10.

James Clark Ross Locates Magnetic North

The nineteenth-century search for the Northwest Passage was linked to the drive to solve the mystery of the shifting north magnetic pole. The two quests, geographical and scientific, had been intertwined since the 1300s, when science-minded “philosophers” began wrestling with geomagnetism. They were responding to European mariners who claimed that, when they sailed far to the north, their compasses ceased to be reliable.

By the 1500s, with the growth of international trade dependent on ships, this problem grew more urgent. Leading thinkers suggested that compass needles might be attracted by Polaris, the pole star, or perhaps by a magnetic mountain or island situated near the North Pole. But given the fixed position of such natural attractors, why would compasses behave so erratically? Perhaps the instruments themselves were faulty?

In 1538, to test this theory, the chief pilot of the Portuguese navy sailed out of Lisbon on a three-year voyage to the East Indies. João de Castro carried the most advanced magnetic compass yet made, a splendid “shadow instrument” that measured magnetic direction and solar altitude. De Castro made forty-three careful observations, and his wildly fluctuating readings made no sense whatsoever.

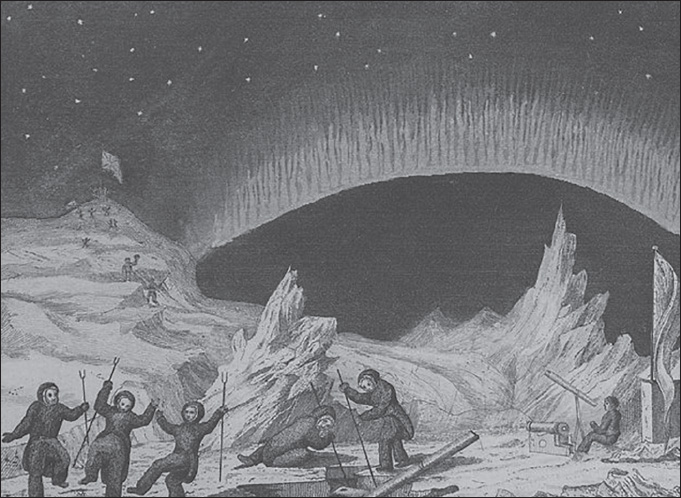

Bizarre theories about the shifting north magnetic pole persisted through the nineteenth century. They were reflected in this fanciful depiction of the 1831 celebration that ensued when James Clark Ross became the first to locate the pole.

A few years after de Castro returned with his bewildering results, the royal cosmographer of Seville, Pedro de Medina, published a widely translated manual insisting that compass variation was the result of inconsistent materials and human error. From his armchair in southern Spain, he declared, reassuringly, that well-made compasses would always point to the geographical North Pole. The manufacturers were at fault.

Those who built the instruments thought otherwise. Robert Norman, a leading British compass maker, began experimenting. He mounted compass needles on a vertical pivot and so discovered “magnetic dip” or inclination: the needles always dipped below the horizon line. The north-south or bipolar nature of any magnet had been established three centuries before. Now, Norman concluded that the north end of a magnet was pulled downwards by a “point respective” inside the Earth. In 1581, he published this argument in an influential pamphlet called The Newe Attractive. Moving beyond theorizing, it sought to provide mariners with practical solutions to navigational challenges. In this, however, it proved useless.

Mariners continued blaming their compasses until the early 1600s, when Englishman William Gilbert, physician to Queen Elizabeth I, revolutionized thinking on the subject. Born in Colchester, England, in 1544, Gilbert was the son of a prosperous “borough recorder” or magistrate. He attended St. John’s College, Cambridge, and graduated as a doctor at age twenty-five. Then he travelled on the continent and practised medicine in London, becoming a fellow of the College of Physicians in 1573, and president of that institution in 1600.

While ascending to professional eminence, Gilbert devoted his attention to exploring the mysteries of Earth’s magnetism. Writing in Latin, he defined the north magnetic pole as the point where a compass needle points vertically downwards—a definition that still stands. And in 1600, he published De Magnete, usually referred to in English as On the Magnet. This pioneering work relied on physical experiments to make its case. It surfaced at the tail end of the Renaissance, when universities were still teaching that the heavens revolved around the Earth and the natural magnet, or “loadstone,” could attract or move iron because it had a soul.

De Magnete was revolutionary in both argument and method. By relying mainly on experimentation—on trial, error and discussion—Gilbert pioneered what would become known as the scientific method. He built a “terrella,” a model Earth with a magnet inside. He used this to test compass needles and demonstrate, by analogy, the workings of planetary magnetism. By carving out miniature “oceans” and adding tiny “mountains,” he showed how raised or lowered land masses can cause compass variations. He also designed a “dip circle” to measure magnetic inclination. He hoped that navigators might be able to use this instrument to determine latitude, a practice that would show “how far from unproductive magnetic philosophy is.”

Gilbert argued, and demonstrated with his terrella, that compass needles point north because the Earth is itself a spherical loadstone—a giant magnet. By moving beyond opinion and argument into experimentation, he pointed the way forward for science. Two centuries would elapse before anyone would again make such a profound contribution to “terrestrial magnetism,” integrating all that had been learned during the intervening decades and laying the foundations of another advance. That figure, the man who inspired the international enterprise called the Magnetic Crusade, would strongly influence such Arctic explorers as James Clark Ross, John Franklin, Elisha Kent Kane and Roald Amundsen. His name was Alexander von Humboldt.

Like Einstein in a later century, Humboldt was a scientific colossus who dominated an era. In addition to other accomplishments, his probing of “terrestrial magnetism” laid the foundations of twenty-first-century geomagnetism and geophysics. He pointed the way to contemporary understanding of Earth’s shifting magnetic poles. And he did so by insisting on the importance of measurement and observation.

Humboldt led by example. In 1800, while travelling rough in South America, he took 124 sets of magnetic observations through 115° of longitude and 64° of latitude. He located the magnetic equator and determined that Earth’s magnetic intensity varies with distance from that equator—a discovery that would enable mathematicians to develop a formula describing the planet’s magnetic field.

Back in Berlin, he set up a magnetic laboratory in a small wooden outbuilding. Over a period of thirteen months, he took more than six thousand daily observations. Once, with a single assistant, he went seven straight days and nights, reading magnetic variations every half hour—a marathon that, he admitted, left him “somewhat exhausted.”

Humboldt convinced Carl Friedrich Gauss, the “mathematical genius of the age,” to tackle a challenge that had stumped everyone else: how to make sense of magnetic observations. Gauss showed him how to make crucial calculations. Yet even that peerless mathematician confirmed what Humboldt already suspected. Magnetic science needed more experimental data. To solve the mystery of Earth’s magnetism, and of the shifting magnetic poles, scientists required a global network of magnetic observatories.

Generations of polar explorers would participate in gathering these—that enterprise called the Magnetic Crusade. In Britain, the deputy leader was Edward Sabine, an Irish geophysicist we have already encountered. In 1818 and 1819, Sabine took magnetic observations while sailing as a Royal Artillery captain, first with John Ross and then with Edward Parry. He attributed changes in magnetic intensity to either a fluctuation in the Earth’s magnetic intensity or the shifting of the north magnetic pole. Sabine called for more observations to be taken at both the north and south magnetic poles.

Bent on producing as complete a magnetic survey of the globe as possible, Sabine orchestrated the building of magnetic observatories throughout the British Empire, from Hobart to Cape Town and Toronto. As well, he recruited Royal Navy officers to the quest. During the 1818 Ross expedition, William Edward Parry had written excitedly that “an amazing increase” in compass variation had taken place since the 1600s, when William Baffin took readings at the entrance to Lancaster Sound. And when Parry led his own breakthrough voyage in 1819, he and Sabine paid “unremitting attention” to magnetic readings, which were “likely to prove of almost equal importance” with locating a northwest passage. Parry was committed. Yet of all those Royal Navy officers influenced by Sabine, James Clark Ross stands tallest.

Born in 1800, the son of a London businessman, J. C. Ross joined the Royal Navy as he turned twelve. He served with his uncle, John Ross, for six years, rising steadily through the ranks. In 1818, as we have seen, he sailed to the Arctic with his uncle. The next year, with Edward Parry, he reached Winter Harbour. Young Ross sailed again with Parry in 1821, taking part in land surveys and serving as a naturalist. In 1825, his third expedition with Parry nearly ended in disaster. After spending one winter in Prince Regent Inlet, one of the expedition’s two ships, the Fury, was driven onto rocks and smashed beneath a cliff on Somerset Island. The sailors managed to get home in the other vessel.

In June 1829, with five Arctic voyages behind him, James Clark Ross sailed as second-in-command to his uncle, who had secured private financing for yet another Northwest Passage expedition. The men departed from Loch Ryan, on the west coast of Scotland, with two ships, the side-wheeler Victory towing the smaller Krusenstern. None of the sailors had any idea that they were about to be tested on an epic scale.

In southern Greenland, with the Victory’s engines giving no end of trouble, the Rosses plundered an abandoned whaler and rigged the vessel as a schooner. The ships entered Lancaster Sound on August 7 and swung south into Prince Regent Inlet five days later. The officers investigated “Fury Beach,” site of the 1825 wreck, and found the stores surprisingly intact, with tins of preserved meat and vegetables and much else. The expedition proceeded into the southern reaches of the Inlet and in October, settled in for the winter at “Felix Harbour,” which John Ross named after his sponsor, gin merchant Felix Booth. So far, so good.

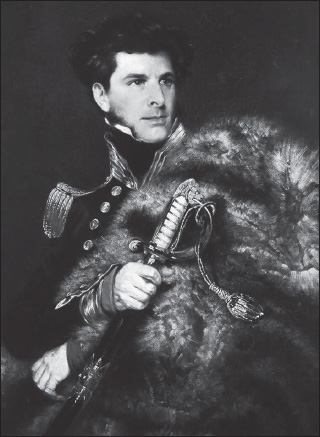

James Clark Ross in 1834, soon after he arrived back in England after pinpointing the north magnetic pole. The artist: John R. Wildman.

The men built a wall of snow blocks around the ship, which was roofed as per standard naval practice. They rigged up piping over the steam kitchen and baking oven to carry rising vapour into tanks. This kept the inside of the ship dry and comfortable at lower temperatures. The men also built an antechamber where they could remove wet clothing and prevent cold and wet from reaching living quarters.

In January, a party of about thirty Inuit turned up and established friendly relations. The ship’s carpenter fashioned a wooden leg for a one-legged man. The Inuit came from a village of about one hundred who were living three kilometres away in a temporary village of eighteen snow huts. An Inuk named Ikmalick drew a remarkably accurate map of the whole Gulf of Boothia.

Travelling with various Inuit, James Ross made day trips along the coast by dogsled. He determined that, as the locals said, Boothia was not an island but a peninsula. In April and early May, he made several longer journeys. Later in May, he crossed what is now James Ross Strait and named King William Land, Victory Point and Cape Felix.

At Victory Point, Ross built a massive cairn. From the cape, the northern tip of King William Land, he looked out and marvelled at the heaviest pack ice he had ever seen, noting that lighter floes had been “thrown up, on some parts of the coast, in a most extraordinary and incredible manner.” This was the region where, in 1846, John Franklin would get trapped. Now, in 1830, magnetic readings told James Ross that he was within fifteen to twenty-five kilometres of the ever-shifting north magnetic pole. But he lacked the instruments to verify its location.

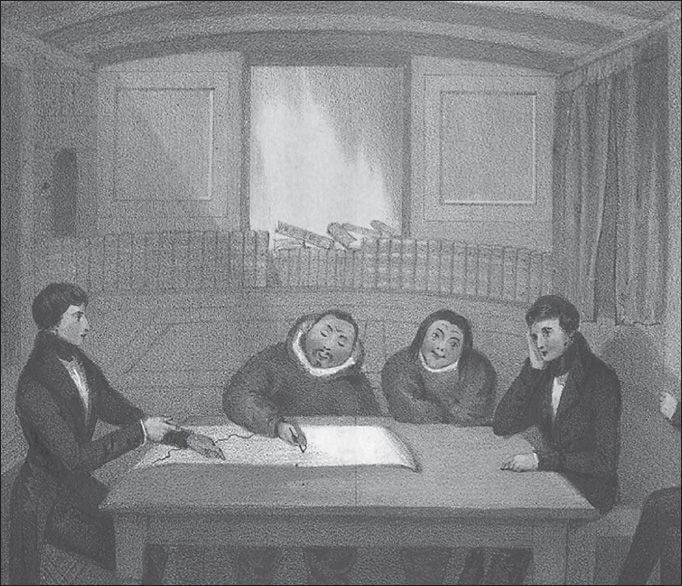

Ikmalick and Apelagliu were among the Inuit who sojourned near the bottom of Prince Regent Inlet. Here we have Ikmalick drawing a map of the Gulf of Boothia. John Ross painted the watercolour, which is reproduced here.

During the winter of 1830–31, with the Victory still trapped in the ice off the east coast of Boothia, Ross carried out endless observations and calculations. Late in the spring of 1831, hauling an enormous dip circle on his sled, and travelling with a party of Inuit, Ross followed his compass to the west coast.

On June 1, 1831, near a few abandoned huts, he made careful observations using that rudimentary dip circle. He kept moving until his dipstick indicated that he stood precisely atop the north magnetic pole. Here, having become the first man to “fix” the pole at a specific location, he built “a cairn of some magnitude.” Beneath it Ross buried a canister containing a written record.

In his journal, Ross wrote that he could have pardoned “anyone among us who had been so romantic or absurd as to expect that the magnetic pole . . . was a mountain of iron, or a magnet as large as Mont Blanc. But nature had here erected no monument to denote which spot she had chosen as the centre of one of her great and dark powers.” He turned to the half dozen men with him: “Amidst mutual congratulations, we fixed the British flag on the spot, and took possession of the North Magnetic Pole and its surrounding territory, in the name of Great Britain.”

James Clark Ross built his cairn at latitude 70°5´17˝ north and longitude 96°46´45˝ west. In 1998, a search expedition found it there in ruins, little more than a circle of stones. The north magnetic pole is long departed. As of 2015, the pole was in the Arctic Ocean (at 86°3´ north, 160° west), zigzagging towards Russia.

Now came one of those ordeals for which the Arctic is feared. Summer arrived but failed to melt the pack ice. The Victory could go nowhere. The sailors, bitterly disappointed, settled in for a third cold, dark winter. John Ross kept most of his men free from scurvy by ensuring that they ate an Inuit diet, featuring plenty of fat. The Inuit themselves had moved and did not return—another disappointment.

In January 1832, one man died, having caught a severe cold during a fishing expedition. All of the men were suffering. In the dead of winter, they began preparing to abandon ship. J. C. Ross supervised the loading of boats and provisions onto sledges, and late in April, the sailors began hauling these northward in relays towards Fury Beach, where they knew supplies remained. John Ross summarized from the ship on May 21, noting, “We had travelled three hundred and twenty-nine miles to gain about thirty in a direct line; carrying the two boats with full allowance of provisions for five weeks; and expending, in this labour, a month.”

Eight days later, the sailors hoisted the colours, drank a toast and abandoned the Victory to the ice. Man-hauling heavy sledges is known to be terrible work. With more than 240 kilometres still to go to Fury Beach, the exhausted men asked to abandon the sledges. John Ross “ordered the party to proceed, in a manner not easily misunderstood, and by an argument too peremptory to be disputed.”

The men reached Fury Beach on July 1, “worn out completely,” as John Ross admitted, “with hunger and fatigue.” They erected a timber dwelling, “Somerset House,” and repaired and rigged the three available boats. On August 1, with clear water at the beach, the party set out in the boats, carrying provisions for six weeks. Driven onto a rocky beach, they were marooned for six days beneath a cliff. Late in the month, they reached the mouth of Prince Regent Inlet, a sixty-five-kilometre-wide expanse with ice blocking the way out to the north.

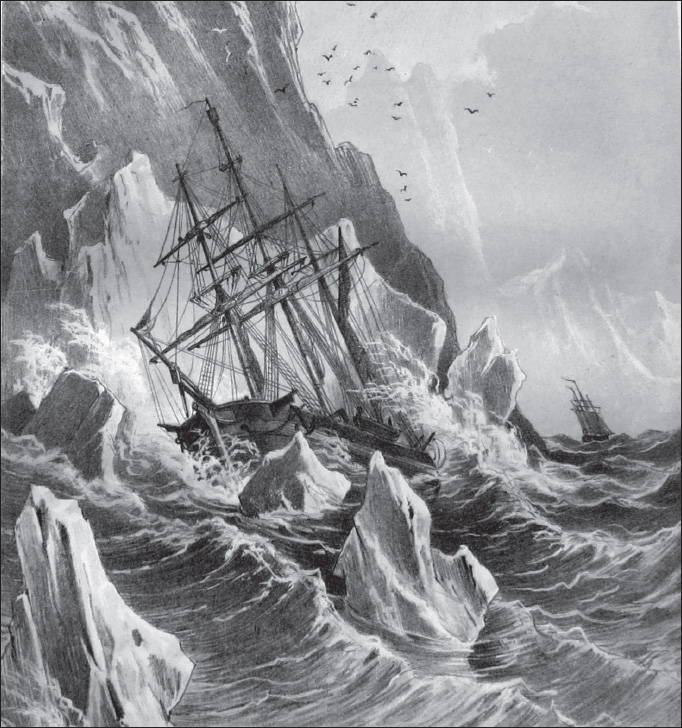

The wreck of HMS Fury in 1825, which left supplies on what has since been called Fury Beach, would prove to be the salvation of the 1830s expedition led by John Ross. Here the wreck is depicted in Arctic Expeditions from British and Foreign Shores, an 1877 book edited by David Murray Smith.

On September 25, the party turned around and, with ice appearing along the coast, started back towards Fury Beach. After reaching it on October 7, they began preparing to spend an unprecedented fourth winter in the Arctic. In January 1833, John Ross would write that, with ice and snow piled high around the rough house, “we have become literally the inhabitants of an iceberg.” The following month, one man died of scurvy. The Rosses worked on their journals, but most of the men “dozed away their time in the waking stupefaction which such a state of things produces.”

Late in April 1833, James Ross started carrying supplies forward fifty kilometres north, where the men had stored the boats. The party left Somerset House on July 8, with three of the sailors unable to walk and needing to be hauled. At the boats, gale-force winds pinned the men to the shore for another month. Finally, on August 14, a lane of water opened to the north. By eight the next morning, the party was underway in three boats. This time, the way forward remained relatively open.

The men crossed Prince Regent and continued eastward, camping from time to time. On the morning of August 26, off the north coast of Baffin Island near Navy Board Inlet, they spotted a ship that sent out a boat. John Ross asked the name of the vessel and was told: “The Isabella of Hull, once commanded by Captain Ross.” This extraordinary coincidence brought an enthusiastic welcome as sailors hung from the rigging and cheered the shipwrecked sailors aboard.

When John Ross landed in England on October 18, 1833, one newspaper reported: “The hardy veteran was dressed in sealskin trousers with the hair outwards, over which he wore a faded naval uniform, and the weather beaten countenances of himself and his companions bore evident marks of the hardships they had undergone.” Having survived more than four years in the Arctic, the Rosses were feted by King William IV. In October of 1834, James Clark Ross was promoted to post captain in recognition of his achievements—notably that of having pinpointed the elusive north magnetic pole.