“. . . the sons of God came in unto the daughters of men, and they bare children to them, the same became mighty men which were of old, men of renown.”

Genesis 6:41

A king called Acrisius imprisoned his daughter, Danae, in a tower plated with brass. This tower had only one small window high up in the wall of his daughter’s cell. He committed this terrible crime because a soothsayer had told him that Danae would give birth to a boy who would one day kill him.

But Danae was beautiful and one day Jupiter looked down from the clouds and spotted her. She gladdened his eye and one night he visited her stealthily, coming through the small window in the form of a shower of golden rain.

She gave birth to a boy called Perseus. The king dared not risk killing a son of Jupiter, so he set Danae and the baby adrift on the sea locked in a wooden chest.

Danae loved the boy. She cooed to him in the dark and was glad when he was rocked to sleep by the gentle motion of the waves.

Eventually the chest was washed ashore, to be found by a passing fisherman. He took an axe to it and broke it open. This fisherman was a good man. He took Danae and Perseus in and looked after them, and in time the boy grew big and strong.

Although the fisherman had chosen a simple life far away from the court, he was in fact the brother of the local king, Polydectes. One day Polydectes saw Danae walking by the shore. He wanted her immediately, but she would have nothing to do with him. Perhaps when you’ve made love to a god, no mortal, even a king, is particularly appealing?

The king came up with a plan to get Danae’s protector, Perseus, out of the way. He announced he was holding a banquet. All the young men of his kingdom were commanded to attend and each was to bring the king a horse as a gift. They all did, except for Perseus—the stepson of a simple fisherman having no horse to give. The king rubbed it in and all the other young men laughed in a groveling and lickspittle way. Red with shame, Perseus rashly tried to save face by saying he could bring the king whatever gift he cared to name. He had fallen right into the trap.

“Bring me the head of the Gorgon Medusa!” demanded the king, beaming.

The Gorgon Medusa was one of three monstrous sisters. She was so ugly that anyone who looked at her was instantly turned into stone, and many would-be heroes had died in an attempt to destroy her.

Perseus didn’t know what to do. He was sitting by the seashore, praying for help, when two tall, luminous figures appeared shimmering beside him. He somehow knew they were Athene, the goddess of wisdom, and Mercury, the messenger of the gods. They comforted him and assured him they would protect his mother while he was away. Mercury gave him a flint sickle, sharp enough to decapitate the Gorgon Medusa, and Athene said she would lend him her shield, shiny like a mirror. She advised him to use its reflection to guide the sickle down onto the monster’s neck, so he wouldn’t have to look at her directly.

They told Perseus that he must first go on a long journey to find the Gray Sisters. They would set him on the right path and tell him how to gather the other magical artefacts he would need.

Perseus journeyed north until he found the Gray Sisters in a bleak cave at the foot of a mountain. They looked as if they had been born ancient. They had only one tooth and one eye between them. They were forced to pass these between one another and use them in turn. Perseus crept up on them and snatched the eye as it was being passed between one sister and the next. They were powerless to catch him and he made them swear to give him good advice if he gave them back their eye.

So the Gray Sisters advised Perseus how to find his way to a mysterious country that lay at the back of the North Wind. He followed their instructions and found there wraithlike creatures who could fetch for him the other magical things he would need to complete his mission—the winged Shoes of Swiftness, sandals that would enable him to fly through the sky like Mercury, a magic pouch that could contain the Medusa’s head without being dissolved by its poisons, and the Helmet of Invisibility.

Finally Perseus flew off in search of the Gorgons. Alighting on the ground, he soon found himself walking through a forest of standing stones. After a while he realized that these stones were the petrified forms of people and that the Gorgon Medusa must therefore be nearby.

Then he heard a hissing sound and saw the three monstrous sisters stretched out, asleep and sunning themselves on an expanse of rock. They had green-gold wings the shape of bats’ wings, yellowing tusks, and instead of hair they had a writhing mass of snakes.

Donning the Helmet of Invisibility and using Athene’s shield to guide himself, Perseus crept up on them. Careful not to turn away from the reflection, he sliced the head off the Medusa with one sweep of his flint sickle.

But the snakes on her head did not die with her and their frenzied hissing awoke the other sisters, who came for him. Wearing the Shoes of Swiftness, Perseus leapt into the air and shot off toward the horizon. Drops of blood fell from the pouch, and wherever they fell the land became infested with venomous snakes.

Perseus was longing to see his mother again, but as he neared the island he thought of as home, he changed course. He had seen a beautiful girl with long red hair, chained to the rock by the seashore, naked except for a necklace of emeralds and streams of tears. Now he stopped in midflight to hover around her.

She said her name was Andromeda. She was being sacrificed to a giant sea monster, because her mother had boasted about her beauty . . .

Just then the surface of the sea began to bubble and foam and suddenly a great serpent reared up toward Andromeda.

Perseus shot high in the sky then swooped down to hack at the great neck of the monster again and again until it collapsed into the sea. As the commotion in the water subsided, he cut Andromeda free.2

Perseus and Andromeda arrived at the court of Polydectes. Encircled by the rich young men who had jeered at Perseus, the king still felt brave enough to mock him, refusing to believe that he really had succeeded in his mission. But then Perseus reached down into his pouch and brandished the head of the Gorgon Medusa. As the king and his court drew breath in horror, they were turned instantly into rocks.

The king’s brother gave up fishing to take the throne and married Danae.

Perseus and Andromeda set sail to found a new kingdom, but on the way they chanced upon some games and stopped off for a while. Perseus wanted to take part. Here was a chance to enjoy his prowess. He excelled at all the disciplines, but especially the discus. In fact he threw the discus with such force that it flew out of the performance area of the stadium and into the crowd. When the spectators parted, Perseus saw that the discus was embedded in the head of an old man.

Gemstone carving of young Hercules wearing a lion headdress (from Antique Gems by Rev. C. W. King). Though lions are scarce and hunting them is banned, warriors of the Masai tribes are occasionally cornered and forced to kill a lion in self-defense. Then they will wear its pelt as a headdress in the same way. It’s the mark of a great warrior and attracts a lot of women.

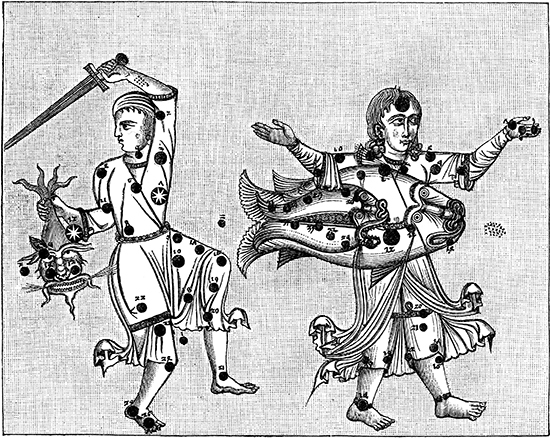

Perseus, the head of Medusa and Andromeda traced among the constellations (from a fourteenth-century Spanish manuscript)

This old man was Acrisius, who had set his daughter Danae and her child afloat in a chest in order to overturn the prophecy that his daughter’s son would one day kill him . . .

* * *

On his travels the king of Athens fell in love for the first time and fathered a son. He was a restless man, an adventurer. He didn’t stay for the birth, but left a pair of sandals and a sword hidden under a great boulder. He told his young lover that when their son was strong enough to lift it and retrieve these possessions, he should seek him out.

So it was that at the age of eighteen Theseus set off for Athens. He arrived to find his father now old and worn out by an unhappy marriage.

His father didn’t recognize him, but as soon as Theseus strode into court, the queen saw in the firm line of his jaw the handsomeness that her husband now retained only in traces. Fearing that Theseus might interfere with her control of the king, she demanded that this young stranger be sent out to bring back the great Cretan bull that was then ravaging the countryside.

Many had died in the attempt, but of course Theseus led the bull back to Athens by the nose. The king decreed it should be sacrificed at a great feast. The queen planned to take the opportunity to poison Theseus, but as the young hero brandished his sword to carve the meat on the bone, the king recognized the sword he had left under a boulder all those years before. Father and son were reunited with much rejoicing. The queen slunk away.

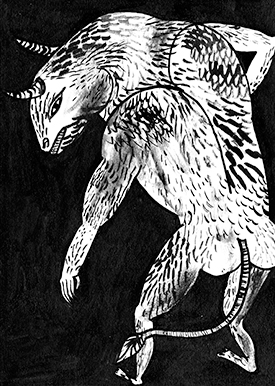

The morning after the night before Theseus was surprised to wake to weeping and wailing in the courtyards of the palace. When he asked what was going on, he was told that this was the day of the year when the Athenians were bound to send a tribute to Minos, king of Crete. Every year seven youths and seven virgins were sacrificed to the Minotaur, a terrifying bull–man hybrid.

Straightaway, Theseus volunteered to be one of the seven. His father pleaded with him not to go. When Theseus insisted, his father made him promise that if he survived the Minotaur he would, before he set sail for home, change the black sails on his ship to white, as a sign to his loving father that he was still alive.

When Theseus arrived on the island of Crete, Ariadne, the king’s daughter, fell in love with the young adventurer. She came to him in the night and told him the secrets of how to defeat the Minotaur, which was kept in a labyrinth. All the previous victims had become lost and disoriented before they were attacked. Ariadne brought Theseus a ball of thread and told him to tie one end to the entrance. Then he should unravel it as he progressed through the passageways, leaving a trail behind him so that he could retrace his steps.

She also told him the secret of how to find your way round a labyrinth, which is to choose the path that seems to take you away from where you want to go.

Theseus followed the path this way and that until at last he penetrated the chamber at the center of the labyrinth. There the Minotaur leapt on him with a great roar. Theseus found the beast’s hide too thick to penetrate with the sword Ariadne had given him. Throwing it aside, he wrestled with the monster until eventually he was able to grab hold of its horns. Then he pulled its great head back and back—until he heard an almighty snap.

Slipping out of the palace before dawn, Theseus and Ariadne ran hand in hand down to the harbor and set sail before her father awoke.

On the voyage back to Athens, they stopped at the island of Naxos.

There the god Dionysus was hidden, watching the beautiful young woman from among the trees that abutted the beach. He waited until she wandered off on her own, then he came to her.

Dionysus was a beautiful, soft-bellied and slightly feminine young man, and he had a sinister air. He offered Ariadne wine, and wooed her with it until she forgot all about Theseus, forgot where she was going and why.

When the time came to leave, Theseus could not find Ariadne. He called for her, but she would not come. So it was that Theseus abandoned Ariadne, as his father had abandoned his mother.

The handsome prince was so distraught he forgot to change his black sails for white ones. His father saw the ship come over the horizon with black sails and, assuming his son had been killed by the monster, threw himself off the cliffs into the sea.

* * *

The stories of Perseus and Theseus both end with the death of the father. In the older story it’s the fulfillment of a prophecy, in the later a cruel accident which is the result of thoughtlessness.

The earlier story is packed with fantastical supernatural elements. As well as prophecy, magical talismans and transformations and the attendance of otherworldly beings, Perseus uses the power of the supernatural to overcome every challenge he faces.

In the story of Theseus, there is only one overtly supernatural element—the existence of the beast itself—and the suggestion is that this monster is kept in its elaborate cage because it is a rarity.

When the demigods slew monsters, they were also slaying the bestial part of themselves and of humanity—because in the mystical view of the world we all share in a spiritual dimension and are connected there, even if we appear separated into different bodies in the physical world. Humanity had been given animal consciousness, but that gift carried with it a danger for every human being—the danger of turning bestial and monstrous.

A darker, colder age was dawning. The lives of all Earth-dwellers were becoming harder. If bodies had once been densified imaginations, more like phantoms than flesh and blood, gravity was now weighing them down as bones were thickened and became more rigid. Humans dragged themselves more slowly over the surface of the Earth. They lived in a bloody, death-drenched world, a world gone wrong.

And in an ironic twist of fate they discovered that as they were less and less able to depend on the gods, the gods in some strange way turned out to depend on them . . .