“That is too high-minded,” I replied, “and consequently cruel.”

Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Humiliated and Insulted

I’m daydreaming, eyes wide open beneath their lids: I can see and hear her now, Teresa’s on her way, twenty years stretch ahead, counting from the first lines of the Life, and the only thing that will stop her is death. She’s got clean away from the family, from yesterday’s sisters, from the fathers of here or there, in order to be exiled in the Other and to carve Him a new place—invisible, impregnable, segregated from the world—in the world. She writes of transforming herself into God, uniting with God. At any rate, His Majesty cannot be winkled out of her. Neither “I” nor “we,” this dual entity sets off, arrives, struggles, founds, sets off again, battles with itself, starts over. Nothing but new beginnings. Let’s try to follow.

1567. Medina del Campo: a large market town with an international fair. Unexpectedly, wealthy converso merchants such as Simón Ruiz are prepared to back these nuns determined to live on nothing but alms and their humble crafts of embroidery and needlepoint…Did such fledgling entrepreneurs seek a place in the sun of the Church? Was it easier, more exciting, more promising to obtain this via innovators like Teresa, instead of hoary notables “who have the fat of an old Christian four fingers deep on their souls,” as Sancho puts it in Don Quixote?1 La Madre could not fail to interest them, for she did not comply with the estatutos de limpieza de sangre that excluded converted Jews from the more prestigious convents, as well as from university colleges and town councils.

Since she began making foundations, La Madre has been blessed with more than visions: voices, too, are heard, whose messages she eagerly transcribes. The difference is that visions induce states of rapture, whereas voices spur to action. The voices—obviously the Lord’s—speak disparagingly of human prescriptions and laws: they convey the Word of the Beloved differently from how the world’s kingpins understand it. To speed things up—and Teresa is moving faster every day—it seems that thanks to these voices she, too, stands against the law, against the world, against the grain. “You will grow very foolish, daughter, if you look at the world’s laws. Fix your eyes on me, poor and despised by the world. Will the great ones of the world, perhaps, be great before me? Or, are you to be esteemed for lineage or for virtue?”2

At Medina, then, a new house opens on August 15, 1567: cousin Inés Tapia, now Inés de Jesús, will be the prioress. There are malcontents in town who grumble that this foundation is a fraud. Let them say what they like, God has given Teresa some true friends here: Pedro Fernández, the Dominican principal; the Jesuit Baltasar Álvarez, who accompanies La Madre in her spiritual life; and the Dominican García de Toledo, of course, dependably busy and protective, almost affectionate. No sooner has this inauguration been celebrated, than permission arrives to found two male monasteries under the Primitive Rule! Where should they be located?

Antonio de Heredia (Antonio de Jesús), a Carmelite of the Observation from Medina, takes an interest. But he’s too old, too difficult, Teresa balks, no. Let’s speed up:

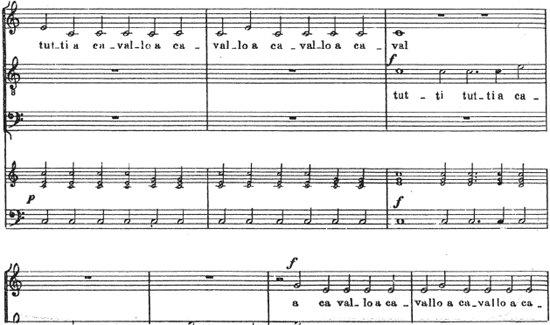

tutti, tutti a cavallo

tutti, tutti a cavallo

tutti a cavallo a cavallo a cavallo a cavallo a cavallo a caval

tutti, tutti a cavallo

tutti a cavallo

Father Antonio introduces to the discalced nuns a bright young man fresh out of theology school at Salamanca, twenty-five-year-old Juan de Yepes, ordained as Juan de San Matías. Short and skinny, round-skulled and sharp-faced, he is the son of a rich weaver from Toledo (Toledan forebears and of Jewish stock, it seems—just like Teresa!), the hidalgo Gonzalo de Yepes, who was reputedly ruined by marrying Juan’s mother, a woman of Moorish and hence Muslim blood. This Juan de San Matías is an ascetic, disillusioned by the calced life; he yearns to withdraw from the world in the mountains of Segovia. He has shining eyes, an elliptical wit, and the fieriness of the Carthusians he wanted to join. He’s the one! Onward!

No, hold your horses, wait!

Luisa de la Cerda, Teresa’s generous patron and friend, slows things down again. This noble lady, who aspires to Heaven above all else, insists, absolutely insists that Teresa found a branch at Malagón, a little hamlet in the sticks. Teresa can’t see the point of dispatching her nuns to the middle of a field, when all they know is weaving and sewing. But Báñez is keen as well, and it’s hard to say no to him. Aha! Malagón, as she recalls, is not a million miles from Montilla, the home of Juan de Ávila. Doña Luisa, who often visits Andalusia, could deliver to him the manuscript of the Life, which Báñez has just returned to the author. Shush, not a word to Báñez, who doesn’t want the text to circulate and might feel sore if the other priest were roped in; best to take responsibility oneself and entrust the precious pages to Luisa. The foundress has embarked on a new chase. How to make sure her manuscript will reach its destination? It would seem writing a book is no less complicated than founding a new religious order!

To begin with—she’s always beginning—she must get in touch right away with Juan de Ávila, tell him of her forthcoming visit to the area, and send him the book in advance through Luisa. Although she dared to hope as much, Teresa is thrilled when the learned sage replies without delay and even looks kindly upon her journey: “You can better serve the Lord with this pilgrimage than by staying in your cell.”3 No hesitation, she’ll go to Malagón.

Meanwhile there’s no end of checking, finding out, keeping up to date: they stop in Alcalá de Henares on the way, at the discalced convent founded by María de Jesús. Poor woman, she hasn’t got a clue: too tough, too many penances. María is an innovator whose notions came in useful for the Constitutions, to be sure, but only on condition of being revised through and through, adapted to inner virtue, stripped of external rigors. That’s also what it means to be a foundress: the readiness to start over, over and over again, relying on one’s powers alone—besides the Voice of His Majesty, of course!

The problems pile up at Malagón. Where to find a spiritual director for a new monastery in this godforsaken spot? How about getting Tomás de Carleval from Baeza, Bernardino’s brother, a disciple of Juan de Ávila…But Bernardino was arrested by the Inquisition back in 1551. It might be reckless, a way of courting trouble.

On the other hand, attentive to the guidance of the master of Avila, Teresa doesn’t think twice before accepting converts at Malagón, that is, sisters in white veils, and starting a school for local girls. The young recruits have got to learn to read, otherwise they haven’t a hope of donning the black veil one day and reading the holy office!

And then, since troubles never come singly, how on earth is one to eat fish, as stipulated by the Constitutions, when there’s no fish to be had in Malagón? Never mind, let them eat meat, we’re in Spain after all, a carnivorous country if ever there was one, and too bad for the Constitution, decrees Teresa. Off they go again.

E E E E G E C

Tut-ti tutti a ca-val-lo…

E E E E G E C

Tut-ti tutti a ca-val-lo…

C G G G G G G C G G G G G

Tut-ti a ca-val-lo a ca-val-lo a ca-val-lo a ca-val-

C G G G G G

lo a ca-val-lo a ca-val

But it’s not that simple. La Madre does not for a moment forget about her manuscript: the Business she must attend to amongst her business.

May 18, 1568. Letter to Luisa de la Cerda: Why has she not yet sent the book of Teresa’s Life to maestro Ávila?

May 27. Another letter to Luisa. “Since you are so near him, I beg you…” Not to mention that Fray Báñez is also waiting on it, and since there is no way to photocopy the original, and Báñez must not find out about the author’s contacts with Juan de Ávila, “I’m distressed—I don’t know what to do.”4

June 9. Fresh bid to jog her ladyship’s memory. “In regard to what I entrusted to you, I beg you once more…”5

June 23. “Remember, since I entrusted my soul to you…”6

November 2. At last! “You have worked everything out so well…So I’m forgetting all the anger this caused me.” Juan de Ávila has emitted a positive verdict, the future saint “is satisfied with everything. He says only that some things should be explained further and that some terms should be changed.”7

Good grief! It took all of five letters to Luisa de la Cerda during that summer of 1568 to set the ball of the Life’s acceptance rolling: not that Teresa was really “attached” to the text, at least she claimed not to be; but it’s not that simple. Was it not essential for her to write down (or to “communicate,” as we say today) the “treasure” she concealed in her “center,” so as to found an interior Time within time as it flies by?

Summer 1568. To Valladolid. A great Mendoza, Bernardino of that name, wishes to settle the Discalced Carmelites into a house there, with a garden and vineyards. She cannot refuse, when the gallant gentleman is brother to the bishop of Avila, Álvaro de Mendoza, who blessed the foundation of the Convent of Saint Joseph’s in Avila!

Teresa stops off at Duruelo to visit the little house additionally offered by Bernardino, with a view to setting up the first convent for discalced monks. She makes a detour to Medina to bring back Juan de San Matías, promoting him to the rank of associate founder in the Valladolid venture.

Let’s see, how are we getting along in these noble lands so handsomely lavished upon us? There are so many mosquitoes in this lovely countryside that the sisters get malaria and die like flies. Teresa won’t be bullied, enough is enough, we’ll move into town. Álvaro’s sister María de Mendoza donates another house, it’s just what we need, we’ll put up all the fittings ourselves: cells, chapels, grilles, Teresa won’t settle for less than perfection; María Bautista will be the prioress. La Madre wants everyone to know that a convent must be to La Madre’s taste, she won’t bow to pressure from any quarter, whether the Mendozas or some estimable Jesuit such as Fr. Ripalda.

Four years later, on March 7, 1572, Teresa writes to inform María de Mendoza that she will not accept two postulants recommended by that lady. Is it because by her high standards, the young ladies showed an insufficient vocation? She’s a perfectionist, as we’ve seen: she doesn’t want one-eyed or sickly girls in her convent.

You’re hard-hearted, Teresa, and you know it, you’re proud of it, you’re not as Christlike as your voices make you out to be. A masochist overall, you are not above being a sadist at times, I will remind you of that. It helps, certainly: the times are as tough as you are, the Carmels hard to control, one has to fight, to keep tense as a bow in order to keep making foundations. But still!

The previous year, an auto-da-fe was held in Valladolid. Men and women accused of Lutheranism were burned at the stake. Most were conversos with connections to the Cazalla family; Agustín Cazalla, preacher to the king and his mother, was among them. There had been some contact between these circles and doña Guiomar, involving Teresa herself: although they were no longer in touch, prayer continued to link them. The world was coming down hard on the new paths she was trying to clear, it was out to silence His Voices, that much was clear. Oh well. Just distrust everyone and everything, follow your way of perfection more and more perfectly, and we’ll be off again,

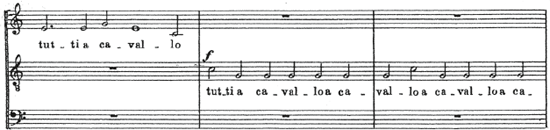

E E E E G E C

E E E E G E C

Blessed be His Majesty, this hostile world is not only composed of enemies: some pure souls do exist, like that young Juan de San Matías. Might His Majesty have created him expressly for Teresa’s project? His is a life devoted to intelligent thought and great penance; “I believe our Lord has called him for this task.”8 In November 1568, Juan and Teresa, now a close-knit team, founded the masculine Convent of Duruelo. A shabbier, more frugal holy house can scarcely be imagined. Teresa stitched with her own hand the habit of the young monk who now took the name of Juan de la Cruz, John of the Cross.

And yet you are going to abandon him in the dark night of this utterly impoverished place, Teresa, my love, a pang of sorrow and pride in your heart, admiring him, but already a little distant. For he is passionately in thrall to the realm of the invisible, whereas you are committed to scattering the glints of the diamond of your soul, which encases the Third Person. John of the Cross will lose himself ever more in the purity of agonized contemplation, whereas you pursue your furious cavalcade for God.

F F F F A♭ F D♭

F F F F A♭ F D♭

D♭ A♭ A♭ A♭ A♭ A♭ A♭ D♭ A♭ A♭ A♭

A♭ A♭ D♭ A♭ A♭ A♭ A♭ A♭

F F F F A♭ F D♭

F F F F A♭ F D♭

Yes, I hear you clearly: after every conversation with John of the Cross, your gallop is slightly faster and yet slacker, dampened by melancholy. No, John’s nothingness will never crush the jewel of your inner dwelling places, it can only unleash a shiver in that heart of yours, which wants to be hard, which has to stay that way.

Now then, time to pull yourself together, to check your first foundation and tighten the bonds with the sisters at Saint Joseph’s in Avila. Indeed, but it’s impossible! A fresh proposal has arrived, supported by your new Jesuit friend, Pablo Hernández: to found a house in Toledo.

Toledo, is it? The city where grandfather Juan was traduced, where the sambenito embroidered with the Sánchez family name was hung up in the church of Santa Leocadia. A metropolis that presently numbers no fewer than twenty-four monasteries! A foundation in such a place is a crazy gamble! Maybe so, but that’s what La Madre likes about it.

A rich trader named Martín Ramírez has engaged to bequeath his worldly goods to the discalced institution at Toledo; in exchange, he wants to be buried in the chapel. Is this acceptable? A commoner giving himself the right to be buried in a convent, as though he were a nobleman? It goes without saying, however, that they will welcome the daughters of converso Jews. But Toledans are sharply divided over the fate of Archbishop Bartolomé de Carranza, arrested in 1559 and slammed into a Roman jail due to his friendship with Luis de Granada and other “spiritual” adepts of mental prayer; he has numerous enemies here. Some pious women nevertheless club together to have him freed, defying the Inquisitor General Fernando de Valdés. As though this were not enough to torpedo the Toledo venture, it soon transpires that the Ramírez bequest is no longer available; the permission to found keeps being delayed, and conservatives rail against the cheek of this little woman who proposes to found a religious house by cutting deals with tradespeople! Can anything else go wrong?

No need to panic. Teresa, who can be sweet and gracious when she chooses, pushes on with the works. Finally the ecclesiastical governor of the diocese, don Gómez Tello Girón, agrees to guarantee the project, on one condition: in order to avoid infection by the taint of trade, the convent must have no revenues and refuse any donation or patronage (thus shutting the vulgar Ramírez out of the picture; was he the problem all along?) The foundress feigns surprise. But Father, who suggested anything else? Our Constitutions impose a strict rule of poverty, I thought you knew.

Mother Teresa has three or four ducats to her name, enough to buy two straw pallets and a blanket. A mischievous pícaro who goes by the name of Alonso de Andrada offers help, in the form of the keys to a building he’s wangled who knows how. Teresa prefers not to inquire about such details, especially when they give off a whiff of irregularity. She is physically attacked by a neighbor, who hates the discalced movement. None of this prevents her from persevering with the work in hand—sweeping, repairing, and decorating the premises. At this point the owner of the place changes her mind, decides she doesn’t want the newfangled style of convent either. But at last Tello Girón returns from a trip, and the council grants permission. The happy ending is courtesy of the Voice of the Lord, who has demanded superhuman obstinacy from Teresa, mixed in with a degree of machination and shady dealings, it must be said.

On May 14, 1569, the first Mass is said in the new foundation at Toledo. More than a foundation, it has been a brilliantly forced passage, a seduction strategy, a feat of errancy and endurance. Nothing can resist you, Teresa. Perhaps your poverty is a form of high ambition? Your humility, a piece of brazen chutzpah?

E E E E G E C

E E E E G E C

This gallop might have been smoother had it not clashed with other equally bold and no less brash schemes, usually from women. At this precise juncture, your soaring energy came up against that most formidable of Spanish grandees: Ana de Mendoza de la Cerda, princess of Eboli, wife of Prince Ruy Gómez—the most powerful personality after King Philip II—and great-granddaughter of don Pedro González de Mendoza, cardinal and archbishop of Toledo, dubbed “the third king of Spain.” Quite a package! She was a haughty, peremptory woman, minus an eye (could that be another reason why you didn’t want that sort of defect in your convent, Teresa?), capable of setting fire to everything around with “just one sun,” as the saying went, a spoiled and spendthrift princess. You were about to find this out, unfortunately, for here she was, nagging you to drop everything and go to Pastrana to found another convent, there’s no end to it. Off you went, willingly enough, since in the intoxication of your status as the go-to foundress, giddied by your ascent, you were still blind to the traps the Eboli woman would set for you, my naive Teresa.

No question of a wagon this time, it’s an unworthy vehicle for a Madre like yourself. The princess sends a stately coach, a fairy carriage! Along the way, your gallop—a golden gallop now—draws breath at Court, in Madrid! We know that His Majesty’s Voice is essential to your foundations, but that of King Philip II is not to be sneezed at either, is it?

The great ones of this world are solicitous, they promise to help. The great ladies are not to be outdone: Leonor de Mascarenhas, for instance, introduces you to a pair of hermits who will become your disciples, or almost. One can never be sure of seeing eye to eye with such original characters, but you’re an original yourself, aren’t you? The characters in question are Mariano de Azzaro and his friend the painter Giovanni Narducci, of whom more later.

At Pastrana you are given a suite in the Eboli palace and showered with treats, fueling the gossip of evil tongues: what behavior from a woman who always purports to be holier than thou! And yet sparks have flown between you and your hostess Ana de Mendoza from the beginning of your stay. You of course have no time for the courtiers and their “artificial displays” of lordship (autoridades postizas),9 and you say so bluntly. For her part the princess insists on an Augustinian sister to keep you company, although it is common knowledge that you only care to frequent nuns affiliated to your own discalced Rule. And so on. Eventually you settle on a prioress: Isabel de Santo Domingo, the spiritual daughter of the great reformed Franciscan Pedro de Alcántara who was such an inspiration to you, as we’ve seen. And a second monastery for men takes shape not far away, this time under the auspices of the prince of Eboli.

A change of decor is noticeable here: luxury congeals into morbidity and the atmosphere is sepulchral. As at Duruelo, the monks’ cells are adorned by crosses and death’s-heads. The hermits you recently met, Azzaro and Narducci, have renamed themselves fray Ambrosio Mariano de San Benito and fray Juan de la Miseria—that’s right, the painter whose portrait of you you weren’t too pleased with. These two introduce the practice of perpetual worship to Pastrana: night and day, the Holy Sacrament must be attended by two praying brothers! This overwrought asceticism is as distasteful to you as that of young John of the Cross. The mournful rituals at Pastrana and Duruelo are beyond you; impressed but already somewhat detached, you think only of continuing the journey.

E E E E G E C

Tut - ti tutti a ca - val - lo

E E E E G E C

Tut - ti tutti a ca - va - lo

Her Highness of Eboli can stay put, she’s got what she wanted, her very own Carmel, like her relatives María de Mendoza and Luisa de la Cerda; in fact she’s got two of them. Let her stay in Pastrana, you won’t be climbing into her golden coach again, that’s a solemn vow; there have been too many compromises already.

The galloping is far from over, and you are more and more attentive to His Majesty’s Voices so that they might speak through your lips. Voices that dictate the proper balance between the gruesome penances favored by the recently discalced, and the worldly temptations entailed by princely palaces, but also by convents with questionable standards: between macabre skulls and the licentiousness of paradisiac illusions. The followers of Juan de Ávila and the Jesuits are alone in hearkening to those voices in your mouth; they alone hear you at this time, one of the most testing of your whole itinerary. Isn’t that enough encouragement to press on?

Meanwhile, family ties must be reorganized. You relegate the family of your sister Juana de Ovalle to its rightful place: too much familiarity is damaging. On the other hand you empower the role of your brother Lorenzo, who has returned from the “Indies” with a splendid fortune and a burning faith. It’s a good time to regulate your relationship with money: not too much but more than none, just enough for peace of mind and galloping on, but even so…Whatever the precautions, money comes at a price, and one that’s always too expensive. “Miserable is the rest achieved that costs so dearly. Frequently one obtains hell with money and buys everlasting fire and pain without end.” (“Negro descanso se procura, que tan caro cuesta. Muchas veces se procura con ellos el infierno y se compra fuego perdurable y pena sin fin.”)10

Fall 1570. Departure for Salamanca, this time. Another Jesuit, Martín Gutiérrez, has asked Teresa to start a house in this city of students and high-flown culture. Where can premises be found to rent in such a densely populated place? The Dominican Bartolomé de Medina is displeased: from the heights of his university chair, he advises the “little woman” to “stay at home.” Teresa trusts in her powers of persuasion. All she needs to do is pay a call to this snooty academic, and he’ll drop into the bag of her rhetoric like so many others.

Done: the inauguration is scheduled for November 1. The locale has not yet been decided, everything is provisional, but the main thing, the foundational gesture, has been achieved. The rest will follow. Ana de Tapia, now Ana de la Encarnación, has been chosen as the prioress.

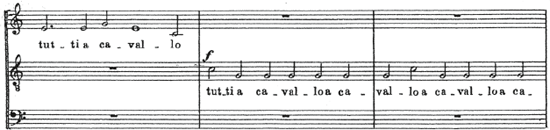

Tut-ti tuttia ca-val-lo tut-ti tuttia ca-val-lo

tuttia caval-loa caval-loa caval-loa caval-loa caval

E E E E G E C, E E E E G E C

No chance of going to sleep on one’s laurels. At Medina, a new prioress must be appointed. The Carmelite provincial, Ángel de Salazar, uneasy about the reforms from the start, is opposed to the re-election of Inés de Jesús. He would prefer to have an unreformed nun from the Convent of the Incarnation; he is, moreover, backing the claims of the family of Isabel de los Ángeles, Simón Ruiz’s niece, fearful lest her fortune—money misery again!—be handed to the convent at their expense. Salazar angrily orders Teresa off the premises: what an excruciating humiliation! There will be no more galloping for a while, as she slinks crestfallen out of Medina on the bony back of a water-carrier’s donkey. She goes for succor to John of the Cross, and together they set off to make a foundation at Alba de Tormes.

January 1571. An accountant at the court of the dukes of Alba, prompted by his wife Teresa de Layz, had already called on Teresa to establish a convent in the rural surrounds of Alba de Tormes. By now, the foundress has learned the hard way that some minimum income is necessary, simply for the convent to exist and the sisters to live: in those days, many succumbed from their penances but also from starvation. She strikes a bargain: you will provide for food, clothing, and the needs of the sick, and accept all vocations without inquiring into “purity of blood.”

As always, La Madre travels to the sound of His Voice. Tested to the limit, but more than ever sure of the Other, Teresa is definitively a Third Person, you can’t miss it. A writer who outlines her own character, combined with a pragmatic woman—that’s what you call a foundress. Martin Gutiérrez, a few years younger, the rector of the Society of Jesus college in Salamanca,11 understands and supports her; but doesn’t their intimacy jeopardize her liberty? Since, she tells his Reverence, “I don’t think I’m attached to any person on earth, I felt some scruple and feared lest I begin to lose this freedom.” The Lord’s Voice responds promptly to this attachment anxiety, and reassures the troubled woman beneath the Carmelite habit: “Just as human beings desire companionship in order to communicate about the joys of their sensual nature, so the soul desires when there is someone who understands it to communicate about its joys and pains; and it becomes sad when there is no one.”12 Communication between souls, on a par with the sensual joys, is therefore not altogether banned between the Jesuit and the nun. That is certainly good news. Otherwise, how could she possibly proceed with making her foundations?

The Dominicans prove more resistant, this time, to Teresa’s charms. Pedro Fernández, the illustrious theologian who defended Teresa in the early days of her project, has gone over to the side of the provincial, Ángel de Salazar, who remains suspicious of it, as we’ve seen, and has begun to express his own reservations. Fortunately the Voice of His Majesty is once more on hand to confront the Dominican father who has become such a père-sévère: every time Fr. Fernández reproaches her for some failing, the Voice brings Teresa back to life. It’s perfectly true that I am incompetent and a sinner, Father, is the gist of her retort; but your objections help me to improve. I am profoundly grateful to you, for if I surpass myself it’s thanks to you, please don’t stop, it’s going rather well, don’t you agree? It’s going well, and better, and faster. Dash on!

tut-ti tut-ti a cavallo

tut-ti tut-ti a cavallo

tut-ti a cavallo a cavallo a cavallo a cavallo a cavallo a caval

tut-ti tut-ti a cavallo

tut-ti tut-ti a cavallo

October 1571. As the apostolic visitator to the Carmelites, the same Dominican father, Pedro Fernández, appoints Teresa as prioress to the Incarnation in July 1571. Such a strange idea must be the brainchild of Provincial Salazar—that would make sense. Being so deeply opposed to her foundations, it would suit him to nail her down inside a convent of 150 nuns, while appearing to honor her with a promotion! It’s nothing but a punishment, and Teresa sees right through it, as she writes to Luisa de la Cerda: “Oh, my lady, as one who has known the calm of our houses and now finds herself in the midst of this pandemonium, I don’t know how one can go on living.”13

The investiture ceremony goes horribly wrong. Afraid to lose their freedoms as calced nuns, the conservative Carmelites won’t let Teresa in. Protests, booing, and jeering greet the provincial when he utters the name of the Incarnation’s new prioress. “No!” shriek the incensed sisters. The only contrary opinion comes from Catalina de Castro, who pipes, almost inaudibly: “We want her, we love her!”

This staunchness is all it takes to rally a small, timid group of supporters. The antis grow heated; the timid camp grows larger. Scuffles break out. The constables are called in. At last the controversial prioress manages to slip inside the choir by the side door. Clutching an image of her father, Saint Joseph, Teresa sits down in the same stall she had occupied for twenty-seven years, when she was just a little nun. A blunder, in the daze of emotion? Or, on the contrary, a clever diplomatic ruse, a conscious diffidence that is sure to pay off? No, rather a divine inspiration. And that’s just the beginning.

You are a mistress in the art of mise-en-scène, Teresa, my love. Oh yes, don’t misunderstand me, the right judgment of mise-en-scène is an art, like music, a kind of sanctity. Then you disappear for a moment, and return with a statue of our Lady, dressed in embroidered silk. Slowly and solemnly you place her in the prioress’s stall. You give her your official keys, you kneel at her feet and say in a soft voice (yours or His Majesty’s?):

“Behold our Lady of Mercy, dear daughters. She will be your prioress.”

Your words fell the rebels like a bolt of grace—a coup de foudre, indeed. From that moment on, the Incarnation was yours. No more insistent visitors, sensual dissipations, flirting in the parlor. During Lent, even fathers and mothers are excluded.

All the same, this new and unaccustomed rigor is not accepted by your subordinates without a struggle. It’s only human. A party of enterprising young blades decides to have it out with you: Does this prioress think she’s God? You receive their spokesman and continue spinning, without looking at him, through a torrent of cavalier eloquence. Finally you cut in:

“Henceforth Your Grace will kindly leave this monastery in peace. If Your Grace persists, I shall appeal to the king.”

Notwithstanding such smart raps on the knuckles, you are still a good mother who knows how to feed her daughters, I grant you that, my fixer Teresa. Francisco de Salcedo is in charge of provisions: sixty head of poultry, plenty of pulses, lettuces, and quinces. Your sister Juana is going to send some turkeys. All of the ingredients for some ollas podridas, as well as salpicón, perhaps, and endless supplies of yemas, my chum Juan would be delighted! The fine ladies of your acquaintance—the duchess of Alba, doña María de Mendoza, doña Magdalena de Ulloa—will contribute as much and more.…You are not anorexic, Teresa, or not any more, it’s a false rumor extrapolated from your early days. But you forbid jewelry and profane dances, it’s the least you can do. His Majesty knows only the music of angels and the spirit, and you do likewise.

The one thing lacking in this refashioned Carmel is a good confessor, and you know just the man. Summoned from the college in Alcalá where he was teaching the prince of Eboli’s novices, John of the Cross takes the post. The ideal circumstance for conversing with this holy man: among mutual ecstasies and levitating chairs (phenomena certified by the nuns who keep an awed eye upon the sayings and doings of the two protagonists), the pair of you advance together and yet on different tracks toward your respective sainthoods, divergent but forever convergent.…The sort of love you share, lucid and remote, is only possible this way.

The moment of spiritual marriage has arrived at last. We are in November 1572. The holy humanity of Jesus inflicts wounds on you that match His own, and lavishes immeasurable joy upon you, since you’ve succeeded in pleasing Him by your prayers as by your deeds, in ficción as in obras:

While at the Incarnation in the second year I was prioress, on the octave of the feast of St. Martin.…His Majesty…appeared to me in an imaginative vision, as at other times, very interiorly, and He gave me His right hand and said: “Behold this nail; it is a sign you will be My bride from today on. Until now you have not merited this; from now on not only will you look after My honor as being the honor of your Creator, King, and God, but you will look after it as My true bride. My honor is yours, and yours Mine.” This favor produced such an effect in me I couldn’t contain myself, and I remained as though entranced. I asked the Lord either to raise me from my lowliness or not grant me such a favor; for it didn’t seem my nature could bear it. Throughout the whole day I remained thus very absorbed.14

Throughout all this you make an excellent prioress, ergo your mission has been accomplished. But Avila does not suit you, the climate is icy, you’re surprised you could ever have been born here. It’s time to go on the road again.

New foundations await you.

Fussier than a Lutheran, more illuminated than an alumbrada, you are a magnet for condemnation but also for hope, hopes of all kinds. You are a pioneer of the Counter-Reformation and a saint; they don’t know that yet, but they will after your death. But there are some who suspect it and go out of their way to smooth yours. People like the duchess of Alba, who obtains permission in February 1573 for you to leave the Incarnation for a few days and go stay with her. Shortly afterward you receive authorization from Pedro Fernández, the apostolic commissary, to establish a house in Segovia.

1573. One of Teresa’s confessors, Fr. Jerónimo Ripalda, comes to Salamanca as La Madre is passing through, in the course of her three years at the Incarnation; he instructs her to write down the story of her foundations. Following on your autobiography, now tell us about your work. How impatiently you had waited for this! The text had been flowing ever since the final chapters of the Life. The Voice had suggested you write the book in 1570, and nothing had come of it. Now, you feel founded enough to be able to pass on the art of founding.

Ten years ago, after all, the act of writing had spurred you to make foundations. Conversely, now, the creation of your godly houses redirects you to writing, a different writing in which psychological subtlety, a hardheaded sense of reality, and the lucidity of rapture are intermingled. You begin work on August 24 and compose the first nine chapters of the Foundations. One certainty bolsters you: having managed to flesh out your visions in the real world, you are confident they don’t come from the devil. “So after the foundations were begun, the fears I previously had in thinking I was deceived left me. I grew certain the work was God’s.”15

From 1573 to 1582, the Foundations relate the loving and warlike adventures of Teresa the politician. They are the visible face of another adventure, the one that invented the depths of intimacy, as related in The Interior Castle. In 1577, at the request of Fr. Gratian and the order of Fr. Velázquez, her current confessor, the Carmelite penned the latter text, which would “found,” effectively, dwelling places that appear, with hindsight and against the background of the Foundations, to be the antithesis of the worldly business of the militant traveler. Or were they instead the ultimate condition for the success of those pragmatic endeavors? Perhaps it is a case of a foundation of the foundations, since at this point—halfway through the time it will take to reform the Carmel and at the very heart of Teresa’s personal experience—the demons confronted and trounced on the outside had not disappeared altogether. In her private and most intimate depths they teemed, in the form of numberless mental and emotional resistances to be overcome, walls of the soul to be broken through, an inner mobility to be made suppler. The exterior war was sustained by interior analysis. She had no shield, it was simply the elucidation of the inner self, made fluid and habitable, that enabled Teresa to live in the present, past, and future time and world. “To live” henceforth meant to overcome the fear of hatefatuations that cannot be other than diabolical, and the agony of obstinately morbid symptoms, in order to be continually reborn inside, while tirelessly forging ahead outside. At the sunset of the Golden Age, the foundress’s constant peregrinations across the arid lands of Spain, her conflicts with Church institutions, all of which were pretty well obsolete and derelict, and her wrangles with their convoluted administrations drew strength from that interior journey, which achieved the construction of a space of wholesale serenity: “a jewel,” she calls it in a letter to Fr. Salazar.16 And The Interior Castle closes upon Jesus alone, among enamels more delicate than ever, gold and precious stones—mystical graces unseen, hidden in anonymity, and yet flashing forth. Tensions and charms of the…baroque: barroco, an irregularly shaped pearl.

Once again it was in writing that Teresa erected her ultimate habitat, entered into so it might be publicly revealed. Here is an irregular space if ever there was one, made of antitheses, strong images targeting the senses and aiming to dazzle, to unbalance, to set in motion, to celebrate the inconstancy of feeling in a perpetual mobility that can only be appeased by profusion and the eternity of the ephemeral. The recesses in the cut of these precious stones, these luminous diamonds studding the fabric of Teresa’s text, render them surely more decorous, less boldly ostentatious than the institutional work of reform? More private, allegorical, and polyphonic than the very real epic of the foundational race?

That’s not how Teresa saw it. From early on in the Life, by dint of prayer, she was always struggling to extricate herself from “the teeth of the terrifying dragon,”17 the devil, so as to sing the praises of God’s goodness and mercy; “that I may sing them without end”!18 By the time of the Interior Castle, secure in the knowledge of being the loving and loved spouse, she builds an interior space of impregnable riches that, opening up room by room in parallel to her race, is capable of withstanding real setbacks in as much as it challenges Hell itself—that placeless place, that gash in the soul, that unrepresentable trauma that makes you die of fear and diffuse excitement, whose horrors La Madre once described at length to her sisters at the Incarnation.

Today, as her race through the world crosses with her surge toward the Beloved within, at the intersection of Foundations and Dwelling Places, Teresa has just made a “baroque” discovery—as we will understand later—which enchants her: bliss beats torment if, and only if, the soul manages to inhabit itself in such a way as to perceive itself as a generous polytope, a kaleidoscopic mobility sustained by the Other’s love. Thus at ease in her spacious interior, she can defy the cramped Gehenna as well as the demonic alleyways of worry in which the couples and groups of creatures confront one another. With its dwelling places thus equipped and made good for enjoyment, the soul can endow itself with a new imagination, fertile in strong and serene ramifications within and without. The antics of the devils, by comparison, appear as what they are: deadly substitutes spawned by another imagination, the kind Teresa calls “weak,” illusory because constrained, intimidated, frozen by the fear of external or internal aggression, wearisome and worn out, defeatist—in a word, melancholic. The soul in love with the Other and loved by Him at the core of itself well knows that the Enemy, that is, the devil, has no reality beyond this wretched counterfeit imagination. But rather than exhaust itself in sterile wrestling, the fortified soul in its dwelling places transmutes that cringing imagination into a triumphal one, deft at assimilating the infinite facets of the logics of love.

“For even though it may seem that good desires are given [by the devil], they are not strong ones.”19

It is in the imagination that the devil produces his wiles and deceits. And with women or unlearned people he can produce a great number, for we don’t know how the faculties differ from one another and from the imagination, nor do we know about a thousand other things there are in regard to interior matters. Oh, Sisters, how clearly one sees the degree to which love of neighbor is present in some of you, and how clearly one sees the deficiency in those who lack such perfection!20

How can we identify the souls with a high degree of “love of neighbor”? The judgment of the inside-outside traveler is instant: those incapable of true love are those she observes as “earnest” and “sullen,” who “don’t dare let their minds move or stir.” “No, Sisters, absolutely not; works are what the Lord wants!”21

Bestir yourselves, then, get moving, body and soul, send your thoughts on a journey: tutti a cavallo, inside and out! Be swift, don’t ever stop, don’t fasten on anything, neither on yourselves nor on the one you love, for the Other is always elsewhere, a bit further on, a step ahead, go on, keep going! Do something not for the love of this or that person, but because that’s how it is, a given, given by the good Being himself, it’s the will of our Master, if you like, for the Good runs through us. “It” is beyond our ken because it loves us. That is why, if we are truly to participate in the will of the good Being, it is important to seek, always and above all, that delicious and peaceful gladness that disconcerts our exterior being and thwarts all those chicanes, which can only be external, minor, and thus deceptive. There is a great difference in the ways one may be, the infinitely good Being desires its own bounteousness and appropriates itself indefinitely, penetrates and travels its own being, like the time of the characters in Proust; the time of its racing extends into space, reversible dwelling places hatch and stack up ad infinitum, evidently.

It’s clear from inside the plural and delectably amorous intimacy of my moradas that “the devil never gives delightful pain like this.” Oh, I know Satan is capable of affording us tidbits and pleasures that can seem spiritual, but it is beyond his power to join great suffering with quiet and gladness of the soul; the devil does not unite, his work is always a scattering. Likewise “the pains he causes are never…delightful or peaceful but disturbing and contentious,” whereas the “delightful tempest comes from a region other than those regions of which he can be lord.”22 Thus Teresian interiority effects a masterly transformation of Saint Augustine’s regio dissimilitudinis, created by original sin, for which the Protestants were developing such an appetite. No doubt about it, the muy muy interior is nothing less than Heaven down here on earth.

But then, if the questing soul is certain of its reciprocated love for the Other, what pains it? What greater good does it want? Another discovery, as baroque as the last, comes to resolve this dilemma in your writing, my blissful Teresa. As with the inconstancy of the Divine Archer who, like the Spouse of the Sulamitess, comes and goes in His nevertheless absolute goodness, and whose wounding “reaches to the soul’s very depths” before He “draws out the arrow,” the pain, like the soul, “is never permanent.” It’s as though a spark leaping out from “the brazier that is my God” so struck the soul that “the flaming fire was felt by it,” but “not enough to set the soul on fire,” so leaving it with elusive pain; the “spark merely by touching the soul produces that effect [al tocar hace aquella operación].” An arousal the more exciting for being unsatisfied, a pleasure forever unconsummated, the “delightful pain” remains nameless, fluid, without identity. It is “pain” and “not pain,” and this uncertainty—baroque in itself—means that it is fluctuating, “not continuous,” mutable and tantalizing to the end. “Sometimes it lasts a long while, at other times it goes away quickly”; the soul in search of loving interiority is not master of itself, it always depends on the Other…although the Other is within it, like a blinding flare. The insatiable seeker, never quite ablaze, begs for more, for as soon as the spark makes contact it goes out, and the desire for pain—or is it pleasure? No term seems right for this erratic, multiple state (porque este dolor sabroso—y no es dolor—no está en un ser)—once more stokes up “that loving pain [He] causes.”23

Frigidity? Masochism? Voluntary servitude compensated by a runaway imagination? Good old Jérôme Tristan, beating us over the head with his diagnostics, my mercurial Teresa. He’s right, no doubt, but it’s more than that. If that were all, it’d be the devil’s work. On the contrary, in your penetration-appropriation of the good Being by itself, this operation “is something so manifest that it can in no way be fancied. I mean, one cannot think it is imagined, when it is not.”24 The test of the imagination by the senses emerges as the ultimate proof of the truth of the experience, unmistakably stamped with the Other’s trademark, not that of the devil. Kinetic, sensitive, bittersweet, the endlessly relaunched imagination (“again!”) with its exorbitant intensity and rosary of metaphors, creates the geometry of an authorized serenity, authorized because shared with the ideal of the Self, the ideal Father. Touching, sparks, braziers, extinctions, pains…and again…and again…and again! “Lack,” “frigidity,” “masochism,” you say? All that is nothing but trials sent by the devil, fit to be reversed into an infinite winging toward the space packed with obstacles overcome, toward the capacity for love proper to the Beloved incorporated in me. Toward the Other who is Love, inaccessible and yet so present that He can be possessed to the infinity that He is, an infinity I too am becoming.

If the devil is no more than a puny, death-dealing imagination—a “melancholic” one, Sisters, I should have warned you—the only way to defeat him is via the baroque kaleidoscope of a psychic space erected against the nonplace of Hell, but also against the headlong rush to the uninhabited outside, from which the soul should remain apart. Only when the plastic mobility of this interiority is in place (or rather, in motion) and unhealthy impotence is transmuted into fresh ramifications, an eternal nativity, will the world itself be available for conquests without end and interminable re-foundations. Tutti a cavallo, yes, on condition of retaining the malleable castle of the soul, laminated into degrees of love.

As Teresa travels Spain on donkey-back and in carriages, and the writer’s pen establishes her home base in a polyvalent space, the vagabond desires instigated by the devil and stirring in the soul “some passion, as happens when we suffer over worldly things [things of the age: cosas del siglo]”25 give way to another, more dominant movement. Instead of taking one’s worldly hankerings for “something great,” resulting in “serious harm” to health,26 and instead of condemning them, what matters is to put them to work. Should they become excessive, these impulses must be “fooled.” What else can we do, faced by the wiles of the malevolent genie inside us intent on preventing us from entering the interior space where the soul moves in the certainty of meeting its Other? Watch out, illusion and error are recognizable because they do harm; logically, harm cannot be anything but illusion and error in the good Being and the castle I am building to its scale!

Tears themselves are only beneficial for watering the desiccated soul when they come from God; then they will be “a great help in producing fruit. The less attention we pay to them the more there are”;27 but in tears, too, “there can be deception.”28

Fragmented and restless, forever tempted by the devil, the soul (again this third party, probingly observed as it endlessly unfurls within her) is not hopelessly in thrall to demonic falsehoods all the same. However infinite the way of perfection, union lies at the end of it—that is, at the “center,” right here, in the labyrinth of dwelling places. The writer already senses a premonitory excitement, “feelings of jubilation and a strange prayer,” an “impulse of happiness” comparable to those experienced by Saint Francis and Pedro de Alcántara, carried away by “blessed madness.”29 What could this be?

By a further twist of alert lucidity, Teresa analyzes the phenomenon as a “deep union of the faculties”; an osmosis of the intellect, memory, and will into the good Being of the Lover/Beloved. A flexible osmosis, though, since the Lord “leaves [the faculties] free that they might enjoy this joy—and the same goes for the senses—without understanding what it is.”30

And so you arrive, Teresa, with full freedom to enjoy, at the faceted jewel of your writing, which condenses your union with the Beloved and your freedom vis-à-vis Him into a cascade of metaphors-metamorphoses. Clinging proximity mixed with flighty expansiveness, brief touches, darting escapes. Centripetal and centrifugal, your jouissance is a nameless exile, a fascinating and yet appalling estrangement. What? How? Our souls cannot know. But it’s a disturbing ignorance all the same, reviving the memory of another escapade, equally both real and symbolic, which was supposed to take you and brother Rodrigo to the land of the Moors with a view to getting beheaded, thus winning martyrdom and sainthood.

In a burst of writing that soars high over the “somersaults” of the devils, you depict a soul, your soul, rushing toward the dangerous, bewitching strangeness that is so hard to express (it might sound “like gibberish” or Arabic, algarabía). It recollects itself, but without losing the élan of its euphoric activity (que aquí va todo su movimiento). At the very heart of this compacted, stony intimacy—diamond or castle—the soul is driven to making expansive proclamations.

“What I’m saying seems like gibberish, but certainly the experience takes place in this way, for the joy is so excessive the soul wouldn’t want to enjoy it alone but wants to tell everyone about it so that they might help this soul praise our Lord. All its activity is directed to this praise.”31

The journey, interior or through the outside world, is here a synonym of serenity, as prodigal sons and daughters reconcile to a world made safe at last. Revolts have been shelved, self-denials forgotten, frustrations transcended. To want to “put to work” and even pacify one’s irksome desires by the grace of loving oneself in the Other is perhaps madness, as Teresa is aware; but a blessed madness. And surely preferable to grim truth, belligerent folly, or deceptive, gloomy nihilism.

Today, as I am reading you and speaking to you, your “activity” is being widely publicized, everyone is being “told about it.” You are being rediscovered. Everybody has his or her Teresa. Tutti a cavallo. You seem to be intriguing the world all over again, beginning with me, Sylvia Leclercq, to speak only of my own headlong race.

1574. En route to Segovia, you are escorted by just four stalwarts: John of the Cross, Julián de Ávila, Isabel de Jesús (whose fine voice you discovered in Salamanca), and a layman, Antonio Gaytán: a widower whose enthusiasm for your work led him to entrust his home and daughters to a governess while he goes on the road with you. You assign to him the daunting task of spiriting fourteen nuns out of the Pastrana convent, where your fearsome friend Ana de Mendoza de la Cerda, princess of Eboli, is holding sway. Donning the habit after her husband’s death, this pretentious woman seems obsessed with aping you. The noble lady climbed into a “cloistered” carriage and took herself off to Pastrana, where she lives secluded under the name Ana de la Madre de Dios. Eaten up by envy, she has lost all proportion: everybody is to obey her, never mind the constitutions, and especially yours. The Rule is what she says it is!

Out of kindness to the unfortunate nuns left at the mercies of this capricious aristocrat—or maybe out of a desire to get even with one of your bugbears, the epitome of “artificial displays” of lordship and authority—you arrange for the fourteen sisters to be kidnapped by Julián de Ávila and Antonio Gaytán. You ought to be ashamed, Teresa, you female pícaro, you pícara of faith! After that you go ahead and make a foundation without an order from the bishop, merely with his verbal approval.

The princess turned Ana de la Madre de Dios lets you get away with it, busy preparing an exquisite revenge of her own. Have you forgotten how in 1569, when you were founding Pastrana, you gave in to her pleas and lent her the copy of the book of your Life that had just been authorized by some saintly men? Eboli left the manuscript lying around, and the servants took a peep at it. People began jeering at your visions, comparing your ecstasies to the impostures of Magdalena de la Cruz, who’d pretended to be a holy woman as well—some heretic she was! They burned her at the stake for faking, and serve her right! One-eyed Eboli has got you now. You snatched her girls, she’ll denounce you to the Inquisition!

Without the slightest inkling of these schemes, you buy a house in Segovia and move in the fourteen nuns you acquired in a less than Catholic way, perhaps, but too bad, here goes another foundation:

E E E E G E C

E E E E G E C

C G G G G G G C G G G G G

C G G G G G

E E E E G E C

E E E E G E C

John, your “little Seneca,” is lost in rapture in front of a Cross he perceives floating against the lime-washed wall of the cloister. You are writing your Meditations on the Song of Songs. The sisters all worship you, without the least discretion. It’s too good to last. Squalls and storms are about to catch up with you again.

Your confessor, Fr. Yanguas, quotes Saint Paul’s words commanding women to keep quiet in church, as a way of telling you that women should know their place; he is no fan of the alumbrados toward whom he feels you incline. The Inquisition begins to rummage through your past and scrutinize everything you ever wrote. Father Domingo Báñez is the only one with the finesse and the forcefulness to defend you—but not before making alterations here and there, and prefacing your works with a beautifully wrought screed of scholarly approval.

On the way to Avila, you can’t help stopping off at the grotto where Saint Dominic used to pray. Prostrating yourself for a long time before the saint’s apparition, you will not depart until he promises to stay by your side in your work of foundation. You are in sore need of him—but of Saint Dominic, or of Domingo Báñez?

You write: “I saw a great tempest of trials and that just as the children of Israel were persecuted by the Egyptians, so we would be persecuted; but that God would bring us through dry-shod, and our enemies would be swallowed up by the waves.”32

The Egyptians are not through with you yet, Teresa. And you, the “child of Israel,” will help whip up the tempest.

1575. Springtime at Beas de Segura, at the border of Castile and Andalusia. In the warm climate of the slopes of the Sierra Morena, almond and orange and pomegranate trees are covered in blossom. Two highborn ladies, the Godínez sisters, have donated a house worth six thousand ducats and invited La Madre to make a foundation there. The eldest, Catalina, handsome and wealthy, always refused to get married; to spite her parents, who wouldn’t hear of her going into religion, she ruined her complexion in the sun, a proper Donkey Skin. Miserable and ill, finally released by the death of her parents, she summons Teresa: the only salvation for the two orphans is a discalced convent. Saint Joseph of the Saviour at Beas thus saw the light of day on February 24, 1575. But it’s not because Beas will be a breeding-ground for saints that it stands out in Teresa’s story; it’s because this is where she meets “the man of her life.”

Such a corny cliché is not unwarranted at this point in the holy gallop. In her own words:

In 1575, during the month of April, while I was at the foundation in Beas, it happened that the Master Friar Jerome Gratian of the Mother of God came there. I had gone to confession to him at times, but I hadn’t held him in the place I had other confessors, by letting myself be completely guided by him. One day while I was eating, without any interior recollection, my soul began to be suspended and recollected in such a way that I thought some rapture was trying to come upon me; and a vision appeared with the usual quickness, like a flash of lightning.

It seemed to me our Lord Jesus Christ was next to me in the form in which He usually appears, and at His right side stood Master Gratian himself, and I at His left. The Lord took our right hands and joined them and told me He desired that I take this master to represent Him as long as I live, and that we both agree to everything because it was thus fitting.33

Teresa hesitates only for a second. Recalling her affection for other confessors, she feels guilty, attempts to rein back her desires—putting up a momentary “strong resistance,” she tells us. But twice more the Voice of the Other encourages her: there can be no mistake, her orders are “for the rest of my life, to follow Father Gratian’s opinion in everything.”34

Thunderbolt of love, amour fou, spirit made flesh. A young man of thirty, the son of a secretary of Charles V, the apostolic visitator for Andalusia, finally slakes the desire of this sixty-year-old woman. He is a son to her, obviously, but this Mother who could have been his mother is also his daughter, since he is her father confessor. Flesh and spirit at one, Teresa revels in a different ecstasy, of a kind she had never known at prayer. It resembles the paradox of the Virgin Mother as seen by Dante: “Thou Virgin Mother, daughter of thy Son,…The limit fixed of the eternal counsel” in the Paradise!35 Is this Paradise on earth, perhaps? Here is the last missing link in the chain that resorbs the immemorial incest prohibition in Teresa’s experience: the daughter of her father, who became the heavenly Father’s Bride, has now become a mother in love with her son who is at the same time her father. The fantasy of incest, purified by the theological canon, has now become embodied in earthly affects, bonds that are as real as can be.

The new water in which the ecstatic Carmelite will bathe flows precisely from this transport, in which the little girl merges with the mother. Joys of symbolic motherhood, folded into a child’s imagination; joys of infant innocence, conjugated with the omnipotence of masterly maturity. More than hysterical excitability, it is female paranoia that Mary satisfies and appeases when, from being a mother, she moves to being the daughter of her son/father, and only thus a fiancée and a wife, in the suspended time of the eternal design. Teresa does the same. She has never been so sure of herself, so triumphal in the passion of her faith: nor has she ever been as fragile, more exposed to the trials of reality, more attentive to the violent thirst of desire,36 than to the Voices of His Majesty. But the latter is bound to smile upon these new transports with a young father-brother-son-husband; there are no worries on that score.

Loving and being loved by Gratian reassures, stabilizes, and makes her feel secure, far more than did the protection of the sound and prudent Domingo Báñez. But this new connection also makes her more vulnerable than ever as she hunts for new, efficacious “fatherhoods,” both spiritual (angling for the support of the great Dominican writer Luis de Granada, she writes him a markedly humble letter on the advice of their mutual friend Teutonio de Braganza) and institutional (she doesn’t shrink from appealing to Philip II for help when her darling Eliseus—one of Gratian’s many code names—gets into trouble).

Your passion for Jerome Gratian, infantile and pragmatic at once, cannot be compared—although some have done so—to the vaporous swoons of Madame Guyon’s “pure love” for Fénelon. The more in love you are with your cherished son-father—at last, an hombre of flesh and blood by your side, a physical replica of the Lord, would you have settled for less?—the more realistic, militant, astute, and active you become, a businesswoman all over. Besides, for all that you may be the “daughter” of your son-father-partner, you are the boss in this couple, my headstrong Teresa, from the start, and increasingly as you pursue those business affairs at your usual furious pace:

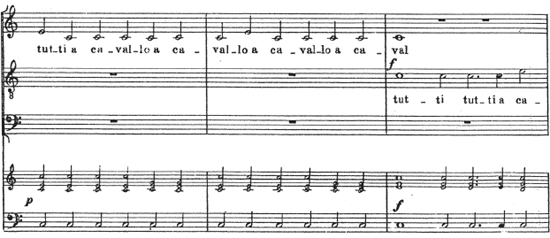

tut-ti tut-ti a cavallo

tut-ti tut-ti a cavallo

tut-ti a cavallo a cavallo a cavallo a cavallo a cavallo a caval

tut-ti tut-ti a cavallo

tut-ti tut-ti a cavallo

I try to keep up with that pace, I pant and struggle, unlike you. I count with you the foundations you continue to make until your last breath, always against the backdrop of your love for Gratian, naturally, as he “replaces” the Lord: “Y díjome que éste quería tomase en su lugar mientras viviese”! Isn’t that something? Have you thought about what such a replacement could possibly mean? No? Is it that you don’t do much thinking anymore, carried away by your passion for that man? Of course not, that’s not it at all. Actually the intoxication doesn’t last long, you soon perceive the limits of the man and of the thing, but you cling to the game, believing without completely believing in it; we’ll take a closer look at this later, you and me. For the moment let me ride with you, come on, everyone to horse:

E E E E G E C

E E E E G E C

C G G G G G G C G G G G G

C G G G G G

E E E E G E C

E E E E G E C

So your Eliseus wants you to found a house in Seville? Seville it is! In fact, by this move the apostolic visitator Jerome Gratian of the Mother of God was disobeying—again!—the general prior of the Carmelite order, Juan Bautista Rubeo. A tricky predicament that soon proved untenable when Gratian found himself trapped between the pincers of Philip II’s wish to accelerate the Teresian reform and the obduracy of the order, reluctant to be reformed. You use your Pablo-Eliseus-Paul and he uses you, bestowing little pet names like Laurencia or Angela…All in the cause of reform, as we have said, but one can’t dig in the spurs without incensing the laggards and drawing persecution down. The next five years will be a perfect tempest of trials and thunderbolts.

Seville is a long way from Avila, and Andalusia is a sly country; it scares you. The local churchmen don’t even respect the authority of the general, Fr. Rubeo: they actually condemned a disciple of Juan de Ávila to burn at the stake! No matter, you are at the height of your fusion with Gratian, you pledge him your “total obedience” for “as long as you live,” and you hurtle on, keener than ever.

Father Ambrosio Mariano lends a hand, but he gets ahead of himself: he persuades you that Archbishop Cristóbal de Rojas has given his permission, when he has done no such thing. Worse, Mariano thinks nothing of leaving you all by yourself in Seville in a frightful situation: comprehensive hostility to discalcement and not a cent in donations! Those giddy Sevilleans only care about having fun. It’s a port city, where whores count more than nuns, but this trite pleasantry doesn’t make you laugh. The things you learn, on the road! The calced community are outraged, your program is seen as meddling, as “interference”! But you get your way: on May 29, 1575, a convent for discalced nuns is founded in Seville, once more under the patronage of Saint Joseph.

How happy it makes you! New novices, charming Andalusian girls, join up. They intrigue you, too: the confirmed Madre fundadora starts to explore a new country, the landscape of the female soul. The text of the Foundations begins to sound as though the chronicle of your works were also, or chiefly, the novel of these sorely tested and often castigated lives. Take the chapter on Beatriz de Chávez, aka Beatriz de la Madre de Dios, the spiritual daughter of your dear Eliseus. What a handful, that girl! You try to understand her, in writing. We’ll come back to it at the end of our ride.

One thing has never been plainer than it is here, in Seville: the world threatens to gag you, Teresa, my love, it may end up by burning you alive. What do you expect when you move from pure ecstasy to the work of founding, when you aspire to found pure ecstasy in the world, against the world, but with the world? Tensions between the women are rising, too; nothing new about that, but it’s getting more dangerous. Your own niece, María Bautista, feels licensed to disobey you and speak ill of you, she even finds fault with Gratian. She receives a wrathful letter from you, dated August 28, 1575;37 but will this tongue-lashing suffice to bring her to heel?

It gets worse. Copies of the Life are circulating, the princess of Eboli has filed a complaint against you, and the book is submitted to the court of the Inquisition; even Fr. Báñez is growing peevish. And María Bautista makes a point of seeing the influential Dominican every day—emphatically not for your or Gratian’s benefit.

But Domingo Báñez is an honest man in the end, thanks be to God. He rescues your book in exchange for a modicum of censorship, emendations which of course you accept. It’s better than being burned. You’ve won, but be prudent!

Another piece of good news: your brother Lorenzo is back from Peru with a fortune, money that will help reflate the beggarly convent in Seville. He will be “consigned” for his pains, since your enemies are alert, they will do anything to sabotage you; it’s lucky they didn’t put La Madre’s brother behind bars! This pitiful imbroglio does not stop you giving him a good telling-off. It is ridiculous, nay, unacceptable, to call oneself “don” on grounds of one’s fiefdoms in Indian country! Now that you are sure of yourself and of him, there’s no need to be flattering him with titles. You can dress him down as he deserves, beginning with the matter of honra, the good old family vice. Well, you had bones to pick with the new and fervently discalced brother, and you like being the only captain on board; family take note: you’ll make foundations as you see fit!

This claim to autonomy doesn’t stop you requisitioning Lorenzo’s nine-year-old daughter, Teresita, for the convent. Gratian is against it; but she won’t take vows just yet, of course, you only want her for “her education.” And also to spread a little merriment in halls that often lack it, truth to tell. You established asceticism for it to be sublimated in joy, Teresa, you established joy to be elucidated by asceticism; Teresita will be your great weapon in this debate, because the little one is an “imp” and highly “entertaining.” People should know that Teresa de Jesús’s holy houses are not disdained by merry little imps, quite the contrary.

Meanwhile the persecutions continue, and it’s your job to face up to them, to think of everything, to tie down everything that can be, and when the storms blow too hard, simply to hang on. Gratian helps out, but not always, and not really. You already know how impulsive he is, always too harsh or too lenient, clumsy with some people and ingratiating with others: “Difficulties rain down on him like hail.”

Now for the latest dirty trick: Gratian is packed off to a monastery of the Observation. How appalling, he must be rescued, I’ll write letters, pull every string I can…Right, it’s over, he’s back. But in early 1575, the general chapter of the order at Plasencia resolves to dismantle the convents Gratian founded in Andalusia without permission from Fr. Rubeo. And again it falls to Teresa to intervene. She writes to the general of the order, Rubeo, pleading for his continued support.

December 1575. An anonymous Carmelite nun denounces Teresa to the Inquisition. “And nonsense also was what she said of us, that we tied the hands and feet of the nuns and flogged them—would to God all the accusations had been of that sort.”38

But it’s the last straw for Provincial Ángel de Salazar. Finally out of patience, he commands Teresa to repair to a convent in Castile: “[He] said that I was an apostate and excommunicated.” It seems the bell is tolling for Teresa’s enterprise.

Searches, interrogations; are you about to be arrested, Madre? A vehicle belonging to the Inquisition is stationed before the door of your convent in Seville. But only a deposition is required, which you will send to the Jesuit Rodrigo Álvarez, the acknowledged expert in matters of delusion and error.

But you, skillful Teresa, not only bewitch your world with the grace of a writing that thrills us today, four centuries after the tempest; you also carry out a veritable plan of military encirclement! First, you present a long list of ecclesiastics prepared to testify to your good faith: Fr. Araoz, the Jesuit commissary; Fr. Francisco de Borja, the former duke of Gandía; and numerous others. Then comes the epistolary race, the gallop of letters:

tut-ti tut-ti a cavallo

tut-ti tut-ti a cavallo

tut-ti a cavallo a cavallo a cavallo a cavallo a cavallo a caval

tut-ti tut-ti a cavallo

tut-ti tut-ti a cavallo

Humbly you confess your penchant for mental prayer in the wake of Pedro de Alcántara and Juan de Ávila, well aware that that’s your major transgression in the eyes of the authorities. You swiftly move on to reference the many illustrious scholars who helped you protect yourself from this unconscionable error, Dominicans this time, necessarily; chief among them the councilor of the Holy Office at Valladolid, the ubiquitous Domingo Báñez.

But don’t expect to get out of trouble so easily. The investigation has only just begun. You are summoned again—to justify your ecstasies! Kindly provide a new deposition!

You’re enjoying this gallop of writing, after the race of the roads. Here’s how you sum up that phase of the adventure in a missive to María Bautista, on February 19, 1576: “Jesus be with you, daughter. I wanted to be in a more restful state when writing to you. For all that I have just read and written amazes me in that I was able to do it, and so I’ve decided to be brief. Please God I can be.”39

Of course, it pleases Him to fulfill your every wish. His Majesty is hand in glove with you, His Voice speaks through your lips, as you don’t fail to remind us. And you’re capable of convincing anyone who takes the time to listen. Indeed, the wind is momentarily turning to your advantage. How could even the wind resist your galloping?

A new house is purchased, the recalcitrant Franciscans eventually come around, they didn’t want you in the neighborhood, poor things, and now they do.

Teresa is triumphant. She leaves Seville, where María de San José takes over as prioress. Before departing she sits for Fr. Mariano’s painter friend, Giovanni Narducci, now Juan de la Miseria. Writing to Mariano on May 9, 1576, she sounds elated, hopping gaily from one topic to the next, as if the Sevillean ordeal had been nothing but fun and games, a period of ebullient agitation:

The house is such that the sisters never cease thanking God. May He be blessed for everything.…This is not the time to be making visitations, for [the friars] are very agitated.…Oh, the lies they circulate down here! It’s enough to make you faint.…Nonetheless I fear these things from Rome, for I remember the past, even though I do not think they will be to our harm but to our advantage.…We are receiving many compliments and the neighbors are jubilant. I would like to see our discalced affairs brought to a conclusion, for after all the Lord won’t put up with those other friars much longer; so many misfortunes will have to have an ending.40

Prior to departure, after kneeling before the archbishop to be blessed, Teresa cannot believe her eyes and ears when the same archbishop, don Cristóbal de Rojas, the source of so many vexations, kneels in turn before her and asks for her blessing. It is June 3, 1576.

1576–1577. Enjoying the mild climate of Toledo, housed in a pleasant cell, you receive from Lorenzo the manuscript of the Foundations you had left at Saint Joseph’s and continue composing your text. The updates concern Gratian, the calced and the discalced, your idea of creating a special province of the Carmelite order with Gratian as the provincial, a project you already mooted in your letter to Philip II. Separately you draw out the political lessons of past experience, from the Incarnation to Seville. Firstly, it is important to consolidate the temporal sphere by a “government” that is temperate and yet clearly hierarchical, in order to advance the spiritual good: “It seems an inappropriate thing to begin with temporal matters. Yet I think that these are most important for the promotion of the spiritual good.”41

Respect for hierarchy is essential from your point of view as foundress, especially among women who are duty-bound to acknowledge their chief, that is, yourself:

I don’t believe there is anything in the world that harms a visitator as much as does being unfeared and allowing subjects to deal with him as an equal. This is true especially in the case of women. Once they know the visitator is so soft that he will pass over their faults and change his mind so as not to sadden them, he will have great difficulty in governing them.42

Is that because obedience is harder for a woman? For a woman like you?

“I confess, first of all, my imperfect obedience at the outset of this writing. Even though I desire the virtue of obedience more than anything else, beginning this work has been the greatest mortification for me, and I have felt a strong repugnance toward doing so.”43

Be this as it may, the works are multiplying. You maintain a prolific correspondence (200 letters up to 1580), dispense advice of all sorts, circulate The Way of Perfection and keep an eye on its reception. In 1577 you begin The Interior Castle—a metapsychology avant la lettre, the quintessence of your journey toward the Spouse and ultimate nuptials with Him. Nothing is left to chance, and all these works are created while managing in hands-on fashion the establishment and staff of twelve nunneries, without neglecting the affairs of the male counterparts founded in accordance with your new-old Rule.

You have the gift of asserting your authority without dispelling good cheer, your own or that of others. Witness that sparkling vejamen, also from 1577—a response known as the Satirical Critique, mixing faux pedantry with schoolboy humor, to a solemn colloquium held in your absence in the parlor at Saint Joseph’s in Avila. You had requested Julián de Ávila, Francisco de Salcedo, John of the Cross, and your brother Lorenzo de Cepeda to reflect on those words the Lord once spoke to you, “Seek yourself in Me.” Once the bishop who was also present had arranged for the various speeches to be sent to you in Toledo, you replied with the jovial irony of one who had just escaped the clutches of the Holy Office: “I ask God to give me the grace not to say anything that might merit being denounced to the Inquisition.”44 And you then proceeded to mercilessly tease each of your friends for their contributions; we shall reread these remarks once you have passed away.

I have a notion that the months from July 1576 to December 1577 constitute the most luminous period of your later life. You are given over to writing, elucidating, and transmitting. You don’t have much longer to live, but for the present, time has ripened: you experience it fully, soberly, and laughingly.

The papal nuncio who championed your reforms, Nicolás Ormaneto, has died. You leave for Saint Joseph in Avila; could it turn out to be a definitive “prison”? Your fevered race repudiates such a thought. Let’s wait and see.

The new nuncio, Felipe Sega, bishop of Piacenza, loathes the discalced movement and brands you a “vagabond and a rebel.” Accusations rain down once more on Gratian, relating to his licentious ways with women. That’s the situation, and nothing’s going to change: Gratian needs your protection more than you need his presence or his affection. Another letter to His Royal Majesty is called for. You write and sign it on December 13, 1577.

All is not well at the Incarnation, either. On the order of Gerónimo Tostado, vicar-general of the Carmelites in Spain, the calced provincial Juan Gutiérrez de la Magdalena arrives to preside over the election for prioress. He threatens to excommunicate anyone who votes for you.

Such is the frayed atmosphere in which you continue exploring the Dwelling Places of The Interior Castle, that masterpiece of introspective analysis. Yet the work is completed on November 29, 1577, in less than six months. However did you do it, Teresa?

“Hosts of demons have joined against the discalced friars and nuns,” you complain to your friend Gaspar de Salazar on December 7.45 Matters reach such a pass that John of the Cross and a close associate, Germán de San Matías, are taken captive by Gutiérrez. Where to turn, when the general of the order and the nuncio are both ranged against you? To your pen, Madre!

For the fourth time you write to Philip II, outlining the conflict between the two rules and pleading on behalf of John of the Cross, for “this one friar who is so great a servant of God is so weak from all he has suffered that I fear for his life. I beg Your Majesty for the love of our Lord to issue orders for them to set him free at once and that these poor discalced friars not be subjected to so much suffering by the friars of the cloth.”46

Absorbed in founding, in writing, in Gratian, have you not rather neglected your “little Seneca”? Is he too ascetic for you, too saintly in his inhuman self-mortification, too inaccessible in his elliptical purity? Are you feeling guilty, Teresa? It’s time to make amends! Between you and me, John deserves salvation more than Gratian. But you’ll save both of them, my future Saint Teresa.

Christmas Eve, 1577. Teresa falls down the stairs and breaks her arm. The traveler is getting old. Her morale is as solid as ever, but her bones are getting brittle.

Don Teutonio de Braganza, appointed to the archbishopric of Evora in Portugal, who was a Jesuit from 1549 to 1554 and knew Loyola in Rome, asks you to make a foundation in his city. Alas, it’s impossible. Your reforms are under threat in Spain, and there’s still many a road to be galloped down in your native country; it’s no time to be going abroad. But can his lordship do something for Gratian, perhaps, and for John of the Cross? The latter “is considered a saint by everyone…In my opinion, he is a gem.”47

Her arm in a sling, the aging Teresa can still write. A deluge of diplomacy, of piety, of courage and craftiness will come to drench everyone who has the honor of knowing her, closely or from afar.