The adoption of the two-year law in France in 1905, which also involved conscripting everyone physically capable of serving, led to significant growth in the French order of battle, including an increase to twenty-two corps and the assignment of a reserve infantry brigade to most of the corps. There were also twelve reserve divisions available for the field army. These troop increases, plus the prospect of British participation in a war with Germany, led to the adoption of a much more confident Plan XVI in 1909. The plan provided for five armies to deploy on line from the east of Reims in the north to Belfort in the south, backed up by a reserve army of four corps behind Verdun.22 As Greiner noted, this concentrated ten corps on the front line opposite Lorraine with an army of two corps on each flank. The French now also had ten deployment railway lines available instead of nine.

The Balkans was beginning to have a major negative effect on Austria’s military position and, by extension, that of Germany as well.23 The Austrian annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina on 6 October 1908 ignited outrage in Serbia, Macedonia, Turkey and Russia. Serbia demanded territorial and economic compensation, and was supported by Russia. A special intelligence estimate was written for the crisis period for 1908/09, which made express reference to the fact that Serbia’s internal instability was a destabilising factor in Balkan politics. In November 1908 the Austrians began a gradual partial mobilisation in Bosnia, bringing the force there to seventy-eight battalions (about three corps) with the two neighbouring corps also being reinforced. ‘At the end of March [1909] the peace of Europe was seriously threatened’, the annual report said. ‘It was doubtful that the expected war between Austria and Serbia could have been localised, because Russia’s relationship with Serbia encouraged it to continually increase its demands.’

Plan XVI (1909)

The intelligence estimates said the war was averted only because the Russians were not ready to fight, and because the Russians also recognised that, in a Russo-Austrian war, Germany would support Austria. The Russians told the Serbs to drop their objections to the Austrian annexation of Bosnia, and on 30 March 1909 the Serbs did so, promising to demobilise, renounce claims to Bosnia and otherwise behave in a good neighbourly manner. The intelligence estimate characterised this as a victory for Austro-German diplomacy. The Italians, however, had been very reserved. Indeed, if it had come to hostilities, the Austrians expected to find the Italians in the enemy camp.

The Balkan crisis of 1908/09 had a major effect on German war planning. ‘Germany must now be prepared for a war with France or Russia as well as a war against both, which Britain can also join.’ The war might begin in the Balkans as a one-front war, which would quickly develop into a two-front war and Britain could join any war against Germany. The war plan was therefore changed to provide for a war that started in the west – Aufmarsch I – or that started in the east – Aufmarsch II, also called Grosser Ostaufmarsch, the great deployment to the east.

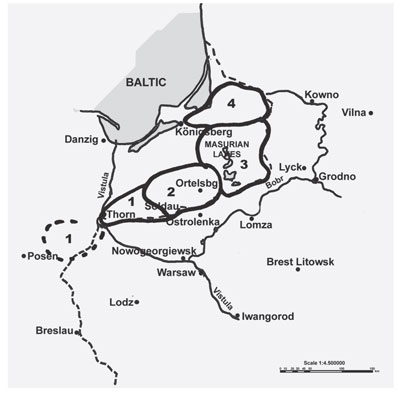

There were twelve original documents available from the 1909/10 war plan: the mobilisation schedule; covering force maps for the east and west; instructions for the Aufmarsch I and II covering forces; orders of battle for Aufmarsch I West, I Ost, II West und Ost and for the Nordarmee (North Army); and Aufmarschanweisungen for Aufmärsche I West, I Ost, II West and II Ost. This was summarised in thirteen typewritten pages (with handwritten annotations), a handwritten force structure table and a map of the Aufmarsch II Ost deployment (1:4,500,000).

The plan noted that mobilisation meant full general mobilisation; due to the interconnected nature of mobilisation, a partial mobilisation was impossible.

The plan stated that the degree of support Austria and Italy would provide was dependent on the political situation. But it also said that the arrival of the Italian army could not be counted on.

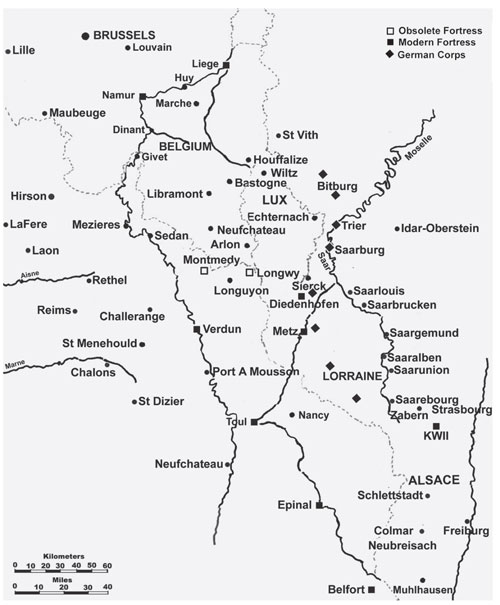

The total German force was now seventy-three divisions strong. IX RK was still assigned to provide coastal defence in north Germany. In Aufmarsch I, a one-front war in the west, the strength and missions of the 1st and 2nd Armies are unchanged. The 2nd Army would receive general staff officers who had reconnoitred the routes and would serve as guides of the attack columns for the coup de main against Liège. The 3rd Army area of operations was extended south to the middle of Luxembourg. The 4th Army, with an additional corps and reserve corps, had its zone of operations extended south to cover the rest of Luxembourg. The 5th Army was now at Metz–Diedenhofen; the 6th Army, with three corps and a reserve corps, assumed the 7th Army’s mission in Lorraine; and the 7th Army was pulled back to Strasbourg.

1909/10 West I

It is possible that the enemy will attack with strong forces from Belfort and across the Vosges into the upper Alsace, while at the same time advancing on Fortress Kaiser Wilhelm II. Initially, the 7th Army will be held back to cover the upper Alsace, to be committed on the left flank of the 6th Army, or to be transported by rail to another theatre of operations.

The Schlieffen School contended that Moltke was strengthening the left wing, which demonstrated that he did not understand the Schlieffen plan. In fact, it is evident that, given a worsening strategic situation, including Italian unreliability, Moltke had created the 7th Army to guard Alsace and act as a reserve.

The old Aufmarsch II was now called Aufmarsch Ia. Ten divisions were deployed in the east, sixty-one in the west. In order to form the eastern army, a corps and a reserve corps were detached from the 1st Army, a corps and a reserve division from the 2nd, a corps from the 3rd and two reserve corps from the 5th.

1909/10 Ost II

The new Aufmarsch II is a Grosser Ostaufmarsch, a massive deployment to East Prussia which is clearly modelled after Schlieffen’s Aufmärsche of 1900/01 and 1901/02, but with more emphasis on the offensive and less on Schlieffen’s counter-attack.24 It was surely written for a Balkan crisis, a war between Russia and Austria, with Germany assisting Austria and the French initially neutral. Forty-two divisions would deploy to the east. The 1st Army, with two corps and two reserve corps, had to deploy by rail to the left (west) bank of the Vistula and then foot-march about 100km to the west of Soldau. From there it would attack towards Warsaw. The 2nd Army (four corps, two reserve corps) would attack towards Lomza, though an attack on the heavily fortified town itself was considered ‘hopeless’. The 3rd Army (five corps, two reserve corps) would attack towards the Niemen between Grodno and Kowno, principally to fix the Russian forces there in place; the 4th Army (four corps, two reserve corps) would outflank the Niemen line to the north of Vilna.

This would have been a slow-motion deployment using only two or three double-tracked railway lines (in 1914 the German west front deployment used thirteen double-tracked railway lines). Marching the 1st Army 100km would have taken five days. Deploying the 3rd and 4th Armies, with a total of thirteen corps, would have taken weeks. The (unstated) problem of the Ostaufmarsch was that, slow as the Russian deployment might be compared to the German deployment in the west, the Russian deployment was faster than the German Ostaufmarsch deployment.

1909/10 West II

Twenty-nine divisions would remain in their garrisons. When the French mobilised, these units would move by rail-march and attack. Initially, the German forces which had already begun or completed their mobilisation would have a head start over the French, and if possible would use this advantage to attack. This operation was known as Aufmarsch IIa. The 5th Army, with four corps and three reserve corps, would deploy between Metz and Bitburg; the 6th Army, with the three Bavarian corps and reserve corps, would deploy behind the Saar north of Saargemünd; and the 7th Army, with four corps and a reserve corps, was spread out from Saarburg to the upper Rhine.

No single part of the Schlieffen plan myth has been the subject of as much error and contradiction as the Grosser Ostaufmarsch.

Gerhard Ritter claimed that the elder Moltke had recognised in the 1870s and ’80s that he could not win a war against France and therefore developed Grosser Ostaufmarsch to attack Russia while defending in the west.25 Instead of relying on the elder Moltke’s brilliant plan for attacking in the east, Schlieffen discarded the Grosser Ostaufmarsch in favour of the Schlieffen plan. In August 1914 a Grosser Ostaufmarsch would have allowed Germany to respect Belgian neutrality. Britain would therefore have had no cause to enter the war, and the result would have been a negotiated peace in which Germany could have expanded east.

In fact, as shown in Inventing the Schlieffen Plan, the elder Moltke himself was forced to discard the plan for an offensive in the east in 1888: the German army was simply not strong enough for such an operation.26 It was Schlieffen who revived the Grosser Ostaufmarsch in 1900/01 and 1901/02, but as part of his counter-attack doctrine.

It has also been contended, with a considerable lack of consistency, that it was the younger Moltke who cancelled the elder Moltke’s Grosser Ostaufmarsch in 1913 in order to rely solely on the Schlieffen plan. This supposedly proves that Moltke had an offensive war plan in the west; according to this argument, an offensive concentration in the east was, for reasons that are not clear, morally superior to one in the west.

This argument is self-contradictory. If the perfect Schlieffen plan was the sole war plan, how could there have been a plan for a Grosser Ostaufmarsch too? In fact, we now see that the younger Moltke revived the Grosser Ostaufmarsch in 1909/10, this time in the expectation of a war that would begin as a one-front war in the east.

According to the myth, Schlieffen bequeathed the Schlieffen plan, the sole and ‘perfect’ plan, to the younger Moltke. The 1909/10 Aufmarschanweisungen show that this is utter nonsense. Moltke modified his planning to meet the changing military and political situation, in particular, Russian military recovery and political tension in the Balkans: ‘keeping the right wing strong’ was hardly the only issue the younger Moltke had to deal with. This meant that in the 1909/10 mobilisation year Moltke did not just have the ‘perfect’ Schlieffen plan, but four plans: Aufmarsch I was for a one-front war in the west; Aufmarsch Ia for the most likely circumstance, a simultaneous two-front war; Aufmarsch II (Grosser Ostaufmarsch) for a war that grew out of a Balkan crisis; and Aufmarsch IIa for French intervention in the east front war.

The German deployment in the 1909 Schlussaufgabe was an Ostaufmarsch: the German army in the west contained only twenty-three divisions, so the French were ‘massively superior’.27 The 1st Army was in Lorraine with three corps; the 2nd Army was on the east bank of the Rhine defending southern Germany with three corps; the 3rd Army with five and a half corps was in reserve on the Saar. The French attacked with the mass of their forces (eight to eleven corps) in Lorraine, supported by an attack with an army to the north of Diedenhofen and another with about six corps in Alsace. Groener took part in this exercise.

Moltke said that in the next war the Germans were going to be severely outnumbered and they were not going to be given any easy problems to solve. The French also had their difficulties, as their armies were divided into three parts by Metz–Diedenhofen and the Vosges–Strasbourg. The Germans, therefore, had to attack and strike at the heart of the French army before the French had a chance to unite their force: partial success would not be adequate.

A German counter-attack into Alsace was out of the question. The Germans would not be able to mass a significant force there. In addition, it was completely immaterial to the Germans whether the French could cross the Rhine into Baden. Except for a few Landwehr brigades, the Germans could have pulled all their troops out of Alsace.

A counter-attack against the French army in Luxembourg had attractive advantages. However, in the current situation the Germans could not turn the French left in time. A German frontal attack in Luxembourg would accomplish nothing, because at the same time the French main body would drive the Germans out of Lorraine.

Only victory over the French main army in Lorraine would be decisive. The Germans had eight corps for the decisive battle in Lorraine, and would certainly not be numerically superior to the eight to eleven French corps there. There would be four ways to attack the French: frontally, on their eastern (right) flank, on the western (left) flank or both flanks.

Moltke said that a frontal attack would merely drive the French directly to the rear. The Japanese had pushed the Russians back in Manchuria with frontal attacks with little result. At the same time, the French army in Luxembourg would cross the Moselle in the German rear and the campaign would end in disaster for the Germans. The German deployment did not permit a strong attack on the French right. Neither, with only eight corps, could the Germans conduct a double envelopment. The only possible solution was an attack from Metz against the French left. The Germans had to be conscious of the fact that the French would recognise the threat to their left and would be very strong there. Tactically this would be a frontal attack. The Germans would be faced with successive French defensive positions and fresh French forces. The operation might drag on, a situation the Germans could not tolerate. The German army needed quick, decisive victories.

But this attack had the advantage that it would be directed against the strategic flank of the enemy army, and that was the most important thing. The area to the south-east of Metz was the most sensitive point in the entire French operation. A victory here must have decisive results. Moltke said that the majority of the officers had come to this conclusion, but that most had not been ruthless enough in its application. Many expected that if the Germans withdrew to the east, the French main body would follow and so present a flank to attack. Moltke said there was no reason why the French would make such an obvious mistake. It was better to stick with the principle that the enemy would act in the most effective manner possible.28

A surprise attack could only be launched through Fortress Metz. This attack should be conducted using the entire 3rd Army, supported by all of Metz’s available guns and troops. The French could not fall back, but would have to stand and fight to defend their flank, and it would be likely that the Germans would push in the French flank. At the same time, the German 1st Army would occupy a defensive position behind the Nied with the left flank on the Saar, south of Saargemünd. Moltke noted that this operation was risky, but that it was impossible to defeat an enemy that was twice the German army’s strength without taking risks. This operational problem is important in understanding Moltke’s concept for the defence of Lorraine in 1914.

The Russian political class was judged to be solidly anti-German: Germany got no thanks for supporting Russia during the Manchurian War.

Finland was in a pre-revolutionary state, but in general, Russian political stability had advanced to the degree that, in case of mobilisation, only one division would remain in Moscow to maintain security, instead of the previous two divisions.

Russian troop strength was unchanged from 1908: 47,750 officers and 1,297,000 men (in 1908 the German army consisted of 613,333 officers and men). The annual army conscript class was 432,539 men; the German conscript class was around 250,000.29 These numbers were enough to give any German war planner pause for thought. The Russian peacetime army was twice as large as the German. Each year, the Russians trained 180,000 more men than the Germans did, which meant that each year the Russians gained 180,000 more reservists – the equivalent of about five reserve corps.

The Russian army still had not recovered completely from the Manchurian War. It suffered from a shortage of infantry officers and of NCOs of all branches. At the beginning of the year, twenty-three battalions and sixty-six cavalry squadrons were on internal security duty. This was reduced by the end of the year to eight battalions and fifteen Cossack sotnia in the military district of Warsaw. Losses of clothing and equipment in the Manchurian War still had not been fully replaced. Practice mobilisations had been introduced, with good results. Marksmanship training was still poor, due in most part to a lack of garrison firing ranges.

In a war with Germany and Austria, Russia would employ fifty-six divisions, as opposed to sixty divisions in 1907. This is probably because the Germans thought that fifteen divisions (nine active, six reserve) would remain in Siberia, their peacetime stations. The intelligence estimate said that if Russia became involved in a war on her western border, then Japan would attack in Manchuria. This was the reason why the Russians were planning to redeploy units from Poland to the interior of Russia, and the basis of rumours that the Russians had adopted a defensive war plan on its western border. The new Russian deployment line would probably be Rowno–Kowel–Brest-Litovsk–Kowno. The conclusion drawn was that the Russians had little offensive power in a war against Germany and Austria. (The 1909/10 Aufmarsch plan said that according to the Austrian intelligence estimate, the Russian army would deploy fifty-two divisions against Austria and Germany, the same number as in 1902; that is to say, the Russians had reached the same high level of readiness that they had attained before the Japanese War.)

The Germans had drawn the wrong conclusions from the rumours of the pending Russian reorganisation. Japan had nothing to do with it. The Russians were planning to pull back units from Poland to the interior in order to co-locate them with their recruiting districts, where their reservists lived, which would speed up mobilisation. They also intended to reduce their fortress garrisons, as the Germans suspected, in order to create additional manoeuvre units. The Russian goal was not to adopt a defensive strategy, but to be able to assume the offensive faster and with greater force.

The Germans were not impressed by the new Russian tactical doctrine. The Russians seemed to have introduced a standard infantry attack procedure (Normalangriff) which did not give any consideration to the terrain and situation. It prescribed early deployment from column into a line and what the Germans felt was excessive dispersion, and displayed too much concern with utilising cover, with the advance by small groups and individuals being too slow and inadequately supported by fire. Cavalry battlefield reconnaissance was insufficient. Russian artillery took up covered positions at long ranges and stayed there for the course of the engagement. Because of the poor horse teams and heavy guns, the Russian artillery was not very mobile in any case. In each particular, the Russian stereotyped offensive tactical doctrine was the antithesis of flexible German doctrine, and the conclusion the Germans must have drawn was that a Russian attack would not be effective.

In 1909 the Russian army made several further improvements. Combined-arms live-fire exercises were reintroduced. Large-scale field training exercises now practised meeting engagements. Reservists were again being recalled to the colours for training. The state of discipline had improved. Russian artillery range firing was better than that of the infantry or cavalry. The field artillery, to include reserve and replacement units, had been completely re-equipped with fast-firing guns. In spite of revolutionary propaganda, especially in Polish regiments, there was no sign of serious indiscipline, much less mutinies. Rail construction still focused on the east; little was being done in the west.

Internally, the Austro-Hungarian conflict worsened. In the Hungarian parliament the Constitutional Party wanted expanded use of the Hungarian language in the joint army, while the Independence Party wanted an independent Hungarian army.30 Forty-nine South Slavs were accused of high treason for agitating for a Great Serb state.

The infantry units were still being raided to provide manpower for new units and to raise the strength of units in Bosnia. The average infantry company now had a daily present-for-duty strength of fifty to sixty men (less than half the peacetime strength of a German company), which made realistic training impossible. On the positive side, the Austrians finally began providing their artillery with modern equipment: guns with recoil brakes and armoured shields, aiming circles and telephones for fire control.

All aspects of Italian political, military and naval activity pointed to a sharpening of Italian animosity towards Austria.31 Characteristic was the continual improvement of Italian fortifications on the Austrian border, while nothing of the sort was being done on the French border.

The Serbian state was arming itself to the teeth.32 In the 1908/09 fiscal year the Serb state spent a sum equal to the receipts of the ordinary budget (80 million gold marks), then borrowed another 100 million gold marks, mostly from France (but some from Germany too), for armaments. The 1910 report said that they used the French money to acquire high-end equipment: modern artillery, artillery shells and machine guns.