11.

Two HBC Men Map the Coast

What was George Simpson thinking? The governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company scorned caprice and whimsicality. His contemporaries called him “the Little Emperor.” By June 1836, certainly, with sixteen years of dictatorship behind him, Simpson had earned his reputation as the Machiavelli of the fur trade. So when, at a meeting of governing council, he announced an Arctic expedition whose leadership would yoke his temperamental younger cousin, Thomas Simpson, with the “mixed-blood” veteran Peter Warren Dease, he undoubtedly thought the idea brilliant.

This was five years after James Clark Ross, at age thirty-one, had located the north magnetic pole. Like George Simpson himself, Thomas Simpson, not yet twenty-eight, had been born and raised in Dingwall, in northern Scotland. At King’s College, Aberdeen, he had earned a master of arts degree with first-class honours, winning an award in philosophy. He was fond of the outdoors and, after his older cousin George brought him into the HBC, he spent five years working as the governor’s secretary at Red River Settlement, the administrative centre of which was at Upper Fort Garry in the middle of present-day Winnipeg.

The younger Simpson was ambitious, competent and hard working. But he was also egotistical, outspoken and aggressively racist. At one point, he wrote that if smallpox thinned the Métis population, it “would be no great loss to humanity.” At another, he confessed that he felt “not the least sympathy with the depraved and worthless half breed population.” And again, speaking of native people, “for my part I owe them hatred and not pity.”

Thomas Simpson was brilliant and persevering, but also headstrong and racist. This posthumous portrait by George Pycock Green is held in the Baldwin Collection at the Toronto Reference Library.

An incident from around Christmas 1834 brought matters to a head. A Métis worker had requested a standard advance on his next season’s wages. Thomas Simpson had refused and insulted the man. When the worker answered in the same spirit, Simpson hit him with a poker, drawing blood. A mob gathered, warning that if Simpson was not handed over, or at least publicly flogged, they would destroy the HBC fort.

A priest defused the situation by paying off the offended worker and distributing ten gallons of rum and tobacco among those who had gathered. But George Simpson, himself no paragon of racial tolerance, could see that his ambitious young cousin needed to change his attitude, or at least learn to control his temper and keep his mouth shut.

Meanwhile, the HBC was under pressure to explore the North Country as part of its charter. The governor proposed to dispatch a two-part expedition to the Arctic coast to complete the coastal survey that Franklin and John Richardson had begun. The headstrong Thomas Simpson had been clamouring to lead this sortie. But in 1836, the governor decided to make him second-in-command to Peter Warren Dease, who had won praise for assisting Franklin on his second expedition.

At forty-eight, Dease had worked in the fur trade for thirty-five years. He was the son of an Irish immigrant administrator and a Mohawk woman from Caughnawaga (Kahnawake), near Montreal, and so, strictly speaking, was himself “a half breed.” George Simpson knew that Dease had been among the Métis Nor’Westers who, in 1820, ambushed the HBC man Colin Robertson and carried him off to Lower Canada.

Yet since the fur-trade amalgamation that Simpson had engineered, Dease had risen steadily through the HBC ranks to become a highly respected chief factor. To John Franklin, before he embarked on his second expedition, the governor had written urging “that you do not part with Mr. Dease under any circumstances.” Dease, he added, was “one of our best voyageurs, of a strong, robust habit of body, possessing much firmness of mind joined to a great suavity of manners, and who from his experience in the country . . . would be a most valuable acquisition to the party in the event of its being unfortunately placed in trying or distressing circumstances.”

Dease was also a “most amiable, warm-hearted, sociable man,” according to one of his subordinates. While in charge of the profitable New Caledonia District, he hosted feasts, organized game nights and led musical soirees at which he played fiddle and flute “remarkably well.” Simpson knew, also, that Dease had taken a Métis woman as his country wife, and that together they had half a dozen children. On June 21, 1836, both Dease and Thomas Simpson were present when, at a meeting of the HBC council at Norway House, just north of Lake Winnipeg, George Simpson announced his decision. He must have reasoned that the mature, unflappable Dease would have a beneficial effect on his impulsive, hard-driving cousin.

From Norway House, having received their marching orders, Peter Warren Dease and Thomas Simpson initially went their separate ways. Late in the summer, Dease led a small group of men northwest along a well-known fur-trade route, a succession of rapids and portages, to Fort Chipewyan on Lake Athabasca. Thomas Simpson, meanwhile, remained at Fort Garry in Red River Settlement, where he applied himself to physical conditioning while mastering surveying and navigation.

Early in December, young Simpson set out with a few men to join Dease. He covered 2,043 kilometres in sixty-three days, including eighteen given over to stops, and arrived at Fort Chipewyan on February 1, 1837. As the winter unfolded, Dease supervised the construction of several boats, including three for the expedition. One of these, the massive Goliath, would sail the rough waters of Great Bear Lake, still farther north, where men would build a winter dwelling. The other two, Castor and Pollux, were small enough for hauling—each twenty-four feet long and six feet wide—and featured washboards to keep waves from rolling over the gunwales. He had all three ready and tested by the end of May.

From Fort Chipewyan on June 1, accompanied by Dene hunters, the explorers started down the Slave River. Over the next four months, they would travel non-stop. They would reach the Arctic coast, and then retrace and radically extend the mapping that Franklin and Richardson had accomplished on their second expedition. Hampered by ice, especially on Great Slave Lake, they reached Fort Resolution in ten days—they were now roughly one-third of the way to Great Bear Lake. They set out again on June 21, and were soon canoeing down the Mackenzie River.

Battling mosquitoes, the expedition passed Fort Simpson and reached Fort Norman on July 1. Dease sent four HBC men, plus a number of guides and hunters, east up the Great Bear River to begin building winter quarters (Fort Confidence) on Great Bear Lake. With a dozen men, Dease and Simpson continued north down the Mackenzie, reaching the coast on July 9. In their two boats, they started west, mostly rowing, and battling fog and ice.

They met a few small groups of friendly Inuit as they retraced Franklin’s route. On July 23, they reached Return Reef, where that naval officer had turned back. In 1826, coming from the west in a Royal Navy ship, Captain Frederick Beechey had navigated the stretch eastward from Icy Cape, Alaska, to Point Barrow. Now, in 1837, Dease and Simpson were bent on closing the gap between Return Reef (Franklin’s farthest) and Point Barrow, a distance of 280 kilometres. This would complete the survey of the western end of the coastal channel. But on July 31, having accomplished two hundred kilometres, they hit a solid barrier of ice that precluded further progress. Dease agreed to guard the boats while Simpson proceeded on foot with five men and a collapsible canvas canoe. These six travelled quickly until they reached “Dease Inlet,” which was too broad and rough for their portable craft.

But here, by chance, they encountered a few Inuit who were willing to lend them an umiak, a traditional craft that could carry half a dozen people. In this, they crossed the inlet and continued west until, on August 4, 1837, they reached Point Barrow. Later, apparently forgetting how Dease had got him down the Mackenzie and then to within five days of that location, Simpson would write to his brother, that “I, and I alone, have the well-earned honour of uniting the Arctic to the great Western Ocean, and of unfurling the British flag on Point Barrow.”

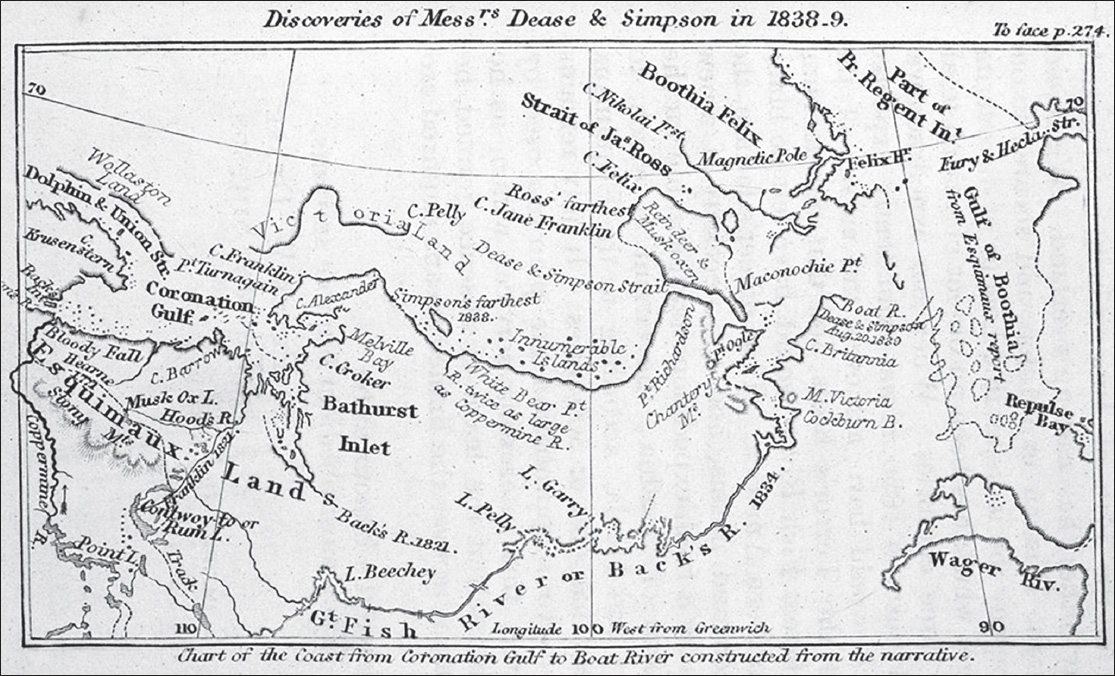

This early map shows that confusion remained even after the 1838–39 expedition of Peter Warren Dease and Thomas Simpson.

The return journey unfolded without incident. On September 25, the men reached Great Bear Lake and the site of their winter quarters, still under construction. They had completed the first half of their two-part expedition. They lived in tents for the next month, when finally they moved into the wooden Fort Confidence. Now came a fierce Arctic winter, with short days, long nights, blowing snow and temperatures hovering between thirty and forty degrees below zero Celsius. The men turned trees into firewood, hunted caribou and muskox, and did plenty of ice fishing. One man got lost and died in the snow while bringing mail from Fort Simpson.

Near the end of March, Thomas Simpson located a viable route eastward to the Coppermine River. Early in April, he deposited six sledges worth of supplies on a tributary called the Kendall. By mid-May, the men were ready to attempt part two of their expedition: the eastern leg. In 1826, while Franklin had journeyed west with Tattannoeuck, John Richardson had surveyed the coast eastward from the mouth of the Mackenzie to the mouth of the Coppermine. On their first expedition, which had ended so disastrously, Franklin and Richardson had pushed eastward beyond the Coppermine to Point Turnagain on Kent Peninsula.

Eight years later, still farther east, George Back had descended to the Arctic coast down the Great Fish River, now called the Back River, and explored Chantrey Inlet and Montreal Island as far north as Ogle Point. Beyond that, the Arctic map grew vague. In 1830, James Clark Ross had visited the northern tip of King William Island (Cape Felix) by crossing ice from the west coast of Boothia Peninsula. But in fog and snowy weather, peering southward, he had failed to discern Rae Strait. Instead, surmising that the two land masses, the island and the peninsula, were connected by land, he drew a tentative map linking them across the bottom of a non-existent “Poctes Bay.”

Eight years later, the geography of the area remained unclear. With the second part of their expedition, Dease and Simpson wanted to clarify matters and fill in the blank stretches. They proposed to travel from Franklin’s Point Turnagain to Back’s Ogle Point, a distance of at least 320 kilometres. The first time they tried, during the summer of 1838, they ran up against heavy ice. Halted near Point Turnagain, Simpson made a final push on foot. Accompanied by the two hunters and five HBC men, he trekked along the ice-choked channel to Cape Alexander, at the northeast corner of Kent Peninsula.

Some men might have decided that adding another 140 kilometres to the Arctic chart represented success. Thomas Simpson was not one of them. Instead of heading for home, as the men had fondly imagined they might, they found themselves preparing for another winter. Again they reduced trees to firewood. Again they set their fishing nets and hired locals to help with the hunting. Again, they insulated their lodgings as best they could.

This second winter proved harder than the first. Two native girls were murdered and the hunters grew fearful, afraid to head out with their usual daring. The fishing was less successful and the caribou had migrated south. With many native people facing possible starvation, Dease had to dispense meat originally intended to make travel-ready pemmican.

Ouligbuck had served with Tattannoeuck on Franklin’s second overland expedition. Lieutenant George Back drew this sketch, reproduced here courtesy of Kenn Harper.

Early in the spring came one positive development—the arrival of Ouligbuck, an outstanding Inuit hunter and interpreter who had served on Franklin’s second expedition, mainly with John Richardson. Born around 1800, Ouligbuck was a younger friend of Tattannoeuck, who had brought him along from their home at Churchill. From the mouth of the Mackenzie River, when Tattannoeuck travelled west with Franklin, Ouligbuck had journeyed east with John Richardson.

He “was not of much use as an interpreter,” Richardson wrote later, “for he spoke no English; but his presence answered the important purpose of showing that the white people were on terms of friendship with the distant tribes of Esquimaux.” Richardson added that, “as a boatman [Ouligbuck] was of the greatest service, being strongly attached to us, possessing an excellent temper, and labouring cheerfully at his oar.” His “attachment . . . was never doubtful, even when we were surrounded by a tribe of his own nation.”

In 1827, having completed that expedition, Ouligbuck had returned to the HBC fort at Churchill, where he worked as a jack-of-all-trades. He harpooned whales, made canoe paddles and even weeded turnips. He also improved his English. In 1830, while waiting to join an HBC expedition into Ungava, Ouligbuck worked farther south, at Moose Factory. That September, he played a key role in opening trade at Fort Chimo (now Kuujjuaq), where he remained for the next six years.

The HBC summoned Ouligbuck to accompany the coastal expedition led by Dease and Simpson. With his wife and children, the Inuk reached Fort Confidence on April 13, 1839. Given his much improved English, and his exceptional abilities as a hunter, Thomas Simpson dubbed him a “valuable and unhoped for acquisition.”

The month of May was colder than usual, which delayed the spring melt on the rivers and lakes. But then June brought warmer weather. Peter Dease took to breaking out his fiddle, and soon the men were ready to set out once more. This time, they hoped to extend their coastal survey at least to Ogle Point. On June 15, 1839, the men left Fort Confidence and made their way to the boat depot in four days. They ran the rapids down the Coppermine to Bloody Falls, where they retrieved their cached supplies.

On the twenty-fifth, Ouligbuck brought two Inuit back to camp, one of whom was elderly. They could provide only local information, but the old man, observing that Dease desperately needed new boots, promised to make him a pair for pick-up when he returned that way in September. The explorers ran the river to the sea, where ice kept them from leaving until July 3. Then they set out and at first made fitful progress.

Halted by ice just east of Port Epworth, the men spent four days building a fifteen-foot-long cairn. They reached Franklin’s Point Turnagain on July 20, three weeks earlier than the previous year, and Cape Alexander on the twenty-eighth. Now they began charting new territory, pushing east through a scattering of islands until, on August 10, they reached Adelaide Peninsula and the western end of what would soon be called Simpson Strait.

They continued east, and two of the voyageurs, who had descended the Great Fish River with George Back in 1834, thought they recognized Ogle Point. They confirmed this about fifty kilometres south when, on August 16, they led the way on Montreal Island to a cache deposited by that earlier expedition. The men managed to salvage some aging chocolate, and the leaders preserved some gun powder and fish hooks “as memorials of our having breakfasted,” Simpson wrote, “on the identical spot where the tent of our gallant, though less successful, precursor [George Back] stood that very day five years before.”

Having reached Chantrey Inlet, Dease and Simpson had technically attained their objective. They could have headed for home. But the weather was fine, they had plenty of food and they agreed to press eastward to determine whether Boothia Felix was a peninsula or an island divided from the mainland by a strait leading to Lord Mayor Bay. They crossed Chantrey Inlet to Cape Britannia and then pushed north until headwinds forced them ashore. Early on August 20, they reached the mouth of a small river. They named it Castor and Pollux, after their two boats, and built another massive cairn, this one ten feet high. Simpson and Dease walked five or six kilometres farther north to a vantage point and stood gazing out.

Simpson believed—wrongly—that, just to the north of where he stood, a strait led eastward into Hudson Bay. “The exploration of such a gulph, to the Strait of the Fury and Hecla, would necessarily demand the whole time and energies of another expedition, having some point of retreat much nearer to the scene of operations than Great Bear Lake; and we felt assured that the Honourable Company, who had already done so much in the cause of discovery, would not abandon their munificent work till the precise limits of this great continent were fully and finally established.”

Simpson had the details wrong. He surmised that a navigable strait ran west-east rather than south-north. But certainly he was bent on leading another expedition to this area—one that would have enabled him to find the as-yet-undiscovered Rae Strait, which runs between Boothia Peninsula and King William Island. “It was now quite evident to us,” Simpson wrote, “even in our most sanguine mood, that the time was come for commencing our return to the distant Coppermine River, and that any further foolhardy perseverance could only lead to the loss of the whole party.”

Despite headwinds, the expedition made steady progress. Back through Simpson Strait, the men hugged the south coast of King William Island. When, on August 25, they found it veering northward, they stopped and built a fourteen-foot-high cairn at “Cape John Herschel.” Proceeding west through Queen Maud Gulf, they reached Melbourne Island and then, instead of retracing Kent Peninsula, continued west along the south coast of Victoria Island, identifying and naming Cambridge Bay.

They crossed Dease Strait to Cape Barrow on September 10, and from there battled snow showers. “We pursued our way unremittingly night and day, fair and foul,” Simpson wrote, “whenever the winds permitted; and on the 16th, in a bitter frost, and the surrounding country covered with snow, we made our entrance into the Coppermine, after by far the longest voyage ever performed in boats on the Polar Sea, the distance we had gone not being less than 1,408 geographical, or 1,631 statute miles [2,625 kilometres].”

On reaching Bloody Falls, Dease wrote, “I found to my surprise . . . that the old man from whom I bespoke a pair of Boots, has punctually performed his promise. They were tied at the End of a Pole and put up in a Conspicuous place with some Seal Skin line.” The men left one boat here, along with some supplies that would be useful to the Inuit, and tracked or towed the other to the previous boat depot. In his journal, Dease mentions several occasions along the way when Ouligbuck or another hunter shot a welcome buck.

Dease also offers an amusing anecdote about how, while helping several men haul the boat upstream, Ouligbuck got stuck halfway up a steep cliff, its rocks coated with ice and hung with icicles. After scuttling along after a smaller, lighter Dene hunter, he “got upon a narrow ledge of rocks, beyond which he thought it dangerous to proceed, and equally so in his now alarmed mind to retrace his way back. He therefore laid down and began to bawl out lustily for assistance, which was rendered him after the Indian had run about 1/2 mile after the boat. Some of the men went back and with a line extricated him from his awkward position, to his great joy, at finding himself again in safety.”

After a final trek over snow-covered ground, the men arrived at Fort Confidence on the evening of September 24, 1839. Two days later, they were beating south across Great Bear Lake. And Governor George Simpson stood vindicated. With Peter Warren Dease handling logistics and keeping the crew well supplied and happy in their work, and Thomas Simpson driving obsessively to achieve geographical objectives, the expedition had exceeded expectations, accomplishing the longest boat voyage yet in what was essentially the Arctic Ocean. But now the co-leaders went separate ways.

Dease spent the winter at Fort Chipewyan. In August 1840, he formally married Elizabeth Chouinard, his Métis country wife of many years, and the mother of his eight children. Both Dease and Simpson had been granted a pension of one hundred pounds a year by Queen Victoria “for their exertions towards completing the discovery of the North West Passage.” Dease undertook his first-ever trip to London, mainly to address vision problems, and was honoured at HBC headquarters. Writing from York Factory, the relatively progressive Letitia Hargrave reported hearing a rumour that Dease would be knighted. In the charming parlance of the day, she noted that this “diverts the people here as they say Mrs. Dease is a very black squaw & will be a curious lady.” Later she added that Dease, “with that modesty which was part of his nature,” declined the knighthood.

Dease remained on medical furlough until he retired officially in 1843. By then he had settled on a farm near Montreal, where, according to another chief factor, James Keith, he was governed “by his Old Squaw & Sons. She holding the Purse strings & they spending the Contents par la Porte et par les fenetres.” There he remained, comfortable and respected, until, having outlived three of his four sons, Peter Warren Dease died in 1863 at age seventy-five.

Thomas Simpson, meanwhile, spent the late autumn of 1839 at Fort Simpson, where he completed his narrative of the expedition for publication. He had sent a letter to his cousin, Governor George Simpson, seeking permission to lead an expedition to locate the final link in the Northwest Passage. To his brother Alexander, who was working for the HBC at Moose Factory, he wrote, “Fame I will have but it must be alone.” He would achieve more, he wrote, alluding to Dease, when he was free of “the extravagant and profligate habits of half-breed families.”

On December 2, with the Mackenzie River frozen solid, Simpson set out travelling south by dogsled. He reached Red River Settlement on February 2, 1840, having travelled more than 2,800 kilometres. Back in October, Simpson had written to his cousin, the governor, and to the London committee of the HBC, proposing to investigate the area he had just visited. He was confident that there he would discover that elusive final link.

Simpson intended to use George Back’s old base at Fort Reliance, and to descend the Great Fish (Back) River. He would return via the same route, or else, if he located an eastward strait, head south through Fury and Hecla Strait to York Factory. Again, this plan would have failed in its particulars but would undoubtedly have led him to discover Rae Strait. He would have corrected the map that, a few years later, in 1846, would encourage Franklin to turn west when he approached Cape Felix, and so to get trapped in the perennial pack ice flowing south from the polar ice cap.

At Fort Garry, the high-strung Simpson waited impatiently for a response from either the governor or from England. He received nothing with the next two mail packets, which arrived on March 24 and on the second day of June. On June 3, Thomas Simpson began preparing his proposed expedition, arranging for boats and supplies. He did not know it, but on that same day, the London committee approved his proposal. On June 4, George Simpson drafted a letter to him, adding detailed instructions. That was also the day Thomas set off southward from Fort Garry, bent on travelling via Minnesota to England to convince his HBC superiors to make a decision they had already made.

Thomas Simpson set out with two Métis. Next day, this trio joined up with a larger group of Métis. On June 10, Simpson insisted on pushing ahead with four men. What happened next has spawned no end of speculation. Certain it is that Thomas Simpson and two fellow travellers ended up dead. According to one version, Simpson became unhinged, shot the two Métis without reason and then committed suicide. According to another, more fanciful rendition, one Métis believed Simpson was carrying the secret to the Northwest Passage and, while trying to steal it, provoked a shootout. A third scenario, still more ludicrous, presented George Simpson as having masterminded the killing so that he could claim the glory of discovering the final link.

A friend of Thomas Simpson, Chief Factor John Dugald Cameron, offered the only credible explanation in a letter to James Hargrave of York Factory: “I am sure there must have been a quarrel between him and the others before the work of blood began. Mr. Simpson was a hardy active walker. Anxious to make an expeditious journey, he would have found fault with the slow pace of his fellow travellers.” He would have made harsh remarks, Cameron added, prompting fellows as fiery as himself, and who had no great love for him, to respond in kind. This “would have soon led into quarrels—and from quarrels to the work of death.”

The man’s bigotry, impatience and egotism proved his undoing. If Thomas Simpson had lived to lead his 1841 expedition, he would have found Rae Strait—a discovery that would almost certainly have precluded the tragedy that engulfed the Franklin expedition. The fact remains that, in concert with Peter Warren Dease, he added roughly six hundred kilometres to the map of the southern channel of the Northwest Passage. He also identified the area where crucial discoveries were yet to be made. And when, in 1854, John Rae embarked on his last great Arctic expedition, he started its crucial final leg from the mouth of the Castor and Pollux River, where Simpson and Dease had left off.