8

Psychedelics: We Are One

If the words “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” don’t include the right to experiment with your own consciousness, then the Declaration of Independence isn’t worth the hemp it was written on.

Terence McKenna

In recent years, psychedelic drugs have become chic. Now, even square, middle-class conventionalists openly boast about their experiences under the influence of these substances, the authenticity of their psychedelic adventures magnified if they take place in an exotic location and are led by a shaman or some other tradition-claiming leader. Psychedelics comprise drugs that include lysergic acid diethylamide, better known as LSD; psilocybin, the active ingredient in magic mushrooms; dimethyltryptamine, also known as DMT, the psychoactive component of the ayahuasca brew; and other substances that are capable of producing profound alterations of perceptions and emotions.

Not long ago, I was exercising in the Columbia gym when a middle-aged white military veteran recognized me and wanted to share his exploits. He didn’t refer to these substances as psychedelics; he called them “plant medicines.” It was particularly important to him that I know he “didn’t get high” and only used the plants to facilitate his “spiritual journey.”

“What’s wrong with getting high?” I asked with a deadpan look on my face. Like a deer caught in the headlights, the vet froze before babbling a defensive and incoherent thought. Mind you, I knew it had taken him a fair amount of courage to share his story with me, so I didn’t want to come across as contemptuous. But that’s exactly what I felt: contempt. I wasn’t angry with him personally. It’s just that I had grown increasingly annoyed with the mental gymnastics that some psychedelic users perform in order to distance themselves from other drug users. The irritation I felt toward a few proponents of psychedelics was now starting to color my view of an entire class of drugs. I knew this wasn’t right.

Many people have shared with me their positive life-altering experiences after having used such drugs as ayahuasca, LSD, and psilocybin. Some have said they used them to feel at one with the universe or to sense their connectedness with fellow humans; others have said they used them to explore the meaning of their lives or to experience a kaleidoscope of magnificent colors and images.

Frankly, they seemed to be better people as a result. They are conscientious of others’ well-being and express a desire to bring about a more just world. For this, I am grateful. Yet I repeatedly encountered subtle cues of drug exceptionalism, a belief that psychedelics were somehow a superior class of drug. This disturbed me.

Fortunately, a chance meeting at a 2017 Christmas Eve party helped change my thinking about psychedelics. There I met filmmaker Amir Bar-Lev, who had recently completed his exquisite documentary, Long Strange Trip, about the rock band the Grateful Dead. At the time, I knew very little about the Dead and cared even less about their music. I knew the group had a rabid fan base, Dead Heads, who followed them around the country whenever they toured. But without much thought, I had pigeonholed Dead Heads as aging hippies who refused to grow up, and I had neglected to consider the possibility that their use of psychedelics might have been a way for them to explore freedom, a way for them to experience a more meaningful life.

Thus, as I learned more about the band and its journey, it wasn’t difficult for me to see why LSD and other psychedelics were key ingredients of the Dead experience. For instance, I doubt people would enjoy the Dead’s music as much as they do without the aid of psychedelics.

Amir is a thoughtful, sincere, and unassuming man. He doesn’t engage in conversations merely to toot his own horn. He listens attentively and patiently, and makes others want to do the same in his presence. As Amir spoke more about his film, my respect for the Dead, especially for Jerry Garcia, increased. Garcia was viewed by many as the band’s leader, but he steadfastly rejected this title up to his death in 1995. He was a firm believer in egalitarian principles and viewed each band member as an equal.

Amir caught me by surprise when he said that my position on adult drug use, specifically that it’s an unalienable right, was very much in line with Garcia’s view.

“Say what?” I asked incredulously as Amir made his case. I found it difficult to wrap my head around the notion that a psychedelic icon and I might share similar views on drugs. The current popular psychedelic movement seems to be dominated by people who justify their use of these drugs by couching it in medical or spiritual jargon. With some justification: over the past fifteen years or so, a growing number of studies have demonstrated that psychedelics, such as ketamine and psilocybin, produce a range of therapeutically beneficial outcomes, including reducing depressive mood states and provoking spiritually meaningful, personally transformative experiences.1 The media has warmly embraced these findings and generated a stream of positive buzz in the popular press.

Also, a growing number of popular books and public lectures tout the benefits of psychedelic use. Michael Pollan, in How to Change Your Mind, persuasively makes the case that psychedelics, such as LSD and psilocybin, can be personally transformative.2 A growing amount of scientific data backs him up. In her book A Really Good Day, Ayelet Waldman chronicles her monthlong experience of taking small subperceptual doses of LSD to treat her mood disorder.3 Waldman, like others, was inspired to use “microdoses” of LSD after having read James Fadiman’s The Psychedelic Explorer’s Guide.4 Despite the fact that there is virtually no solid evidence supporting microdoses of psychedelics to treat ailments or improve performance—the research hasn’t been done—microdosing has become the latest fad. Together, these developments have contributed to the removal of the stigma associated with using these substances, so long as the reason for use is not to get high. If your aim is to seek relief from an emotional or physical ailment or to achieve spiritual transcendence or to find your god, cool. But if you merely want to have a good time, not cool.

This arbitrary distinction makes no sense. Oftentimes the alleviation of pain, whether it’s psychologically or anatomically based, contributes to feelings of intense well-being and happiness, that is, to a sense of having “a good time.” Disentangling these deeply personal and idiosyncratic constructs is a difficult, if not an impossible, task. Similarly, the sacred experiences that positively affect one’s self-perception, worldview, goals, and ability to transcend one’s difficulties are hard to separate from one’s feelings of pleasure or happiness. What’s more, psychedelic drugs aren’t unique in their ability to produce these responses. I certainly have experienced all these effects after taking heroin or cocaine or MDMA or any number of the drugs that I discuss in this book.

Heroin and cocaine aren’t classified as psychedelics; however, MDMA, which is, in fact, structurally an amphetamine, is often classified as a psychedelic. Following a single administration of a large dose (> 250 mg), it’s absolutely possible to experience transient, prominent visual perceptual changes sometimes referred to as trails—a series of discrete images following moving objects. But most people who take MDMA aren’t seeking visual alterations and will never experience such effects because the typical doses used range from about 75 to 125 mg. Within this dose range, the magnanimous, euphoric, and empathy-enhancing effects that most of us seek from MDMA are far more likely to occur. Thus, if it were up to me—and it’s not—I wouldn’t label MDMA as a psychedelic. It’s an amphetamine, period.

Nonetheless, the discussion raises multiple broader issues about why specific drugs are categorized as psychedelics and others are not. Why have some psychedelics but not others managed to shed ridiculous stereotypes about their effects and users and thereby increase their popular acceptance and respectability? Methamphetamine, a chemical cousin of MDMA, is never referred to as a psychedelic. Why not? At large enough doses, it, too, can produce visual hallucinations. Plus, it has contributed to some of my most transcendent moments and has helped me solidify a few of my most important relationships. The majority of my methamphetamine experiences rival those I’ve had on MDMA and were a lot more meaningful than those I’ve had under the influence of so-called psychedelics.

Admittedly, thus far, I have taken only a few psychedelics: 4-acetoxy-DMT, 2-CB, ketamine, and psilocybin. In addition, because of my limited experiences with these substances, I have always taken doses on the low end of the spectrum. As I noted in Chapter 3, the amount of drug taken is one of the most crucial factors in determining the resulting effects. It’s possible that I might have found psychedelics more preferable had I pushed the dose. Relatedly, the setting under which drug use occurs can exert powerful influences on how the individual experiences the effects. Many people take psychedelics in the presence of a guide or a shaman, someone who ostensibly serves as a safety monitor as well as an experience interpreter. Some people find this comforting; I find it creepy and have never done so myself. For these reasons, perhaps it’s not fair to draw a comparison between my methamphetamine and my psychedelic experiences.

Regardless, the point I’m trying to make is that the way drugs are categorized is often discretionary and dependent upon whomever is doing the classifying. Most people, especially well-educated professionals, classify drugs in the manner that best serves their own purposes. For example, a drug such as MDMA is categorized as a psychedelic by respectable, middle-class white folks because they use and enjoy it. Methamphetamine, however, is not included among the psychedelics because middle-class drug elitists revile it. The perception, in the words of former Oklahoma governor Frank Keating, is that it’s “a white-trash drug.”5 Can you imagine if methamphetamine was labeled as a psychedelic? Respectable people would balk at this notion, fearing that the drug would ruin the rehabilitated reputation of their beloved psychedelics. By extension, no doubt, psychedelic users would worry that their own good names would be besmirched, too.

However, psychonauts—drug elitists who use psychedelics to explore altered states of consciousness—can’t readily discard phencyclidine, a.k.a. PCP or angel dust, because it has long been established as a psychedelic. You should also know, by the way, that the term psychonaut in itself is another attempt to dissociate middle-class psychedelic users from users of drugs such as crack and heroin, who are disapprovingly called “crackheads” or “dope fiends.”

In the 1950s, Parke, Davis & Company sought to develop PCP as an intravenous anesthetic. It was shown to be both safe and effective in patients. But the medication also produced in some people lingering depersonalization—a feeling of observing oneself from outside one’s body. This effect prompted concern and a more careful study of the full range of behavioral, neurological, and physiological effects produced by the drug. In one of the early studies, a large group of psychiatric residents and medical students were administered PCP intravenously at a dose level of 0.1 mg/kg, which is similar to doses used medically and recreationally.6 Consistent findings were distortions of body image and, again, depersonalization. Several research participants reported experiencing pleasurable effects, such as having dreamlike reveries; some displayed disorganized thinking. Not one became violent. Similar results have been replicated in multiple studies.

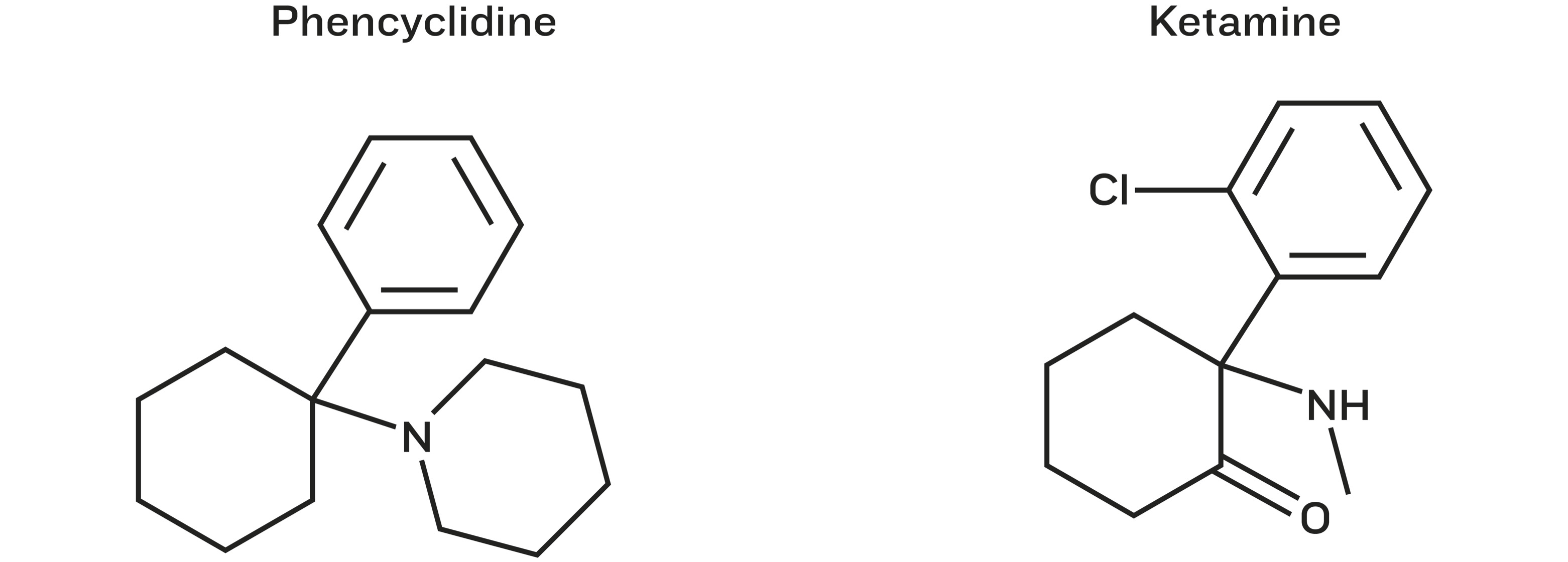

We now know that PCP produces many of its effects by selectively blocking a subtype of glutamate receptors called the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor. Glutamate, like dopamine and serotonin, is one of the brain’s many neurotransmitters. PCP is a selective NMDA receptor antagonist, or blocker. Ketamine—developed by altering PCP—is structurally similar to its parent compound (see Figure 5). The drug is also an NMDA receptor antagonist, but it’s not as selective as PCP. For instance, ketamine’s effects don’t last as long as those of PCP, which decreases the likelihood of unwanted side effects. Perhaps this is one of the reasons that ketamine has essentially supplanted PCP in medicine. Indeed, some of the most exciting recent findings from psychiatric research have been obtained using ketamine in the treatment of depression. Its therapeutic effects are observed within twenty-four hours, which is markedly faster than the seven to fourteen days it usually takes before the onset of beneficial results produced by traditional antidepressant medications like escitalopram, fluoxetine, or venlafaxine.

FIGURE 5

Chemical structure of phencyclidine (a.k.a. PCP: left) and ketamine (right)

Another factor that has practically eliminated the use of PCP in medicine has to do with claims that illicit use of the drug produces extraordinary violence in users. At some point in the 1970s, multiple media reports emerged making this allegation. Police narratives further cemented the supposed connection between PCP and violence. Perhaps you’ve heard the story that describes a PCP user who became uncontrollably violent, developed superhuman strength, and was impervious to pain after taking the drug? He had to be shot at least twenty-eight times in order for the police to restrain him— or so the story goes, anyway. Sound familiar? Remember the superhuman Negro cocaine fiend?

The fact is that there is no evidence the events in this story ever happened. It’s an urban legend. But that doesn’t seem to matter, because the story continues to live on and is retold repeatedly. This legend and others have contributed to the misconception that tremendous force is required when apprehending a suspected PCP user. In 1988, my late friend Dr. John Morgan and his colleagues were suspicious of unsubstantiated claims regarding PCP-induced violence, so they reviewed the clinical literature on the topic and published their findings in a peer-reviewed scientific journal.7 After carefully assessing nearly one hundred cases in which PCP was said to have caused people to engage in violent acts, the researchers found no connection between PCP and violence. They concluded that popular assumptions claiming PCP uniquely causes violence among its users are simply not warranted.

With solid scientific evidence, you might think the myth of the violent PCP user would eventually die. But that’s not how drug myths work. They don’t die, they get revitalized with each successive generation. The Rodney King incident is a case in point. In March 1991, four Los Angeles police officers—all white—were caught on camera savagely beating King—who was black—after they had stopped him for a traffic violation. The police beat King so badly that he sustained multiple serious injuries, including skull fractures, broken bones and teeth, and permanent brain damage. During the trial, police said that they used such great force because they thought King was “dusted”—under the influence of PCP. He wasn’t. His toxicology report revealed that he had only consumed alcohol.

Despite all this, the four officers were acquitted on April 29, 1992. Los Angeles erupted in protests and civil disobedience that lasted five days. A year later, two of the officers—Stacey Koon and Laurence Powell—were convicted in federal court of violating King’s civil rights and sentenced to two and a half years in prison. The events reignited the same national conversation about racism and police brutality that we have had for more than fifty years. Yet, as usual, the discourse was devoid of any interrogation of the mythical “PCP-induced violent criminal” as a credible police defense for the use of excessive force. In many black communities, this omission reverberates even today.

PCP Found in Body of Teen Shot 16 Times by Chicago Cop. That was the headline of an article published in the Chicago Tribune on April 15, 2015.8 My heart sank from merely reading the title, even though I had grown accustomed to police claiming that deadly force was necessary because the victim had PCP in his body. It only got worse as I read the entire article: “A knife-wielding teen had PCP in his system . . . it can cause its user to become aggressive and combative.” Here we go again.

I remembered having read in passing about the killing of seventeen-year-old Laquan McDonald—who was black—by a Chicago cop back in October 2014. The officer’s identity was withheld from the public for several months. But at the scene of the shooting, Pat Camden, police union spokesman, quickly took control of the narrative. He told the media that McDonald “walked up to a car and stabbed the tire of the car and kept walking.” When officers ordered McDonald to drop the knife, according to Camden, rather than complying, the teen supposedly lunged at police, prompting one officer to fire his gun. Reporting for the Chicago Tribune, Quinn Ford wrote, “McDonald was shot in the chest and . . . pronounced dead” shortly after.9 The implication was that the officer had fired only one shot while defending himself and other police. The story seemed familiar and a matter of fact. True to form, it was peddled to the public as the official version of the events that transpired on the night of October 20, 2014, when young McDonald was shot dead.

It turns out, the police lied, and the media did a piss-poor job of journalism. The public might not have known this and other crucial details if it were not for the exceptional investigative reporting of Jamie Kalven. Kalven obtained a copy of McDonald’s autopsy report through a Freedom of Information Act request. And on February 10, 2015, more than three months after the killing, he published an article in Slate.10 It detailed what Kalven had learned, including multiple pieces of information that impeached—or at least seriously called into question—the story told by the police and the mainstream media. Chief among them were that McDonald had been shot sixteen times, not once, as had been implied, and that the shooting was captured on a dashboard camera in one of the squad cars. Kalven called for the police to release the video.

City officials, including mayor Rahm Emanuel and police top brass, refused to make the video available to the public. They did, however, in collaboration with the media, employ the same tired script that had worked so well in previous incidents involving police misconduct: drag McDonald’s reputation through the mud and blame a drug for his alleged destructive behavior. Thus, findings from his toxicology report were released. PCP was found in his system, or so it was widely reported. Unsurprisingly, these accounts emphasized that the drug could make the users aggressive and violent. Not one of the reports mentioned that false positive toxicology screens for PCP are common for several prescription and over-the-counter drugs, including tramadol, venlafaxine, alprazolam, clonazepam, carvedilol, dextromethorphan, and diphenhydramine. Not one mentioned scientific evidence indicating that the link between PCP and violence is not justified.

But then, on November 24, 2015, thirteen months after the incident, a judge ordered city officials to release the dashcam video of the shooting. Its contents were horrifying and utterly contradicted the police account. McDonald was walking away from police when officer Jason Van Dyke—who is white—quickly moved toward the teen, opening fire while standing only about fifteen feet away. Van Dyke, in an act of what might be best described as depraved indifference for black life, pumped sixteen bullets into the adolescent’s body, several as McDonald lay defenseless on the pavement.

Van Dyke was put on paid desk duty from October 21, 2014, until the day the video was released to the public. Just hours before its release, Anita Alvarez, Cook County prosecutor, finally charged Van Dyke with first-degree murder. Clearly, her decision was influenced by mounting public pressure: she had viewed the video more than a year earlier without taking action against Van Dyke.11

Predictably, Van Dyke’s defense drew heavily on the “PCP-crazed black man” myth. One expert witness for the defense, James Thomas O’Donnell, claimed that PCP could cause “violent rage behavior” and could make a person feel as if he has “superhuman powers.” Van Dyke told the court that McDonald’s “face had no expression. His eyes were just bugging out of his head.” As a result, he shot McDonald because he feared for his life. The jury didn’t buy it. They convicted Van Dyke of second-degree murder and sixteen counts of aggravated battery with a firearm, one for each bullet he fired.

According to Illinois statutes, Van Dyke faced a prison sentence of four to twenty years for the murder conviction alone. In addition, each aggravated battery count carried a minimum of six years behind bars. In short, Van Dyke should have received a prison sentence of at least one hundred years. But judge Vincent Gaughan discounted each of the aggravated-battery convictions and sentenced him to only six years and nine months in prison. Van Dyke is eligible for parole after serving about three years behind bars. This doesn’t seem like justice. It’s demoralizing and disgraceful.

It’s hard for me to understand that a person, any person, could shoot another nonthreatening human sixteen times in cold blood. The fact that Chicago officials shielded Van Dyke from the consequences of his crime for more than a year still fills my heart with anguish. There is no way those in charge could have viewed McDonald as human, as deserving of humane treatment, as were they themselves and their loved ones. I think Jamie Kalven hit it on the head when he wrote, “Laquan McDonald—a citizen of Chicago so marginalized he was all but invisible until the moment of his death.”

There were so many other people who worked tirelessly to ensure that Laquan McDonald was finally seen. For one, William Calloway filed the Freedom of Information Act request that forced the city to produce the dashcam video for public viewing. He made it possible for all of us not only to see Laquan McDonald but also to see the chilling disregard for a black boy’s life displayed by some public authorities.

IN RECENT YEARS, psychedelic advocates have successfully pushed for wider mainstream acceptance of specific substances, while quietly dissociating themselves from others. For example, in 2019, Denver and Oakland passed measures that effectively decriminalized personal use of psilocybin mushrooms and other psychoactive plants and fungi. MDMA is expected to receive FDA approval for treating post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) within the next couple of years.

Meanwhile, psychedelic enthusiasts were conspicuously silent when Van Dyke used PCP as justification for his savagery. We also didn’t hear a peep from them when Betty Jo Shelby, a white Oklahoman police officer, evoked the “crazy nigger on PCP” defense to justify her killing of unarmed black Terence Crutcher. On September 16, 2016, the day Crutcher was killed, he had PCP in his system, but a video of the incident clearly indicates that he was neither aggressive nor violent. Nevertheless, Shelby was acquitted of manslaughter charges. The legend of the superhuman, violent PCP user will live on. This means more people will die needlessly.

I am deeply disturbed that there is a deafening silence from the psychedelic community while fellow drug users continue to be brutalized as a result of PCP-related misapprehensions. The question before me is, Why the silence in the face of such egregiously harmful mischaracterizations of PCP? It might have something to do with the fact that black men bear the brunt of this murder-justifying myth. Or it could be that psychonauts are simply strategically protecting their mission to ensure continued public support for a select few psychedelics, including DMT, MDMA, and psilocybin. Drawing attention to the fact that PCP is also a psychedelic might jeopardize the reputation, and thus the availability, of other psychedelics.

It’s also possible, however, that most people, including psychedelic advocates, don’t know PCP is a psychedelic. Plus, the “crazed black on PCP” legend is so ubiquitous in drug education and popular depictions that its validity isn’t questioned. Honestly, I don’t know the exact reason for the lack of public engagement by the community when it comes to correcting misinformation about PCP. I hope the information presented here helps to change this situation.

I vividly recall lamenting this in a recent conversation with my friend Rick Doblin. Rick is the founder and executive director of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS). Over the past thirty-plus years, he has worked tenaciously to get psychedelic research studies approved and funded. He has teamed up with researchers—some of whom even consider him their mortal enemy—as well as therapists, patients, and activists in this pursuit. Few people on the planet know the FDA’s drug-approval process better than Rick, who has a PhD in public policy and decades of experience working with and around regulatory agencies. MAPS, under Rick’s leadership, has been the single most important driving force behind the recent broader acceptance of psychedelic, especially of MDMA, use. But the thing that stands out most about Rick is his ever-present beaming smile. If ever there was an eternal optimist, it’s Rick.

In response to my frustration regarding the community’s quiescence surrounding misguided notions about PCP and violence, Rick expressed similar concerns. But he also asked me what I had done to change or improve the situation. I had avoided attending conferences and events focused exclusively on psychedelics, for many of the reasons mentioned above, including the oppressive lack of racial diversity and pervasive drug elitism in those spaces. Still, Rick’s question compelled me to acknowledge that I, too, was a member of the psychedelic community, and, as such, I had specific responsibilities, including providing education about issues that concerned me and should concern us all.

Rick challenged me to give a series of lectures at MAPS-sponsored events. Before I answered, he told me the story of how increasing the availability of psychedelics for adults became his life’s mission. In 1972, Rick, who is Jewish, was an anxiety-ridden college student. While he was deeply worried about the possibility of being sent to war in Vietnam, he was even more terrorized by the atrocities carried out during the Holocaust. “The fact that people could dehumanize others and kill them,” he told me. “That could be me one day.” Rick went on to say that psychedelics helped him to see how we’re all connected, to see the goodness in all humans. If others could also experience these types of insight, then perhaps, he believes, we would behave and live more compassionately. This belief is what motivates him every day to continue his mission.

I almost always come away from talks with Rick wanting to be a better person. Perhaps I had been unfair in castigating an entire community, I thought. I was reminded of the Maze song “We Are One.” I thought about the song’s lyrics that implores better treatment of each other and celebrates the joy that comes from it. I was determined to be better, to be more forgiving. True psychonauts, such as Rick, possess the values I want to emulate. So I agreed to do my part and to speak at his events whenever possible.

Rick’s openness and nonjudgmental approach strangely reminded me of how I once smugly dismissed Jerry Garcia as someone unworthy of serious consideration in discussions about drugs, liberty, or happiness. I was so wrong. Garcia, contrary to my uninformed view, used not only psychedelics but also other drugs such as cocaine and heroin. Unlike some in his circle, loved ones and bandmembers, he neither looked down on users of nonpsychedelic drugs nor disparaged others for engaging in behaviors outside societal conventions, so long as these behaviors did not infringe on other people’s freedoms. I wish more people in today’s psychedelic movement would emulate these specific aspects of the life that Garcia tried to live. If so, they might actually gain an appropriate appreciation for the country’s founding document—the Declaration of Independence—and for what Garcia meant when he said, “The pursuit of happiness. That’s the basic, ultimate freedom.”