15.

Voyagers Find Graves on Beechey Island

Late one morning in August 1850, while talking on the bow of a ship trapped in the ice off Beechey Island, speculating about what route John Franklin might have taken, an American searcher, Elisha Kent Kane, was startled by the sound of a voice yelling, “Graves!” A sailor was stumbling breathless across the ice from shore. “Graves!” the man shouted. “Franklin’s winter quarters!”

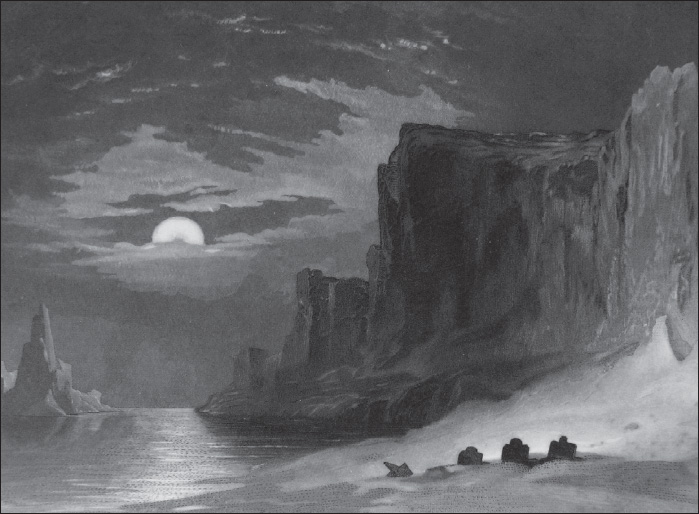

Searchers had found what has since become the most visited historical site in the Arctic—the graves of the first three men to die during Franklin’s final voyage. At this desolate spot in 1846, while still hoping to discover a northwest passage, the long-winded Franklin would have conducted sonorous funeral services for the dead men. Now, four years later, the Philadelphia-born Kane led searchers in scrambling across the ice and up a short slope to the makeshift cemetery. “Here, amid the sterile uniformity of snow and slate,” he wrote later, “were the head-boards of three graves, made after the old orthodox fashion of gravestones at home.”

Drawn by James Hamilton from a sketch by Elisha Kent Kane, this is a romanticized representation of the Beechey Island gravesite. In 1850, Kane was present at the discovery of the site.

Born in 1820, the oldest son of a patrician family based in Philadelphia, then called “the Athens of America,” Elisha Kent Kane trained as a doctor. Despite recurring illness and health problems—his heart condition would kill him within a decade—he became what today we would call an extreme adventurer. While still in his twenties, he descended into a volcano in the Philippines, infiltrated a company of slave traders in West Africa and narrowly survived a stabbing during hand-to-hand combat in the Sierra Madre.

While sailing as an assistant surgeon in the American Navy, ranging from the Mediterranean to South America, Kane felt revolted by the brutality of shipboard discipline. After seeing one man flogged three times and another receive fifty lashes, he sought and gained a transfer to the United States Coast Survey, which had been created to map harbours and coastlines.

This government-run department had become the leading proponent of “Humboldtean science” in America. At the turn of the nineteenth century, Alexander von Humboldt had established a new model for geographical studies. While exploring the interior of South America, Humboldt had forged a stellar reputation as a scientific truth-seeker who would risk his life to advance the causes of science and humanity.

By entering the Coast Survey, as David Chapin observed in Exploring Other Worlds, Kane found a model of exploration worth emulating. He liked the idea of men working outdoors, subordinating individual interests to the common good, and sleeping in tents for weeks at a time. Assigned to the steamer Walker, Kane helped survey the southeast coast of North America.

By January 1850, when he sailed into Charleston, South Carolina, Kane had become keenly interested in the search for Sir John Franklin. The previous April, Lady Franklin had written to American president Zachary Taylor, asking that the United States “join heart and mind in the enterprise of snatching the lost navigators from a dreary grave.” A New York shipping magnate, Henry Grinnell, perceived that the search for Franklin could be combined with a quest to test a scientific hypothesis attracting attention among American geographers—the idea that, at the top of the world, there existed the Open Polar Sea, teeming with fish and mammals.

After exchanging letters with Lady Franklin, Grinnell decided to sponsor an American search expedition. To keep expenses within reason, he needed the U.S. Navy to supply manpower and provisions—and so he told Jane Franklin. In December 1849, this persuasive woman wrote again to President Taylor. She stressed that the lost sailors, “whether clinging still to their ships or dispersed in various directions, have entered upon a fifth winter in those dark and dreary solitudes, with exhausted means of sustenance.”

In a January newspaper, Elisha Kent Kane read that President Taylor had brought Lady Franklin’s request to Congress, and asked that the U.S. Navy supply Grinnell with two vessels. Soon afterwards, while still aboard the Walker, Kane wrote a letter to the secretary of the Navy, volunteering to serve with any Arctic search expedition that might be mounted. When he received no reply, the young officer abandoned hope.

But then, on Sunday, May 12, while swimming in the Gulf of Mexico at Mobile, Alabama, Kane was called ashore to receive a surprising telegram. It was “one of those courteous little epistles from Washington,” he would write, “which the electric telegraph has made so familiar to naval officers.” It detached him from the Coast Survey and ordered him “to proceed forthwith to New York, for duty upon the Arctic Expedition.”

Kane exulted in this development. His mother was less enthusiastic, but recognized that “it is vain to grieve. Elisha cannot live without adventure.” His father, a judge and backroom politician, wrote: “I cannot rejoice that he is going on this expedition; his motive is most praiseworthy, but I think the project a wild one, and I fear inadequacy in outfit. I wish most sincerely that Sir John Franklin was at home with his wife again, leading dog’s lives together as they used to do . . . But it is as it is and we must make the best of it:—Oh! this Glory! when the cost is fairly counted up, it is no such great speculation after all.”

As he travelled to New York City, Kane never doubted he would join one of two impressive ships. After all, the lost vessels of Sir John Franklin, the Erebus and the Terror, weighed 370 and 326 tons respectively, and could together accommodate more than 130 men. Nor was he alone in his expectations. Another officer who would sail with the expedition, Robert Randolph Carter, had just left the Savannah—a massive 1,726-ton ship with a complement of 480 men. This was the kind of vessel, surely, that would lead the United States Grinnell Expedition in Search of Sir John Franklin.

But on Tuesday, May 21, when Kane reported at the Brooklyn Naval Yard, he discovered to his dismay that the grandly named Grinnell expedition comprised two vessels so small that only their masts showed above the edge of the wharf. The flagship Advance weighed only 146 tons, and the Rescue just 91. Expected to carry a total of thirty-three men between them, these tiny “hermaphrodite brigs”—square-rigged foremast, schooner-rigged mainmast—were designed for manoeuvrability and speed, but lacked anything resembling naval trim. Half-stowed cargo cluttered their decks, and Kane felt he “could straddle from the main hatch to the bulwarks.” The ships looked “more like a couple of coasting schooners than a national squadron bound for a distant and perilous sea.”

Kane soon realized that Henry Grinnell and expedition leader Edwin De Haven had worked hard to prepare the ships for Arctic service. The eighty-eight-foot-long Advance, on which Kane would sail as surgeon, had been doubly sheathed in thick oak planking and reinforced from bow to stern with sheet-iron strips. Seven feet of solid timber filled the space behind the bow. The rudder could be hauled aboard, and the winch, capstan and windlass “were of the best and newest construction.” Kane also found the library well stocked, especially with books on polar exploration.

The Navy-supplied equipment impressed him less. The antiquated stoves had been stowed deep in the hold, and the firearms, mostly ball-loading muskets, proved a “heterogeneous collection of obsolete old carbines, with the impracticable ball cartridges that accompanied them.” Kane worried that the food supplies, while possibly adequate for the projected three-year voyage, would not prove varied enough to ward off scurvy.

With the “zealous aid” of Mr. Grinnell, who provided the funds, Kane spent several hours dashing around New York City, purchasing thermometers, barometers and magnetometers. These “would have been of use to me if they had found their way on board,” he wrote later. From home, where he had briefly stopped, he had brought a few books, some coarse woollen clothing and a magnificent buffalo-skin robe from “the snow drifts of Utah,” a parting gift from his brother, Thomas, later a hero in the American Civil War.

On the Advance, Kane would share a below-decks cabin, smaller “than a penitentiary cell,” with De Haven and the other two officers. This dank accommodation contained camp stools, lockers and berths for four men, as well as a hinged table and a “dripping step-ladder that led directly from the wet deck above.” Kane shielded his berth—“a right-angled excavation” six feet long, thirty-two inches wide and less than three feet tall—with a few yards of India rubber cloth.

Inside, on tiny shelves, he placed his books and a reading lamp. Then, using nails, hooks and string, he suspended a few items along the wall: watch, thermometer, inkbottle, toothbrush, comb and hairbrush. When, with all this accomplished, Kane “crawled in from the wet, and cold, and disorder of without, through a slit in the India-rubber cloth, to the very center of my complicated resources,” he revelled in the comfort he had manufactured. And at 1:00 p.m. on May 22, 1850, the day after Elisha Kent Kane reached New York City, the Advance cut loose from the “asthmatic old steam-tug” that had towed it out of the Brooklyn Navy Yard and began its long voyage.

As the Advance sailed north, Kane battled seasickness and perused the analytical writings of Matthew Fontaine Maury, wrestling with ideas that the theoretician would later incorporate in his 1855 classic, The Physical Geography of the Sea. After years of study, Maury had become the leading exponent of the popular theory that, at the top of the world, there lay the Open Polar Sea.

Whales sometimes carried harpoons in their backs from the Bering Strait in the west to Baffin Bay in the east. Because these mammals cannot travel such a distance under ice, Maury deduced that “there is at times, at least, open water communication through the polar regions between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.” And so he revived the theory that the Open Polar Sea lay beyond a northern ring of ice, an idea with roots in the sixteenth century.

Elisha Kent Kane, age thirty-five, with telescope.

Captain De Haven, a veteran sailor, dreaded writing reports and found no excitement in Maury. But the imaginative Kane showed such a passion for the scientist’s musings that when he floated the idea of writing a book about the voyage, De Haven hailed the idea. Night after night, while others slept, Kane huddled in his berth and scratched away by lamplight, bent on producing “a history of the cruise under the form of a personal narrative.”

By the time he reached Greenland, Kane had sailed past his first iceberg—a gigantic cube coated with snow that resembled “a great marble monolith, only awaiting the chisel to stand out . . . a floating Parthenon.” He had watched his first school of whales tumbling like porpoises around the vessel—“great, crude, wallowing sea-hogs, snorting out fountains of white spray.” And he had marvelled at the continuous sunlight of northern latitudes in summer: “The words night and day begin to puzzle me, as I recognize the arbitrary character of the hour cycles that have borne these names.”

On July 3, 1850, after resuming the voyage and passing through what Kane described as “a crowd of noble icebergs,” the two American ships encountered a berg-dotted expanse of pack ice. Prevailing currents usually pushed this so-called Middle Ice to the west, opening a channel along the Greenland coast. Whalers would follow this laneway as far north as Melville Bay—little more than an indentation—and then swing westward, crossing Baffin Bay north of the Middle Ice, through the relatively ice-free North Water.

Occasionally, to save valuable summertime weeks, voyagers tried to cross Baffin Bay by threading their way through the Middle Ice. In 1819, Edward Parry had succeeded in this; fifteen years later, he wasted two months trying. Now, in July 1850, Kane described the “vast plane of undulating ice” as creating an unspeakable din of crackling, grinding and splashing: “A great number of bergs, of shapes the most simple and most complicated, of colours blue, white, and earth-stained, were tangled in this floating field.” One evening, while standing on deck, he counted 240 icebergs “of primary magnitude.”

By mid-August, the Americans understood that they would have to winter, as Kane put it, “somewhere in the scene of Arctic search.” On August 19, as the Advance neared the entrance to Lancaster Sound, its sailing master spotted two British vessels following in the ship’s wake. Within four hours, the larger of the two drew alongside. It proved to be the Lady Franklin, engaged in the Franklin search under whaling captain William Penny. He, too, had run into problems in Melville Bay. Before sailing past the slower Advance, he reported that a four-vessel British expedition led by Captain Horatio Austin had recently passed that way, and also the provision ship North Star.

A couple of nights later, while sailing through Lancaster Sound, driving before a strong wind and taking water at every roll, the Americans overtook a different British vessel. This small schooner, towing a launch and “fluttering over the waves like a crippled bird,” proved to be the Felix. Kane watched as “an old fellow, with a cloak tossed over his night gear, appeared in the lee gangway, and saluted with a voice that rose above the winds.” Two decades before, John Ross had been shipwrecked and survived four winters in the Arctic. Now he roared joyfully: “You and I are ahead of them all!”

Ross came on deck, a vigorous, square-built man looking younger than his seventy-three years, and reported that Austin’s four-boat squadron had taken refuge in various bays, and that Penny was lost in the gale. At thirty, Kane knew enough Arctic history to appreciate the encounter—to delight in meeting John Ross near Admiralty Inlet, where seventeen years before the old seadog had contrived to escape an icy incarceration. Kane also marvelled that, despite opposition and even ridicule, Ross had sailed in search of his old friend in “a flimsy cockle-shell, after contributing his purse and his influence.”

On August 25, having fallen behind its partner ship, the Rescue, the Advance approached Cape Riley. From the deck, the Americans spotted two cairns, the larger marked with a flagstaff. They landed and, in the larger cairn, found a tin canister containing a note. Two days before, the British captain Ommanney had called there with the Assistance and the Intrepid, both from Austin’s four-ship squadron. He had discovered traces of a British encampment nearby, and noted that similar findings had been reported on nearby Beechey Island, at the entrance to Wellington Channel.

Later, in his book, Kane would suggest that Ommanney had suppressed a significant aspect of his landing: “Our consort, the Rescue, as we afterward learned, had shared in this discovery, though the British commander’s inscription in the cairn, as well as his offi-cial reports, might lead to a different conclusion. [The Rescue’s] Captain Griffin, in fact, landed with Captain Ommanney, and the traces were registered while the two officers were in company.” To this theme—the exclusive nationalism of the imperial British—the proudly American Kane would return.

Now, he inspected Cape Riley, notebook in hand. He identified five distinct “remnants of habitation”—four circular mounds of crumbled limestone, clearly designed as bases for tents, and a fifth such enclosure, larger and triangular in shape, whose entrance faced south towards Lancaster Sound. He also found large square stones arranged to serve as a fireplace and, on the beach, several pieces of pinewood that had once formed part of a boat. In Kane’s view, the evidence was meagre but conclusive: “All these speak of a land party from Franklin’s squadron.”

Next morning, the Advance sailed on towards Beechey Island, which “rose up in a lofty monumental block” of limestone, and which Kane insisted on identifying as a promontory or peninsula, because a low isthmus linked it to the much larger Devon Island. By August 27, five vessels under three commanders—William Penny, John Ross and Edwin De Haven—stood anchored within a few hundred metres. Not far from Beechey, Penny had discovered some additional traces of Franklin’s expedition—tin canisters with the manufacturer’s label, scraps of newspaper dated 1844 and two pieces of paper bearing the name of one of Franklin’s officers.

After breakfast, Kane and De Haven visited Penny’s ship, HMS Lady Franklin. On the deck, together with John Ross and Penny himself, they stood discussing how best to cooperate in continuing the search. Penny sketched out a rough proposal. He would search to the west. Ross would cross Lancaster Sound to communicate with the Prince Albert and prevent her from sailing south unnecessarily; and the Americans, with whom he had already consulted, would proceed north through Wellington Channel.

With this agreed, Ross left to return to the Felix. Kane was talking with the veteran Penny, who had speculated in print about the existence of the Open Polar Sea, when he heard a yell and saw a seaman hurrying across the ice. The sailor shouted against the noise of the wind and the waves: “Graves, Captain Penny! Graves! Franklin’s winter quarters!”

The officers debarked onto the ice to meet the messenger. After responding to questions as best he could, the seaman led the way onto Beechey Island and along a ridge to three headboards and graves, their mounds forming a line facing Cape Riley. The boards bore inscriptions declaring them sacred to the memories of three sailors—W. Braine of the Erebus, who died April 3, 1846, at age thirty-two; John Hartnell of the Erebus, no date specified, dead at age twenty-three; and John Torrington, “who departed this life January 1st, A.D. 1846, on board of H.M. Ship Terror, aged 20 years.” In describing this scene, Kane drew attention to the words “on board.” He added: “Franklin’s ships, then, had not been wrecked when he occupied the encampment at Beechey.”

The excitement of this discovery of graves would be felt down through the decades. Now, on August 27, 1850, Elisha Kent Kane copied the inscriptions and sketched the three graves against the desolate landscape. He then scoured the area, which abounded in fragmentary remains—part of a stocking, a worn mitten, shavings of wood, the remnants of a rough garden. A few hundred metres from the graves, he came upon a neat pile of more than six hundred preserved-meat cans. Emptied of food, these had been filled with limestone pebbles, “perhaps to serve as convenient ballast on a boating expedition.”

Countless other indications, including bits and pieces of canvas, rope, sailcloth and tarpaulins, as well as scrap paper, a small key and odds and ends of brass work, testified that this was a winter resting place. Nobody turned up any written documents, however, nor even the vaguest hint about the intentions of the party. Kane judged this remarkable—“and for so able and practiced an Arctic commander as Sir John Franklin, an incomprehensible omission.”

Others, given the benefit of hindsight and the accretion of evidence, have wondered whether Franklin was as competent as some of his contemporaries believed. In 1850, Kane noted only that it was impossible to stand on Beechey without forming an opinion about what had happened to the British expedition. Before offering his own, he reviewed the incontestable facts. During the winter of 1845–46, the Terror had wintered there. She kept some of her crew on board. Some men from the Erebus were also there. An organized party had taken astronomical observations, made sledges and prepared gardens to battle scurvy.

Beyond this lay speculation. Kane inferred the health of the expedition to be generally satisfactory, as only three men had died out of nearly 130. He puzzled over the abandoned tin cans, “not very valuable, yet not worthless,” and speculated that they might have been left if Franklin departed Beechey in a hurry—as a result, for example, of the ice breaking up unexpectedly.

The main question, of course, was where had Franklin gone? Entranced by speculations of the Open Polar Sea, Kane imagined that in the early summer of 1846, Franklin had gazed out anxiously, waiting for the ice to open. The first lead or opening to appear in the ice would, he thought, almost certainly run northwest along the coast of Devon Island. Would Franklin wait until Lancaster Sound opened to the south, and then sail back to try the upper reaches of Baffin Bay? “Or would he press to the north,” Kane asked, “through the open lead that lay before him?”

Anybody who knew Franklin’s character, determination and purpose, Kane insisted, would find the question easy to answer. “We, the searchers, were ourselves tempted, by the insidious openings to the north in Wellington Channel, to push on in the hope that some lucky chance might point us to an outlet beyond. Might not the same temptation have had its influence for Sir John Franklin? A careful and daring navigator, such as he was, would not wait for the lead to close.”

It did not occur, even to the imaginative Kane, that before making camp on Beechey Island, Franklin might already have investigated Wellington Channel. And that, with heavy ice to the west, he had only one way to go: south.