Obstacles to Developing Sexual Intelligence

Winchester was a pretty nice guy—friendly bowler, cooperative husband, dependable dentist. No one in his life would describe him as stubborn—except me.

He originally came to me because he had lost much of his sexual desire and his erections were becoming less and less reliable. He loved his wife and really wanted their relationship, and sex life, to work. He described her as pretty, easygoing, and interested in sex.

“I just want sex to be the way it was,” he said plainly. “I love Janie, and I want us to have a normal sex life again.” Not unreasonable, I thought.

Winchester had been bowling almost every Monday for twenty years, with an impressive 220 average. But as with all sports, long-term, high-performance bowling had taken its toll on his body. He developed back pain in his late thirties, and it never went away. Year by year, it just got worse—a dull throb that became a sharp stab when he turned or bent the wrong way. As it happened, “the wrong way” included missionary position intercourse and getting on his knees to pleasure his wife orally.

That’s right: sex hurt. Almost every time—sometimes a little, sometimes a lot. The pain demanded that he limit the positions in which he had intercourse or oral sex. But remember, Winchester was stubborn; so he kept making love in his favorite positions, withstanding increasingly frequent stabs of pain. Eventually, he would lose his erection at those times. And eventually he began to avoid sex.

He didn’t want to admit this to Janie. We discussed his refusal to discuss this with her for many sessions, during which he acknowledged that she’d probably be sympathetic. “But I don’t want sympathy,” he complained. “I want to get on top of her and do her. Like a man.”

“Apparently,” I said quietly, “you can’t have that. You can have a lot of sexual treasures in your life, but apparently not that one.”

He was devastated. “I can never have good sex again?”

“Yes, you can,” I replied. “But not the way you think it’s supposed to be.” Most people think it’s only women who sometimes experience painful sex. That’s not accurate.

“Winchester,” I said, “this isn’t a sex problem so much as a spiritual or existential one. Only forty-four years old, you’re being confronted by your own mortality. You’re being forced to reinvent what it means to be a man.”

Winchester would be forced to “settle”—unless he could be creative and reinvent sex and himself. It’s something we’re all challenged to do sooner or later. Some people succeed, others fail; many refuse to try, withdrawing into bitterness, depression, or solipsism. I told Winchester I was certain he could do the work of reinventing sex and masculinity for himself. He was, he finally confessed, frightened. “Of succeeding or failing?” He wasn’t sure.

It took months. He worked through a bunch of stuff.

Toward the end of our work, he asked if he could bring in his wife. I was curious about her, of course. I’m always curious about the person who lives offstage in the drama of psychotherapy with a married person. But this was no time for indulging my curiosity—alas, there never is.

“Why do you want to bring her in?”

“So you can explain what we’ve discussed, and she can understand that I’m not just being a pussy.”

“You have to do that,” I said. “You don’t need me, and you shouldn’t have me do it.”

“Why?”

“Because part of growing up is sitting her down and telling her exactly who you are right now. It’s time to reach out to her and for you to lead the two of you through things collaboratively. You can do it.”

“It’s easier if you do it.”

“Yes, you’re right. But this isn’t about doing what’s easier. Sometimes sex is a vehicle for growing up, which is never the easiest option. It’s often the best, although not necessarily the easiest.”

So he told her. They made a decision—no more missionary position sex. They both cried—she was losing something too. “But I don’t want sex that hurts you,” she said. “And any sexual connection with you is way better than nothing. Way, way better.”

Sexual Intelligence is about focusing on the right things before, during, and after sex. But part of Sexual Intelligence is also about knowing what to let go of. Obviously, focusing on the wrong things makes it harder to focus on the right things.

So let’s actually name some common things on which people focus, and explain the importance of letting these things go. Then in the next chapters we can talk explicitly about what to focus on instead, and how.

Being “Normal”

This is an easy place to start, because we already took a long look at this issue all the way back in Chapter 2.

So this is just a reminder: my goal is not to reassure you that “even if you’re different, you’re normal.” No, my agenda is more ambitious: I want you to forget about the question of normality altogether.

I know that’s challenging, because it means claiming your own power to evaluate your sexuality, rather than getting the reassurance of comparing yourself to others. So how would letting go of this idea of sexual normality change things? Here’s one way: If you completely let go of it, wouldn’t you feel closer to your partner? Might there be something you’d be willing to ask or discuss with him or her about sex?

I’m betting there is. And that has to be good for your sex life.

So I propose that you Let It Go.

Intercourse

Penis-vagina intercourse is what most people call “real sex.”

If you’re old enough to remember life before the Internet, you’ll recall the bizarre Monica Lewinsky scandal, which seemed to last Sexual Intelligence a lifetime. It climaxed with President Bill Clinton swearing, before TV camera, wife, and God, that “I did not have sexual relations with that woman.”

It turned out he was being literal—“sexual relations” has long been a euphemism for penis-vagina intercourse, which he apparently did not have with “that woman.”

But of course he did other things that most people think of as sex. And so people accused Clinton of lying. He later apologized on national television for deliberately misleading people—underlining, however, that he had been legally accurate.

So whassup with intercourse? Why do I diss going all the way, hiding the salami, jumping someone’s bones, getting laid, fornicating, boinking, laying pipe, riding the love machine, shtupping, knocking boots, burying the bone, going to the drive-in, doing the horizontal mambo, effing, humping, nailing, hammering, pounding, drilling, porking, plowing, shagging, or screwing?

Okay, let us count the ways. The disadvantages of intercourse include:

• It’s the only kind of sex that requires an erection.

• It’s the only kind of sex that requires birth control.

• It’s not an especially effective way for most women to orgasm.

• It can be painful for women in middle age and beyond, and therefore painful for their partners, too.

• It’s an especially easy way to transmit diseases.

• It can be hard to fit the body parts together without looking at them (especially if you don’t talk much about doing so, either before or while you’re trying).

• It isn’t necessarily intimate (so quit using the word intimacy to mean sex or intercourse).

• It generally doesn’t get you excited if you aren’t already excited.

But the big problem isn’t actually with intercourse itself. It’s with our relationship to intercourse—the belief that it’s the only “real sex,” the feeling that everything else is “foreplay” (the second-rate stuff before intercourse), and the belief that once we get excited we need to “go all the way” in order to be successful and satisfied. This constricted view limits our flexibility, and is the exact opposite of what most people say they want from sex—playfulness, spontaneity, ease.

While much of this would be true no matter what else we might decide is “real sex,” making intercourse the Number One Special Sexual Activity creates the extra problem that “real sex” always carries the risk of unwanted conception.

If you don’t assume that all sex will end with intercourse, you can:

• Begin sexual activity without having to worry about your “function”

• Enjoy erotic activity without the distraction of monitoring “where it’s going”

• Focus on the activities you like rather than focusing on getting increasingly excited

So I propose that you Let It Go.

A Hierarchy of Sexual Activities

For most adults, cultural competency around sex includes a hierarchy: everyone knows that some sexual activities are somehow superior or more like “real sex” than others. Note that being “more like real sex” is not the same thing as being “more enjoyable.” People may disagree about which things are better than which, but most adults do believe in some sort of sexual hierarchy.

Different American cultures and ethnic groups value different aspects of sexuality, including, for example, modesty, experimentation, self-control, refusing contraception, multiple partners, being pain-free, female submission, the act of seduction, and orgasm itself. Nevertheless, the consensus in Western culture is that the pinnacle of the heterosexual hierarchy is intercourse. This means, depending on who you ask, that intercourse is the sexual activity that is the most “serious,” the most dangerous, the most enjoyable, the most intimate, the most godly, the most “natural,” or the most “normal.”

Most Americans would agree that right below intercourse is other genital sex with a partner (such as oral sex, anal sex, and hand jobs), followed by masturbation and non-genital sex. Kissing is a wild card, because for some people it’s boring, intrusive, or a turnoff; for others, kissing is the height of intimacy. (You can have intercourse when you’re angry, but kiss? Eeyew, gross!)

Commercial sex, Internet sex, phone sex, “alternative” or “kinky” sex (S/M, for example), fetishes (feet, urination, gloves, and so on)—each occupies a space of its own. For practitioners, these activities are very hot, while nonpractitioners usually just scratch their heads and say, “But where’s the sex in it?”

So how does attention to this imagined hierarchy undermine our satisfaction?

Believing in a sexual hierarchy devalues our experience—people dismiss what they’ve done (or been offered) as “only foreplay” or “not real sex.” The hierarchy can also make sex more complicated if partners disagree on the meaning of a certain activity. (For example, foot massage: sexy and intimate, or a not-sexy waste of time?)

A hierarchy introduces success and failure into sexual decision-making and experience; if you judge your sexual adventure as insufficiently high up on the ladder, you may feel cheated or self-critical. Similarly, a hierarchy introduces the idea of “dysfunction”: if there’s something you need to do to be sexually “successful,” that creates the category of “unable to do the thing to be successful”—i.e., dysfunction.

Deciding that it’s intercourse at the peak of the hierarchy, of course, brings its own special problems: the possibility of pregnancy, along with the requirement of an erect penis and a lubricated vagina. Overvaluing intercourse also encourages us to overfocus on orgasm, and it demeans self-touch with a partner instead of allowing us to see it as one of many equal erotic choices.

Sexual Intelligence involves knowing that our familiar sexual hierarchy is just a cultural artifact, and that we aren’t required to be loyal to it. For example, as Shere Hite documented forty years ago, men’s and women’s strongest orgasms are typically from masturbation, not partner sex; and for women, most orgasms occur from clitoral stimulation, not intercourse. Even though their own experience attests to this truth, many people ignore this and attempt to do sex the mythical “right way”—and get frustrated with the results.

Since the whole hierarchy is arbitrary, we shouldn’t be surprised when it changes over time. The cultural meaning of, say, cunnilingus has changed dramatically over the last one hundred years. The experience of losing one’s virginity is often quite different now than it was fifty years ago. And the meaning, incidence, and place in the hierarchy of anal sex have changed dramatically in just twenty-five years.

Of course, since the hierarchy is built on arbitrary social norms, any given activity may have more symbolic value than practical value for someone. That is, you may feel you should enjoy something more than you do, or you may choose to do something when you don’t especially enjoy it. (This may be especially true if, like many people today, you’re watching more porn.) Examples might include anal play, “tit fucking,” and intercourse itself—activities valued by some people more for what they represent than for the amount of pleasure they actually offer.

When two people have sex, it’s hard enough for them to find common interests, get their bodies to do what they want them to do, and find the time, energy, and privacy to do it. Caring too much about which activities are “right” or somehow acceptable makes sex—and life—way too complicated. We’re much better off discovering what we like, learning how to create it, and getting comfortable with instructing others on our preferences. Which kind of sex is better than which other kind of sex? Those old hierarchies are for accountants, not lovers.

So what about oral sex? A hand job? Phone sex? Masturbating during an Internet chat session? Going to a strip club? Reading a romance novel and getting excited? Over the years I’ve had many patients argue over whether they’d just been caught having “an affair,” or doing something they claimed was far less important. “That’s not sex, that’s typing,” said one woman defending her chat-room escapades. It reminded me of what Truman Capote said decades ago about Jack Kerouac’s book On the Road: “That’s not writing, that’s typing.”

So I propose that you Let It Go.

Performance Obsession—The Agony of Failure, the Anxiety of Success

For some people, not failing is the best that sex ever gets. This is especially true of many young people, before they’ve established their internal sense of sexual identity and adequacy.

We can all do better than that.

Many men and women come into my office wanting help with this, saying things like: “My performance isn’t so good,” or, “I’m about to start sleeping with this new guy, and given my ugly last relationship, I want to make sure my performance doesn’t disappoint him.”

Why turn sex into a performance? It doesn’t start out that way—we make it that way through our vision. It’s similar to the way some people turn drinking into a performance—they brag about drinking more than everyone else, or tease others about not being able to hold their liquor. I recall a patient who bragged, “I could drink a table under the table,” which I guess is a lot. Meanwhile, other people think drinking is just drinking.

Imagine if we did this with, say, eating broccoli: “Wow, that guy can put away more broccoli than anyone. And not even fart afterwards. What a man!” Or: “Hey, Mary could hardly down a single stalk of broccoli last week. I bet she won’t be showing her face around here for a while!”

Constantly monitoring your performance not only erodes your enjoyment of sex, it also makes it harder to “perform” the way you want to. That’s because, in real life, “performance” isn’t voluntary; it’s part of the autonomic nervous system, the body’s uncontrollable response to stimuli, both internal and external. If you’re paying attention to your desire to perform (or your terror about failing to do so), it’s that much harder to feel, smell, touch, and taste the body you’re with, or to see that person smile.

Not surprisingly, our culture’s emphasis on performance has made erection drugs enormously successful. Also not surprisingly, more and more young men without erection problems are using these drugs. Over the years, I’ve had a few dozen patients under twenty-five tell me, “It’s just for insurance. If there’s a good chance I’ll be hooking up, I take it. Nobody has to know, and there’s no harm done.”

Well, it’s not as bad for you as shooting heroin, but I actually do think there’s harm done. Specifically, young guys who take Viagra-type drugs when they don’t need them never get to find out they don’t need them. They don’t get to build their confidence, because when they get the adequate erections they desire, they credit the drug. Some guys say that this effect is in fact what’s building their confidence and that eventually they’ll stop taking the drug, but I haven’t seen that a whole lot since the drug became popular over a decade ago.

There’s also the secrecy that develops—these guys rarely tell their partners they’re using an erection drug, and the more they use it the bigger the secret becomes. And while that isn’t as bad as shooting heroin either, I’ve never seen a relationship that needed more secrets.

Some psychologists say that people attend to their performance as a way of maintaining psychological distance with a partner. Or that they’re so narcissistic that their real erotic object is their own body and its performance, rather than their partner. Perhaps that’s true. Whether people do this to create the distance or simply accept the distance that results (or don’t even notice it) is an open question—but emotional distance is rarely a good thing.

It’s ironic: people focused on performance typically say, “I want to give my partner a good time,” or, “I don’t want to disappoint my partner.” Then they emotionally withdraw from their partner to pursue their own agenda of creating a sexual performance they feel proud of, rather than being emotionally present, which most people prefer in a partner.

So I propose that you Let It Go.

“Function” and “Dysfunction”

Too many people think that if your penis or vulva does tricks when and how you want, you “function” right, and that if not, you have a “dysfunction.”

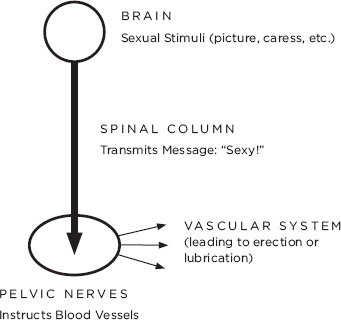

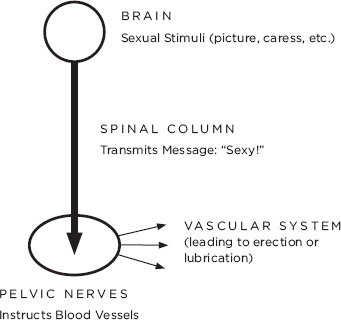

Most people stuck on this model don’t seem to appreciate the role of emotion in facilitating or blocking sexual “function.” We get erect or wet (genitally, I mean) as the result of an impressive chain of events:

• Our brain perceives a sexual message (for some, a photo of Bristol Palin; for others, that’s the end of erections for a month).

• Our brain sends a message down the spinal column toward the pelvic nerves.

• The pelvic nerves send a message to the small blood vessels radiating out from the pelvis.

• The blood vessels receive the message and get to work: they dilate, allowing more blood to flow in.

• The increased blood flow fills the penis or clitoris, making it hard, and triggers the wetness that eventually sweats through the vaginal wall into the vagina.

How the Mind/Body Creates Sexual Arousal

It’s a very cool process when it works. But obviously, a lot can go wrong: a problem with the information transfer between brain and spinal column, between spinal column and pelvic nerves, or between pelvic nerves and blood vessels; the nonresponsiveness of the blood vessels once they do get the message; or the disruptions created by diseases like diabetes, high blood pressure, arteriosclerosis, and Alzheimer’s, as well as by spinal cord injuries (from sports, car accidents, military injuries, and so on).

There’s another possible problem: the spinal column also carries our emotions, which are basically simple electrical impulses (I know, a hopelessly romantic point of view). Note that the message “Alert—sexual excitement, prepare for pelvic hydraulics!” is carried down the same pipe as the message “I don’t trust you, mister,” or, “You still haven’t apologized to my mother,” or, “What the hell am I doing here?” These emotions serve as noise, which can prevent a clean sexual signal from getting all the way to the pelvis from the brain. The result? Not enough signal to create vasocongestion down there, or to keep it flowing after it starts. You know that old Bulgarian saying: inadequate vasocongestion, inadequate “function.”

“Sexual dysfunction” is when the brain–spinal column– pelvic nerves–vascular system information transfer doesn’t work smoothly.

A high percentage of people who come to see me with “sexual dysfunction” are experiencing emotional noise while they’re expecting a sexual message to get them or keep them aroused. That’s not sexual dysfunction; that’s the body working fine, just contrary to its owner’s wishes.

Think of it this way: if you eat at McDonald’s three times a day for a month, sooner or later you’re going to get a serious stomach-ache. When you go to the doctor with awful cramps, the first question will be: “What have you been eating?” When you tell the truth (proudly or shamefaced), the doctor will say, “Oh, good news—your stomach works fine. Your stomach isn’t designed to digest McDonald’s food smoothly three times a day for a month. So your pain is a sign that your stomach is working perfectly. Now go away and start eating broccoli.”

It’s the same thing with your penis or vulva. When you’re metaphorically eating at McDonald’s three times a day—when you’re filled with a lot of anger, sadness, loneliness, confusion, or shame—your body isn’t supposed to be able to get and stay hot. This is true whether you’re aware of those feelings or not, or whether you admit them to yourself or not. If you’re making love with a new friend and she suddenly says, “Omigod, I think I hear my husband coming up the stairs,” you’re definitely going to lose your erection. That isn’t erectile dysfunction—you’re not supposed to be able to keep an erection in such a situation. At that point, your body needs the blood for more important things—like propelling itself out the window.

So I propose that you Let It Go.

The Need for a Perfect Environment for Sex

Consider Paris, a very special place. Anyone can enjoy it if they have plenty of money, the weather is great, and they speak French. Since any given trip to Paris may lack one, two, or all three of these, however, the trick is to be able to enjoy Paris without them.

Many people are capable of wanting and enjoying sex under the perfect conditions: the right partner; two perfectly clean bodies; complete privacy (I knew a patient so shy, she would only make love during a total eclipse of the sun, when there wouldn’t be light anywhere within a thousand miles); not a single chore to do (I had a patient once who made her kids promise to wash the dishes and do the laundry immediately if they ever found her dead); no quarrels with their mate in at least six years; and both partners having gone to the gym and flossed that very day.

In other words, practically never. Maybe even never again.

Adults live complicated lives, and there are no time-outs. Therefore, if we want to enjoy sex, we will almost always do so under less-than-ideal conditions. That doesn’t mean we don’t have preferences and even have-tos; of course we do.

For some people, their have-to is brushing teeth; for others it’s not having sex during their period, and for still others sex can’t happen when they have a sinus headache or their back is out. I’ve known patients who couldn’t have sex on an empty stomach, or while country music was playing, or with a pet in the room. I’ve also had patients who insisted on having their pet in the room during sex. Even exhibitionists are a heterogeneous group.

But think of this as an opt-in versus opt-out situation. Assuming our basic conditions are met, we need to be leaning toward yes unless there’s a problem—rather than leaning toward no unless a long list of conditions is filled and a long list of deal-breakers is absent. If you’re oriented toward reasons that you can’t have sex on a given occasion rather than reasons that you can, you will benefit from enhancing your Sexual Intelligence.

A special note for parents: if you can’t learn how to enjoy sex with kids in the house (presumably asleep, although less so as they get older), you’re doomed to eighteen or more years of no sex (unless, of course, you can afford boarding school for either them or you).

Some people are fine with this. But if you’ll be continually grumbling to your mate or resentful of your kids, you should develop a repertoire of activities and vocal levels: sex-with-kids-in-house (sleeping), sex-with-kids-in-house (awake), and sex-with-kids-not-in-house. For some people, there’s also sex-with-spouse-not-in-house, but that’s a different story entirely.

So I propose that you Let It Go.

The Need for “Spontaneity” and Noncommunication

What adult does anything spontaneously anymore?

Let me put that another way: most of the spontaneity in adult life comes from good planning, deliberate maintenance of inventory, and a dependable system for doing things. Here are a few examples:

• Going bike-riding: Whether you plan ahead or do it spur-of-the-moment, you have to own a bike; know how to ride; have the right clothes for the weather (maybe you even check weather.com before you dress); put air in the tires; fill your water bottle (you do have one, right?); and bring your chain and lock (and don’t forget the key). Whew, I’m half-exhausted just thinking about it. Well, if you do all this, then you can bike anywhere you like, for as long as you like. If your clothes match the weather, that is.

• Going on a picnic: The week before, we divide up who’s going to bring food, drinks, a blanket, a Frisbee, and music. Then we can pursue these things in any order we like or even skip a few. But we can’t do much that requires equipment we didn’t bring.

• Making chili for four: After your bike ride or picnic, you feel generous and decide to invite people over for dinner. C’mon over this second, you say. Fortunately, you have a few essential ingredients for this gathering: you’ve stored some meat in the freezer; you have a microwave oven to defrost things; you cleaned up the kitchen last night; and you know how to cook. After you’ve shared half a bottle of chardonnay, you can decide when you’re going to eat and whether vegetables will just ruin the mood.

• Finally, making love: When you get into the bedroom—with a stop off at the bathroom first—you set up your temporary love-shack. You take out whatever supplies are appropriate: birth control, lubricant, disease protection, toys, leather and lace. Having talked about it, you know that showers won’t be necessary. And you’ve discussed spanking (not for you), sharing fantasies about co-workers (not for your partner), and talking nasty (you both like it). Having done this planning (including that stop in the bathroom), having had a key conversation or two, now you can have “spontaneous” sex—you can do whatever activities you both desire, in any order you like. You can even skip “normal” sex if you want to.

You’ve heard that in some cases “less is more”? Well, when it comes to sex, “spontaneity” requires planning.

Whether you’re thirty, fifty, or seventy, most people remember the “spontaneity” of sex in their early years. But let’s take a closer look at these “memories.”

First, it wasn’t completely spontaneous—typically, one or both parties had been thinking about it night and day; one or both parties had been rehearsing how to make it happen, how to make it seem spontaneous, and how to dress just right for it (for example, looking available enough to keep a partner interested, but not so available as to be considered a slut). And in terms of repertoire, our first sex is rarely spontaneous, as many of us are trying to fit into preexisting categories: a real man, a woman in love, a tormented romantic soul, and so on.

That said, there often was a spontaneous side to our early sexual experiences: many of us were drunk or stoned, we often didn’t think much about the implications (Do I call the next day? What does she think this means? Will we still be friends?), and perhaps we did very little about contraception or disease protection. In fact, if you could do it all over again, would you do your early sexual experiences exactly the same? Or would you prepare a bit more, communicate a bit better, give some more thought to birth control? How about a bit more light in the room? So much for the ideal of “spontaneity.”

And of course, that early “spontaneous” sex often led to a certain amount of heartbreak. Heartbreak is an occupational hazard of new sexual experiences and relationships, of course, but some of them could have been avoided by a few honest, nonspontaneous words: “I’ve never done this before,” “I haven’t done this in a long time,” “If we do this I want it to mean we’re a couple,” “I have herpes,” “I usually don’t orgasm with a new person, so don’t take it personally,” “I feel really self-conscious about my scar,” “Let’s agree that this is private and we won’t tell anyone, okay?”

Some would argue that these mini-conversations (which rarely feel “mini,” which is why we hesitate to have them) take the “romance” out of sex. I think that’s just fine—who needs some spurious “romance” when you can have real sex in real life? There’s so much mystery integral to our sexuality, so much romance in getting to know a new body and a new person (or enjoying familiar things we’ve learned to expect), that we really don’t need to add more of either one by hesitating to communicate, plan, or acknowledge what we’re doing.

I believe that when people say they want sex to be spontaneous, they’re thinking one or more of the following:

• I don’t want to think about what I’m doing.

• I don’t want to think about the consequences of what I’m doing.

• I don’t want to be that close to the person I’m doing this with.

• I’m concerned that if either of us thinks about this, we won’t do it.

• I’m concerned that talking about what we’re doing will make it less interesting.

• I’m concerned that if I think too much about it my body won’t “function.”

I’m sympathetic about concerns like these, although my response to all of them is the same: don’t pursue a sexual situation that you’re not comfortable with. Too many people, especially young people, treat sexual opportunity as if it were Halley’s Comet—like it comes around so rarely that they should grab it when they can, even if that means doing it under less than ideal conditions—that is, “spontaneously.”

No. Unless you’re in the French Foreign Legion, sex comes around again.

The fact is, “spontaneous” (read: nonthinking, noncommunicative) sex has too many disadvantages:

• You may feel isolated or alone while it’s happening.

• You may feel that your performance is the main thing you offer.

• Your partner may feel that their performance is the main thing they offer.

• It often means no lubricant, contraception, or disease consideration, and limited physical comfort.

• But most of all, you miss some of the best parts of sex: being present, having a partner who’s present, directing what’s happening, being conscious.

So I propose that you Let It Go.

The Idea That Sex Has Inherent Meaning

Sex has no inherent meaning. We can make individual sexual experiences meaningful, and if we have enough of them, we can say that sex is meaningful to us. But sex is meaningless until and unless we give it meaning. This gives us a lot of responsibility and a lot of power.

That said, most people give sex too much meaning, and the wrong kind of meaning. Then they complain that sex is too complicated. And they’re right—when we make sex complicated, it’s, um, complicated. It makes each sexual encounter too, um, meaningful. There’s too much riding on each occasion, which creates pressure and anxiety that undermine sex.

What are the typical meanings that various people and institutions claim sex has? I periodically hear people say that the meaning of, foundation of, or distinctive feature of human sexuality is:

• Intimacy

• A divine gift to humans, which should be expressed divinely

• A validation of our identities as men or women

• A way to strengthen the (holy, matrimonial) relationship

• The ultimate expression of love

• The ultimate gift to someone

• The source of life (via conception)

• What people do if they love each other

• The fulfillment of desire

To make things even more complicated, it’s also common for people to believe that:

• Healthy sexual desire is driven primarily by love

• Healthy, mature people are driven to sexual exclusivity

It’s bad enough that people give sex all these meanings—which are too complicated, and often contrary to experience. (Everyone’s had sex that was not at all “intimate,” and most couples have had sex that didn’t nurture the relationship one bit.) Believing that these features are or should be inherent in sex just makes things worse—because when we experience sex that doesn’t reflect these ideals, we assume there’s something wrong with us or our partner.

So what’s the difference between believing that sex has meaning and giving it meaning? Why does it matter?

If you believe that sex has inherent meaning, you inevitably want to have sex in ways that are likely to deliver that meaning. It’s one more way of being loyal to sexual standards outside of yourself, and it’s as far from “spontaneous” and “being yourself” as possible. Many people become concerned that they’re not fulfilling some duty to “honor” sex (a common idea among those who believe that God has gifted us with our sexuality). It’s part of America’s obsession with not making love “like animals”—as if we do it in ways that are somehow superior to other creatures.

I don’t think we should be serving sex; I think sex should serve each of us. Each sexual encounter is an opportunity for us to create sex anew for ourselves, to use it to refresh and explore ourselves in personally relevant ways. If we think that sex has inherent meaning, and that it’s our job to both find and conform to that meaning, we won’t be able to see sex freshly, we won’t be motivated to perceive or act counterintuitively, and we’ll accept arbitrary, outside limits on our erotic activities. If you tolerate sex becoming smaller, you will become smaller along with it.

If you want to give sex meaning, go ahead. At the same time, remember that you can enjoy the freedom of playful, amoral (not immoral, amoral) sex. As Woody Allen says, “Sex without love is meaningless, but as far as meaningless experiences go, it’s pretty damn good.”

Some social institutions purport to tell us what sex means or what it “should” embody. Most organized religion, for example, is highly involved in controlling and limiting people’s sexual expression. In fact, American Christianity has institutionalized its sexual norms politically, in abstinence (“sex education”) training, obscenity laws, and pharmacists’ “conscience clauses.” Be wary of those who claim to know what sex “means” or what its “purpose” is—they want to control you by explaining how you should adapt your sexual expression so it’s right.

With the Sexual Intelligence perspective that sex has only emergent meaning, you can experience a huge range of sexual feelings and meanings. Without this perspective, however, much of this range is either invisible, or, worse, repugnant, and by definition excluded. It brings to mind Nietzsche’s aphorism, “Those who danced were thought insane by those who couldn’t hear the music.” You and your partner have the human privilege of listening to your own sexual music and dancing to it in your own unique way.

Finally, some people are afraid that if sex has inherent meaning and they don’t salute it, they won’t behave ethically. This is a common idea of those involved with religion—that it’s religion that makes people behave ethically, and that lack of religion would remove this ethical regulator. This is a terribly pessimistic view of people—that they behave well only because they’ve been promised a reward after they die, or they fear great punishment after they die.

That’s how five-year-olds think—reward and punishment. As adults, we can do better than that.

So I propose that you Let It Go.