And so we went to the museum on the corner of Main Street and Chapel Lane. It had once been a posh town house, but in the mid-eighteen hundreds the family went back to England. Dad said it was the rain, boredom and the constant diet of bacon and watery cabbage that drove them away.

‘Besides,’ he went on, ‘the shortage of other gentry around here meant they had only one another to talk to. There are only so many ways you can talk to the same people about the Irish weather and hunting foxes before going doolally.’

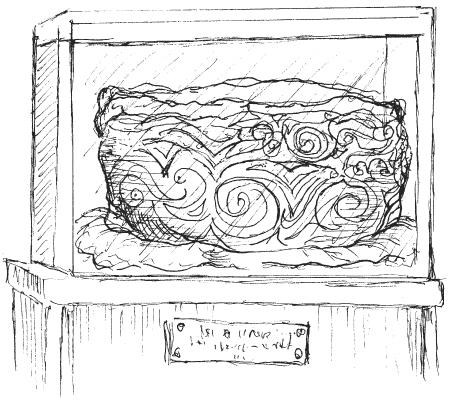

We wandered through the old farm things and moth-eaten animals with bits of their stuffing leaking out. It didn’t take long to find the glass case with the stone in it. Shane saw it first.

‘Wow!’ he shouted. ‘Look, Milo!’

Sure enough, there it was, sitting on a green velvet cloth. Shane took his stone from the bag and we compared it to the one in the case.

‘It’s a dead ringer for yours,’ I said.

‘It’s part of it!’ exclaimed Shane. ‘Can’t you see? If the two pieces were put together, the pattern would form complete circles. This is mega.’

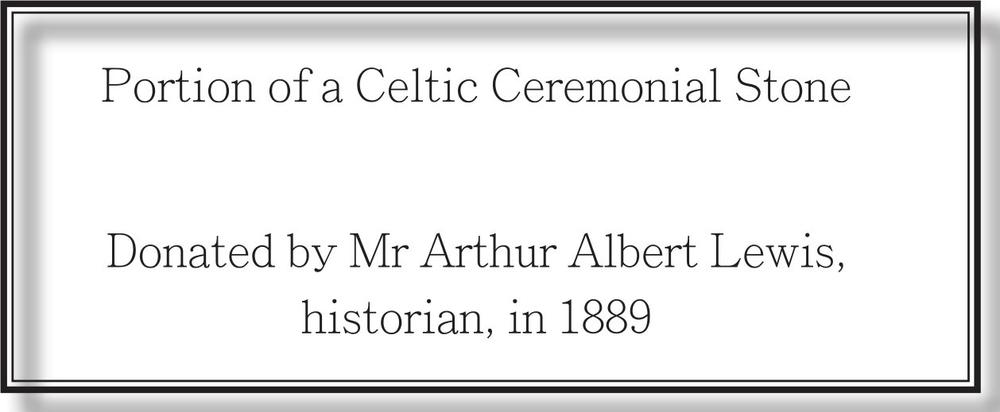

On a plaque beside the display window there was a sign, which said:

Underneath there was more writing, but the words were covered by years of dust.

‘That’s him!’ exclaimed Shane, practically dancing with wobbly excitement. ‘See? I told you. That’s the man who used to live in our house. If this bit of stone was in our garden, then that bit must have been there too.’

‘Keep your voice down,’ I said. ‘We’ll be thrown out.’

Too late.

A man with a frown attached to his hairy eyebrows was already making his way towards us. It was Mister Conway, keeper of the museum, wearing a dusty suit that fitted right in with the surroundings.

Shane shoved the stone into the takeaway bag before he could see it.

‘What are you two up to?’ Mister Conway asked.

‘What makes you think we’re up to anything?’ said Shane. ‘We only came to look at the old stuff.’

‘None of your lip,’ snapped Mister Conway. ‘I’ve had my eye on you two.’

‘Like, you think we came in to steal a rusty plough or a wormy butter churn?’ said Shane.

‘Ssshh, Shane,’ I muttered, elbowing his tummy. ‘Come on. We were just leaving anyway.’ I pulled him after me down the front steps into the sunny street.

Shane couldn’t stop talking about the two bits of stone. You’d think they were gold nuggets the way he was going on.

‘They’re just stones, Shane,’ I said. ‘So they were once stuck together, but they’re still only bits of old stone with squiggly bits on them.’

There it was, that strange, tingly feeling again.