21

Socrates and His Daemon

The Emperor asked a sage to be brought to court. “What is the highest truth?” he wanted to know.

“Total emptiness . . . with no trace of holiness,” said the sage.

“If there is no holiness, then who, where or what are you?”

“I don’t know,” the sage replied.

Question everything. Test it with reason. Look at the assumptions behind it, take those assumptions apart and question your questions too. Awareness of ignorance is the beginning of wisdom.

* * *

In the West, this way of thinking started with Socrates. It is because of him that we place such a high value on knowing. Socrates is the father of Western academic philosophy—and also, as we shall see, intellectual integrity.1 Yet he had his own personal daemon, an uncanny adviser who had supernatural knowledge of the world, who often knew better than him and who repeatedly whispered in his ear, telling him what he should do. “It began in my early childhood,” he said, “a sort of voice which comes to me.”

Socrates was born around 470–469, in the golden age of Athens, the time of its great flowering in the arts and sciences. He was the son of a poor sculptor and a midwife.

There is a story that one day the young Socrates was trying to carve a statue of Apollo’s daughters, the Three Graces. Frustrated, he threw down his chisel, saying he would rather carve his own soul.

He was spotted by a wealthy man, who paid for his education.

In his twenties, while the finishing touches were being applied to the Parthenon, Socrates was talking with the great thinkers of the day. As a soldier, he also fought for Athens with great courage, and he was a hero, too, at drinking strong drink. He was physically strong, but ugly with a flat nose. His face looked like the face on statues of the centaur Chiron, people said.

But what really distinguished him were the voices—the voice of his own private daemon and his own voice, questioning everything.

As he reached middle age, he was still poor. He went around barefoot in a dirty old cloak. He could have been earning a living as a teacher, but he had always refused to take money for his teaching. It was also said that at the market he didn’t concern himself with how much things cost or how he was going to find the money to pay for them, but with listing all the things he didn’t need or want. “I contend that to need nothing is divine,” he said, “and that the less a man needs, the nearer he approaches divinity.”

Be that as it may, as his wife might have said, he wasn’t a good provider for his family. His wife used to nag him. On one occasion her anger and frustration exploded and she emptied a chamber pot over his head.

The Athenians seemed to regard him as what we today might call “a bit of a character.”

His daemonic voice was internal. No one else could hear it. It would come to him unbidden.

Early one morning while on a military campaign Socrates fell deep into thought in the middle of the camp. He just stood there. People were astonished to see him still standing in the same place at midday and then that night soldiers pulled their beds out of their tents so they could watch him. Only in the morning of the next day did he come to, appear to say a prayer to Apollo and walk away. Then, it seemed, his voice warned him not to attempt to cross a particular river until he had performed a rite of atonement.

His daemon evidently foresaw the future. On another occasion he was walking with friends through the city streets, when he suddenly stopped because his daemon told him not to take a particular route. His friends, who would not be advised by him, did take that route—and found themselves run over by a herd of pigs.

Silenus and a panther, from an antique gem, probably Roman (from Antique Gems by the Rev. C. W. King, 1866). There is a tradition that Socrates was a reincarnation of the satyr Silenus, which is reflected in the statues of them, which have the same face. It’s hard not to see the influence of the daemon of Socrates on the account of daemons in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy.

His daemon also advised about bigger things. During the battle of Delium it advised Socrates to take a particular route that enabled him to rescue Alcibiades and two other famous Athenians. The comrades who declined to follow this advice were overtaken by the enemy and killed.

During the Peloponnesian War, Socrates was also told that Athens should not send out a particular expedition. Yet again his advice wasn’t heeded and the expedition duly turned out to be disastrous.

* * *

Why was Socrates privileged in this way? Why did this voice come to him? According to his pupil Plato, we are all given a daemon at birth to guide us through our earthly lives. According to the historian Plutarch, we are all able in principle to hear its divine promptings, but Socrates could hear them more clearly than most people because he was not as distracted as most of us are by the passions that enflame bodily nature and cloud the mind.

Someone went to consult the oracle at Delphi, asking if there was anyone alive wiser than Socrates.

The priestess simply said, “No.”

When he found out about it, Socrates questioned what the oracle had said. He wanted to know the exact words.

“How can I be the wisest man in the world?” he said. “I know nothing!”

He knew that the pronouncements of the gods—in this case Apollo—were never straightforward, often enigmatic, ambiguous and open to misinterpretation. In his view these pronouncements demanded thinking and questioning.

Later Socrates decided that Apollo had given him a divine mission to question everything. He thought it was good to know. He believed that if anyone faced with a choice knew which was the better course of action, knew all the implications and knew all the good that would result from choosing it, then that person would naturally feel unable to choose the worse course of action. For Socrates, then, knowledge was virtue.

He wanted to try to work out how we should live. Happiness, he argued, did not come from wealth or power or other external things, but from knowing what was good for you, for your soul. The oracle at Delphi advised, “Know thyself,” and Socrates tried to work out in reasonable, logical terms what that meant.

In the person of Socrates the human intellect was beginning to find out what it might be capable of—to flex its muscles. Socrates would rush about the city talking to everyone, not just the statesmen, generals and philosophers, but the tradespeople, shopkeepers and courtesans. Just as Gilgamesh had rushed around trying to find someone strong enough to give him a good fight, so Socrates looked for someone who could match his intellectual strength.

And so he tested everyone. He would draw people’s opinions out of them, unravel the assumptions behind these opinions, then look for contradictions and try to reduce them to absurdity. He could be charming, funny and fascinating, but sometimes he was also teasing and sarcastic. Perhaps he didn’t know his own strength? Where he found ignorance, he mocked it, and he sometimes teased people in a way that made bystanders laugh.

“Philosophy,” he said, “is the greatest kind of music.” His philosophy—his powers of reasoning—often had a strange effect on people. It charmed them—but not always in a pleasurable way. Sometimes people engaged in conversation with Socrates found they no longer knew what they knew or believed, sometimes so much so that they went into shock—as someone said, as if they’d been stung by a stingray. Of course they weren’t used to being tied up by logical argument.

A friend told Socrates that he was wise not to travel, saying that if he behaved abroad as he did in Athens, he’d be arrested as a wizard. Of course, being a wizard, the friend reminded him, was often punishable by death.

The comment was prophetic. Socrates was making enemies. Not everyone found him amusing. A group of young men had gathered around him and some of the Athenian elite found this sinister. Was he subverting them? Also, if Socrates said that he knew nothing, what did that say about the great and powerful men he so easily trounced in public debate? Not everyone appreciated being made to look stupid.

We saw that by the time of the prophets, the political leaders of the Jews were no longer their great spiritual leaders. Socrates and his young follower Plato believed that political leaders should still be “the ones who know” or, as Plato would put it, “philosopher kings.” Socrates mocked Athenian ideas of democracy, calling it an amusing entertainment, and he also mocked politicians for partying with chorus girls.

Athens had been losing some of its self-confidence. It had suffered defeats in the Peloponnesian War and behaved in an unjust and cruel way to some of its enemies. Some people felt uneasy, and perhaps thought that all Athenians should pull together. It wasn’t a good time to be “off message.”

Socrates was summoned before two officials who told him of a new law by which he would be forbidden to use his questioning, reasoning methods to influence the youth of the city.

“Can I ask you a question—just to make sure I understand your orders?” he said.

“You may.”

“Of course I want to obey the law—but are you telling me that I am forbidden from teaching the young in a reasonable way? Is the implication that . . .”

“Because you are a fool, Socrates,” said the official, angrily, “I will put it in plain language that even you can understand: you are forbidden to talk to the youth of Athens in any way whatever.”

Socrates had two particular enemies who became his leading accusers: a poet he had humiliated in a public debate and a rich merchant who did not like the influence Socrates had on his son. He was brought to trial before 500 judges and accused of corrupting the youth of Athens and not believing in the gods of Athens—believing instead in his own private daemon.

Asked why he taught the young and did not take part in debates in the great public assemblies, Socrates said—in what must have seemed to the assembled leaders and officials to be a calculated insult—that his daemon had advised him not to take part in politics because it would stain his soul and make him less able to see the truth. “Surely you don’t want to punish me for telling the truth?” he said.

According to Socrates, a philosopher should not dwell on the petty, transient affairs of men, but fix his attention instead on the eternal realities to be seen in the patterns that the stars and planets make in the sky. He was here referring to the work of the great spirits of the stars and planets in forming the world and directing it.

Socrates was questioned on the report that the oracle of Delphi had said he was the wisest man on Earth. He suggested that Apollo might have been joking, and the assembly roared its disapproval.

It did likewise when Socrates was questioned about his daemon. He said it was important to note that the daemon never made him do anything. A daemon seeks to take you over and use you, but Socrates’s daemon left it up to him to decide what to do.2

As his trial continued, Socrates referred to many instances when his daemon had accurately predicted the future. But everything he said seemed to speak to his judges of his arrogance.

When asked if he had prepared a defense, he said he laid his whole life before the judges. He said that he had always spoken for truth and justice—and that that should be his defense.

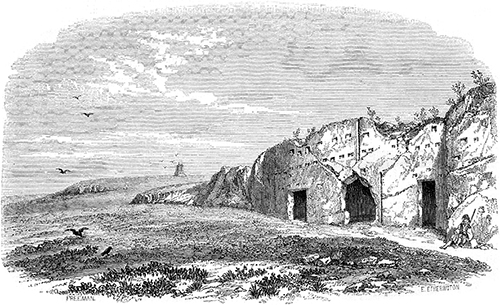

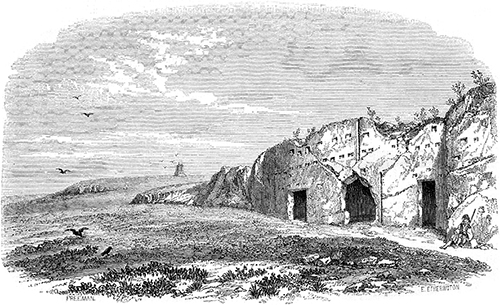

The prison where Socrates was held (engraving by a nineteenth-century traveler)

Later he was asked why he had not used his usual eloquence to sway the judges, and he said that his daemon had told him not to. He continued: “I have been told that if I am caught questioning the young and philosophizing, I shall die. I should say to you, men of Athens, that I reverence you and love you, but as long as I breathe and am able, I shall not cease to philosophize. I am about to say something at which perhaps you will cry out, but I pray you not to do so. For you know well that if you should kill me, you would not hurt me as much as you would hurt yourselves.”

He was found guilty.

When asked if he would like to suggest a sentence, he proposed that either they gave him the highest honor that they could bestow or fine him the smallest coin there was. He seemed not to take his accusers seriously, even under threat of death.

A second vote was taken and he was condemned to die.

He said calmly, “There has befallen me that which men may think and most men do account to be the greatest of evils.” And yet, he went on, his daemon had given him that morning no sign, either at home or here in the court, that by being condemned to death he had been overtaken by any evil.

“What has happened to me seems to me to be a good thing, and if we think death to be an evil, we are making an error, so be of good hope, my judges. Know too that I am in no way angry with those who have accused or condemned me, though they have condemned and accused me with no good will but rather with the intention of hurting me. Life after death will surely be a place where they don’t condemn a man to death just for asking questions.”

He was condemned to drink hemlock, and the sentence was to be carried out in a month’s time.

Friends urged him to escape, but he refused to do so.

On the appointed day he said, “Soon I must drink the poison, and I think I’d better take a bath first, so the women won’t have the trouble of washing my body after I am dead.”

He briefly saw his wife and three sons. His wife was crying, but he sent them all briskly away.

When the time arrived, his executioner, too, burst into tears. Socrates told him: “I return your good wishes and will do as you bid.”

As he raised the cup to his lips and drank, quite cheerfully, his followers were weeping. He rebuked them, saying that he had been told that a man should die in peace.

His legs began to fail and he lay down. “When the poison reaches my heart, that will be the end.”

He covered his face up. Then after a while a movement was heard and they uncovered his face to find that his eyes were set.

Socrates had finished carving his soul. He had tried to teach how to live; now he tried to teach how to die.

Because our age is so soused in materialism, we may find it hard not to wonder if Socrates really did want to die. It occurs to us to doubt his sincerity. But the fact of the matter was that at that time almost everyone believed in a spiritual reality. For Socrates the body was “the tomb of the spirit.” The spirit had fallen into matter, which had gradually hardened around it, but in between earthly lives the spirit was free to ascend to higher, spiritual realities.

It has been suggested that Socrates was executed for introducing a new god or gods in the shape of his own daemon. But Athens was a thriving marketplace for new ideas, new beliefs, new gods. It prided itself on open discussion of these matters and tolerance of a huge range of different gods. No, what offended the Athenians, what was unacceptable, was that this new god—Socrates’s daemon—was private to himself and internal. Only a few hundred years earlier the gods of Homer and the God and angels of Moses had acted, as we have seen, in huge public events witnessed by thousands. They were awesome powers active in the world. In the story of Socrates, as with Elijah and the Buddha, we see that a new arena for divine intervention was opening up.3

Socrates was a martyr. He died for the inner life.

* * *

Plato was twenty-five when Socrates died.

The works of Plato give us the first systematic account of idealism. Idealism, as we have seen, is the belief that mind came before matter, that matter comes from mind and is dependent on it, and that mind is in some way more real than matter. It had never been written down as a philosophical system before Plato, but up until that point pretty much everyone in history had believed in it without question.

Because we are most likely today to encounter idealism as dry academic theory, usually as a theory of knowledge, it is easy for us to forget that for most of history it has been a philosophy of life. People experienced the world in a way that accorded with it. They experienced the physical world responding to their mental acts, in prayers for example. They had religious, spiritual, mystical experiences, and saw the world working according to patterns that just wouldn’t be there if the world were only a place of atoms knocking against atoms.

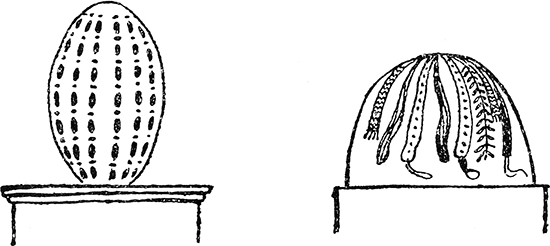

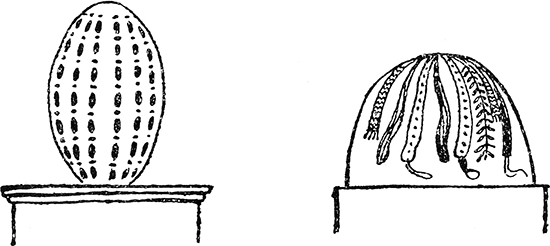

The omphalos (from Architecture, Mysticism and Myth by W. R. Lethaby, 1891). In Greek thought Apollo was the Logos or Word, the source of the world’s harmony, weaving in eternal song all that is and will be. The most sacred thing at Delphi was the omphalos stone that marked the sacred center of the world and the place where all worlds met. This stone was covered by a net, mathematically generated by the numbers of the gods’ names. This net depicted the world’s soul. It caught the thoughts or ideas of the great Cosmic Mind and pulled them into the material world. We each have a sacred center like this in our body.