16.

John Rae Mounts a Tour de Force

In May 1850, as the thirty-year-old American doctor Elisha Kent Kane sailed north out of New York City, Scottish doctor John Rae, seven years older, was canoeing down the Mackenzie River to the Arctic coast. Recently appointed head of district for the Hudson’s Bay Company, Rae went to supervise the gathering of furs collected during the winter. As part of an annual cycle, traders stationed on the Mackenzie had to transport furs upriver in June to catch the HBC ships sailing for England from York Factory. Beyond Fort Simpson, to reduce blockages and traffic jams, those in charge would split the “Mackenzie Brigade” into two, giving half the boats a head start of several days.

On June 16, 1850, when off the coast of Greenland Kane was sailing amidst astonishing icebergs, Rae sent his second-in-command back upriver with four well-laden boats. Four days later, he followed with five more boats, portaging and tracking. For nine days, from two o’clock in the morning until eight or nine at night, Rae led his men up the Mackenzie, halting briefly for breakfast, eating dinner only after landing at night, and snacking on pemmican to keep going.

During the previous cold, dark winter, while based at Fort Simpson, Rae had written George Simpson requesting a leave of absence. After his recent hard work in searching for John Franklin, he anticipated that this would be granted. From York Factory, he intended to keep right on travelling, first to New York City and then to his beloved Orkney.

Just over two years earlier, on April 10, 1848, Rae and John Richardson had reached New York City from Liverpool. They had travelled north to Montreal by steamship, and spent three days with Sir George Simpson at his stone mansion in nearby Lachine. Anxious to begin their search, they left separately. Richardson travelled west in the steamer British Empire, and Rae took passage in the Canada, supervising eleven Iroquois and French-Canadian voyageurs who would form the backbone of a canoeing crew of sixteen.

In early May, reunited, Rae and Richardson paddled northwest out of Sault Ste. Marie, hugging the coast of Lake Superior, the so-called King of Lakes, which Richardson rightly described as occupying nearly as much space as the whole of England. The two Scots travelled in separate canoes, each with eight voyageurs, and followed the usual fur-trade route.

At Cumberland House, having travelled 2,237 kilometres from Sault Ste. Marie in forty-one days, Rae caught up with Chief Trader John Bell and the twenty British servicemen who, having arrived from York Factory, would accompany them to the Arctic. On June 13, 1848, after interviewing these men, Rae wrote to George Simpson expressing misgivings. None of the miners, sappers and sailors were accustomed to portaging, or to travelling in canoes and small boats. None were hunters. Neither the four boats nor the British servicemen were suited to the work ahead. The only positive development, Rae wrote, was that Albert One-Eye, a young Inuk interpreter, had joined the expedition.

Rae had met the youth in 1842 at Moose Factory. Since Albert had full use of both eyes, probably he was the son of a man who had lost an eye. He had been born around 1824 on the east coast of James Bay, in the so-called “Eastmain” of HBC territory. When he was eighteen, a visiting chief trader thought that Albert showed promise. He brought him across Hudson Bay to Moose Factory, the largest post in the south. John Rae was already there when Albert signed on to work for seven years as an apprentice labourer.

Within the year, however, he was seconded to work as an interpreter at Fort George, some distance north of Eastmain. He was still there early in 1848 when Rae had thought to request his services. From Fort George, HBC trader John Spencer wrote that he was “exceedingly sorry to part with him,” adding that Albert was “a nice steady lad, and a favourite with his tribe.” On June 13, from Cumberland House, Rae wrote to Simpson that he and Richardson were bringing no hunters to the Arctic coast. They would depend on Rae’s own hunting, and on “the exertions of our Esquimaux interpreter . . . a fine active lad” who would “no doubt prove to be a good deer hunter.”

While John Richardson was the nominal leader of the search expedition, John Rae, infinitely more capable in rough country, took charge. He led the party north through Great Slave Lake and, in August 1848, down the Mackenzie River. Albert One-Eye had no difficulty communicating with the Inuit of the Mackenzie Delta, as Richardson later attested. One local man, asked whether any white men were living on a given island, said yes. Richardson had visited that island the previous day and knew otherwise. He told Albert to tell the man he was lying. “He received this retort with a smile,” Richardson wrote, “and without the slightest discomposure, but did not repeat his assertion.” As historian Kenn Harper has noted, Albert would appear to have conveyed Richardson’s assertion less confrontationally than the explorer himself.

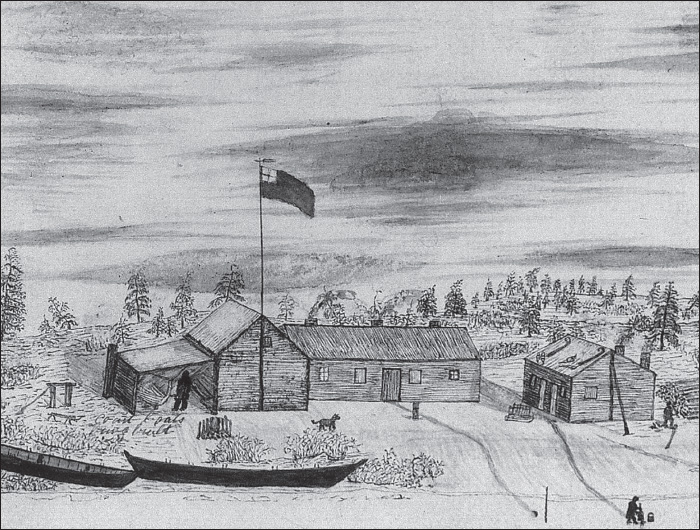

Fort Confidence, Winter View, 1850–51. John Rae created this pen-and-ink drawing.

From the mouth of the Mackenzie, Rae followed the coast eastward, retracing the route Richardson had followed two decades before. With winter coming on, and having found no sign of Franklin, he led the way up the Coppermine River and then to Great Slave Lake. He and Richardson spent the winter at Fort Confidence, which Dease and Simpson had built a decade before. They erected a small observatory and took meteorological readings sixteen or seventeen times a day. Decades later, weather historian Tim Ball would note that “no one kept more precise records than John Rae.”

During the winter of 1848–49, Richardson turned sixty-one. He could see that, given Rae’s abilities, he himself had become superfluous. In May 1849, he started the long journey home to England. Before he left, Rae elicited written instructions to seek Franklin along the shores of Wollaston Land and Victoria Land, and to abandon the quest at the end of the year. From Fort Confidence, Rae informed George Simpson that he would descend the Coppermine River, and then try to cross Dolphin and Union Strait to Victoria Island. The crew would include Albert, whom he described as “a very fine lad” and “fit for any of the duties of a labourer.”

From Fort Confidence, Rae set out on June 7. On reaching the coast in early July, he found Coronation Gulf still clogged with ice. With half a dozen men, he pushed on to Cape Krusenstern, bent on crossing the fast-flowing Dolphin and Union Strait to Wollaston Land. Ice prevented any such crossing. Finally, on August 19, spying more open water than before, Rae pushed out into the swirling floes.

The men reached open water and rowed on through a soupy fog. They covered twelve kilometres, but then came up against a driving stream of rolling ice floes. With visibility approaching zero, Rae gave the order to turn back. After struggling for three hours, the men emerged from the fog and ran up onto an icy barricade. They hauled the boat for almost a kilometre, attaining land several hundred metres south of their original campsite. Rae hoped to try again, and waited two more days, but a northern gale blew up and jammed “our cold and persevering opponent in large heaps along the shore.”

Finally, amidst howling winds and driving rain, Rae acknowledged that he had run out of time. Even if John Franklin waited just across the channel, nobody was going to reach him on this occasion. Rae started leading the way up the Coppermine River. Then, on August 24, after getting past Bloody Falls, tragedy struck. The men had successfully manoeuvred their boat up the most treacherous part of the rapids and had reached an area where the current was strong but the river smooth.

Rae judged it safe to take a loaded boat up the river, with some of the men on shore hauling it along with a rope. “When halfway up some unaccountable panic seized the steersman,” wrote Rae, and “he called on the trackers to slack the line, which was no sooner done sufficiently far, than he and the bowsman sprung on shore, and permitted the boat to sheer out into midstream [where] the line snapped, and the boat driving broadside to the current was soon upset.”

John Rae and Albert One-Eye ran along the riverbank, hoping that the boat would get caught in an eddy. The boat passed close to where Albert stood waiting, and he managed to hook it by the keel with an oar. Rae ran to help him. He snatched a pole from the water and jammed it into a broken plank. He called to Albert to hold on with him. Either Albert didn’t hear him or thought he had a better idea. He sprang onto the capsized boat just before the current swept it towards the head of a little bay. Rae thought Albert was safe there, but in seconds he saw the boat come out of the protection of the bay, driven by the current. It began sliding beneath the surface. Albert tried to leap from the boat onto the rocks. Rae wrote later that the young man slipped and tumbled into the water, “nor did he rise again to the surface.”

For Albert’s death, Rae never forgave the steersman, whom he described as “a notorious thief and equally noted for falsehood.” He had hoped that, once this expedition was done, he would be able to keep Albert with him when he took charge of the Mackenzie River District. Rae had told Simpson that “he would be useful in the event of it becoming desirable to have any negotiations with the Esquimaux at the mouth of the Mackenzie,” and he hoped “to make him in every way a most useful man to the Company.”

At Fort Confidence, Rae mourned the loss of Albert One-Eye. “This melancholy accident has distressed me more than I can well express,” he wrote. “Albert was liked by everyone, for his good temper, lively disposition and great activity in doing anything that was required of him. I had become much attached to the poor fellow.”

Now, on June 25, 1850, one day shy of Great Slave Lake, and while dreaming of returning home to his beloved Orkney, Rae encountered two native canoeists carrying an “extraordinary express.” He went ashore to accept delivery, then sat on the banks of the broad, fast-flowing river to read three communications. The first came from George Simpson at Lachine. Searchers had found no trace of John Franklin. England grew increasingly alarmed. Simpson wanted Rae to renew his search immediately, and to travel farther north than ever before. Reeling, Rae turned to the other two letters. From London, Lady Franklin wrote in a friendly, respectful and indeed flattering manner: “[My anticipations were not] so extravagant as other people’s, for it has been the custom of people to throw upon you everything that others failed to accomplish—‘oh Rae’s in that quarter, Rae will do that’—as if you and your single boat could explore hundreds of miles NSE & West and as if no obstacles of any kind could interfere . . . Myself, I think that your quarter is by far the most promising of any, for it is the quarter to which my husband was most distinctly . . . directed to proceed, and where I have no doubt he directed his most strenuous efforts.”

Also from London, Sir Francis Beaufort, the Admiralty’s chief hydrographer—England’s official mapmaker—contributed a final letter: “I cannot let the mail go without telling you how intensely fixed all eyes are upon you . . . [and] upon what is yet in your power, and in yours alone, to do next season . . . Let me then, my dear Doctor, add my voice to the moans of the wives and children of the two unfortunate ships, and to the humane and energetic suggestions of your heart, and implore you to save neither money nor labour in fulfilling your holy mission. Two ships will sail in ten days for Bering Strait—others in spring for Baffin Bay. The Americans are preparing an expedition but to you I look for the solution of our melancholy suspense.”

Having read the letters through, Rae walked alone along the banks of the Mackenzie. He felt as low as he had ever felt in his life. On his last expedition, he had failed not only in his main objective, finding Franklin, but even in his secondary one of reaching Wollaston Land and perhaps discovering the final link in the Northwest Passage. About Franklin, missing now for five years, nobody could hope to discover good news. Rae had been dreaming not of returning to Arctic searching, but of travelling to Orkney and then London to seek a wife. Instead of strolling around Hyde Park with a pretty girl on his arm, he would soon be battling blizzards in the fierce, unforgiving North. He stood looking over the Mackenzie River, swiping at the mosquitoes that swarmed around his head. Why, oh why, hadn’t Franklin stayed home?

On the Mackenzie River, while discharging his responsibilities as chief factor, John Rae organized a two-part expedition to resume the search for Franklin—a tour de force. Come autumn, he would return north to Fort Confidence with fourteen men (and a few country wives). During the ensuing winter, he would design and build two boats. Next spring, having secured enough food through hunting and fishing, he would set out. Before the ice thawed, he would lead a few men to the Arctic coast. On snowshoes, he would cross the Dolphin and Union Strait and explore the shores of Victoria Land. He would recross that strait before spring thaw and travel to a temporary provision station on the Kendall River near the coast. There he would meet a contingent of his men, who would have dragged the two boats to that location. Then, with a larger party, he would descend the Coppermine River and, as the ice broke up, sail the boats into Coronation Gulf and beyond.

Having envisaged this two-part search, John Rae set about making it real. At Fort Confidence during the ensuing winter, Rae taught John Beads and Peter Linklater—two men of Orcadian background born in Rupert’s Land—how to build igloos. These two would accompany him on the first part of the expedition. Rae also gave Hector Mackenzie, his popular, fiddle-playing second-in-command, also from Rupert’s Land, detailed instructions covering every contingency. He advised him what to do, for example, if Rae himself failed to return, if he sent word of some important finding or if letters arrived announcing that Franklin had been found.

The party would carry no useless weight. While naval officers sledding in the Arctic would haul bedding weighing almost twenty-five pounds per man, Rae had reduced this by limiting himself and his companions to one blanket, one deerskin robe and two hairy deer-skins. Writing to George Simpson, he had described this as “rather luxurious, being 22 lbs. weight for all, but we can easily lighten it if required.”

When travelling, Rae wore Inuit-style clothing: a fur cap, large leather mitts with fur around the wrist, and moccasins made of smoked moose skin, large enough to accommodate two or three blanket socks and with thongs of skin stretched across the soles to prevent slipping. He also wore a light cloth coat with its hood and sleeves lined with leather, a cloth vest and thick moose skin trousers. He carried “a spare woolen shirt or two and a coat made of the thinnest fawn skin with the fur on, weighing not more than four or five pounds, to put on in the snow hut, or when taking observations.” His personal effects consisted of a pocket comb, a toothbrush, a towel and a bit of coarse yellow soap.

With preparations complete, Rae set out on part one of his expedition. He donned his snowshoes and, on April 25, 1851, led four men and four sledges east out of Fort Confidence. Dogs hauled three of the sledges, harnessed not in rows, as was British naval practice, but in an Inuit-style fan-out. Two men hauled the fourth sledge. For the snowshoe journey, Rae carried enough pemmican and flour to last thirty-five days and enough grease to serve as cooking fuel at a rate of one pound per day. Unlike government sledging parties, his would not stop for lunch but only for a moment to take what the Hudson’s Bay men called “a pipe,” eating a mouthful or two of pemmican before resuming the trek.

The weather turned ugly on April 27 as Rae arrived at the Kendall River station. After huddling in an igloo through two days of stormy weather, Rae led them with his men north. The fatigue party travelled to within sixteen kilometres of the Arctic coast, doing most of the heavy hauling, and turned back on May 2. Rae pressed on with Beads and Linklater, both of whom had been born in Rupert’s Land and were in their early twenties: fit men and ideal travelling companions.

On reaching the Arctic coast at Richardson Bay eight kilometres west of the mouth of the Coppermine River, Rae found the ice ahead free of hummocks and pressure ridges and not unfavourable for travelling. In the afternoon, with the sun high in the sky, the glare off the ice and snow threatened the men with snow blindness, whose victims feel as if sand has lodged in their eyes. To avoid this, Rae decided to rest during the day and travel by night, when visibility would resemble that of twilight at the lower latitudes.

John Rae identified with and learned from the native peoples, both First Nations and Inuit. This watercolour portrait, Dr. John Rae, Arctic Explorer (1862) by William Armstrong, comes from the Glenbow Museum in Calgary.

Two hours before midnight, he donned snowshoes and set out across Coronation Gulf towards Wollaston Peninsula on Victoria Island. In order to examine bays, rivers and inlets while his men drove the dogs straight ahead, Rae hauled a small sledge piled with bedding, instruments, pemmican, a musket and tools for building a snow hut. After slogging along the coast, he touched land at Point Lockyer and then crossed Dolphin and Union Strait by way of Douglas Island, where he cached provisions for the return journey.

Four days out, near Cape Lady Franklin, Rae reached Wollaston Land, believed at the time to be separate from Victoria Island. Searching for the lost ships of the Franklin expedition and for a non-existent strait between Wollaston and Victoria, Rae travelled east along the coast. At one point, between observations for time and latitude, Rae shot ten hares: “These fine animals were very large and tame, and several more might have been killed, also a number of partridges, had it been requisite to waste time or ammunition in following them.”

When the temperature plummeted to thirty degrees below zero Celsius, the men—one of them badly frostbitten in the face—retreated with satisfaction to their latest igloo. On May 10, Rae ventured beyond where Dease and Simpson had reached in 1839, having passed this point from the east without encountering any north-south strait. From here, he would soon resume the search by boat. Now he turned around to retrace his steps, bent on searching to the west of his landing spot.

That night, a snowstorm reduced visibility to sixty feet. Fortunately, the snowshoers had the wind at their backs. Rae found their previous track and so didn’t need repeatedly to take bearings: “After a very cold but smart walk of rather more than seven hours duration, we were very glad to find ourselves snug under cover of our old quarters, our clothes being penetrated in every direction with the finely powdered snow.”

The storm that raged through the next night made travel impossible, but in the morning, accompanied by the panting of dogs, the creaking of sledges and the gentle whump whump whump of snowshoes, Rae again headed west dragging his sledge, which weighed over thirty-five pounds. Battling rough ice and blowing snow, following the coast as it swung north, Rae came upon thirteen Inuit lodges. He chatted amicably with the inhabitants. Timid at first, they soon gained enough confidence to sell him seal meat for the dogs and boots, shoes and sealskins for the men. These Inuit, living on the west coast of Wollaston Peninsula, had seen neither white men nor sailing ships.

By May 23, with spring thaw threatening to trap the boatless party on the wrong side of Dolphin and Union Strait, Rae realized he must soon turn back. Resting in the igloo as night came on, scribbling notes by candlelight, the explorer decided to make one last sortie northward. He would travel light, bringing only Peter Linklater, the faster of the two young men, and leaving the dogs and John Beads to rest in the camp before the long return journey.

After midnight, when finally the sun dipped below the horizon, Rae shook Linklater awake. He boiled water and sipped a cup of tea, then donned his snowshoes and led the way north along the unexplored coast of Wollaston Land. Having left camp with only a compass, a sextant and a musket for protection against wolves and bears, the two men travelled fast. They walked for six hours, stopping to rest only once, briefly, at the younger man’s request. At last, as the rising sun heralded the dawn, Rae rounded Cape Baring. Linklater had fallen some distance behind but the explorer forged on ahead, excited now, climbing a promontory from which, in the distance, he could see a high cape.

This impressive landmark he named Cape Back, after George Back, who in 1821, by finding a band of Yellowknife-Dene, had saved Franklin and Richardson from starving to death at Fort Enterprise. Between that cape and the promontory on which he stood, Rae could see a large body of water (Prince Albert Sound), and wondered whether it might prove to be an east–west strait. Just ten days before, on May 14, 1851, a sledge party from Robert McClure’s icebound Investigator had reached the other side of the sound, sixty-four kilometres north—though of course Rae could not know that. He yearned to keep walking, but knew that he had run out of time.

On May 24 Rae began to retrace his steps. He verified readings, retrieved caches and encountered a few friendly Inuit hunters. None of them had seen or heard of any Europeans. Six days after turning back, and having retrieved John Beads, Rae and his two men recrossed Dolphin and Union Strait to a high rocky point north of Cape Krusenstern. By June 4, when the trio reached Richardson Bay, a layer of water on the ice confirmed that they had concluded their snowshoe and dogsled journey just in time.

Rae and his men reached the Kendall River station by trekking for five days from the coast, “during some of which we were fourteen hours on foot and continually wading through ice cold water or wet snow which was too deep to allow our Esquimaux boots to be of any use.” At one point Linklater slipped and lost all the cooking utensils, plates, pans and spoons. For the last two days, the men ate from large, flat stones. They survived on geese, partridges and lemming, these last proving especially tasty when roasted over the fire or between two stones.

In his official report, Rae praised his two travelling companions. He calculated that, starting from the Kendall River, he had covered 824.5 nautical miles, or 1,516 kilometres, and he speculated, in private correspondence, that this was “perhaps the longest [journey] ever made on the arctic coast over ice.”

Now came part two of the landmark expedition. On June 13, 1851, Hector Mackenzie joined Rae at Kendall River, arriving as planned from Fort Confidence with eight men and two boats. Two days later, with Mackenzie and ten men, Rae proceeded down the Kendall towards the Coppermine. Ice forced the party to wait for almost a week at the confluence. After further delays, by portaging around the impossible stretches and running the merely difficult ones, the party made it to Bloody Falls. There, by placing a net in an eddy below the falls, they caught forty salmon in fifteen minutes.

At the mouth of the Coppermine, Rae set up camp and waited for the pack ice to melt farther out on Coronation Gulf. Finally, early in July, a breeze opened a narrow channel eastward. Seizing the moment, Rae sailed thirty-five kilometres by nightfall, when ice made further progress impossible. From that point on, he proceeded along the coast by taking advantage of any open water. Progress was slow and difficult. In many places, the ice lay against the rocks, forcing the men to make portages. This work, though arduous, had fortunately become routine for the steadily improving crew.

The weather remained changeable. On the morning of July 16, as Rae and his men rounded Cape Barrow, they found themselves sailing into a torrent of rain. After they put ashore for breakfast, the weather cleared and Rae climbed a promontory. The highest rocks afforded him a discouraging view north and east across Dease Strait. As far as the eye could see, the strait lay covered by an unbroken sheet of ice—ice so thick and strong that hundreds of seals cavorted along its edges.

Rae reboarded the boats and carried on, making slow progress by following crooked lines of water through the ice. Six days beyond Cape Barrow, a stiff southeasterly breeze opened a channel towards Cape Flinders at the western point of Kent Peninsula. Nearing that cape, which Franklin had named during his first disastrous expedition, Rae spotted three Inuit hunters and put ashore. Half a dozen other Inuit watched from a nearby island.

The explorer approached the hunters, noting that they looked thinner and less well-fed than the Arctic native people he had met around Repulse Bay. The men at first appeared alarmed and fearful, and again Rae regretted the loss of Albert One-Eye. He offered the strangers trinkets, a gesture that gained their confidence. These men had never before communicated with Europeans. Using gestures, sign language and Inuktitut words and phrases that he had picked up, Rae questioned the men for half an hour. They had lived here all their lives, but no, they had seen no great ships. Nor had they seen any foreigners. Rae was the first.

Disappointed but not surprised, Rae resumed his voyage eastward. He passed Point Turnagain, where in 1821—and far too late in the season—Franklin had finally turned around and begun his desperate overland retreat. Rae reached Cape Alexander, at the eastern end of Kent Peninsula, on July 24, two days earlier than Dease and Simpson had done in 1839. From here, where Dease Strait was narrowest, Rae proposed to cross to the southern coast of Victoria Land. Soon afterwards he wrote: “Had geographical discovery been the object of the expedition, I would have followed the coast eastward to Simpson Strait and then have crossed over towards Cape Franklin [on King William Island]. This course, however, would have been a deviation from the route I had marked out for myself, and would have exposed me to the charge of having lost sight of the duty committed to me.”

Ironically, indeed tragically, had Rae carried on farther east, he would probably have discovered the fate of the Franklin expedition. He might have spotted the Erebus or the Terror, one or both of which were probably still afloat, and rescued some final survivors. If he did not see either one of those vessels, then almost certainly, on the southwest coast of King William Island, he would have found frozen corpses—some under boats, others in tents, still others face down in the snow. And he might well have found journals, diaries and last letters.

But on July 27, 1851, as the winter ice began breaking up, the dutiful Rae beat north across Dease Strait to Victoria Land. He put into Cambridge Bay and, when a storm blew up, stayed for two days. Early in August, the men reached Cape Colborne. From that point east, Rae began delineating coastline that had never been charted. After travelling more than 150 kilometres without stopping except to cook, Rae reached an insurmountable ice barrier.

The shore lay barren of vegetation and even of driftwood. A tract of light grey limestone had been forced up in immense blocks close to the shore by the pressure of ice. From the north came yet another gale, with heavy squalls and showers of sleet and snow. Finally the wind fell and a lane opened up along the coast, revealing reefs. Rounding these, Rae emerged into open water, set close-reefed sails and beat onwards through an ugly, chopping sea. The slightly built boats strained and heaved as pounding waves washed over them, but eventually Rae entered a snug cove and secured them.

On August 5, in heavy weather, Rae passed high limestone cliffs rutted with deep snow. A thick, cold fog came on, encrusting the boats with ice, so he landed and broke out tents. As evening came on, the men forced their way forward for another five kilometres, pulling and poling against ever-thicker ice. Finally, just north of Albert Edward Bay, the boats ground to a halt.

For the next two days, a relentless northeast wind kept the ice close to the shore and showed no signs of changing. Rae decided to press ahead overland. What if Franklin had reached the coast directly ahead? Or what if the waterway Rae had seen on the west coast of Wollaston Land was in fact a strait that emerged just ahead, providing a final link in the Passage?

Just before noon on August 12, with three men, his trusty musket and enough food to last four days, Rae began hiking north. “Hoping to avoid the sharp and ragged limestone debris with which the coast was lined,” he wrote, “we at first kept some miles inland, without however gaining much advantage, as the country was intersected with lakes, to get round which we had to make long detours. Nor was the ground much more favourable for travelling than that nearer the beach; in fact, it was as bad as it well could be, in proof of which I may mention that, in two hours, a pair of new moccasins, with thick undressed buffalo skin soles, and stout duffle socks were completely worn out, and before the day’s journey was half done every step I took was marked with blood.”

When Rae got back to the boats, he deposited a note in a cairn. It summarized his expedition and mentioned that he had explored the coast to thirty-five miles (fifty-six kilometres) north from this point. Two years later, in May of 1853, a sledging party from HMS Enterprise, wintering in Cambridge Bay under Captain Richard Collinson, would find it.

Early on August 15, 1851, with a fierce wind blowing from the north-northeast and the boats in danger if the wind shifted to the east, Rae sailed back a few kilometres to a safer harbour. There he waited for any favourable change in the wind and ice that would allow him to use the shelter of Admiralty Island (which he had named the previous week) to cross Victoria Strait to what he called “Point Franklin” on King William Land—by which he meant a promontory between Victory Point and Cape Crozier.

If Rae had managed to cross Victoria Strait to this point, again he would have discovered the fate of Franklin: this is the region in which many of Franklin’s men died while struggling south along the coast of King William Island. It was not to be, however. Late that morning, Rae sailed out into the strait, but the breeze increased to a gale and shifted to the east. Facing a great accumulation of ice, Rae sought shelter in the lee of a point. The following morning, when the wind subsided, he tried once again to push across to Admiralty Island, but the ice was worse than ever.

Four days later and some kilometres farther south, Rae made a third attempt to force a passage eastward to King William Land. But after eight kilometres, he reached a wall of close-packed ice and that left him no choice but to turn back. Rae could not know it, but the conditions he encountered recur even today, because pack ice breaking off from the polar cap travels south down the broad McClintock Channel and jams into the narrower Victoria Strait. Ironically, the Canadian expedition that in 2014 located the Erebus did so only because heavy ice prevented its ships from searching this area.

In 1851, unable to reach King William Island, Rae proceeded southwest. On August 21, while creeping along the shore of what he called Parker Bay, Rae chanced upon a length of pinewood. He examined it with growing excitement. This was not driftwood but a piece of man-made pole. Almost six feet long, three and one-half inches in diameter, and round except for the bottom twelve inches, which were square, it appeared to be the butt end of a small flagstaff. It was stamped on one side with an indecipherable marking, and a bit of white line had been tacked to the pole near the bottom, forming a loop for signal halyards. Both the white line and the copper tacks bore the marks of the British government: a red worsted thread, the “rogue’s yarn,” ran through the white line, and a broad arrow was stamped on the underside of the head of the copper tacks.

Rae was still carefully describing this pole in his journal and had not travelled more than a few hundred metres when the two boats came upon another stick of wood lying in the water, touching the beach. This one was a piece of oak almost four feet long and three inches in diameter, with a hole in the upper end. This post or stanchion had been formed in a wring lathe. The bottom was square, and Rae deduced from a broad rust mark that it had been fitted into an iron clasp.

Anticipating a debate over the sources of these pieces of wood, Rae offered his analysis in his official report, and so became the first explorer to identify Victoria Land as an island. Citing the flood tide from the north, he argued that a wide channel must separate Victoria Land from North Somerset Island and that these pieces of wood had been swept down this channel along with the immense quantities of creeping ice. In his rough notes, though not in his report, Rae wrote of the two poles, “They may be portions of one of Sir John Franklin’s ships. God grant that the crews are safe.”

Like the vast majority of naval experts, Rae believed that the lost expedition would be found far to the north. His discovery of the two pieces of wood did not change his opinion. He correctly guessed the direction from which the broken pieces had come, but overestimated the distance they had travelled.

With these broken pieces of wood, John Rae became the first explorer to discover relics from one of the Franklin ships after it had got trapped in the ice. In his official report, he confined himself to description. After carefully stowing away the wood, the copper tacks and the line, Rae turned his attention to the wind and the waves.

From Parker Bay, Rae made excellent time sailing west. On August 29, he crossed Coronation Gulf and found the Coppermine River raging. When the water did not fall for two days, Rae proclaimed confidence in the skill of his men and started up the river. The ledges of rock that ran along the base of the cliffs lay hidden beneath the driving current, so tracking meant walking along the top of the cliffs. The men’s strongest cord snapped four times, and so they entered the pounding river to shove the boat over the rocks. After five days of furious work, the party made camp at the Kendall River, the worst of the trek behind them.

A few days later, on September 10, 1851, Rae and his men regained Fort Confidence. Finding everything in order and more than three thousand pounds of dried provisions in store, Rae instructed Hector Mackenzie to close the post and pay the men, specifying bonuses and gratuities. Later, his superiors would complain of his generosity.

During his snowshoe sortie, Rae had trekked 1,740 kilometres, one of the longest such expeditions ever made over Arctic ice. He had immediately followed this with a second stunning achievement. His summer voyage east and then north along Victoria Island, during which he sailed 2,235 kilometres while charting 1,015 kilometres of unexplored coastline, stands in comparison with the Dease and Simpson voyage of 1838–39, which set an Arctic standard for small-boat travel. In addition to these physical and geographical accomplishments, Rae had discovered the first relics from the Franklin expedition.

The day after he arrived at Fort Confidence, having completed one of the most remarkable Arctic expeditions of all time, John Rae set out southward to enjoy his hard-earned leave of absence. He was bound for Orkney and nothing was going to stop him.