Robert C. DeCamara, Reporter

Adell Crowe, Reporter, USA Today

Richard Halloran, Reporter, New York Times

Lieutenant General Robert Elton, U.S. Army

George C. Wilson, Reporter, Washington Post

P.J. Budahn, Reporter, Army Times

Otto Kreisher, Reporter, Copley News Service

Tim Carrington, Reporter, Wall Street Journal

Honorable Bob Stump (R-AZ),

Committee on Armed Services, 2001

Also featured in this chapter:

Paul Smith, Reporter, Army Times

SONNY’S SUMMARY

Just six months into the three-year test of the New GI Bill, limited to service members entering military service between July 1, 1985, and June 30, 1988, 70 percent of Army enlistees signed up for this new education benefit. Almost four times as many enlistees signed up for the New GI Bill in its first year than for VEAP in its first year. We also won two hard-fought battles we didn’t expect to fight, especially with the test program going so well: (1) an OMB-proposed economic measure to repeal the statutory test program and return to the inferior VEAP program, and (2) a proposal from within my own party to reinstate the draft and discontinue our All-Volunteer Force.

Mr. Montgomery

President Reagan signed the three-year New GI Bill program into law (Public Law 98-525) on October 19, 1984, and it took effect July 1, 1985. On June 24, 1985, I sent a letter to each of the 435 members of the House of Representatives describing the program and its many advantages for the nation.1

During the ramp-up period in early 1985 when the service branches began developing information and brochures to publicize and explain the New GI Bill, we learned of a small issue. Some of the information packets the service branches produced referred to “veterans’ education benefits” rather than the “New GI Bill.”2 Some argued the differences in the words produced a distinction without a difference. But we saw a big difference.3

My colleagues and I felt the words “GI Bill” promoted a well-known, powerful image and represented a program revered by many Americans due to its unqualified earlier successes.4

So, we simply worked informally—over many months—with officials of the Department of Defense and each service branch.5 Each ultimately adopted the words “New GI Bill.”

Folks, let me make two observations about the way we resolved this matter.

The first is that if we take care of the little things, the big things tend to take care of themselves.

I believe resolving the small semantic issue about what to call the program made a difference in how youth, parents, guidance counselors, and media received the New GI Bill. The GI Bill already had name recognition in America’s heritage.

Ask an adult in America to name one government program that has worked and I suspect many will mention the World War II GI Bill.

The second observation is that most problems are more easily resolved with honey rather than vinegar. I’d say the vinegar approach is represented in a nutshell by the wry Washington phrase some of you may have heard: “Grab them by their budgets; their hearts and minds will follow!”

In my experience, this saying generally refers to Legislative Branch oversight of the Executive Branch and the inherent power of Congress in deciding the dollar amounts to be appropriated to federal departments and agencies. Only Congress can appropriate money.

There was no reason to beat up the service branches by formally directing them, for example, through Appropriations Committee “report language”6 accompanying an annual DoD spending bill to use the words “New GI Bill” rather than “veterans’ education benefits” in recruiting literature. Instead, we resolved this small matter informally through direct, non-threatening discussion. Another saying I think works to describe an approach to problem solving is “use a scalpel, not a meat ax.” I’ve found this approach helpful. Isolate the problem, then fix it!

The three-year New GI Bill program went forward as planned on July 1, 1985, but it was difficult to get the media to focus on it. Notes reporter Robert C. DeCamara:7

Mr. DeCamara

Robert DeCamara

“Young people can obtain all the money they require for college.

“Uncle Sam will give it to them—tens of thousand of dollars per individual. It isn’t a loan, it doesn’t have to be repaid, and it isn’t based on need.

“Last fall without fanfare, Congress established a generous student-aid program along those lines, effective the beginning of this month.

“If you’re unfamiliar with it, that’s understandable. The media have ignored it. In all the debate over federal grants and loans for students in post secondary schools, it’s never mentioned. It’s the mystery education subsidy, a darker secret (what is not?) than a CIA covert operation. “It’s called The New GI Bill and the Army College Fund.8

“All the military branches got the improved version of the GI Bill on July 1, but only the Army has a college fund, too, which makes its aid package easily the most lucrative. The sums involved are substantial—$10, 800 from the GI Bill and $14, 400 from the Army College Fund—for a combined pay-out of $25,200 for a four-year enlistment.

“That kind of money will buy a bachelor’s degree at many institutions, according to The Chronicle of Higher Education. The authoritative trade journal puts the average annual cost of tuition, room, and board at a bargain at $3, 381 at public universities, a steeper $7, 635 at private schools.

“… No youngster willing to serve his country for two to four years need go without a college education for lack of money. That’s a quiet achievement of which Americans can be proud.”

Mr. Montgomery

Here’s how Adell Crowe of USA Today reported service member interest during the New GI Bill initial implementation:

Ms. Crowe

Adell Crowe

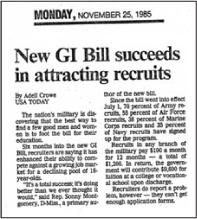

“Just six months into the New GI Bill, the program was doing better than we ever thought it would. Seventy percent of Army enlistees, 55 percent of Air Force enlistees, 38 percent of Marine Corps enlistees, and 35 percent of Navy recruits have signed up for the program.”9

Mr. Montgomery

The New GI Bill proved financially more attractive than the post-Vietnam era Veterans’ Educational Assistance Program, known as VEAP, that Congress initiated in 1977. We designed the New GI Bill that way. We intended it to be more financially attractive.

Under VEAP, the service member could contribute up to $2,700 and the VA would match it at $5,400, for a total of $8,100—a ratio of three-to-one.

Under the New GI Bill, the service member would put in $1,200 (the House-passed bill did not contain this provision) and would receive $10,800,10 a ratio of nine-to-one.

By percentage, almost four times as many enlistees signed up for the New GI Bill in its first year than did so for VEAP in its first year.11 For the Air Force and Marine Corps, the sign-up rate was even greater. Plus, VEAP was not easy to administer, given the process of service members putting money into the account and then taking it out, thus changing the government’s contributory match.

As I see it, those of us in Congress did not do a good job designing VEAP. Noted former Secretary of the Army John Marsh, “VEAP was like the Articles of Confederation. It wasn’t the answer.”12

We did our best to make the New GI Bill both easy to use and easy to understand.

During January 13-15, 1986, I headed a delegation of the House Veterans’ Affairs Committee to visit basic training sites for each service branch.13 With the three-year New GI Bill program now under way, the delegation wanted to learn what enlistees had to say about it.

We visited the Basic Training Center, Lackland Air Force Base, San Antonio, TX; Naval Training Center, San Diego, CA; Marine Corps Recruit Depot, San Diego, CA; and Army Air Defense Artillery Center, Ft. Bliss, TX.

We attended the orientation each service branch gave to new enlistees on the New GI Bill program. Based on this orientation, recruits would then decide whether to have $100 per month deducted from their pay for 12 months in order to receive $10, 800 in New GI Bill benefits.

I found talking directly with new soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines gratifying and informative. We designed the New GI Bill specifically for them. It was important to get away from Washington and learn from the service members themselves how we were doing.

By this time, some six years after our informal team in 1980 first got a gleam in our eye about a permanent GI Bill to encourage quality men and women to enlist—instead of drafting them—journalists started taking an interest in our vision.

Noted writer Richard Halloran of the New York Times:

Mr. Halloran

Richard Halloran

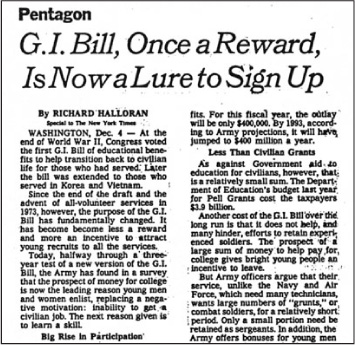

“Today [December 5, 1986], halfway through a three-year test of a new version of the GI Bill, the Army has found in a survey that the prospect of money for college is now the leading reason young men and women enlist, replacing a negative motivation: inability to get a civilian job. The next reason given is to learn a skill.”14

Mr. Montgomery

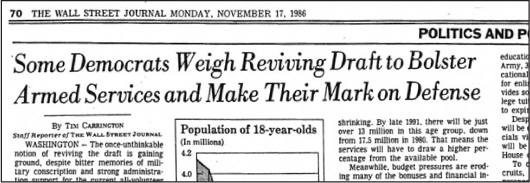

One factor in our vision for a strong educational incentive for three or four years of service was the objective fact that the supply of potential recruits was dwindling, but the need or demand for such enlistees was undiminished.

As I’ve noted, many of my Veterans’ Affairs Committee colleagues and I also served on the Armed Services Committee.

So we knew the pool of young men and women from which our service branches would have to recruit would decline by 20 percent between 1982 and 1987.15

By 1991, there would be just over 12 million young adults in the relevant age group, down from 17.5 million in 1980.16 This meant the service branches would have to draw a higher percentage of the available pool. According to economist Sharon Cohany writing in the Bureau of Labor Statistics Monthly Labor Review in October 1986, in an article titled “What Happened to the High School Class of 1985,” “the proportion of high school seniors going on to college… reached a record 58 percent in 1985.”

To cope with the decline in eligible recruits, the Army planned to contact more prospects between the ages of 20 and 26. One group to focus on was college drop-outs. Noted Lieutenant General Bob Elton, deputy chief of staff of the Army:

Lt. Gen. Elton

Bob Elton

“Forty percent of Americans drop out of college the first year; maybe we ought to be there for them.”17

Mr. Montgomery

As you learned earlier, by law the New GI Bill test program ran from July 1, 1985, to July 1, 1988, to see if it would help with recruiting. Two separate problems emerged almost immediately.

In early 1986 the first problem emerged.

The ink was barely dry on the New GI Bill program when the Defense Department officially notified Congress that, as an economic measure, it would propose legislation to abandon the test program and return to VEAP.18

I had both an analysis and public testimony from the General Accounting Office concluding “the New GI Bill has strengthened Army recruiting” and “recruits were signing up for the New GI Bill at a far greater rate than they did for VEAP.”19

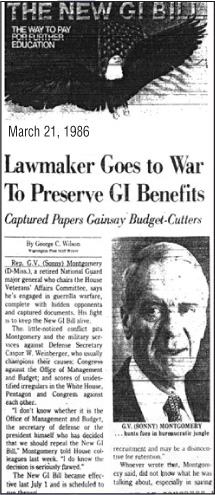

I also obtained a pile of Pentagon documents that buttressed my argument. George C. Wilson quoted some of these documents in the March 21, 1986, Washington Post.20

Here is what each service branch said in internal documents, as reported by Mr. Wilson:21

Mr. Wilson

George C. Wilson

Army: “Switching back to VEAP after completing the costly conversion to and implementation of the New GI Bill will… cause damage to the recruiting program in general and to the Army’s educational incentive programs in particular.”

Navy: “Secretary John F. Lehman, Jr., in recent testimony before the House Armed Services Committee, said of the New GI Bill, ‘it is a great program, and you are to be congratulated on it.’” Air Force: “An internal memo said suspension of the New GI Bill would have ‘serious impact’ on recruiting quality people and ‘would send a clear signal to the youth population that [the military] services do not care about their educational development.22 Request that the New GI Bill be permitted to continue though the life of its originally legislated three-year period.’”

Mr. Montgomery

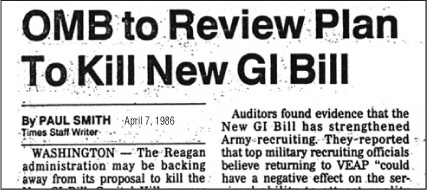

By June 1986 we had won the skirmish. Here’s what two Army Times reporters wrote—Paul Smith on April 7, and P. J. Budahn on June 9:

Mr. Smith

“The Reagan Administration may be backing away from its proposal to kill the New GI Bill, Capitol Hill sources say.

“Although the Administration announced plans earlier in the year to cancel the three-year test program, no request for legislation to do so has been sent to Congress, a staff member said.

“James Miller, director of the White House’s Office of Management and Budget, whose office first proposed the cancellation, had promised to review the proposal.”23

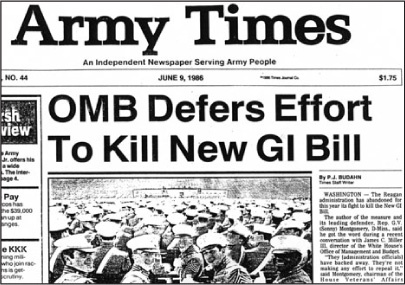

Mr. Budahn

P.J. Budahn

“The Reagan Administration has abandoned for this year its fight to kill the New GI Bill.”24

Ladies and gentlemen, my colleagues and I won the March to June 198625 scrap to keep the New GI Bill moving forward.

I’d like to tell you why I believe the service branches and I were correct on this issue. Here’s part of what I said in a letter to Barry Goldwater of Arizona, then-chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee:26

“The National Guard and Reserves are already offsetting the cost of the [New GI Bill] program through increased retention. Re-enlistments for our Reserve components have increased 20 percent over the last year through the GI Bill. That amounts to savings of $50,000 per individual in reduced training costs in the Air Guard.

“Also, in the Reserves, the sign-up is now for six years instead of three years, which will produce great savings in the training cycle.

“… Recruits are signing up in great numbers for the educational benefits offered by the GI Bill. As a result, I think we can reduce the large bonuses now being paid to recruit young men and women into the service….”

The second problem emerged in November of 1986 when we had to debate with some of my fellow Democrats who wanted to revive the draft. In fact, I, too, had sponsored a bill for several years that would have reinstated the draft.

But I dropped it because the country had no appetite for it. I believe military service of two or three years is an obligation of citizenship. But Congress would not support the bill to reinstate the draft unless the Soviets were landing on the eastern shore of Maryland!27

Nevertheless, back in February 1985, Senator Fritz Hollings (D-NC)—an advocate going back to 1979 for a New GI Bill—and Senator Steve Simms (R-ID), introduced a bill to revive the draft.28 Further, in October 1984, our Army General Bernard Rogers, commander of the North American Treaty Organization forces in Europe, also called for a universal draft.29

Let’s hear some of the highlights from reports by Otto Kreisher, Copley News Service,30 and Tim Carrington of the Wall Street Journal.31

Mr. Kreisher

Otto Kreisher

“As the bitter memory of Vietnam fades, some Democratic members of Congress and even a few military leaders32 are beginning to talk about a subject long considered politically unmentionable—restoration of the draft.”

“… faced with population projections showing a sharp decline in military age males over the next decade and with prospects that continuing budget deficits will force constraints on military pay and other compensation, [some Democratic] officials are searching for an alternative to the current All-Volunteer Force (AVF).”

Mr. Carrington

Tim Carrington

“The once unthinkable notion of reviving the draft is gaining ground, despite bitter memories of military conscription and [Reagan] administration support for the current All-Volunteer Force.

“Some Democrats [Senators Sam Nunn and Gary Hart] are looking to put their imprint on the national security policy. But that is only one reason why some form of national conscription is again being talked about. A combination of demographics and economics—fewer young people and skimpier federal budgets to support current bonus and recruitment programs—may create a shortage of soldiers by the 1990s. And some critics of the all-volunteer armed forces say a draft would be more equitable.”

Mr. Montgomery

Indeed, in the Carrington article Senator Nunn said, “It was a mistake to abolish the draft.”33

But Congress did not reinstate the draft, even though military service is the most fundamental and longstanding form of service to the nation. Years later, however, Congress created a voluntary program of civilian—not military—national service called AmeriCorps, which President Clinton signed into law in 1993.34

Steven Waldman wrote a book about how AmeriCorps became law. He called it The Bill: How the Adventures of Clinton’s National Service Bill Reveal What Is Corrupt, Comic, Cynical—And Noble—About Washington.35

Folks, Mr. Waldman’s book reveals how one of my best friends, Representative Bob Stump (R-AZ), and I joined forces to ensure that the post-service educational benefit of AmeriCorps volunteers did not exceed the educational benefit paid to the men and women serving in our all-volunteer military. We both believed our service members incur greater personal risks.

That said, persons who serve America through AmeriCorps and similar programs earn their post-service education benefit, too. I respect that. Conversely, we provide billions in financial aid for other deserving individuals who nevertheless do not serve their nation.

Why serve when financial aid abounds for those who do not serve?36

As I see it, military service goes back to colonial America.37 The National Guard, for example, conducted its first training drill on the village green in Salem, MA, in 1636.38

In any case, I considered it a personal honor that Rep. Stump succeeded me as chairman of the Veterans’ Affairs Committee for six years when the Republican Party won a majority in the November 1994 Congressional elections.

Bob then went on to chair the Armed Services Committee prior to his retirement in 2002. Bob passed away in June 2003.

Like so many young Americans during World War II, Bob Stump was unabashedly less than fully open about his age when he enlisted in our military.

Bob served near Iwo Jima as a Navy corpsman/combat medic at age 16. In Iwo Jima, our Marines suffered 26,000 casualties,39 including 6,800 who died fighting the Japanese Army in taking the island. As Americans, if we ever wondered about the price our fellow citizens have paid for our every day freedoms, Iwo Jima provides one of the answers.

However flattering, I don’t think Bob would say he was part of the “greatest generation,” a term first coined by Tom Brokaw.

I think he’d say that as a teen he was proud to do his part to serve America. And I think he’d also say we should not assume the world is a safe place.

On September 11, 2001, when we learned that extremists were commandeering U.S. commercial airliners to harm us, one member of Congress refused to evacuate his office in the Capitol complex when the Capitol Police came to get him. That was Bob Stump of the House Armed Services Committee. Noted Chairman Stump at the time:

Mr. Stump

Bob Stump

“Hell’s fire, I’m staying here. This is my duty station. Whoever is responsible for these bombings can’t make me leave.”40

Mr. Montgomery

And he didn’t.41

In closing this chapter, I’d note that we nevertheless achieved a major legislative victory in 1986 working principally with the National Association of State Approving Agencies and Alan Cranston and Bill Cohen in the U.S. Senate. In Public Law 99-576, enacted on October 28, Congress made on-job training and apprenticeship an eligible program for usage under the 1985-1988 New GI Bill program that, at this point, had become know unofficially as the three-year test program.42

Sonny was recognized by many organizations and received many special awards, including this unique lobster from the National Association of State Approving Agencies.

Congressional oversight of executive branch implementation of law is both legitimate and important.

An oversight example from this chapter is the initial service branch brochures to publicize and explain the New GI Bill using the words “veteran’s education benefits” rather than “New GI Bill.” The words “GI Bill” historically have promoted a powerful image with parents, guidance counselors, and the American public. So we asked the service branches to use “New GI Bill” in their promotional materials. They agreed to do so. I believe it made a positive difference in how the test program was received.

WHAT’S NEXT

Let’s travel the legislative road in the House and Senate Veterans’ Affairs Committees that leads to enactment of the Montgomery GI Bill in 1987. At times it was a bumpy one.