becoming increasingly difficult to meet the Armed Forces’ needs. It seemed that only Hitler was optimistic about the Third Reich’s capabilities to launch an offensive in the West.

Rundstedt must have wondered where the troops would come from to launch such an ambitious attack but plans were already underway to find them. On 19 August Hitler instructed Walter Buhle, OKW’s Army Chief of Staff, and Speer to organise enough men and materiel for the November offensive. Heinrich Himmler was also appointed head of a new ‘Replacement Army’ and he assembled eighteen new divisions and ten panzer brigades by taking men from the military staff and the security services. Although only two of the divisions were sent to the Western Front most of the new tanks, assault guns and artillery manufactured in the summer were sent west.

Hitler had to adjust the timing of the attack until late November to allow the recruitment of another 25 new divisions for an ‘operational reserve’. OKW assembled many by recalling units from the Balkans and Finland to the Western Front. Joseph Goebbels also instigated a ‘comb-out program’, expanding the conscription age limits while lowering medical standards for men recovering from battle injuries.

The Navy and Air Force were also combed for able-bodied men and even the Nazi Party faithful who had so far avoided military service were called up. Employment exemptions were rechecked, new non-essential jobs were announced and many industries and agriculture were investigated with a view to replacing workers with concentration camp inmates.

Hundreds of thousands of new conscripts were found and then formed into new Volks Grenadier Divisions rather than strengthening existing formations on Hitler’s insistence. The expanding Wehrmacht was looking impressive on paper but many divisions were below strength or short of tanks, transport, artillery and all kinds of equipment. The problem was that Hitler believed they were all at full strength and anyone who disagreed was accused of defeatism or treason.

By the time Hitler made his announcement on 16 September, his paranoia had led him to be involved in every major military decision, even getting involved in detailed planning. However, the role of the Wehrmacht’s Chief of the Operations Staff must not be underestimated. Jodl turned the Führer’s ideas into military plans and then made sure they happened. He also represented the Wehrmacht commanders, presenting their suggestions and objections to Hitler.

Although the German generals dare not speak out against Hitler, in private they were scathing of his plans for the Ardennes Offensive. Rundstedt later admitted that ‘all, absolutely all, conditions for the possible success of such an offensive were lacking.’ Field Marshal Model’s reaction was blunter; ‘This plan hasn’t got a damned leg to stand on.’

Around 25 September Jodl was ordered to turn Hitler’s idea for a counteroffensive into an operational plan. The plan had to fulfil eight objectives:

1 The attack would be launched by Field Marshal Walter Model’s Army Group B

2 The attack would be made in the Ardennes in late November

3 Success depended on secret planning, tactical surprise and a speedy advance

4 The initial objective was to cross the Meuse River between Liège and Namur

5 The final objective was to capture Antwerp, cutting the Allied line in two

6 Two panzer armies would spearhead the attack with an infantry army on each flank

7 The attack would be supported by the Luftwaffe and many artillery and rocket units

8 The plan was to destroy the British and Canadians north of the line Antwerp – Liège

The Chief of the OKW, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, was hardly involved in the planning while Rundstedt was kept in the dark. Jodl did all of the work and came up with five alternatives:

1 Operation Holland: single-thrust from Venlo towards Antwerp

2 Operation Liège-Aachen: a double northwest thrust from northern Luxembourg and Aachen

3 Operation Luxembourg: a double attack from central Luxembourg and Metz towards Longwy

4 Operation Lorraine: a double attack from Metz and Baccarat towards Nancy

5 Operation Alsace: a double attack from Epinal and Montbeliard towards Vesoul

Operation Liège-Aachen was chosen and the main drive would be made through the Ardennes and Eifel areas. This double-pronged attack became known as the Big Solution. Jodl presented the outline plan on 19 October and three days later representatives from Rundstedt’s and Model’s forces were briefed about the operation at the Wolf’s Lair.

Jodl’s plan had Fifth Panzer and Sixth Panzer Armies leading Army Group B’s attack while Seventh Army advanced in echelon on the south flank. Hitler promised eighteen infantry and twelve armoured (or mechanized) divisions and Hermann Göring promised maximum support from the Luftwaffe. Preparations had to be complete by 20 November ready to attack five days later. The timing was based on the high possibility of ten days of bad weather, in the hope it would cancel out Allied air supremacy.

Army Group B’s commander, Field Marshal Walter Model.It could be argued that Hitler could have transferred troops from the Eastern Front or shortened the Western Front to release men; he refused to do either. He was adamant that Antwerp was the goal and it had to be taken with his initial estimate of around thirty divisions.

The winter of 1944-45 was one of the coldest in living memory and American, British and German troops suffered in the terrible conditions; civilian refugees did too. Private Thomas O’Brien of the 26th Infantry Division tucks into his C Ration in a snow-covered field. (NARA 111-SC-198483)

Hitler had personally selected all Wehrmacht generals following the July Plot, choosing officers who were either subservient or hardened Nazis. None would, or even could, stand up against the Führer and he viewed their proposals and protests with suspicion. He was also involved in decision making at all levels and nothing could be changed without his permission, not even the movement of individual divisions.

While Rundstedt was an old school military general, Army Group B’s commander, Field Marshal Walter Model, was a younger, politically motivated general. Relations between the two were frosty but they dealt with military matters in a workmanlike manner. However, the Führer’s interference often meant that Rundstedt was often treated as a go-between, merely rubberstamping Army Group B’s plans for approval by OKW.

Both Rundstedt and Model agreed that the objective was too ambitious for the troops available and that there was insufficient time to prepare for it. They were concerned that Army Group B would end up in a salient, with its flanks exposed to counterattack.

The Ardennes Offensive had two codenames. The one usually used was Operation Watch on the Rhine (Wacht am Rhein) but an alternative name was the Defensive Battle in the West (Abwehrschlacht im Westen). Both options had been chosen to make them sound like defensive plans.

Rundstedt and Model submitted their alternative plans to OKW during a meeting at Army Group B’s headquarters on 27 October and they had come to the same conclusion, presenting what would be called the Small Solution. Rundstedt’s Plan Martin had Fifth Panzer and Sixth Panzer Armies advancing on a narrow (25-mile-wide) front, north of the line Huy-Antwerp. It avoided the rugged Ardennes terrain and the distance to the Meuse was shorter, while there was good tank country beyond the river. A secondary attack north of Aachen and aimed towards Liège would rip open the Allied line.

Model’s Plan Autumn Fog was broader (40 miles wide), and it covered the north half of Hitler’s front. There would no second attack to the north, and spare troops would follow in a second wave; Seventh Army would also attack later on the south flank. Following the discussion Model amended his plan to match Plan Martin.

Hitler’s directive was delivered to Rundstedt on 2 November and Jodl’s covering letter made it clear who was in charge: ‘The venture for the far-flung objective [Antwerp] is unalterable although, from a strictly technical standpoint, it appears to be disproportionate to our available forces. In our present situation, however, we must not shrink from staking everything on one card.’ Rundstedt replied with his concerns about the shortage of troops and his doubts about the Wehrmacht’s ability to hold on unless the US armies could be destroyed.

Arguments and discussions comparing the Small Solution against the Big Solution followed and while Hitler thought the Small Solution was too small, the generals believed they had insufficient resources for the Big Solution. There would be only one winner; the Führer.

Rundstedt also wanted a simultaneous two-pronged assault, to increase the impact of the offensive. Hitler disagreed and OKW’s operations directive on 10 November forbade one. Although Rundstedt considered making a secondary attack from the Venlo area once the Allies started moving their reserves to the Ardennes, XII SS Corps was too weak to carry it out.

While Hitler’s plans were coming to fruition in November, the Allies intervened with their own offensives and as Third US Army attacked in the Metz sector, First and Ninth US Armies attacked east of Aachen. During the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest it was obvious that divisions were being prevented from withdrawing to refit ready for the Ardennes. Rundstedt and Model believed that success at Aachen promised tactical success and they proposed counterattacking: ‘A surprise attack directed against the weakened enemy, after the conclusion of his unsuccessful breakthrough attempts in the greater Aachen area, offers the greatest chance of success.’ Hitler replied: ‘Preparations for an improvisation will not be made.’

On 26 November Rundstedt and Model were still asking Jodl to change to the Small Solution but Hitler would not budge. Model even took his Panzer Army commanders, Joseph Dietrich of Sixth Panzer Army and Hasso von Manteuffel of Panzer Army, to Berlin to petition the Führer to change his mind on 2 December. He refused again. Four days later Rundstedt and Model submitted a final draft of their operations order detailing a second attack; Hitler again rejected the suggestion. He approved the final version of the operations order for Wacht am Rhein three days later. It was virtually the same plan that the Führer had conceived three months earlier.

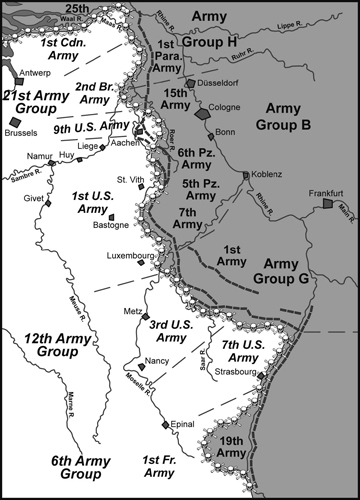

A summary of the situation on the Western Front at the beginning of December 1944. Army Group B had gathered three armies and aimed to cross the River Meuse between Liège and Givet before turning northwest towards Antwerp.