This twofold immersion in the fathomless depths of the divinity.

Angela of Foligno, The Book of Visions and Instructions

To make foundations, to constitute, to write a constitution: but how? In the event, your reform of the Carmelite order would rest on two pillars: constitution and fictions. On one side, the strict regulation and jurisdiction whose great purpose was to guarantee the right conditions for the outside-time of contemplation in worldly time. On the other, the “account” or narrative of inner experience, linking the journey toward the infinity of the Other with the humdrum trials of dealing with the passions of women and the history of men.

On completing the Constitutions by writing (yes, that again!),1 The Way of Perfection,2 then the Foundations,3 you imbued your sequestered sisters—whom your tongue often did not spare—with a psychic and indeed political life that was utterly without precedent, not only in the religious world but in any community of women, and perhaps of men, at that time. The story of your interior experience, resonating with the experience of your sisters and the other protagonists of the foundations, helped to literally unlock these cloistered souls. The narrative tenor of your writing (labeled “account” or “fiction”), which falls outside “genre” by mixing them all, appeals to the freedom of the spirit with an audacity, humanity, and distinct mastery of the moderns that contrast with the searingly rigorous texts of Ignatius Loyola, your senior by twenty years,4 as much as with the skepticism of the Essays of Michel de Montaigne, your junior.5 And it’s precisely this theological and philosophical “ignorance,” this “unlettered” freshness that would turn The Way of Perfection and the Foundations into a breviary and a chronicle at once, mingling sensual delicacy and pragmatic intrepidity in a thought whose universal historic range and scope have still not been fully fathomed.

Just now, however, in 1566, you are contemplating the idea of constituting with María de Jesús Yepes, drawing on her knowledge and borrowing from her experience. It is to all appearances a bid to bring the Carmelites back to stricter standards. Is this to combat the laxity and drift of the Mitigated Rule and the whole epoch itself? To stand up more effectively to Lutheran rigor? Your implacable severity signals a far grander ambition, Teresa, my love, than any feebly moralistic design: you are intent upon inscribing into the accelerating time of history the outside-time of your understanding with the Other. Enclosure, poverty, and austerity are but three ways to convey the love of war and to acknowledge the war on love.

So now, along with María de Jesús Yepes, do you seek to return to the Primitive, ascetic Rule, the way she observed it at the Carmelite convent in Mantua where the nuns are, it is said, “walled up”? In a way; but it is rather more a matter of returning to that point in order to rethink, to recommence anew. “Constitution,” for you, will contribute to inaugurating that other time that inhabits you already, the one I have read and seen taking shape in you.

The cornerstone will be enclosure, a shield against the levities and licenses you observed at the Incarnation, which it is high time were abolished, now that France has fallen prey to calamity, thanks to the “havoc” wrought by that sect of “miserable” Lutherans, as you put it.6 María de Jesús wants to add on another cornerstone that is just as necessary for embarking on the way of perfection: absolute poverty.

“Until I had spoken to her, it hadn’t been brought to my attention that our rule—before it was mitigated—ordered that we own nothing.” This was something that “I, after having read over our constitutions so often, didn’t know.”7 A descendant of wealthy merchants like you, Teresa, can’t do less than begin to “constitute” by renouncing, firmly and finally, the chattels of this world! Before, “my intention had been that we have no worries about our needs; I hadn’t considered the many cares ownership of property brings with it.” So far so natural, and so Christlike. To cap it all, María nudges you toward the third principle of your reform: the discalced nuns are to live from their labor alone, and forgo all private income and allowances. Nothing but alms and personal effort!

Saying Mass, preaching, teaching, even tending the sick—these are tasks for men; your “daughters” will be encouraged to spin at the wheel, weave, sew, embroider. As a purist, you ban the more elaborate forms of needlework. Spinning and weaving are fine, but beware of lacy fripperies, guipures, and tapestries, for too much sophistication (labor curiosa) leads minds to stray from God! And no working with gold or silver, that’s forbidden above all.

Between the Carmelite provincial, Ángel de Salazar, who disapproved of such austere, impoverished convents; Bishop Álvaro de Mendoza, who took you under his wing; the Dominican Domingo Báñez, who supported you; and the Franciscan Pedro de Alcántara, who inspired you, slowly but surely you drew up the future constitution. In 1567, with the approval of the Carmelite general, the Italian-born Juan Bautista Rubeo, the new rules were written out with the assistance of María de Jesús, before she went off to found the Imagen convent at Alcalá de Henares. The text was then passed on to John of the Cross for him to use as a template for the discalced male regime. As the original has been lost, the only version we have has been reconstituted from the Alcalá copy and the rules for the Carmelite friars. To my mind, this short text (twelve sixteen-page chapters, of which you authored only the first six), regulating solitude within group life by dint of a wise balance of asceticism and tenderness, is the very condensation of your art of founding time.

After all, can anything be regulated without regulating time? How to make best use of time has always been a concern for monastic orders. Hence chapter 1, rule 1:

Matins are to be said after nine, not before, but not so long after nine that the nuns would be unable, when finished, to remain for a quarter of an hour examining their consciences as to how they have spent the day. The bell should be rung for this examen, and the one designated by the Mother prioress should read a short passage from some book in the vernacular on the mystery that will serve as a subject for reflection the following day. The time spent in these exercises should be so arranged that at eleven o’clock the bell may be rung to signal the hour for retirement and sleep. The nuns should spend this time of examen and prayer together in the choir. Once the Office has begun, no Sister should leave the choir without permission.8

Matins at nine, “examen” for fifteen minutes with meditation in Spanish upon a particular mystery, all “together in the choir.” Alone and together, meditation and work; the hours of the day are planned in such a way that time does not elapse but stands up straight, vertical, the frozen present of the contemplation of the Other. There are no distractions: your authorization of the vernacular tongue is not a license, it merely helps familiarize each nun with her Spouse and assimilate Him to whatever is most “her own,” both infantile and maternal. Likewise with chanting: to forestall possible backsliding, you prohibit the seductive runs of Gregorian notation, stipulating “a monotone and with uniform voices.” As for the rest of the rite, even Mass will be “recited,” to save time, “so that the Sisters may earn their livelihood.”9

Thus set up, the absolute present of contemplation will be paced according to the rhythms of the seasons and the movement of the sun. The bell rings out the calls to prayer, morning, noon, and night, and organizes the space of solitude with others: indoors or out, chapel or cell, garden or kitchen. The hours of the divine office (matins, prime, terce, sext, none, vespers, compline, lauds) and the milestones of the Catholic calendar (Christmas, Lent, Easter, saints’ days) divert the quantitative flow of “passing time” into the outside-time of contemplative suspension.

The reform of time imposed by your Constitutions, Teresa, does not create a new calendar. Obviously not, since you are consciously aware of not founding a new religion. To take refuge in Catholic time as it exists (your Spouse’s calendar, the holy feasts and liturgies) enables you to better hollow out this time in which you recognize yourself, and of which you demand that it recognize you—the better to shoot it like an arrow deep inside toward the amorous intensity, carried to extremes, that will help you to detach from the world in order to cleave to the Other until “participating” in Him. Recognition and exile: never one without the other. Your genius lies in this paradox, which conformists (traditionalist and modernist alike) refused to accept, and could only be admitted by bolder dialectical minds in the wake of the Council of Trent.

This headlong rush into the worlds of business, diplomacy, funding, this accumulation of ruses, affinities, seductions, and humiliations—what were they for? To hollow out places beyond place, enclosures harboring an outside-time, protecting the Infinite. The discalced universe founded by your Constitutions is your last oedipal assault, a cold disavowal of the world of families, wealth, secular honor. Could it be in veiled resonance with the secrets of the Marranos disclaimed by your father and uncle, though they “participated” in them? Silent prayer welded a secret world inside you, which the Carmelite reform will institutionalize. In that world, the parents’ world, you make a kingdom that is not of this world. At the gate of the discalced houses you leave the Cepeda y Ahumadas and everything to do with them behind. Because from now on, you’re plain Teresa of Jesus.

Taking your vows thirty-five years ago at the Incarnation, with the secret complicity of Uncle Pedro and the support of your readings of Osuna, had not been, after all, enough of a break with the order of families, of family, the law of management-gestation-generation. From now on, there’s no ambiguity: at the cost of the sadomasochism that your joyous lucidity ceaselessly modulates into willpower or serenity, you are free. But at what a cost! It’s another paradox, my baroque Teresa, and it won’t be the last.

Before throwing yourself into the race that will keep you busy for the next fifteen years, the time of Infinity thus negotiated with ephemeral, worldly time nudges you to etch a thousand meticulous details into your regulations. The most essential are as follows.

Enclosure, you say That means solitude, silence, and detachment from the world.

No nun should be seen with her face unveiled unless she is with her father, mother, brothers, or sisters, or has some reason that would make it seem as appropriate as in the cases mentioned. And her dealings should be with persons who are an edification and help for the life of prayer and who provide spiritual consolation rather than recreation. Another nun should always be present unless one is dealing with conscience matters. The prioress must keep the key to both the parlor and the main entrance. When the doctor, barber-surgeon, confessor, or other necessary persons enter the enclosure, they should always be accompanied by two nuns. When some sick nun goes to confession, another nun must always be standing there at a distance so that she sees the confessor. She should not speak to him, unless a word or two, only the sick nun may do so.10

Outside-time in time demands total dispossession from the outset: nothing for oneself. The sisters cannot own anything, not even a book:

In no way should the Sisters have any particular possessions, nor should such permission be granted; nothing in the line of food or clothing; nor should they have any coffer or small chest, or box, or cupboard, unless someone have an office in the community. But everything must be held in common.…the prioress should be very careful. If she sees that a Sister is attached to anything, be it a book, or a cell, or anything else, she should take it from her.11

You who were once such a stylish young thing, you now bear down on every sign of caring about appearance or comfort. Attire will be austere, with rope-soled sandals made of hemp, habits of coarse cloth or rough brown wool, hair chopped short under the wimple; no colors, no mirrors, Spartan cells, and straw pallets.

A fast is observed from the feast of the Exaltation of the Cross, which is in September, until Easter, with the exception of Sundays. Meat must never be eaten unless out of necessity, as the rule prescribes.

The habit should be made of coarse cloth or black, rough wool, and only as much wool is necessary should be used.…Straw-filled sacks will be used for mattresses, for it has been shown that these can be tolerated even by persons with weak health.…Colored clothing or bedding must never be used, not even something as small as a ribbon. Sheepskins should never be worn. If someone is sick, she may wear an extra garment made of the same rough wool as the habit.

The Sisters must keep their hair cut so as not to have to waste time in combing it. Never should a mirror be used or any adornments; there should be complete self-forgetfulness.12

For those who haven’t grasped that this detachment is the imperative condition for belonging to the Other, The Way of Perfection sets out, in greater psychological detail, the implications of your juridical-constitutional rigor:

I am astonished by the harm that is caused from dealing with relatives. I don’t think anyone will believe it except the one who has experienced it for himself. And how this practice of perfection seems to be forgotten nowadays in religious orders! I don’t know what it is in the world that we renounce when we say that we give up everything for God, if we do not give up the main thing, namely, our relatives.13

Once nature, that is, “the relatives,” has been dealt with, there naturally follows the need to guard against any special affection between sisters. Teresa is careful to put bounds on female passions, veritable poisons that she compares to the tumultuous feelings between siblings and to a “pestilence”:

All must be friends, all must be loved, all must be held dear, all must be helped. Watch out for these friendships, for love of the Lord, however holy they may be; even among brothers they can be poisonous. I see no benefit in them. And if the friends are relatives, the situation is much worse—it’s a pestilence!14

Let no Sister embrace another or touch her on the face or hands. The Sisters should not have particular friendships but should include all in their love for one another, as Christ often commanded His disciples. Since they are so few, this will be easy to do. They should strive to imitate their Spouse who gave His life for us. This love for one another that includes all and singles out no one in particular is very important.15

The inevitable pleasures between sisters (female homosexuality is endogenous!) must be closely watched out for, then. Beware elective affinities! Transform them into “general” bonds, into the cement holding the group together! Is that your message? Sooner said than done!

With rather more finesse, your Motherhood—sensual and prudent—softens these rigors by drawing attention to another, more delightful Cross that afflicts those who care for others, and know them down to “the tiniest speck [las motitas]”: “On the one hand [these lovers] go about forgetful of the whole world, taking no account of whether others serve God or not, but only keeping account of themselves; on the other hand, with their friends, they have no power to do this, nor is anything covered over; they see the tiniest speck. I say that they bear a truly heavy cross.”16

When, in situations of mystical ascesis and the acquisition of this insight into human relationships, penances seem called for, you are careful to qualify them: “Should the Lord give a Sister the desire to perform a mortification, she should ask permission. This good, devotional practice should not be lost, for some benefits are drawn from it. Let it be done quickly so as not to interfere with the reading. Outside the time of dinner and supper, no Sister should eat or drink without permission.”17

Moments of relaxation—an innovation of yours—will be allowed:

When they are through with the meal, the Mother prioress may dispense from the silence so that all may converse together on whatever topic pleases them most, as long as it is not one that is inappropriate for a good religious. And they should all have their distaffs with them there.

Games should in no way be permitted, for the Lord will give to one the grace to entertain the others. In this way, the time will be well spent. They should strive not to be offensive to one another, but their words and jests must be discreet. When this hour of being together is over, they may in summer sleep for an hour; and whoever might not wish to sleep should observe silence.18

It goes without saying that delicacies are forbidden: the menu is meager, and fasting lasts for six months. The Constitution for Saint Joseph’s bans meat, save in cases of absolute necessity, as we have seen, but it does allow for fish and eggs, as well as unlimited bread and vegetables. Positively mouthwatering! Lest we forget, there’s nothing like frugality to condition the detachment from self that solitude is expected to foster.

Good spiritual nourishment, equally under surveillance, will feed the souls whose stomachs have thus been purified:

The prioress should see to it that good books are available, especially the Life of Christ by the Carthusian [Ludolf of Saxony], the Flos Sanctorum [a collection of lives of the saints, including the Golden Legend by Jacobus de Voragine], the Imitation of Christ [Thomas à Kempis], the Oratory of Religious [Antonio Guevara], and those books written by Fray Luis de Granada [the Book of Prayer and Meditation, the Sinners’ Guide] and by Father Fray Pedro de Alcántara. This sustenance for the soul is in some way as necessary as is food for the body. All of that time not taken up with community life and duties should be spent by each Sister in the cell or hermitage designated by the prioress; in sum, in a place where she can be recollected and, on those days that are not feast days, occupied in doing some work. By withdrawing into solitude in this way, we fulfill what the rule commands: that each one should be alone. No Sister, under pain of a grave fault, may enter the cell of another without the prioress’s permission. Let there never be a common workroom.19

I see that the list of books authorized by the prioress is short but edifying, and the cleverest of the discalced nuns would be able to commit their salient passages to memory, so as to form part of a duly indoctrinated, elite corps.

I also note that this austerity wisely applies to one and all, fomenting a kind of equality between the sisters that even includes the mother superior:

The Mother prioress should be first on the list for sweeping so that she might give a good example to all. She should pay careful attention to whether those in charge of the clothes and the food provide charitably for the Sisters in what is needed for subsistence and in everything else. Those having these offices should do no more for the prioress and the older nuns than they do for all the rest, as the rule prescribes, but be attentive to needs and age, and more so to needs, for sometimes those who are older have fewer needs. Since this is a general rule, it merits careful consideration, for it applies in many things.20

Over the years, the various foundations would show that it was better to establish the prioress’s authority from the start and enshrine total respect for the hierarchy; for the moment, however, Teresa refers to herself as an “older sister.” Such were the optimistic beginnings of an institution that dreamed of equality. When at length she realized that the human animal, even behind the bars of a cloister, requires steering by an unambiguously firm hand, La Madre would duly take this into account.

But this is still only the start of an unimaginable adventure. The goal was no more or less than to found, in this world, the interiority of an absolute love beyond the reach or ken of this world; to noise abroad the work of this love by isolating it, rendering it invisible and indeed untouchable, and by the same token infinitely desirable. Nothing could have gone more against the grain at this time, the apogee of the Renaissance, as colonization was spreading and industry beginning to develop. But the repercussions of the Council of Trent subsumed this Teresian casuistry into the cultural revolution that was the Counter-Reformation, without anyone knowing where exactly this would lead: to the impasse of an archaism in whose swamp of supernatural manifestations Renaissance or Protestant progress would find itself mired? Or to the awakening of unsuspected energies and fruitful singularities, as enigmatic and confounding today as they ever were?

In The Way of Perfection, the three points that summarize the Constitutions allude to a Paradise located at the intersection of the “inward” and the “outward”:

I shall enlarge on only three things, which are from our own constitutions, for it is very important that we understand how much the practice of these three things helps us to possess inwardly and outwardly the peace our Lord recommended so highly to us. The first of these is love for one another; the second is detachment from all created things; the third is true humility, which, even though I speak of it last, is the main practice and embraces all the others.21

The fundament is love according to prayer: in these days of religious war, you must pray (inwardly) and make it known by taking up as much space as possible (outwardly). Recollect yourself at the very heart of your interior castle, but swarm through the mountains and valleys. In a Carmel harking back to the old ways, contemplation amounts to a warrior kind of love. Are some “unfortunate heretics” attacking the Catholic fortress in which La Madre desires to house her reform? To arms, to war! But one cannot gallop into battle without first outlining the Paradise of love; without exploring in every direction love’s exaltations, which only thus, accepted at last, open up into Nothingness.

Let us return now to the love that it is good for us to have, that which I say is purely spiritual. I don’t know if I know what I am saying.…For I don’t think I know which love is spiritual, or when sensual love is mixed with spiritual love, nor do I know why I want to speak of this spiritual love.…The persons the Lord brings to this state are generous souls, majestic souls. They are not content with loving something as wretched as these bodies, however beautiful they may be, however attractive.... And, in fact, I think at times that if love does not come from those persons who can help us gain the blessings of the perfect, there would be great blindness in this desire to be loved. Now, note well that when we desire love from some person, there is always a kind of seeking our own benefit or satisfaction…

It will seem to you that such persons do not love or know anyone but God. I say, yes they do love, with a much greater and more genuine love, and with passion, and with a more beneficial love: in short, it is love. And these souls are more inclined to give than to receive. Even with respect to the Creator Himself they want to give more than to receive. I say that this attitude is what merits the name “love,” for these other base attachments have usurped the name “love.”22

Who said enclosure? Inwardly and outwardly, you constitute whatever is necessary to harbor love, to set it ablaze with ecstasy, indifference, endurance. You are ready, Teresa, to confront the world from the vantage point of that nonworld. Comfort does not sit well with prayer, ecstasy is not a pampered but a painful act, incompatible with easy living: “regalo y oración no se compadece.”23

Are you, like Angela of Foligno, perpetually engaged in a “twofold immersion in the fathomless depths of the divinity”? Not really. What you do instead is to walk it, explore it, elucidate it. The idea is to create the optimum conditions for attaining, through recollection, the intimate secrecy, the “closet” (Matt. 6:6) of prayer, the prayer “all night” (Luke 6:12) engaged in by Jesus himself, for “it has already been mentioned that one cannot speak simultaneously to God and to the world.”24 Time to withdraw from the world, then, to step back from its “frenzy”; but also from “bad humors” or melancholia, on “days of great tempests in His servants.”25 To stand never so far from the Master “that He has to shout,” close enough for the person at prayer to “center the mind on the one to whom the words are addressed.”26 This pact with the Other should neither be a fusion, nor an obstacle to comprehension: “It will be an act of love to understand who this Father of ours is and who the Master is who taught us this prayer.”27

And yet, with no striving on the part of the spirit, a transfer of intimacies is what occurs, an outpouring of pleasure between communicating vessels. The “divine food” of happiness, then,28 the understanding of the “nothingness of all things,” which together transmute the “pain” into “joy.” Let “reason” itself “raise the banner”!29 The “interior” of every person will thus find itself appeased: “If the soul suffers dryness, agitation and worry, these are taken away.”30 In a word, the soul is returned to bliss. “The delight is in the interior of the will, for the other consolations of life, it seems to me, are enjoyed in the exterior of the will, as in the outer bark, we might say.”31

Severed from this “exterior life,” the cloistered soul—which Teresa reveals and instructs in the Way—will not allow itself to be held back by any obstacle. Of course, La Madre laments those “scattered” souls who behave like “wild horses…always restless,”32 and this remonstration could just as well apply to herself. However, the enclosure of Heaven, irrigated by the Other’s water or milk, is not impervious to the “active,” “powerful” fire, “not subject to the elements,” whose inability to extinguish its opposite, water, “makes the fire increase!” Far from being passive, the soul Teresa summons up in her writing is a blaze of love, tantamount for La Madre to the fire of “liberty”: “No wonder the saints, with the help of God, were able to do with the elements whatever they wanted.”33 The “poor nun of St. Joseph’s” licenses herself to wage war in order to “attain dominion over all the earth and the elements.”34 War against herself, by practicing “interior mortification”;35 war to “conquer the enemy,” meaning the body first of all. Once souls have become “lords of our bodies,”36 they wage war against the last enemies, among whom must be counted those “learned men,” who “all lived a good life—incomparably better than I,”37 but who have not been blessed with true “consolations [pleasures, refreshment: gustos] from God.”38 Or against what she calls the “night owls” or “cicadas,” those Carmelites of the observance who haven’t gone along with Teresa’s reforms.39

Thus inflamed, the soul on its path to perfection never encounters a “closed door,” for its state of “suspension”40 makes an invincible combatant of it. Cloistered but not tied down, its deep refreshment in itself, at once water and fire, compels it to brave the antagonism of those who are content with the “exterior life,” the “outer bark”:

I had no one with whom to speak. They were all against me; some, it seemed, made fun of me when I spoke of the matter, as though I were inventing it; others advised my confessor to be careful of me; others said that my experience was clearly from the devil. My confessor alone (even though he agreed with them in order to test me, as I came to know afterward) always consoled me.41

Not even devils can scare you anymore, Teresa. Fortified by your union with the Beloved, you ignore them, like so many pesky flies! “For although I sometimes saw them, as I shall relate afterward, I no longer had hardly any fear of them; rather it seemed they were afraid of me. I was left with a mastery over them truly given by the Lord of all; I pay no more attention to them than to flies.”42

Contemplative and secluded as you are, you harbor a military vision of the world, my dear Teresa; the Parisian Psychoanalytical Society crowd would call it paranoid, and they wouldn’t be completely wrong. Witness this vision:

I saw myself standing alone in prayer in a large field; surrounding me were many different types of people. All of them I think held weapons in their hands so as to harm me: some held spears; others, swords; others daggers; and others, very long rapiers. In sum, I couldn’t escape on any side without putting myself in danger of death; I was alone without finding a person to take my part. While my spirit was in this affliction, not knowing what to do, I lifted my eyes to heaven and saw Christ, not in heaven but quite far above me in the sky. He was holding out His hand toward me, and from there He protected me…

This vision seems fruitless, but it greatly benefited me because I was given an understanding of its meaning. A little afterward I found myself almost in the midst of that battery, and I knew that the vision was a picture of the world…But I’m referring to friends, relatives, and, what frightens me most, very good persons. I afterward found myself so oppressed by them all, while they thought they were doing good, that I didn’t know how to defend myself or what to do.43

How lucky you are: your ideal Father still protects you! What’s more, his protection has modulated. The ecstatic union has already become a matter of listening and hearing. From now on, and more and more, His Voice does not simply comfort and reassure you: it reasons, judges, ponders, counsels. You would never have succeeded as a foundress without pulling back from the Beloved a little. Where previously you were enclosed in a garden irrigated by pleasure, cut off from a world you perceived as rejecting you, His Voice has opened up an evaluating distance; the love-rapture has been amplified by understanding and a kind of mastery. In professional jargon, I’d say that the ideal of the ego has become endowed with a reasonable, domesticated, sympathetic superego. To build the little Convent of Saint Joseph’s, you followed David’s example: “I will hear what God the Lord will speak: for he will speak peace unto his people, and to his saints” (Ps. 85:8).

And with time, indeed, you will outdo David. Is that an overstatement, brought on by a fit of feminism? In 1577, the Voice you hearken to in prayer is that of Jesus himself as he tells you to “Seek yourself in Me” (Búscate en mí).44 Listening to the Other is not the same as seeking oneself in Him. Your inner experience is renewed; you are searching, you are a seeker; not content with hearing voices—divisions-hallucinations—you recompose, modulate, compose them. You write. David played on his harp while waging war, and he was a king. You are a warrior with no sovereignty beyond that of fiction in the Castilian vernacular. I can’t help thinking that your writing has more than one string to its harp.

Four years, the quietest and most restful of your life, had gone by in the company of the select group you gathered together at Saint Joseph’s,45 when a missionary friar fresh from the Indies told you of the horrors being perpetrated on the natives by the glorious peruleros whose adventurous freedom you had once envied.

Then the father general of your order, Juan Bautista Rubeo (Giambattista Rossi) arrived from Rome on his first visit to Spain. You were in dread of his opinion—but he only encouraged you to undertake further foundations, further afield. You acted surprised, but you were as ready as can be. It’s all you were waiting for. You got a little band of three of four nuns together and hopped into a wagon, under canvases stretched over a frame of rushes so nobody would see you, enclosure oblige—and off you went!

Did someone say “enclosure”?

And they’re off! At a trot, at a gallop, never at a walk, with detours, ruses, and ambushes galore, you’re a racehorse, Teresa, valiant and highly strung. A nun, with such a passion for the road? For the next fifteen years you will crisscross Spain, trudging on foot, mounted on a mule, rattled boneless in a coach. Escorted by a few devoted sisters and obliging men—secular priests who double as technical advisers, the occasional infatuated confessor—all undaunted by the hardships of nature and the iniquity of humans. Your energy as an epileptic prone to migraines astonishes your contemporaries, as well as posterity; from here, four centuries further on, it’s your tempo that fascinates me: you are a true composer of time.

Your impetus in this dash is loving and warlike. “Grant me trials, Lord, give me persecution!” Let’s go! Trotting, cantering, on horseback, on mule-back, in a coach, on foot! Bring your quills, your contacts, your wallets, your kind hearts! You, devout noblewomen, and you, knights and merchants, bishops and courtiers, kings and queens, let us mount and sally forth together in a glittering cavalcade, for the insidious enemy is on the prowl. But how to tell friend from foe? It’s war, the war of love.

If your blows fall short of the frail rampart, let’s sally forth again, to arms! I watch, I think, I burn, I complain, O love that fortifies my heart. Quick, each man to his post! The journey is in me, the battle too, brutal and furious: they alone can bring me peace. Peace, what peace? There is no peace. One hand alone cures and wounds me. And because my suffering never reaches its limits, a thousand times daily I die, and a thousand times am born, so far am I from my salvation. Here we go again, to horse, to horse, to horse, every soul a horse, there is no soul if not loving and warlike, warlike and in love.

All of a sudden the Babel of times and languages carries me away, too, me, Sylvia Leclercq, a therapist in my spare time, and suddenly Teresa’s tempo comes back to me in Italian: it’s the loving warlike gallop of Monteverdi,46 born fifty years after you, Teresa, my love; it’s his beat I hear drumming through your writings, rising, resonating, and harmonizing with you. Suddenly he supplies the sound I felt was missing as I read your texts. To lend meaning to his runaway music, the conductor at Saint Mark’s Basilica in Venice borrowed lyrics from Petrarch47 and from Giulio Strozzi,48 the first translator into Italian of Lazarillo de Tormes.

I hear you clearly now, Teresa, speaking to me in the voices of Petrarch, Strozzi, Monteverdi, all three Catholic Latins, and you excel in the race of love unto death:

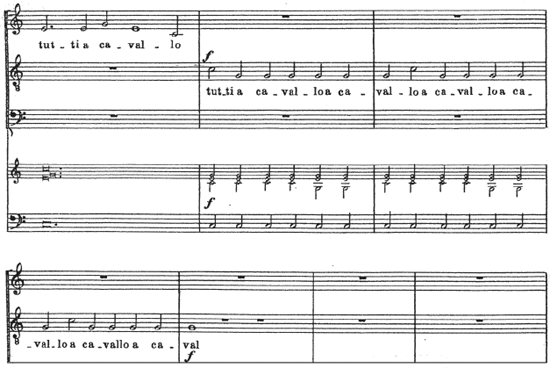

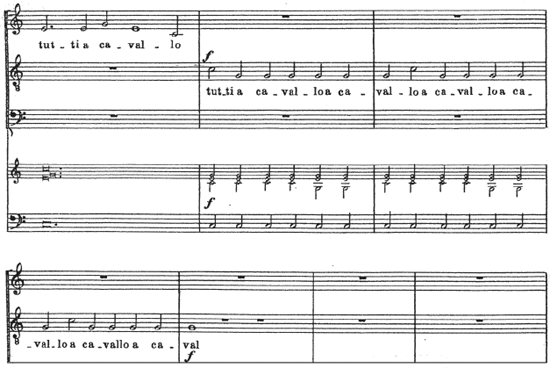

E E E E G E C

Tut-ti tutti a ca-val-lo…

E E E E G E C

Tut-ti tutti a ca-val-lo…

C G G G G G C G G G G G

Tut-ti a ca-val-lo a ca-val-lo a ca-val-lo a ca-val

Quick, love is near, as near as the enemy, every man to his post, not a moment to lose, to your souls, to your souls, to your souls, there is no soul but one that’s warlike and in love:

E E E E G E C

Tut-ti tutti a ca-val-lo…

When I was young I dreamed of writing like that, galloping off on a text by Strozzi or Petrarch to the rhythms of Monteverdi. Quite recently—had he sensed this hidden attraction?—a president (but which?) blurted out to me: “Sylvia Leclercq is a racehorse!” This strange compliment, which I received with a proud gratification that baffled the friends who were present, brought me back to you, Teresa, via my Italians:

E E E E G E C

Tut-ti tutti a ca-val-lo…

But it’s no good, I will never, ever, neither in body nor on paper, possess anything like your fever; your velocity, suppleness, abrasiveness, and cunning; your jubilation, humility, and perfidy; your sharp claws and soft lethargy; your dexterity with a deathblow; your violent triumphs and grievous defeats, simplicity and glory, suffering and sadism, annihilation and perseverance, carelessness and obstinacy, serenity and anguish, toughness and tenderness; your spiteful kindness, amorous indifference, and desperate tenacity. Nor will I ever have that furious, caressing lucidity and unflagging watchfulness, always on behalf of that infinite Love of the Other, infinitely unfindable, infinitely imbued in you. Never, Teresa, my love! You were, they said, a true “spiritual conquistador.”

It’s raining, snowing, blowing up a storm. You’re feverish, you throw up, you scourge yourself, you mount a bad-tempered mule that bucks you off, the axle of your coach snaps on a rutted road, you fall over, you hurt yourself, you break a leg, you feel cold, you feel too hot, there’s nothing left to drink, you haven’t had a scrap to eat since goodness knows when, you were promised great things but it’s all fallen through, never mind! You’ll find another way in, a different path; you’ll prevail on one of your accomplices, quick, no time to lose; your purse is empty but you always find money somewhere; it matters and it doesn’t, the re-foundation has no need of a steady income, as you explain to all and sundry, and also they—sisters, brothers, creditors, friends, or foes—don’t matter either. What matters are deeds, what’s needed are works and more works.

Your love leads the dance, that sole, single, inexhaustible love, on the trot, at a gallop, no love but in the loving warlike soul, and for that soul, your soul, galloping along the highways and byways of Spain, of the world, of perfection, of the interior castle, of everything, of nothing:

E E E E G E C, E E E E G E C.

Tu-tti, tutti a ca-val-lo, tut-ti, tutti a ca-val-lo

Religious houses founded by Teresa of Jesus.

1562 Saint Joseph’s in Avila

1567 Medina del Campo

1568 Malagón

1568 Valladolid

1569 Toledo

1569 Pastrana

1570 Salamanca

1571 Alba de Tormes

1574 Segovia

1575 Beas de Segura

1575 Seville

1576 Caravaca

1580 Villanueva de la Jara

1580 Palencia

1581 Soria

1582 Burgos

1582 Granada