Nor did You, Lord, when You walked in the world, despise women.

Teresa of Avila, The Way of Perfection

They are very womanish…[be] like strong men.

Teresa of Avila, The Way of Perfection

LA MADRE, on her deathbed, watched over by:

ANA DE SAN BARTOLOMÉ and TERESITA, La Madre’s niece, Lorenzo’s daughter, TERESA DE JESÚS in religion; with them are

CATALINA DE LA CONCEPCIÓN

CATARINA BAUTISTA

Followed by entrance of:

BEATRIZ DÁVILA Y AHUMADA, Teresa of Avila’s mother

CATALINA DEL PESO Y HENAO, the first wife of Teresa of Avila’s father, Alonso Sánchez de Cepeda

Characters passing through, in alphabetical order:

ANA DE LA CERDA DE MENDOZA, Princess of Eboli

ANA DE LOBRERA, ANA DE JESÚS in religion

ANA GUTIÉRREZ

ANA DE LA FUERTÍSIMA TRINIDAD

PADRE ANTONIO DE JESÚS

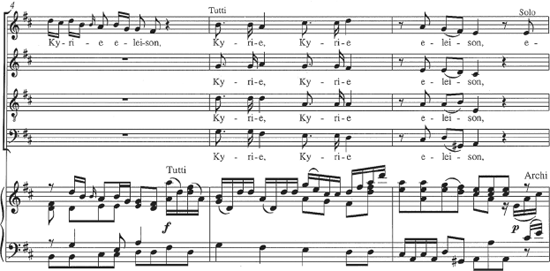

The image of the Virgin that Teresa always kept with her. Private collection.

BEATRIZ DE JESÚS, a niece of La Madre

BEATRIZ CHÁVEZ, BEATRIZ DE LA MADRE DE DIOS in religion

BEATRIZ DE OÑEZ, BEATRIZ DE LA ENCARNACIÓN in religion

CASILDA DE PADILLA, CASILDA DE LA CONCEPCIÓN in religion

CATALINA DE CARDONA

ISABEL DE JESÚS

PRINCESS JUANA, sister of Philip II

JUANA DEL ESPÍRITU SANTO, prioress at Alba de Tormes

JERÓNIMA GUIOMAR DE ULLOA

LUISA DE LA CERDA

MARÍA DE OCAMPO, MARÍA BAUTISTA in religion

MARÍA DE JESÚS

MARÍA ENRÍQUEZ DE TOLEDO, Duchess of Alba

MARÍA SALAZAR DE SAN JOSÉ, prioress at Seville

EMPRESS MARIA THERESA of Austria

TERESA DE LAYZ

AN ANONYMOUS NUN

With the portrait of the Virgin Mary bequeathed to Teresa by her mother, whose blue veil casts its iridescence over the deathbed scene.

LA MADRE

TERESITA

ANA DE SAN BARTOLOMÉ

JERÓNIMA GUIOMAR DE ULLOA

LUISA DE LA CERDA

ANA DE JESÚS

and CATALINA DE LA CONCEPCIÓN, CATARINA BAUTISTA

Although La Madre had wished to go up to Heaven in a flash, her niece Teresita will testify that her death was neither easy nor quick. And yet Teresa is not distressed at entering into her final agony. The twilight of her awareness fills her with blue-tinted voluptuousness, blue as the wintry dawn over Avila, blue as the Virgin’s cloak in the picture her mother bequeathed to her before she died.

She knows she’s not alone. Ana de San Bartolomé, the young conversa nun who is nursing her, and Teresita—now in the bloom of her sixteen years—keep watch with tender solicitude by her bedside, accompanied by Catalina de la Concepción and Catarina Bautista. Sounds of padding footsteps, rustling habits, murmuring voices; scents of skin, clean towels, cool or warm water. The dying woman cannot see the faithful companions by her side, but they inhabit her visions.

Is it possible to die, when she is already dead to the world so as to live more completely in God? Teresa thinks death is delightful, an “uprooting of the soul from all the operations it can have while being in the body”; because the soul was already, while the body lived, “separated from the body” in order to “dwell more perfectly in God.” Often, as during those terrible epileptic comas, the separation of body and soul was such that she didn’t “even know if [the body] had life enough to breathe.” Soon, now, it will not. The rest is unknown, something even more fearsome and delightful, since she loves. “If it does love, it doesn’t understand how or what it is it loves or what it would want.”1 The unknown is love. Teresa never stopped wondering about love, and writing about it. There’s no reason to stop now.

The blue Virgin has her hands crossed over her breast, and the face of Beatriz Dávila y Ahumada. With the folds of her azure robe she protects the fortress of Avila, but the Mother of God does not say a word to the dying woman. How long ago did this “mother without flaw” abandon her daughter? Some fifty years?

Teresa sees one of her own texts materialize on the pale silk. To write about the inner life means spewing out “many superfluous and even foolish things in order to say something that’s right.” It required a lot of patience for her to write about what she didn’t know. Yes, sometimes she’d pick up her pen like a simpleton who couldn’t think of what to say or where to start.2 It required patience to get people to read her, and then to reread herself. Torrents of engraved words, funerary columns, whole pages stamped into the translucent walls of the interior castle, which Teresa can retrieve with no help from the “faculties”—whether understanding, memory, or will—it’s just there, just like that. “Hacer esta ficción para darlo a entender”:3 literally, to “make this fiction to get my point across.” “Hagamos cuenta, para entenderlo mejor, que vemos dos fuentes”:4 “Let’s consider, for a better understanding, that we see two founts.” Let’s pretend, pretend to see. Let’s tell stories. Let’s write them down.

TERESA. Converse with God. What else could I do, being a woman and a conversa? (Lengthy pause.) My Lord and Spouse! The longed-for hour has come! It is high time we saw each other, my Beloved, my Lord! (Listening.) Conversar con Dios. Such things can’t be explained except by using comparisons. To grasp them, one must have experienced them.5 (In a rush.) A conversa who wants the world to be saved…with my daughters…After the return of Fr. Alonso de Maldonado from the Indies…Who’d have thought it?…I have been out of my mind…I’m still delirious…the Lord says that I must look after what is His, and not worry about anything that can happen…6 (Quick smile.) The long-awaited time has come!

(Long pause.)

A new page imprints itself upon the Virgin’s blue cloak outstretched over the ramparts of Avila, a page La Madre wrote regarding another Beatriz, a relative of Casilda de Padilla. She’d never met Beatriz de Óñez, or Beatriz de la Encarnación, but had heard much about her God-given virtues from the awed sisters at Valladolid. This was one daughter that Teresa was going to take with her when she flew away from the Seventh Dwelling Places toward the Lord.

TERESA, in a tone of fervid reminiscence. Beatriz, daughter, woman without flaw…Mother…pray God to send me many trials, with this I’ll be content…

As she mutters to herself in this vein, pious Ana de San Bartolomé recognizes the words La Madre had written in a section of the Foundations, glorifying the nun whose “life was one of high perfection, and her death was of a kind that makes it fitting for us to remember her.”7

TERESA, feverishly. Have you asked the monastery nuns? Did they ever see anything but evidence of the highest perfection? High perfection is an interior space free of all created things, a disencumbered emptiness, a purified soul and God divested of all character, dispossessed of Himself, turned in on Himself.

TERESITA, in tears. She’s dreaming…as if reciting something…

TERESA. “She was next afflicted with an intestinal abscess causing the severest suffering. The patience the Lord had placed in her soul was indeed necessary in order for her to endure it.” Just like my mother. It was wonderful to behold the perfect order that prevailed internally and externally, in every way…

But wasn’t her muddled mind confusing Beatriz de Óñez with the nun who had cancer, the one she had cared for when a novice at the Incarnation? Or perhaps with Beatriz Dávila, the mother Teresa pitied as well as honored, but assuredly praised to the skies? She wanted to follow in her footsteps to the Beyond, but by choosing another way of perfection: the monastic way.

ANA DE SAN BARTOLOMÉ, to TERESITA, interrupting her prayers for a moment. She’s calling on her mother for help before going to join the Lord.

TERESITA. Do you think so? I think she’s seeing her mother in the Lord. She wants to find peace in her lap, to know herself to be perfect, in her and like her.

Teresita surrenders to emotion: for the foundress, her little Teresica, as she called her, was always the impish nine-year-old she welcomed into the Discalced Carmel at Valladolid. Even so, the little one is often more insightful than other sisters about the extremes of mind and body, as she has just demonstrated.

La Madre can barely hear them. Immersed in visions, she continues to murmur the text unfurling across the blue robes of the Virgin above the walls of Avila. Nothing but her text, chiseled into what is left of her body and soul, the second nature etched into her by writing. It takes up all the space of her dwelling places, the whole castle.

LA MADRE, reading. “In matters concerning mortification she was persistent. She avoided what afforded her recreation, but unless one were watching closely, this would not be known. It didn’t seem she lived or conversed with creatures, so little did she care about anything. She was always composed, so much so that once a Sister said to her that she seemed like one of those persons of nobility so proud that they would rather die from hunger than let anyone outside know about it.”8 (Pause.)

Who is speaking? Who speaks through my lips? I know you’re near, daughters, even if I can’t see you with my bodily eyes. I am not yet dead, so there’s no need to weep or to rejoice, it comes to the same thing. I’m thinking, that’s all, dying people do that, didn’t you know? (Pause.) In fact, the approach of death is the best time for the strange activity of thinking by writing. I think, therefore I am mortal; I question myself, I wonder what right I have to see the Beloved face to face. (With fervent reminiscence.) That sister who was talking through my lips, who is she? Or was it me thinking aloud, a witness to my mother’s distress? Me, wrapped in the suffering of Beatriz de la Encarnación?

Although Teresa’s brain is growing feebler, she keeps qualifying everything she says, as she always used to. The coming end merely adds leisure to her lucidity. One can’t approach God with trepidation, one can’t serve Him in despondence.

LA MADRE, reading. “The highest perfection obviously does not consist in interior delights or in great raptures or in visions or in the spirit of prophecy, but in having our will so matched with God’s that there is nothing we know He wills that we don’t want with all our desire; and in accepting the bitter as happily as the sweet, when we know that His Majesty desires it.”9

ANA DE SAN BARTOLOMÉ, repeating in simplified form the lessons Teresa has imparted, as she follows the murmuring voice. Now she’s talking about honor, she’s against it, she can’t bear all those people scrambling after it.

TERESITA. At home, she used to accuse my father Lorenzo of doing that. But the honor of Grandma Beatriz, I mean, her flawlessness…I’m confused…

Teresita isn’t sure whether she is supposed to revere the perfection of her grandmother or seek other, happier models. But still, Beatriz Dávila couldn’t have been all gloom, however miserable her life, since La Madre’s mother used to read novels of chivalry, apparently. Fancy that! I’ve also heard that when she was young, Auntie Teresa would get the giggles playing chess!

The dying woman has turned the page. For fifty-five years now, the magic of Beatriz Dávila y Ahumada has been diffracted into a long procession of women who are now filing past one by one, under the closed eyelids of the traveler on her last journey toward the Spouse. They move through Avila’s narrow streets, climb the towers, pop in and out through the gates. The philosopher Dominique de Courcelles, who was no more present than I was at the final days of the future saint, has had the same insight as myself, Sylvia Leclercq, regarding the lifelong hold of the maternal magnet upon Teresa and the powerful way it was projected on her daughters. When La Madre was busy with her foundations she was also exploring the secrets of this relationship, repeatedly testing the proximity she cultivated to her progenitor, as well as the distance she kept from her.

Her “sisters” and “daughters” were not all natives of Avila, except perhaps for María Briceño, teacher of the young lay students at Our Lady of Grace, and Juana Suárez, the dear childhood friend who led the way to the Carmelites; but the nearness of death makes her gather them all together, loved or hated, all of them without exception, in Avila. Time regained unfolds in maternal space.

Doña Jerónima Guiomar de Ulloa opens the procession, dressed alternately in a gold-spun gown and in rags, the way she was on the day she took the veil.

TERESA. Was I mistaken to write that women are more gifted than men at taking the path of perfection?10 On the whole they are…with some exceptions. I like exceptions. Doña Jerónima, you turned your palace into a convent, and you were the first to donate your fortune to sustain the Work. I can never thank you enough, O Lord God, for allowing me to meet this highborn widow, wedded to prayer, who was closely in touch with so many Jesuit fathers…(Gazes at her for a while. Pause.)

We really became good friends when you directed me to your confessor, Fr. Prádanos.11 (Doña Jerónima blushes at the memory.)

(Teresa’s lips, mumbling inaudibly.)

You knew my needs, you witnessed my sorrows, and comforted me. Blessed with a strong faith, you couldn’t help recognizing the doings of God where most people only saw the devil. (Moving lips.)

DOÑA JERÓNIMA, as a loyal disciple. And where even men of learning were baffled, let me remind you.

TERESA. At your home, and in the churches you know, I had the chance to converse with Pedro de Alcántara…(Lips.)

(Smiling.) I must confess, I had something to do with the favors the Lord was pleased to grant you. And I received by that means some counsel of great profit for my soul.12

Doña Jerónima Guiomar de Ulloa goes on her way, all absorbed in her own soul.

Doña Luisa de la Cerda is next in line. Long ago she lavished on Teresa her endearing madness and her jewels; she shared, after all, some of La Madre’s passions and frailties. She too was on excellent terms with some influential prelates, such as Alonso Velázquez who was instrumental for the foundation of the Carmel at Soria. The dying nun is content to smile at this ghost. Her strongest linked memory is the sense of triumph that buoyed the granddaughter of the converso Juan Sánchez in the great city of Toledo: while she was staying, that time, in the opulent palace of Luisa de la Cerda, a violent transport lifted Teresa toward the dove flying over her head. It was quite different from earthly birds—the dove of the Holy Spirit, soaring aloft for the space of an Ave Maria. That jouissance was followed by a deep sense of rest, like the grace accorded to Saint Joseph of Avila himself in the hermitage at Nazareth.

DOÑA LUISA, anxious, dreamy. Will I ever see it again?

TERESA. As I saw it in the city of my ancestors?

Yes, there is the dove again, flying away after Luisa de la Cerda.

Ana de San Bartolomé can only make out murmurs, stray words here and there, she can only follow in prayer: so she invents La Madre’s reverie.13 She imagines it, just like I, Sylvia Leclercq, am doing.

TERESA. And you, dearest Ana, my faithful little conversa…my sweet and unassuming secretary, companion, nurse…You were illiterate when you arrived, and you learned to read and write by copying my hand. Oh yes, I know how strong you are: didn’t you fend off your first suitor by covering your head with a dishcloth? (Leaning back.) I can see it from here, you will be sent to found the Carmel at Pontoise in France, where you will be prioress, yes, absolutely, I can see it all, no use shaking your head. Go and rest awhile, go on, Teresita can look after me very well. You can see that I’m better, God doesn’t want me yet…Run along! Who’s this I see coming now?

ANA DE SAN BARTOLOMÉ, hopelessly shy, walks on tiptoes, talks in a whisper. It looks like one of your nieces, Madre…

TERESA. Come forward, then, niece—no, not you, Teresita. It’s Beatriz de Jesús, visiting just in time…You will be appointed under-prioress at Salamanca, my dear. Don’t goggle your eyes at me, I know it, that’s all…You have a lot of nerve, and more importantly the pluck to retort to the pamphlet that Quevedo will circulate against me…My being canonized by Gregory XV, he’ll not begrudge me that, but to be anointed “patroness of all the kingdoms of Spain,” that’s going too far! The great satirical poet prefers the Moor-Slayer…of course, a warrior saint like the apostle James, our Santiago Matamoros, whose help was so invaluable during the Reconquista, cuts a finer swagger than a mousy nun who wasn’t even a letrada! As for the Marranos…no, let’s drop it. Well then, you, Beatriz, will stand up for me, yes you will…Though we saints obviously don’t need that kind of accolade. His Majesty is enough for us, as I have often said…it’s a futile quarrel…You won’t call it a stupid one, but that’s what you’ll be thinking. What a lamentable affair. In the end, Quevedo or no Quevedo, the pope approves the court’s decision…the all-powerful minister, Olivares, was rather fond of me…So were you, dear child…Be like strong men, my daughters! (Smiles.) You understand me.

The silence is suddenly torn by the sound of a woman singing and clapping her hands, Andalusia-style.

TERESA. What a surprise! Who can this be, singing and dancing like myself in younger days?

The voice approaches, to reveal the face of Ana de Jesús.

TERESA. So it’s Ana de Lobera! (Falling into excited reminiscence.) Of course! Come closer, my child! You’ve always been different, Ana de Jesús. A queen among women, go on, don’t look so innocent, you knew you were, in spite of your genuine and heartfelt humility, which I don’t deny! You were the most attractive of all. Yes, plenty of people thought so—my little Seneca, for instance, not to use his real name. (In a jaunty tone.) There are great beauties among the nuns, you know. I have my own views on this. I’ve urged you often enough: be of good cheer, sisters!14 You will all be beautiful and queenly, worthy of the Lord, or almost…For you have to learn how to be cheerful while coming to me “to die for Christ, not to live comfortably for Christ.”15

So it is you, Ana de Jesús! Come nearer, come on, I can see you with the eyes of my dear Seneca! (Lips.) The best of prioresses, who directs Beas like a seraphim—it was John of the Cross who said that. Approach, child. After I am dead, you will gather all the manuscripts left by the Holy Mother you’ll remember me as, and hand them to fray Luis de León for publication. It’s not that I’m particularly concerned with my writings, as you know I hardly ever reread my work. But The Way of Perfection must, please, remain in the form that I have given it. The rest I leave up to you, do the best you can…You and Fr. Gratian will take care of printing the Foundations that our Lord commanded me to set down in writing…in Malagón, but when was it, exactly? The command Fr. Ripaldo finally asked me to carry out, much later, in…I’m not sure…Salamanca…(Staring fixedly at Ana.)

ANA DE JESÚS. I’ll be reproached for supporting Fr. Gratian, Mother. It’s already earned me the hostility of Nicolo Doria.

TERESA. His fury, to be accurate. You’ll get three years’ reclusion, that’s all, a trifle for an inspirational muse like you. And eternity into the bargain! Not just in the heart of John of the Cross! And fray Luis de León will compose his Exposition of the Book of Job especially for you.

ANA DE JESÚS. You flatter me, Holy Mother.

TERESA. Not a bit of it. And since you find me so holy, hear this prediction: You will introduce the Discalced Carmelite order into France, with the help of little Ana de San Bartolomé who’s kneeling right there. She will be of great service. But we’ll leave that to Madame Acarie, at Bérulle…And you’ll go to Paris, and to Dijon, and maybe even to Brussels and the Netherlands…(Pause.)

TERESITA, bending low over the pallid face. What was that you said about John of the Cross, Mother?

Ana de Jésus. Sixteenth century. Carmel of Seville. Private collection.

Teresita and Ana de San Bartolomé are avidly drinking in the murmured words; the old lady’s life-breath seems in no hurry to desert her. She smiles at her visions, tongue in a knot and throat coughing up blood, making it hard to articulate. Her words must be guessed at, they guess, they love her. She turns toward the two nuns.

TERESA. John met her in 1570, you see, when she was just a novice. When he came out of the dungeons in Toledo in 1578 he dedicated his Spiritual Canticle to her, the poem she’d asked him to write as well as the commentary on it. I haven’t been able to read it, unlike the other texts.…I tell you again, Ana de Jesús has the works, I only have the noise…(Pause.)

La Madre’s lapidary way with words stays with her to the end, whether for laughter or tears. The two nurses stroke her forehead and wipe her lips with a cold cloth. They are not sure what would be most restful for Teresa of Jesus; should they talk or keep quiet? She was never like other people. Why would she conform now?

As she prepares to depart, she finds it sweet to remember the kind, the gentle, the maternal ones. There was Ana Gutiérrez, remember, who cut her hair one day when Teresa became overheated in an ecstasy. The girl thought the hair wonderfully soft and honey-scented.

LA MADRE, curtly. Stop that at once! Throw the hair on the nettle patch!

Exeunt the sainted strands, Teresa remembers it well. Alas, it was just the beginning.

TERESA. To think they’re going to chop me into relics, dear Ana, and you’ll all stand back and let them! I suppose it could be a fashion, one of those inevitable human foibles…No, if the Lord tolerates these macabre orgies, even among my friends, it can only be because I’ve sinned.

She shakes with laughter on her narrow cot. The sisters glance sidelong at each other: Is she losing her mind? “No, never, not a saint like Teresa of Jesus!”

TERESA. María de Jesús Yepes, she was something else, awfully manly! (Wrinkling nose.) The pope said that about her. Not quite my type, that lady, but don’t forget she helped me draft the Constitutions.

(She lifts her head, tired eyes sparkling with mischief.)

Do you know what would give me pleasure, girls? (Speaking fast.) Bring me Isabel de Jesús, she could sing me a villancico in her crystalline voice. Or better not, leave it, it’s too late at night—not even Princess Juana, the king’s sister, could get her to come around at this time. Why did Her Royal Highness come to mind just now? She wanted to imitate me, that’s right, I seemed awfully simple for a saint! It was too great an honor for me. And not simple enough for her, as it turned out. One must turn things inside out in order to grasp what’s really going on in someone’s head, especially a woman’s…She was a great help, the lovely Isabel, I mean. So was Princess Juana.

Teresa straightens up suddenly. Those two girls mustn’t think the foundress is in any hurry to meet her Spouse! And the faithful pair rejoices at the improvement.

TERESITA. A sip of water, Mother?

TERESA. Why not? God keep you, darlings. I’m not thinking of water just now. I’ve drunk too much, said too much…“Just being a woman is enough to have my wings fall off—how much more being both a woman and wretched as well”!16 No matter, a person’s soul, male or female, is nothing but an abject pile of dung, and only the Divine Gardener can change it into a fragrant bank of flowers. And even then He needs a great deal of help! You look frightened, you two. What are you afraid of? That I might die? Or of what I say? (Knowing smile.)

TERESITA and ANA lower their eyes and kiss her hands.

TERESA. “We women are not so easy to get to know!” Women themselves lack the self-knowledge to express their faults clearly. “And the confessors judge by what they are told,” by what we tell them!17 (Broad grin.)

Racked once more by a dry cough, Teresa can’t laugh, the spasms block her throat. Another sip? No. She thinks some confessors incline to frivolity, and in such cases it’s advisable to “be suspicious,” “make your confession briefly and bring it to a conclusion.”18 Then she falls back onto her pillows and closes her eyes again. (Pause.)

TERESA. Not too much affection, if you please, and refrain from too much feminine intimacy. Beware, it smells a bit too much of women around here, don’t you think? (Wrinkles nose.) How often have I told you, daughters, not to be womanish in anything, but like strong men? And if you do what is in you to do, the Lord will make you so strong that you will amaze men themselves.…He can do this, having made us from nothing.19 Do you understand, Ana, Teresita? Do you, Catalina de la Concepción, Catarina Bautista? Be like strong men!

(Her lips sticky with dried blood can barely part to let the hoarse voice out. La Madre is almost shouting, to the alarm of the nurses she has so sternly told to change sex.)

ANA DE SAN BARTOLOMÉ. This is most unwise, Madre! Calm down. A nineteenth-century writer called Joris-Karl Huysmans will credit you with the virile soul of a monk.

TERESA. I thank him! But he clearly doesn’t know me very well. (Reading.) Ah, daughters, I have seen more deeply into women’s souls than any future pathologist! No, I am not referring to my admirer and enemy, the one-eyed Ana de la Cerda de Mendoza, princess of Eboli, in religion Ana de la Madre de Dios; after all, she and her estimable husband Prince Ruy Gómez provided for the foundation of two discalced monasteries.20 You’ll remember nonetheless that as soon as her husband died, the lady ditched her six children and became a Carmelite, to be more like me, and then caused me no end of trouble with the padres of the Inquisition! God have mercy on her soul! A formidable battle-ax, that Eboli. Good King Philip was right to summon her back to her maternal duties…(Pause.) Is that true, or am I dreaming, in revenge? Calling herself Anne of the Mother of God, as if she were Mary’s child, that was bad enough. Girl child or boy child, who’s to say? (Wrinkling nose.) Did I tell you how she arrived at the convent? In a hermetically sealed cart, again to be like me, but with a full team of maidservants and luxury furniture for her cell.…You see the kind of person she was? I could weep!21

(La Madre starts choking again, and Teresita hastens to fetch a jug of cold water.)

ANA DE SAN BARTOLOMÉ, fussing is her way of showing love. Are you sure she wouldn’t prefer it hot?

TERESA, revived by anger. Finally earthly justice dealt with that pretentious woman as she deserved. Did you know, girls, that Eboli was convicted of plotting with the secretary of our dear King Philip to assassinate Escobedo, the secretary of don John of Austria? She was locked up in the Pinto tower. I can see it now, she will die in prison at Pastrana, and then it’ll be up to the court of the Last Judgment. In all humility, grave sinner though I am, I am glad not to be in her shoes.…(Falls backward.)

LA MADRE, with her carers

ANA DE LA FUERTÍSIMA TRINIDAD

BEATRIZ DE LA MADRE DE DIOS

CASILDA DE PADILLA, CASILDA DE LA CONCEPCIÓN in religion

CATALINA DE CARDONA

AN ANONYMOUS NUN

MARÍA DE OCAMPO, MARIA BAUTISTA in religion

MARÍA DE SAN JOSÉ

EMPRESS MARIA THERESA of Austria

TERESA DE LAYZ

With, passing through:

ISABEL DE SANTO DOMINGO

ISABEL DE SAN PABLO

ISABEL DE LOS ÁNGELES

ANA DE LOS ÁNGELES

After swallowing some water from the glass proffered by Ana de San Bartolomé, Teresa sinks back onto the white sheets. There will be no rest. The specter of the princess of Eboli hovering around the bed charges her with fresh energy. The dying woman finds great entertainment in the parade of complicated female souls.

But she lacks the strength to name her thoughts; they are only visions floating before her open eyes, blurred by tears, a down of memories; hazy shadows, opalescent or brightly hued, filling the frigid cell, flowing out of Alba de Tormes and rising heavenward with Teresa.

Here is María de San José, the prioress at Seville, the cleverest and craftiest, the one to watch. She is wearing a fox pelt over her habit.

LA MADRE. I noticed you at the palace of Luisa de la Cerda, do you remember, daughter? (Stares at her for a long time.) Trained by the greatest lady in Spain, you were a scholar, a rare jewel, speaking and reading Latin, an enchantress in prose and verse and all the rest.

(Teresa is thinking these memories, but not formulating them in words.)

MARÍA DE SAN JOSÉ. Your sanctity entranced my soul at once. “She would have moved a stone to tears,” I kept saying to anyone who’d listen. (Remembering, silent.)

LA MADRE. How many letters did I write you after by the grace of Jesus you became prioress at Saint Joseph’s in Seville? Dozens? And I’m sure you knew why at the time. (Pause.) Out of respect for your wisdom, undoubtedly. But also, or more so, because our mutually cherished Fr. Gratian wouldn’t budge from Seville. (Falls back. Palpitations.) You knew, didn’t you? What I mean is, he wouldn’t budge from your side. (Her throat tightens further, no air gets through.)

María de San José has not forgotten the tensions, the recriminations, the quarrels. A blend of affection and jealousy linked and opposed her to La Madre. Today she lowers her eyes, she won’t say a word. Teresa for her part is mentally rerunning the many equivocal pleas she addressed to the prioress.

TERESA, reading, vehemently. “Give us even more news about our padre if he has arrived. I am writing him with much insistence that he not allow anyone to eat in the monastery parlor…except for himself since he is in such need, and if this can be done without it becoming known. And even if it becomes known, there is a difference between a superior and a subject, and his health is so important to us that whatever we can do amounts to little.”22 Serve him some fish roe, an olla podrida if you can, and why not some salpicón.…(Smothered laugh.)

MARÍA DE SAN JOSÉ, unable to resist self-justification. You’re saying, Mother, that we should make an exception for him?

LA MADRE. If only you love me as much as I love you, I forgive you for the past and the future. (Teresa is not listening. While she lived, didn’t she do everything in her power to look into the soul of this fascinating woman? Tonight, let the visitor listen to her.) “My only complaint now is about how little you wanted to be with me.”23 (She looks steadily at her. Over and above their mutual fondness, the pivot between them was Gratian. Who could fail to realize it? Not they, at any rate.)

TERESA, thoughtfully. “For goodness’ sake, take care to send me news of our padre.”24 (Pause.) “Oh, how I envy your hearing those sermons of Father Gratian.”25 “I am worried about those monasteries our padre has charge of. I am now offering him the help of the discalced nuns and would willingly offer myself. I tell him that the whole thing is a great pity; and he immediately tells me how you are pampering him.”26 (Wrinkles nose.)

“Please ask our Father Gratian not to address his letters to me, but let you address them and mark them with the same three crosses. Doing this will conceal them better.”27 (Lips moving.)

“Never fail to tell me something just because you think his paternity is telling me about it, for in fact he doesn’t.”28 All this commotion about Fr. Garciálvarez, the meddling of Pedro Fernández and Nicolo Doria.…Write to me without delay, for charity’s sake, and tell me in detail what is going on. (Smile fades.)

The sentences roll through her mind. In 1576 she was obsessed with Fr. Gratian, while he was loath to leave Seville—he obviously preferred the sparkling company of María de San José. Or did he?

LA MADRE, an incisive dialogue breaking into her dreamy monologue. Do you remember when the superiors of the order wanted to send me to the Indies to separate me from you? That is, to separate us, me and Fr. Gratian.29 (Teresa sinks back feebly. María looks unruffled: she knows all about this kind of female play-acting.) Was Gratian so naive? He timed his moves too cleverly between the two of us for that.…Yes, he was a chess player too, not as good as me perhaps, but not bad.…(Pause. Long silence from both Mothers.) “Our padre sent me your letter written to him on the 10th.”30 Above all, and this is an order, “do not oppose or regret Father Prior’s leaving.” Don’t be like me. “It is not right for us to be looking out for our own benefit.”31 (Pause.)

“You must have enjoyed a happy Christmas since you have mi padre there, for I would too, and happy New Year.”32…(Another choking fit, her lungs are full. That confounded prioress from Seville!) I don’t see why I shouldn’t tell you that I saw more clearly into Gratian than you thought. “I was most displeased that our padre refuted the things said against us, especially the very indecent things, for they are foolish. The best thing to do is to laugh at them, and let the matter pass. As for me, in a certain way, these things please me.”33 (Leaning back again.) But let’s get back to you, if we may. “I would consider it a very fortunate thing if I could go by way of Seville so as to see you and satisfy my desire to argue with you.”34 Now we are in 1580 and I am very old, aren’t I? Tell me how you feel, and how happy you must be to have our padre Gratian nearby. “For my part, I am happy at the thought of the relief for you on every level to have him in Seville.” (Lips. Wrinkled nose. Retching.)

Have they made up, these true-false friends, now that the end is near? That would have been too easy. A gob of blood. The dying woman gasps for air. And spits out the anger pent-up in her old body, anger that had filtered through her pen at times but will now burst unrestrainedly from the compression of her thoughts: judgment before forgiveness.

LA MADRE, beginning quietly. What can I say, you are a great prioress, by all accounts. And a famously learned woman, a letrada, no one else comes up to your ankle, let alone me, my lovely, you’re a letrada all over.…(She gets the giggles, chokes, marks time.) But take it from me: I was upset by your foolishness, and you lost much credit in my eyes. (Stares at her for a long time.) You are a vixen, and I don’t use words lightly. If death is an almighty carnival, and hardly an amusing one, our masks still get truer as we pass over toward the truth that only exists in the Beyond, and I know you follow me on that point at least.…Where was I?…No surprise to see you wearing the skin of that crafty beast I compared you to, over your habit! Because you introduced, into our saintly community in Seville, a greed I could not bear. (Flared nostrils.) You’re certainly shrewd, beyond what your position required. Very Andalusian, really. You were never openly on my side. I can tell you, I suffered a lot on your account. Whatever possessed you to put it into the poor nuns’ heads that the house was unhealthy? It was enough to make them fall ill. When you couldn’t sort out the interest payments on the convent, you had to infect them with this strange extra fear. (Bends head, reading.) Do you suppose such matters are part of the prioress’s vocation? Well, I finally complained to Fr. Gratian about you, absolutely, I got it all off my chest. And why shouldn’t I?35

(María de San José remains silent, looking down.)

LA MADRE. Stop avoiding my eyes, it’s over, I’m done here on earth.…It’s no use, she doesn’t dare look at me. (Shakes head from side to side.) You are tough and pigheaded, my dear, you resist me like you did when I wrote you those furious letters. It was like trying to make a dent in iron. Get away with you, then, adieu! What’s keeping you? Of course I forgive you, away, be off!36 (Waves hand, turning face to the wall.)

La Madre has hardly regained her breath when another of those complicated females appears before her tired but vigilant gaze: María de Ocampo, the cousin whose idea it was to revive the Discalced Carmel, and who would be prioress at Valladolid. Another snooty soul, and sly-faced with it—passing judgment on all and sundry from her lofty perch. She rushes, cooing, to embrace the patient. La Madre withdraws to her innermost refuge, closes her eyes, holds her breath, plays dead. Her thoughts are more eloquent.

TERESA, reading, in an angry voice. “I don’t know how from such a spirit you draw out so much vanity.”37 No, I won’t let her brag of having seen me on my deathbed. Let her reread my letters. I told her and wrote her a thousand times: it is selfish of you to care only about your own house! I dislike the way you think there’s no one capable of seeing things as you do. You think you know everything, yet you say you are humble. How dare you presume to reprimand Fr. Gratian! (Wrinkled nose, nausea.)

(The defendant remains silent.)

TERESA, staring intently at María de Ocampo. Yes indeed, this woman, my own relative, who I myself propelled into the coveted post of prioress, had the impertinence to meddle in what was none of her business! How could she have the slightest idea of what it means to talk to Gratian? Speaking with him is like speaking with…an angel, which he is and always has been. My friendship with this father troubled her soul, did it? Well, I did what I could, and I’m not sorry. (Straightens up in bed, lodges a pillow at her back, harangues the insolent phantom with closed eyes and disdainfully moving lips.) I call it a friendship, if you want to know. Friendship sets one free. It’s completely different from submission, and that’s what you never understood, my poor child. To think you wanted to “save” me from Gratian! (Forcefully.) Save me and send me back to Fr. Bánez, whom I was neglecting, in your opinion! So off you went almost every day with your nasty gossip to the illustrious Dominican, trying to turn him against me and Gratian! You proved inflexible, a stance no one has ever taken with me. Yes, inflexible, to put it mildly.38 (Pause.) No, I won’t open my eyes, you will have to leave unseen. You will be pardoned without the light of a look, without brightness. That’s all. It’s too much already. But forgiveness is my religion, as it is yours, in principle. “A wise man does not bar the room of pardon, for pardon is fair victory in war.”39 Who wrote that? (Teasing smile.) A “wise man,” perhaps, does not. Much harder for a woman. So what am I? Nothing. Go away now, you have my forgiveness, of course. But for pity’s sake spare me your presence.…Farewell, daughter!

Teresa represses a desire to vomit. She mustn’t, it only suits young bodies, young women; the dying must make do with the rising gorge of revulsion. She clings to her friendship with Gratian, just to show María Bautista what it is to be a woman: a woman of God, obviously, both here and in the afterlife. But a woman nevertheless, always in want of something or other—in want of love, what else.

TERESA. That prioress of Valladolid was smarter than me, perhaps. For one, she never wrote Gratian until he’d replied to her previous…at least, that’s what she said.40 It’s different with me, I’ve always been the servant of our padre, his true daughter, and it’s no concern of María Bautista’s what went on between him and me, Him and me.…Who is He? May our Lord be with us.…My head is so tired.…(Voice cracks.)

Muffled footsteps, rustling habits, wet towels, cold water. Catalina de la Concepción and Catarina Bautista have come to take over from Ana and Teresita. La Madre meets their tender, vacuous gazes, her eyes try to smile, her lips quiver almost imperceptibly.

TERESA. We are not lovely to look at when we die, but some of us are luminous. I don’t mean that a confession trickles at last from our naughty-baby mouths—for babies is what we become at the end—but…(pause). What comes out are ranting commonplaces, ready to be staged years hence by a certain Beckett. Rarely something original or striking. But one doesn’t fear Nothingness, and when not cursing this vile world while waiting for Godot, one may find one’s tortured, waxen countenance becoming lit by a futile glow.41 (Fast.) All things are nothing, and that’s fine. (To the two carers.) Don’t you worry, my dears. There is a great difference in the ways one may be.…

Having tasted of spiritual wedding in life, Teresa now expects nothing from her Spouse but total dispossession. She will be emptied of Gratian, also. The ultimate mystery: Could Nothingness actually be Being? “Mas habéis de entender que va mucho de estar a estar.”42 The two nurses are bewildered: Is La Madre delirious, or is she seeing the Spouse? Already? Probably the latter, since she’s smiling.…A hideous smile all the same, stretching the lips that babble sounds in which the carers can only make out two, wearisome, obsessive words: all and nothing, nothing and all…todo and nada.…Silence.

In a flash, look, a few vice-ridden little hussies skipping past. One is the anonymous novice, who will remain anonymous: it was she who spread the rumor about discalced nuns scourging each other while suspended from the ceiling.

And this better-looking one, Ana de la Fuertísima Trinidad, a nosey parker who was always ferreting through my business, as if she wanted to impose an illegitimate proximity on me, or maybe she was a spy, but whose? The princess of Eboli? Officials of the Inquisition?

As vices go, I prefer ambition and scope, thinks Teresa. In the style of Catalina de Cardona, say. Here she is: I project the black shadow of this melancholic soul over the Alcázar gate that pierces Avila’s girdle of walls.

TERESA, calm and composed. You exerted quite a pull on me, as the daughter of the duke of Cardona, I can tell you that now, in the endgame of the end. (Pause. Cheeks reddening, elbows sunk into the mattress, makes huge effort to straighten up, fails, tries again.) You were governess to the ill-fated prince don Carlos, son of Philip II, weren’t you? And also to don John of Austria, the illegitimate child of Charles V? (Wrinkles nose.) Because I’m always attracted by rank and honor, nobody escapes the family sin, I know it. Your noble self, as a doña, had considerable appeal for me, I must admit. (Hands fingering veil, adjusting it on head.) Then, suddenly, aged forty, you marched into the desert of La Roda, laden with penitentiary chains and blood-soaked hair shirts, in the sole company of your demons—gray serpents and fierce mountain cats. Not to mention fasting, dear me, every day but Tuesday, Thursday, and Sunday! (Gabbling, out of breath.) You chose to wear a monk’s cowl, and I’ll be frank, to me you’re just a kind of transvestite. At the Escorial palace, did Princess Juana and King Philip invite you in that guise? I had to put up with you; my penances were small fry, compared to yours. I wanted to equal you, which was confusing. That’s it, I was overcome with confusion when I thought about you—especially when the Toledo community, a convent you once briefly visited, described being enchanted by the odor of sanctity emanating from your clothes, although it strikes me that your grimy habit could not but stink to high heaven. I can’t help it, you see, I hate bad smells, I dread them, I run from them, there we are. (Getting redder and more voluble.) I trust my corpse will not be smelly, I’m sure it won’t be. Here, have a vision, I’ll share it for free: long after my death some good sisters will discover my fragrant body—so unlike yours, do you get me?—under a heap of limestone rocks (of course), and the news will astound the world. Jealous?

(Catalina de Cardona’s shadow remains mute. No sign, no sound, petrified in its transvestite pose.)

TERESA, in a hammy, pseudo-humble voice. I felt all mixed up before you, oh yes I did, and I confess it. His Majesty understood, and reassured me: “I value your obedience more,” His voice told me; you can imagine my relief. I didn’t ever get to be as mortified as you, or as dirty, and certainly not a man, needless to say—ha ha ha! (Open-mouthed, is she expiring, gagging, or laughing?) I know all about obedience. Most of the time I obeyed as sincerely as I could. Quite often I did so playfully, I can say that now. The Lord knew it, for nothing eludes His infinite wisdom, and He let me, because if I was pretending it was only to please Him. (Pause.) I know how to obey, then. Despite the hardness of my heart, which is certainly male. Harshness, too, I cultivated just to please my Spouse! But not in your way, oh no! A female I was and a female I find myself to be, for the purposes of suffering, of course. And for those of enjoyment, obviously! Especially! Not like you, no. But sure of His love, in sovereignty, like Him, whatever else might happen. With or without Gratian. With everything and with nothing.…You’d never understand. You see, we belong to two different species. There is a great difference in the ways one may be…(Smiling.) To bud forth, to be drenched in water like a garden, streaming with joy, to say yes to everything, to nothing.…(Smiling again.) What else is there to do? To write, to make foundations, to hurry, because time is getting short, to lie…Truly I say this unto you.…(Lips.)

At these words the black shade of Catalina de Cardona disappears from the place where Teresa was amused to see it—the Alcázar gate in the ramparts of Avila—and takes refuge, offended, in Carmelite memory.

LA MADRE, with

ANA DE SAN BARTOLOMÉ and TERESITA

CASILDA DE PADILLA

BEATRIZ DE LA MADRE DE DIOS

TERESA DE LAYZ

MARÍA ENRÍQUEZ DE TOLEDO, Duchess of Alba

The voice and ghost of the EMPRESS MARIA THERESA

The opalescent light of the death scene grows paler as the hours tick by. Even though La Madre knows her Spouse is waiting, her old, shrunken body cries out for motherly caresses. Does she really exist, this “mother without flaw”? Teresa no longer utters a word. Only her mind, the thoughts that leave her behind as they flee toward the Lord, clothe the visions—those wings, those ships—carrying her to Him.

That young noblewoman advancing toward her bed, isn’t that Casilda de Padilla, the daughter of the Castilian adelantado, Juan de Padilla Manrique? Her father died when she was very young, leaving her to be raised by her mother, María de Acuña Manrique, and guided by her confessor Fr. Ripalda—the inspired Jesuit priest who ordered the writing of the Foundations.

TERESA. I miss you, daughter. (Now her words run through the dying woman’s mind, through neurons that obstruct or let them pass, but no word is uttered.) Why did you leave me? Barely a year ago, it was. For the Franciscans of Santa Gadea, near Burgos, I seem to recall. (Long stare.) I recognized myself in you, or rather not—you ranked so far above me. And again, I hated that stubborn taste of mine for the finer things that drew me to you, that ambushed me in my unwitting state as a semi-Marrana determined not to know, that made me laugh at myself when I caught myself being so frivolous! First, from tender youth, like me you despised the world. (Fast.) They found a way to betroth you to a brother of your father’s, so as to keep the fortune and the family name; your brother and one sister had already taken vows, that was enough, they thought. Your parents obtained a papal dispensation to license the match with your uncle. You were only twelve at the time. You fled to a convent, they dragged you out, you went back, your uncle-husband got you out, you fled again, but this time you came to me, to the house at Valladolid.

(The film rewinds inside her head, the brain sees, speaks without uttering, scrambles, speeds up, bumps into itself.)

Let’s begin at the beginning, shall we. Your story reminds me of my own paternal uncle, the pious, unforgettable Pedro Sánchez. (Jumpy encephalogram.) No connection? You’re right, there isn’t. Except, and this is the point, that Uncle Pedro was the one who made me decide to take the veil. I can admit it now. Nobody knows, only you. Do you see? My story was the exact opposite of yours: I didn’t marry my uncle, he made me marry Jesus. Strange, isn’t it? By the grace of God, I escaped sooner than you did from the fate reserved for women, mothers, families. You took your time. You tried to do it through me. At last you obtained what I offered, didn’t you? (Pause.) In matters of love only the Other’s love endures, don’t you agree? The rest, including the attractions we feel as women, or especially those, is insoluble: the shadow of the mother gets in the way, do you follow me?

Teresa contemplates her reflection in Casilda de Padilla’s specter, plunges into the other’s life before retreating, lucidly; doubles briefly back onto the self to loop the loops of the writing and the girls’ portraits sketched out in the Foundations. That’s not me, is it? It’s not me so who is it, who is she, what is a Me? Exile or castle? Dwelling places, maybe, but no me, there is no Me…unnameable Me that tells lies, basely splashing in the unnameable fount divine, of the Word rejuvenated.…

TERESA, like an excited little girl. Is that still you, Casilda, or have I got you mixed up? Do you know you’re dressed like doña Catalina, my father’s first wife? In the clothes that were packed away in wardrobes and precious chests. How can that be.…

CASILDA. You dressed me yourself, Mother, just now, with your own hands. (She’s trying to explain that it’s all happening in the older woman’s foggy mind. Or is it La Madre speaking, taking Casilda’s role? She stares at the visitor for a long time. Superimposed images, chromatic deluge.) You picked out this shantung skirt, made from the watered silk of old China, with a bias binding in slashed yellow taffeta and a red lining. And this violet damask bodice, ribbed with black velvet. You used to say your mother Beatriz used to put them on when she wasn’t feeling sad, until, near the end of her life, she wore nothing but black…

TERESA. That’s right, I did, I remember now! (Carried away by reminiscence.) And you used to speak so sweetly about your own mother, and the joy and fun she gave you every day, that I felt quite at home. And yet that same wonderful mother provoked violent inner struggles in you, with her sainted praying. (Raising hands and holding them up, open, before eyes.) To be faithful to such a perfect mother, as I tried to be to mine, you couldn’t do better than leave the world that had caused her such grief, reject your marriage, and keep all your love for the holiness she herself aspired to, though she lacked the courage to pursue it wholeheartedly. Are you with me?

CASILDA. I thought I cared for my betrothed, Madre, much more than his age might warrant. Rather as you loved your Uncle Pedro, if I understand correctly…(Reading from the Foundations.)43 “At the close of a day I had spent most happily with my fiancé…I became extremely sad at seeing how the day came to an end and that likewise all days would come to an end.”

TERESA. All is nothing, I realized that at the same age you did. Or earlier. (Pause.)

CASILDA. I began to hate the world in the midst of its pleasures. (Pause.)

TERESA. We are much alike, daughter, and I love you because you persevered. Your mother couldn’t bear to lose you to a nunnery. God bless mothers who pray on the one hand, and cherish worldly vanities on the other; such mothers sow war in the souls and bodies of their daughters. And war is the only thing worth living, my daughter; I mean it. Peace? (Pause.) Ah, peace! You too, you mouth it like everyone else, “Peace! Peace!” You, of all people! Peace doesn’t exist, my heart. There is no peace, remember Jeremiah! (Voice cracks.)

Casilda de Padilla will never know the thoughts of a mind now beyond the power of speech. She is full of her own story, as we all are.

CASILDA. Father Báñez believed in the sincerity of my vocation. Twice I entered the convent at Valladolid, and twice I was expelled, even though I’d already put on the habit. I got no support from my mother; did she think I was being childish, or that I was possessed? (Pause.)

TERESA. Maybe she wanted to test you? That’s what she told me, and your mother was a holy woman, my girl, believe you me. (Momentary smile.) So you worked out a compromise between you as follows. You signed away all your goods and assets, dear Casilda; that’s what it comes down to, choosing the religious life. Which is to say, choosing me—clear as day. Then your mother arranged with Rome to whisk you away from my lowly Carmelite house to become abbess at Santa Gadea, a convent founded by your own parents. Thus the family honor remained safe; but as for ours.…Let’s drop the subject, shall we? (Breathes out.)

(Teresa is smiling, yet there’s no detectable expression on her placid face. Ana de San Bartolomé thinks she must be with her Creator. But she’s not there yet. Her mind wanders back to her part in Casilda’s story, for this was one of her favorite daughters.)

TERESA. I can still see the way you lost your pursuers! (This movie doesn’t bother her, on the contrary, it’s entertaining.) Once you got safely into our house, your habit went straight back on. It suited you, it still does, I must say. But I hope you don’t mind if I like you better this way I dressed you just now? In that festooned skirt and purple bodice, Sister, you bring my mother’s youth back to me! Between ourselves, our rough habits never make us forget that we’re women. (Pause.) There’s always something underneath.…Do you find that funny? (Pause.) And those unspoken wars the mothers waged, they passed them down to us, via invisible and downright twisted paths. But I can’t stop thinking that those paths, those secret conduits, are precisely what make us so quick to turn toward the Lord, and so amenable to that divine Spouse. (Forcefully.) Come now, don’t look so embarrassed! Keep them, keep the skirt I put on you and the top as well, I’d have given you all of Catalina’s clothes if I could. I like you. You please me because you please the Lord, it’s that simple, there’s no sin in it. It’s a game, let’s be merry, daughter, it’s only a game.…And playing is not forbidden, take it from me. Only today, for instance.…(Pause. Asleep. Dreaming.)

(The mind journeys, but the stiffened body does not move. Has she become paralyzed?)

Ana, Teresita, I don’t sense you anymore, are you there? (Wakes up, full face.) I know you can’t hear me, my voice won’t come out. I’m cold. This blue air chills me to the bone, I wish there were some warm arms around my neck. I long for nurturing breasts, soft lap. Hot water, the four waters of the divine garden. Can’t you see that I’m a newborn babe? Bathe me, fill my mouth with warm milk! (Convulsions. Thin trickle of blood from corner of mouth.)

I’m shivering, but only because I’m too lightly dressed. This fresh breeze, so airy and sharp-edged, tells me I’m in Avila, is that right? (Fervid reminiscence. The serial goes into historical-epic mode.) Father let me wear the white silk gown with pearl trimmings and lilac-pink stitching over muslin sleeves, the one Mother wore when Charles V came to town. And those leather ankle-boots I loved to see on her. Today’s a holiday, I’m sixteen, and the Empress Isabella is coming with little Prince Philip, who is only four and who will become His Catholic Majesty King Philip II. (Fast.) To swap one’s infant garb for a sovereign’s finery, what a tiresome ceremony: flamboyant celebrations, head-spinning fuss. Then that feeling of emptiness and discomfort, me trembling and shivering like I am now, look, in this lovely dress of white and old-rose silk you’ve decked me out in, I know you meant well, but it’s the middle of winter, be sensible, children.

(No answer. La Madre can no longer hear the nurses whispering, her mind spins upon itself inside the crystal castle of her soul. No, it’s a castle of snow and ice that’s either melting or hardening, it depends. A delicate confusion merges dwelling places, years, silks, contours, beings.)

Is it me arrayed in queenly splendor, or is it you, my daughter? Father Gratian’s favorite, little Beatriz Chávez? (Stares at her for a long time.) Another one with my mother’s name; the Beatrices are definitely keeping me company on this last voyage. And you even took the religious name of Beatriz of the Mother of God! Like our dear padre, that noble squire of the Virgin, who chose the same name to become Jerónimo Gracián de la Madre de Dios. I presume you noticed the coincidence? (Pause.)

Ah, that Mother of God, how desperately we reach for her when our own fails us! It would be an understatement to say you lacked a mother, Beatriz dear. (Attempts sweeping movement with arm. Falls back.) She was unkind and a bully, quite unlike other mothers that have been coming to my mind ever since I’ve lain dying in this freezing cold, for how many days now?…Anyhow, not really a mother at all, not like mine, nor like the way I attempted to be a mother myself, although, God forgive me.…(Pause.) He knows how flawed I am. (Pause.)

(Beatriz de la Madre de Dios makes the most of this sentimental moment by acting the little girl, and a pretentious one at that: she’ll never change.)

BEATRIZ DE LA MADRE DE DIOS. In centuries to come, people will say that I was an abused child, won’t they, Madre? You went into detail about my ill-treatment in the Foundations, in the chapter about the painful process of foundation in Seville.

TERESA. Appalling, to leave a seven-year-old mite with her aunt! They may have been rustic mountain folk, but your parents were Christians, like everyone else! (Falls back.)

(Beatriz doesn’t reply at once, intent on her own history as though drunk on bitterness.)

BEATRIZ DE LA MADRE DE DIOS. And then those three servants, who were after my aunt’s inheritance, accused me of trying to poison her with arsenic!

TERESA. To be honest the idea doesn’t seem to me so far-fetched (full face again), in an abandoned child who would do anything to get home to her mother. We can admit these sorts of things now, can’t we? This Hell on earth is well behind us, I mean behind me, and the cold air is already carrying my body, if not yet my soul, up to Heaven.

BEATRIZ DE LA MADRE DE DIOS. You are more au fait with all that than I, Mother. How can I remember what happened when I was so little? I do know that when Mother got me back, she gave me a scolding and a whipping and made me sleep on the floor every night for more than a year.

TERESA. And yet your mother was virtuous and devoutly Christian, like mine! (Long pause. A joyful expression gradually forms.) Aren’t human beings strange! You’d think the Creator had not made us all of a piece, but out of mismatched scraps. As a result we all have several faces. You in particular, my child, it’s a veritable curse.…Unless it’s a stroke of luck, a kind of grace or freedom, do you follow? One of the most enviable of God’s gifts, the ability to travel through our innermost spaces in a kind of pilgrimage.…

(Beatriz goes back to poring over the twisted threads of her misfortune, not listening to La Madre. Teresa, carried away by storytelling, is not listening either. She has already written this drama, she contents herself with gleaning a word here and an image there. Hopeless, toxic female contiguity.…)

TERESA. Ah, so your father passed away? (The movie allows itself some melancholic frames.) You never told me about that…and your brothers died as well? The Holy Virgin had to take you under her wing to ensure that when you were around twelve, you stumbled on a book about Saint Anne and developed a great devotion to the saintly hermits of Mount Carmel. (Joyful expression returns, more intensely.) Like me, you chose virginity. Clearly the best choice of a bad bunch. Fatherless and miserable, harried by your poor mother, who couldn’t help taking it out on you, you barricaded yourself behind your hymen. (Thin smile, fading.)

BEATRIZ DE LA MADRE DE DIOS. I wanted to die a martyr, like Saint Agnes. Father and Mother beat me almost to death, then they tried to choke me.…I was confined to bed for three months, unable to move.…I wanted desperately to lose myself.

TERESA. Lose yourself, child? (Leans back to inspect her.) Thanks to the love of Christ, you were saved! To suffer like Him is pure glory. Once you felt affinity with the martyrs and the Passion, your family’s harassment was transmuted into a token of love, wasn’t it? (Long pause.)

BEATRIZ DE LA MADRE DE DIOS. There was only one way out for me: to become a nun.

(Teresa seems to be suffocating again, she gasps for air to the alarm of Teresita and Ana. She thinks of the other Beatriz: Beatriz de Óñez.)

TERESA. Beaten children, abandoned children, it’s all the same: that’s what you are, my darlings. (The sequence of images is overtaken by darkness.) Primed to take shelter in the bosom of the tortured Father whom I call our Lord. (Turns to face us.) My sisters, you are, and I along with you, we are the paler twins of the Lord on Calvary. The Lord who allowed Himself to be tortured, abused to death if you like, in order that we might merge with Him, fuse our flesh with His, and thus and only thus be saved along with Him. (Sudden vehemence.) You see, little one, you can escape from a degraded or violent mother, flee a falsely respectable and profoundly distressed family, but you can never, ever, get away from Him. We poor mistreated creatures—and what creature is not?—could only be saved by a Father as cruelly flogged as we were, who loves us and saves Himself, and thereby saves us too. (Voice cracks.)

(The Chávez girl will never hear the catechism lesson La Madre recites to herself in order to make sense of her life and death. Beatriz is still hung up on her own adolescent yearnings.)

BEATRIZ DE LA MADRE DE DIOS, in a perverse whine. I couldn’t find a good father confessor anywhere, Mother.

TERESA. That’s the way it goes, perfectly natural, my child. (Smiles.) But you are a shocking little flirt, let me tell you plainly.…As plainly as I allow that your mother was a wicked bully, in her way. (Knowing smile.) No need to blush! I can tell your cheeks are on fire, even with my eyes closed. (Turns her back, settles on side with face to wall.) I’ve known you long enough.…(Breathes out.)

I know you like the back of my hand, in fact, and you hardly need me to tell you why: because of Gratian. Yes, him again. (Pause.) Not knowing how to become a nun, you became depressed, and started haunting churches, looking haggard. An old white-bearded Carmelite did his best to convince you that God had already made you strong, since you’d survived your decomposing family, but that wasn’t enough, you were on the lookout for something else. What could it be? (Smile fades. Lips.) The arrival of young Fr. Gratian on the scene lifted you to seventh heaven. You went to him for confession at least twelve times—oh, I know every detail!—you stalked and harassed him, in fact. (Vehemently.) He was wary of pretty airheads like you, I made sure of that, I wrote to him endlessly on that topic, as on many others.…Finally a lady interceded for you, and the painful richness of your soul was comforted: you clung to him like a limpet, determined not to let go!

(It would take a lot more to dislodge that little pest of a Beatriz.)

BEATRIZ DE LA MADRE DE DIOS. It was the feast day of the Holy Trinity, 1575, when you came to Seville, Madre, that I ran away from my parents’ house to take refuge in the convent. I was your first novice, remember? You made me eat properly, I put on weight, I made peace with my mother. A few days after my profession of faith, my father resigned himself to die, and Mother came to join me at the convent.

TERESA. Nothing ever made me so happy as to see mother and daughter devoted to the service (effortfully turning over, stares at her for a long time)…the service of One who proved so generous toward them.

BEATRIZ DE LA MADRE DE DIOS. Mother and I? Or do you mean you and I, Madre?

TERESA. Mothers and daughters, you know, can never be reunited in this world. (Rubs finger over lips.) So much passion, so much rivalry, with love thrown in; and love is at its murkiest between a mother and a daughter. But there is a way to solder them, the only way! Remember what I am about to tell you, hic et nunc. Were female cohabitation possible at all, it is only possible in the name of His Majesty, a Third Person: that’s what the true, Catholic, Roman, and Apostolic religion teaches. Will you remember that? I hope so, for your sake! As for the rest, between ourselves.…(Nose, lips.) Some of the father confessors God sends us are deplorably frivolous, in my experience. (Reading from Way.) “If this confessor wants to allow room for vanity, because he himself is vain, he makes little of it even in others.”44 Be forewarned! (Pause.) You aren’t obliged to agree with me. In reality, Sister, you are quite incapable of having any opinion on this subject. Besides, these gentlemen are inclined to render us mistrustful of one another, it’s well known.…(Gravely.) Why do you suppose I wrote a whole chapter about you, the twenty-sixth of my Foundations? It was because I knew the story would gratify him, who adored you. Of course I mean Fr. Gratian, who else? A foundation, you see, rests upon a host of stories like that, what did you think? (Tries mechanically to adjust veil, forgetting that she is bare-headed.) And it has a great deal to do with raptures, something else I daresay you know nothing about. Ah, they are impossible to resist, and cannot be disguised. On those days I am like a drunken man, I entreat God not to let it come over me in public! As for the lascivious feelings that come afterward, and that other people have mentioned to me, I pay no attention to them and I advise you to do the same. (Knowing smile.) Actually, I have never experienced this.45 The truth is that I am so cheerful at departing at last toward His Majesty that I can confess all these trivialities to you, trivial creature that you are. But how I always distrusted you! (Rueful smile, followed by nausea.)

(Three knocks at the door. Who is it? Who wakes La Madre from her coma?)

TERESA. Let me go in peace! Dear God, You will not despise a repentant heart? (Lifts beseeching eyes heavenward.)

Father Antonio de Jesús, the old companion of John of the Cross, now a vicar-provincial, has come to witness the agony of the foundress. With him is the new prioress at Alba de Tormes, Juana del Espíritu Santo, a sweet and gentle girl but excessively fond of fasting, in Teresa’s opinion. On grounds that Teresa was junior to the prioress, Juana offered her white linen bedclothes in place of the usual straw mattress, but then left her alone…so as not to be importunate! Father Antonio seemed not to notice this underhand score-settling between women. And now, at the end of the end, sensing the approach of the final hour, the two of them decide to show up—the Carmelite may well become a saint, you never know! But Teresa can’t be relied on to collaborate. She is already floating on another level, waiting to be seized by the “royal eagle of God’s majesty,” “esta águila caudalosa de la majestad de Dios.”46

TERESA. Ah, you must be here to talk business. (Condescends to open eyes a crack.) The battle for the Salamanca Carmel will be my last, and I have some concerns about this latest institution, having formally prohibited that the house be bought. But the prioress Ana de la Encarnación had set her heart on it. (Turns page.) So, it’s you, Teresa, my daughter, Teresa de Layz, I regret that we must meet in these circumstances, but never mind, since it’s God’s will. Come closer, don’t hang back. (A new lease on life, briefly: foundational affairs stimulate her to the last.) I took you, too, for another myself. It was you who founded this discalced convent at Alba de Tormes where I now lie, by God’s grace, on this final leg of my journey. (Reads.) I devoted a nice little “short story” to you, as it will be called, in my Foundations. Don’t thank me, thank the Lord for making you as you are. You had everything to be the beloved daughter: a well-heeled family, noble, pure-blooded parents so as not to feel “sold into a foreign land”47 the way I sometimes did…I won’t dwell on it, but I’m telling you, know it and don’t forget. But no, that’s wrong, it wasn’t like that at all.…(Rubs her eyes, nose, lips.) God wished you to be abandoned also; soon after you were born, your parents left you unattended for a whole day from morning to night, as though your life mattered little to them. So many abandoned girls it pleased God for me to gather up—a sign from Providence, was it not? Providence, no doubt about it, decreed our paths should cross.…What was I saying.…(Hacking cough.) You were their fifth daughter, and people have no use for girls in this ignorant world.48 Now listen, and retain what I say to you: “How many fathers and mothers will be seen going to hell because they had sons and also how many will be seen in heaven because they had daughters!”49 (Stares at her for a long time, then bows head to read from the pages that continue to unfold on the blue cloak of the Virgin, caressing the body on the brink of death.) The times will have to change, that’s all, and I have a premonition that it will be soon…

TERESA DE LAYZ, in a faint voice. The village woman who found me thought I was dead, apparently she said to me: “How is it, child, are you not a Christian?” And I piped up, “Yes, I am,” despite being only three days old, because I knew I’d been baptized; and said no more until I reached the age when all children start to talk.

TERESA. That’s quite a story, my dear; these women tell so many of them! Be that as it may, tell yourself that God willed it so, and don’t attempt to fathom the mystery, we all of us bear its stamp (Stares at her again, with incredulity.) Forgotten by both parents, you knew you were a Christian. An excellent Christian! I myself recognized this about you, or else I should never have let myself be awoken by your visit at this stage. When your parents heard what their baby had said, they were amazed. They would have been amazed by far less. (Coughs again, clears throat.) Full of remorse, they began to lavish love and care upon you.…They were also troubled by your subsequent lack of speech that went on for a long time, I believe! (Widens eyes. Pause.)

TERESA DE LAYZ, reciting her homily. I didn’t want to get married. But then, on hearing the name of a man who turned out to be both virtuous and rich, Francisco Velázquez, I consented at once. He loved me and did everything to make me happy, while on my side, God had equipped me with all the qualities he could wish for in a wife.

No, women never stop telling stories.…And this is another, stranded on its sandbank, jumbling times and places, high on love, children, and disappointment. Teresa isn’t listening, she knows it all in advance, always did. What she had to do was swim on by, let the rest sink, wash herself down, escape.

TERESA. A happy marriage, then. Like my marriage to my Spouse? (Broad grin.)

TERESA DE LAYZ. Not all that happy, Madre, in that it was barren.

(At these words the foundress falls back into her blue chill of agony. The visitor continues prattling about the desire for children, hijos, posterity, generación, and the many devotions and prayers she offered up, all in vain. Teresa thinks nothing. Nothing but the cold that sends icy fingers through the entrails that once were enflamed by the spear of transfixion.)

TERESA DE LAYZ. “Do not desire children, for you will be condemned,” I was told by Saint Andrew, a powerful patron of these causes. And then I seemed to see a patio, Mother, and beyond it green meadows as far as the horizon, dotted with white flowers. Like your gardens, Mother, irrigated by the four waters, fragrant and in bloom. Saint Andrew appeared to me again, saying: “These are children other than those you desire.” At that I understood that our Lord willed me to found a monastery. (In a metallic, conquering voice.) I no longer wanted to have children.

(Teresa remains silent for a long time. Why must this other Teresa rekindle such hoary griefs, incommunicable, forgotten, overcome and buried long ago?)

TERESA. I never wrote about what is now burning the tip of my tongue, and will remain as pure, unformulated thought.…(Fervid reminiscence.) Your story finds an echo in me. Two Teresas, de Cepeda and de Layz, two barren wives who begat religious houses instead of offspring.…(Pause.) You and your faithful husband eventually created Our Lady of the Annunciation at Alba de Tormes, a fine convent, and I’m proud of it. (Pause.) Sincerely proud. (Weeps. Another long, heavy silence.) And now, they tell me that the good donor that you were torments those great souls? (With sudden violence.) “I fear an unsatisfied nun more than many devils!” There!

Teresa de Layz feels the fear of sterility come over her again. If a mother upbraids her daughter, if she deserts her, is it not because the mother is herself unhappy, numbly inadequate, afflicted by some inexpiable infirmity? A dried-up fig, in short.

(The dying woman pushes herself up on her elbows in the white bed with its freshly changed sheets.)

TERESA. Ah, dear lady, one cannot serve God in disquiet. All this is infantile, mere attachment to self. How different it is wherever the Spirit truly reigns! (Turns the page.)

Teresa of Avila can be cruel, all right—just enough to restore order. Up to her last breath, and, if God wills it, piercing her foremost alter egos to the quick.

Father Antonio de Jesús shows Teresa de Layz the door.

TERESA, to Ana de San Bartolomé. Tell me, child, are we still in Alba de Tormes, on the duchess of Alba’s estates? (In a childish tone of regressive nostalgia.) Ah, the duchess! She delivered me for a time, like the exit from Egypt, she nurtured me.…It was her, doña María Enríquez de Toledo, wasn’t it? Or am I out of my mind? I see her now.…(Tries to rise onto elbows, falls back.)

(Doña María Enríquez de Toledo, the duchess of Alba, walks past holding a trout.)

TERESA, in a changed, respectful, courtier’s voice. The grace of the Holy Spirit be always with Your Excellency. Have you received my letter imploring your kindness regarding the house founded in Pamplona by the Society of Jesus? I know, the duke your husband is leading an army into Portugal, and the constable is your brother-in-law the viceroy.…(Whispered aside to Ana de San Bartolomé.) We must absolutely protect the Society as it protects us, don’t forget that, my child…a testament, if you will.…(Respectful voice.) I am very sick, You Excellency, I am bleeding, I am on my way…it is important to me that the favor you show me in everything be known.50 (Quick sigh, soft voice for herself.) The duchess is definitely worth keeping on side. After all, it was she who helped to have my little nephew Gonzalo exempted from serving in the duke’s Italian campaign, dear Gonzalo, who caused me so many headaches after that.…Oh well, I did my best and so did she, and at least he didn’t get killed.51 (Pause, broad smile.) I’ll always remember the nice fat trout you sent me, Excellency, when I was here in Alba, a good ten years ago it must be; a gift from God.…(Tired voice, sigh. Suddenly sits up, reads in emotive voice.) “If you favor us in this regard it would be like liberating us from the captivity of Egypt.”52 (Silence.)

(Broad smile, repeating.) Like liberating us from the captivity of Egypt…liberating us from the captivity of Egypt…from the captivity of Egypt…the captivity of Egypt.…“Let my people go, that they may hold a feast unto me in the wilderness.…And I will bring you in unto the land, concerning the which I did swear to give it to Abraham, to Isaac and to Jacob…I am the Lord.”53 Let my people go…my people…from the bondage of Egypt…deliver me…deliver.…(Coughing fit, long silence. Rest.)

(Teresa wastes not a second of this respite, the clarity that precedes death. She addresses Ana de San Bartolomé.)

My dear child, as soon as you see that I am a little better, please order a cart.…(Barely audible.) Settle me in it as best you can and we will go, you, me, and Teresita, home to Avila (voice breaking).…Do you promise?

ANA DE SAN BARTOLOMÉ. Planning to travel, even with her last breath!

TERESITA, plaintively, in tears. She wants to be close to her parents.…

ANA DE SAN BARTOLOMÉ. I don’t think so. She wants to leave Egypt.

TERESITA. But that’s been done, way back in the Bible!

ANA DE SAN BARTOLOMÉ. Not like that. I think she’s still caught in her own personal Egypt.…

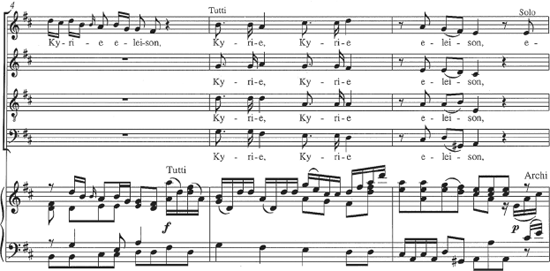

Suddenly, after a few slow bars of introduction, a slender, diffident but cultivated soprano voice is heard. Delicately it sings an unaccustomed Kyrie for a funeral service—from the Missa Sanctae Theresiae, the Mass for Saint Teresa by Michael Haydn. The work was commissioned by the Empress Maria Theresa, and the voice we hear is hers.54

TERESA, surprised, intrigued, attentive. Don’t be afraid, my daughter, nervousness inhibits the voice…as well you know, since at home in Austria you regularly sing the soprano solos of sacred music compositions. (Motherly smile, timidity.) Relax, let yourself go…you are after all the wife of Emperor Francis I of Austria! Come closer, let me hear your tuneful little voice.…Everybody will agree one day that Your Majesty’s musical sensibility was the finest of all the Habsburg line.…You can believe me, it’s your own patron saint telling you.…(Vertigo, slackening, peace invades the spasm-shaken body.)

EMPRESS MARIA THERESA, singing the first movement of the Mass composed for her by Michael Haydn. The choir remains in the background throughout. “Kyrie eleison.…”

LA MADRE. “Bravo!” “Superb!” “Majestic Haydn!” Are those your words or mine? I am not very musical, Majesty, as is well known, and you honor me by associating me to that sort of faith which music is…being the most spiritual…or rather the most physical…that is, both at the same time…or not? (Dreamy voice.) Majestic, yes, that’s what you called the little brother of the greater Haydn, for you could see he wasn’t so little…a Kapellmeister of Salzburg Cathedral, no less.…The young Mozart will learn a lot about sacred music from Michael, no secret there.…He mentions him in letters to his father Leopold.…They will remain friends, even after Wolfgang’s turbulent break with Prince-Archbishop Colloredo.…Music specialists will have a great deal to say about him, as time goes by…yes, I assure you.…Some will point out that Mozart’s celebrated Requiem has much in common with the Requiem composed by Michael on the death of Prince-Archbishop Sigismund von Scrattenbach, another friend of Amadeus. But we’re not at the requiem stage yet, are we, Majesty?…In my case, at least.…Sing on, my daughter, and may God bless your lovely voice.…(Peaceful smile, falls asleep.)