Milton Greenberg, Author and Provost, The American University

Harry Colmery, The American Legion

Representative Edith Rogers (R-MA)

Representative Dewey Short (D-MO)

Robert Maynard Hutchins, President, University of Chicago

Senator Bennett Champ Clark (D-MO)

Franklin D. Roosevelt, 32nd President of the United States

James Michener, Author

Anthony Principi, Secretary of Veterans Affairs, 2001-2005

SONNY’S SUMMARY

Knowing the unemployment and poverty that many of his fellow veterans faced in 1918 after World War I, Harry Colmery of The American Legion drafted the World War II “GI Bill of Rights” in December 1943. Although there were several champions of the “GI Bill” in Congress, the list of opponents initially included university presidents, labor unions, and some veterans’ organizations. Not before Congress held 22 hearings and took multiple votes did the GI Bill get to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s desk to be signed into law. After the war, 7.8 million veterans used the GI Bill for education and training, largely in skilled trades, business, industry, and engineering. Disciplined by duty and enlightened by experience,2 they were resoundingly successful at trade and business schools, on college campuses, and in the workplace through structured, on-job training and apprenticeships. In a law that had few grand expectations, veterans’ initiative in pursuing education and training under the GI Bill made the United States the first predominantly middle-class nation in the world, as author Michael Bennett said.

Mr. Montgomery

In a broad sense, the “GI Bill” concept emerged during World War I.4

However, World War II was raging in Europe and the Pacific in June 1944 when Congress sent legislation called the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s desk. It quickly became popularly known as the “GI Bill of Rights.”

Have you wondered what “GI” stands for? In his book titled The GI Bill: The Law That Changed America, author Milton Greenberg describes it.

Dr. Greenberg

Milton Greenberg

“The term GI is an abbreviation for ‘government issue,’ which refers to the standardization of the military regulations or equipment (GI boots, for example). But it came to signify an enlisted person in any branch of service. Adding ‘Bill of Rights’ to the term combined two enormously powerful images.” 5,6

Mr. Montgomery

The 8th Army7 Air Corps Museum (“Mighty 8th Air Force”) in Georgia is just one of the many museums in America dedicated to the 15.6 million GIs, American soldiers, sailors, airmen, Marines, and Coast Guardsmen—including about 350,000 women—who served in our military during World War II.8

Under the broad guidance of John Stelle, former Governor of Illinois and a leader of The American Legion, the “GI Bill” concept was actually drafted by The American Legion’s Harry Colmery. While in Washington, D.C., Mr. Colmery wrote the draft in longhand in room 570 of the Mayflower Hotel. Some of the draft was written on hotel stationery.9 Mr. Colmery’s extensive drafts are now preserved under glass at The American Legion headquarters in Indianapolis.

Mr. Colmery knew from his own military service that ordinary Americans who serve in our military often do extraordinary things in service to their nation.

Harry Colmery and his drafts of the GI Bill concept.

Mr. Colmery did not want World War II veterans to stand in unemployment lines or sell apples on the street corners, as was all too often the case in 1918 after World War I.10 Indeed, he was determined not to allow poverty to define World War II veterans after the cessation of hostilities.11

Mr. Colmery

“… The burden of war falls on the citizen soldier who has gone forth, overnight to become the armored hope of humanity…. Never again, do we want to see the honor and glory of our nation fade to the extent that her ‘men of arms,’ with despondent heart and palsied limb, totter from door to door, bowing their untamed souls to the frozen bosom of reluctant charity, as we saw after the last war.”12

One of the principal legislative architects of the World War II GI Bill of Rights was Representative John Rankin (D-MS),13 and Chairman of the House Committee on World War Veterans’ Legislation.14

Michael Bennett, author of When Dreams Came True—The GI Bill and The Making of Modern America, had the following to say about Mr. Rankin, who also co-authored legislation creating the Tennessee Valley Authority and the Rural Electrification Authority.

Mr. Bennett

“Rankin was one of the most effective legislators in the history of the House; a master of parliamentary procedure; a brilliant, if vicious orator; a staunch proponent of public electrical power for the poor; and a defender of both servicemen/women and veterans, although not a veteran himself. He was not bashful about making himself heard.”15

John Rankin

Mr. Montgomery

Author Bennett also quoted Russell Whelan’s July 1944 article in the magazine The Nation, titled “Rankin of Mississippi:”

Mr. Bennett

“Rankin made more speeches devouring more minutes than anyone in Congress. When he was in full oratorical flight, a bony arm is thrust upward the skylight, the strands of the grey mop began to wave like reeds in a gale, and the chords of the Tupelo calliope [pronounced cal eye o pee] are tweaking every solar plexus in the place.16

“Rankin generally was a strong supporter of states’ rights but not when it came to a GI Bill and ‘the Federal government that these boys were representing on the battlefield.’17

“Although a supporter of segregation common in the South at the time, Rankin wanted ‘to protect the rights of smaller schools, including some Negro institutions.’18

“Indeed, when the American Council on Education initially opposed the GI Bill due to perceived, excessive federal control of education policy19 and other reasons, Rankin’s reaction was extreme. It transfigured him into a champion of unrestricted access to education—even for blacks.”20

Mr. Montgomery

Another prime mover of the bill in the House of Representatives was Republican Edith Rogers of Massachusetts, the ranking member of the Committee on World War Veterans’ Legislation (that Congress after World War II would rename as the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs).

During World War I, Mrs. Rogers traveled to Europe with the Women’s Overseas Service inspecting field hospitals. She authored the legislation creating the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps, later known as the Women’s Army Corps.21

Edith Rogers

The sixth woman elected to Congress, Mrs. Rogers served in the House from 1925 to 1960—35 years.

Her portrait, in which she was wearing her trademark rose, still hangs above the chairman’s seat in the subcommittee hearing room of the House Committee on Veterans’ Affairs.22

Mrs. Rogers took on the president of Harvard and others who portrayed the proposed GI Bill as a “special interest” of a lobbying group, The American Legion. Said Mrs. Rogers on the House floor…

Mrs. Rogers

“With reference to the educators calling The American Legion a powerful lobby, I think the American press is as strongly behind this measure as is the American public. It seems to me it is an all-over-the-country lobby.”23

Mr. Montgomery

Illustrative of some of the initial opposition in Congress to the GI Bill is the statement of Representative Dewey Short of Missouri:

Dewey Short

“Have we gone completely crazy? Have we lost all sense of proportion? How are you going to pay for this bill? You [members] think you are going to bribe the veteran and buy his vote, you who think you can win his support by coddling him and being a sob sister with a lot of silly, slushy sentimentality24 are going to have a sad awakening.”25

Mr. Montgomery

The “awakening” instead was a happy one. Notwithstanding the ultimate success of the World War II GI Bill in making the United States the first predominantly middle-class nation in the world,26 Milton Greenberg further summarizes the opposition to the bill…27

Dr. Greenberg

“Other veterans’ organizations [than The American Legion] dedicated to the disabled veterans feared that funds would be diverted from the most needy. Unions enjoying the protection of closed shops were cautious, and bankers feared government involvement in loans. And racial discrimination, legally commonplace at the time, including segregated military forces, became an issue regarding opportunities for black veterans.”

Mr. Montgomery

Students, we are focusing on the education and job training part of the WW II GI Bill because it represented economic empowerment. But the WW II GI Bill also included benefits to allow a veteran to receive medical care, vocational rehabilitation, loans for purchasing homes and starting small businesses, job placement, unemployment compensation, and other forms of assistance.28

Robert Maynard Hutchins, president of the University of Chicago, was one of the most vocal opponents of the World War II GI Bill legislation.

“Colleges and universities will find themselves converted into educational hobo jungles. … Education is not a device for coping with mass unemployment.”29

Mr. Hutchins

Robert M. Hutchins

Mr. Montgomery

As we will discuss in Chapter 3, Cloyd Marvin, a World War I veteran and president of George Washington University during World War II, and Selma Borchardt,30 president of the American Federation of Teachers, disagreed with Hutchins.31

Ernest McFarland

So did Senate Majority Leader Ernest McFarland (D-AZ) and Senate Finance Subcommittee Chairman Bennett Champ Clark (D-MI). Noted Senator Clark:32

Mr. Clark

“… The men and women who compose our armed forces not only hold the safety of our republic in their hands on the battlefronts today; they will hold its destiny for a generation to come….

Champ Clark

“By the time this war is over… more than 13,000,000 of our finest men and women will have seen service in our armed forces. They represent the cream of our human resources, the very backbone of our nation. This republic can ill afford to lose their skills and leadership.

“Yet that leadership and those skills have been rudely interrupted by war. Education has been halted, the men to whom we must look for the future of business, commerce, industry, and agriculture have been torn from their civilian posts….

“We must recapture those skills and that leadership…. I regard the GI Bill of Rights, passed by the Senate last week… as one of the most important measures that has ever come before Congress.”

Mr. Montgomery

Indeed, following fully 22 public hearings in the House33 and extensive debate, it took a midnight scamper back to the capitol by Representative John S. Gibson (D-GA) to break a 3-3 vote deadlock in a House-Senate Conference Committee on the proposed GI Bill.34

Folks, you may find interesting that some 40 years later it took a lot of hearings, too. From 1980 to 1987, the House of Representatives alone had 19 hearings on the legislation to create the New GI Bill that Congress later named the Montgomery GI Bill.

These 19 hearings from 1980 to 1987 included 12 by the Armed Services Subcommittee on Personnel and Compensation and seven by the Veterans’ Affairs Subcommittee on Education, Training, and Employment.”35 When signing the WW II GI Bill some two weeks after D-Day, President Roosevelt probably did not anticipate the GI Bill would become arguably “the most successful piece of domestic legislation since the Homestead Act of 1862.”36

President Franklin D. Roosevelt signs the GI Bill in 1944.

As he signed the original GI Bill in 1944, Roosevelt said the legislation…37

President Roosevelt

“[G]ave emphatic notice to the men and women of our armed forces that the American people do not intend to let them down.”38

Mr. Montgomery

How do you think soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines learned about the GI Bill in the midst of war?39

ONE SAILOR’S STORY

Let me share with you the thoughts expressed by James Michener, the American novelist. Mr. Michener wrote at age 86: 40

Mr. Michener

“In 1944, while the war was still raging and I was on a lonely island in the distant South Pacific, the Navy informed us that a remarkable law had just been passed by Congress to reward those who were fighting.

James Michener

“Its official title, the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, was rarely used because a popular simplification took over: the GI Bill.

“It said our nation, out of gratitude for the sacrifices being made by our men and women in arms, promised a free education, or assistance in finding a place in society when peace came, to every veteran.

“‘A free college degree!’ shouted the man who brought us the news.

“As a junior officer who saw thousands of military personnel in those years when I prowled the South Pacific, I saw the powerful effect41 this offer had on various types of men.

“My friend Joe told me: ‘I’ve always wanted to be a doctor,’ and became one. Another was tired of working for others and wanted a business education so that he could start his own small factory, and would get both.

“I decided to take my chances at being a writer.”

General Douglas MacArthur wades ashore during initial landings at Leyte, Philippines, October, 1944.

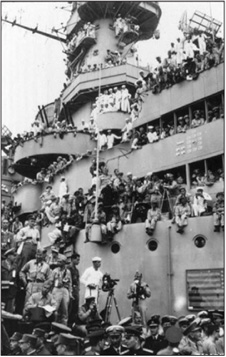

Aboard the USS Missouri as the Japanese formally surrender.

As the war neared conclusion, the GI Bill was there for the taking…42

All this at the very time that our sailors hung from every crevice of the USS Missouri to witness the Japanese surrender in Tokyo Bay…

The war was over. The sign below tells it all!43 The war was over for this guy in Times Square, too.

Families await their returning soldiers.

Celebrating war’s end in Times Square.

U.S. Cemetery, Cambridge, England.

The extent of selfless sacrifice was immense. As an example, 3, 812 officers and men from the 8th U.S. Army Air Corps alone are buried at Cambridge, England.44 Cambridge University donated the cemetery land on behalf of the British people.45

Folks, I want to take a few minutes now to describe for you—starting here and at the beginning of the next chapter—the profound effect the World War II GI Bill had on America.46

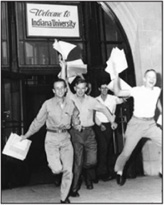

Veterans become students.

I think it is important for you to know the bill’s impact because, like Harry Colmery, I saw ordinary people do extraordinary things both during the war—while in combat—and after the war, in the classroom.

As Michael Bennett points out, the GI Bill’s “unintended consequences were even greater than its intended purposes;”47 veterans did not just pass through American higher education, they transformed it, as we’ll discuss shortly.48

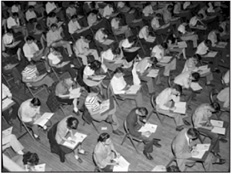

Of the 7.8 million veterans who used the GI Bill, 2.23 million attended colleges; 3.48 million attended other schools such as trade schools, business schools, and high schools; 1.4 million participated in on-job training; and 690,000 received institutional on-farm training.49

The results?

According to the Veterans Administration, the World War II GI Bill produced 2, 600,000 skilled tradesmen and women, 1, 375,500 businessmen and women, 451,000 engineers, 238, 240 teachers, 175,000 scientists, 66,000 doctors, 22,000 dentists, and 12,000 nurses.50

What do you think, class? Pretty impressive, no?

Author Milt Greenberg notes at least 10 Nobel Prize winners were former GIs.51

Dr. Greenberg

“About 50 percent of the engineers who worked for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) were veterans and I think many of whom, without the GI Bill, would not otherwise have gone to college.

“Spurred by wartime applications of science and technology, college-educated GIs contributed to a scientific revolution in television, computers, civil engineering, medicine, chemistry, physics, space exploration, and a continuing tradition of invention.”52

Mr. Montgomery

Many of these individuals were the first in their families53 to graduate from college or formal technical training. The Veterans Administration and the colleges/training institutions provided the opportunity, and the veterans provided the initiative—what Michael Bennett called “the American creed in action.”54 In 2000, Anthony Principi looked back, especially with respect to those who were enrolled in college-level training…

Mr. Principi

“Veterans excelled in the classroom, ran the student governments, challenged professors, refused to wear freshman ‘beanies,’ began raising families, and some veterans did something that was seen as rather unusual—they went to school year ‘round.”55

Anthony Principi (right) joins President George W. Bush (center) during a Washington ceremony honoring veterans.

Mr. Montgomery

I think these veterans at the University of Nebraska are good examples of the initiative Secretary Principi refers to. This was the case all across America.

World War II veterans flocked to schools like the University of Nebraska, taking pre-entry tests (left) and eventually registering for classes (below).

Sonny’s Lessons Learned

Students, you’ll hear a lot about unintended, negative consequences of laws and lawmaking; phrases like “those were not the results we [Congress] had in mind” or “instead of fixing it, Congress has created more problems.”

Despite the best efforts of our elected representatives, unintended consequences do occur.56 I think they most often occur when legislation addresses “symptoms” of problems—rather than the problems themselves.

But unintended consequences can be positive! I think author Michael Bennett best made this point: “The World War II GI Bill’s unintended consequences exceeded its intended purposes.” No one expected 7.8 million veterans to enroll in college and other forms of training, benefiting themselves and society alike.

The stated purpose of the World War II GI Bill was not to create a “learned society” or a “knowledge generation.” Its purpose was simply to help millions of ex-GIs transition to civilian life after the war, avoiding serious unemployment.

WHAT’S NEXT

In the next chapter, we’ll discuss the continued, unanticipated success of the World War II GI Bill of Rights, a law that worked beyond expectation.