2.

Catastrophe Engulfs Jens Munk

Despite what happened to Henry Hudson, explorers continued to seek an eastern entrance to the Northwest Passage through Hudson Bay. In 1619, soon after Robert Bylot and Thomas Button searched the Bay and found no way through, the Danish-Norwegian explorer Jens Munk, unconvinced, sailed into the Bay with sixty-four men in two ships. The Unicorn, a frigate, carried forty-eight men, and the sloop Lamprey, sixteen.

A veteran seaman at thirty-nine, Munk had been sailing since boyhood, and had served with distinction during a war against Sweden. More recently, as a result of a failed High Arctic whaling initiative, he had lost a fortune and no small amount of prestige. Munk sought the Northwest Passage as a way of restoring his damaged reputation. In this he anticipated John Franklin who, with much the same motive, would embark more than two centuries later. As we shall see, the catastrophes that engulfed the two expeditions would resonate in other ways.

Late in the summer of 1619, having sailed from Copenhagen and probed Frobisher Bay on Baffin Island, Munk beat his way through the treacherous Hudson Strait, which he called “Fretum Christian” after his sovereign, Christian IV. On the north shore of the strait, while hunting caribou on July 18, he had an ultimately friendly encounter with Inuit hunters.

In The Journal of Jens Munk, 1619–1620, translated into modern English by Walter Kenyon, we read that, having spotted the hunters from the Unicorn, Munk jumped into a boat with a few sailors. “When they saw that I intended to land,” he writes, “they hid their weapons and other implements behind some rocks and just stood waiting.” After landing, though the Inuit tried to stop him, Munk strode over, picked up the weapons, and examined them. “While I was looking them over,” he notes, “the natives led me to believe that they would rather lose all their clothing and be forced to go naked than lose their weapons. Pointing to their mouths, they indicated that they used the weapons to procure their food.” When Munk laid the weapons aside, “they clapped their hands, looked up to heaven, and seemed overjoyed.”

Munk presented the hunters with knives and other metal goods. He gave a looking-glass to one man, who did not know what it was. “When I took it from him and held it in front of his face so that he could see himself, he grabbed the glass and hid it under his clothing.” The hunters gave Munk numerous presents, including various kinds of birds and seal meat. “All the natives embraced one of my men,” he added, “who had a swarthy complexion and black hair—they thought, no doubt, that he was one of their countrymen.”

A few days later, returning to this harbour, Munk hoped to see more of the Inuit but encountered none. In typical European style, he erected a marker bearing “the arms of His Royal Majesty King Christian IV” and, because of the excellent hunting, named the harbour Reindeer Sound. Near the Inuit fishing nets, he left a few knives and trinkets. And then he resumed his difficult voyage into unknown waters, drifting “wherever the wind and the ice might carry us, with no open water visible anywhere.”

With winter coming on, Munk managed to cross Hudson Bay, which he called “Novum Mare Christian.” On September 7, he entered the estuary of the Churchill River “with great difficulty, because there were high winds, with snow, hail, and fog.” Here, in “Jens Muncke’s Bay,” he sheltered his ships and settled in for winter. Some of the men had fallen ill, so he had them taken ashore. He built a fire to comfort the sick, but the party ended up huddling in tents through a terrible, two-day snowstorm.

Now came a moment worth noting. “Early the next morning,” Munk writes, “a large white bear came down to the water’s edge, where it started to eat a beluga fish that I had caught the day before. I shot the bear and gave the meat to the crew with orders that it was to be just slightly boiled, then kept in vinegar overnight. I even had two or three pieces of the flesh roasted for the cabin. It was of good taste and quite agreeable.”

Munk sent men to investigate the surrounding woods. On September 19, after consulting with his officers, he sailed the Unicorn and the sloop upriver as far as possible. By October 1, he had both vessels secured and well protected. He had all the men take their meals on the Unicorn so as not to keep two galleys going at once. Soon he was making scientific observations and recording opinions on bird migrations and the origins of icebergs. Having always intended to live off the land, Munk encouraged his men to hunt the flocks of ptarmigan and partridge.

On November 21, Munk writes, “We buried a sailor who had been ill for a long time.” This would prove a harbinger of things to come. On December 12, one of the two surgeons died: “We had to keep his body on the ship for two days because the frost was so severe that no one could get ashore to bury him.” On Christmas Eve, as yet unconcerned, Munk gave the men “some wine and strong beer, which they had to boil as it was frozen.” Over the next few days, the men played games to amuse themselves. “At the time,” Munk writes, “the crew was in good health and brimming with excitement.”

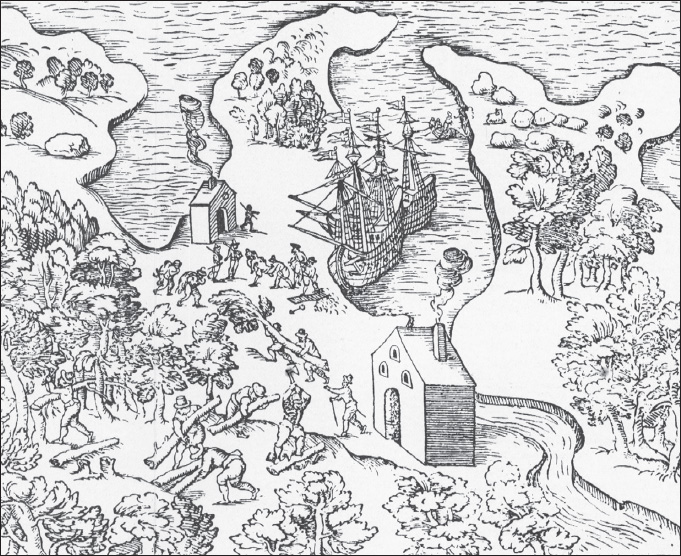

This stylized woodcut map of the estuary of the Churchill River, originally published by the Hakluyt Society in 1897, depicts the Jens Munk expedition soon after it arrived in 1619 to spend the winter. Here we see Munk’s two ships on the west side of the harbour. In this bucolic representation, complete with two well-built houses, a few men are logging, two are returning from a hunt with dead caribou slung over their shoulders and several are preparing to bury one of their comrades—a dark omen of what is to come. According to the Historical Atlas of Manitoba, this is the first large-scale map of a Manitoba locale. In 1783, after a French fleet destroyed the nearby Prince of Wales Fort, Samuel Hearne built Fort Churchill at this spot.

The trouble began in earnest on January 10, when the priest and the remaining surgeon “took to their beds after having been ill for some time. That same day my head cook perished. And then a violent illness spread among the men, growing worse each day. It was a peculiar malady, in which the sick men were usually attacked by dysentery about three weeks before they died.”

The healthy men, dwindling in numbers, continued to hunt and provide for the rest. But by January 21, thirteen men were down with the sickness, among them the sole remaining surgeon, “who was mortally ill by then.” Munk pleaded with that man “if there was not some medicine in his chest that would cure the men, or at least comfort them. He replied that he had already used every medicine he had with him, and that without God’s assistance he was helpless.”

Two days later, one of the mates died after a five-month illness. That same day, “the priest sat up in his berth and preached a sermon, the last one he was ever to deliver in this world.” Munk pleaded with the dying surgeon for advice, but received the same answer as before. By February 16, Munk writes, only seven men “were healthy enough to fetch wood and water and do whatever else had to be done on board.” The following day, the death count reached twenty.

In his journal, Munk records death after death. The cold grew so severe that nobody could go ashore to fetch food or water. A kettle burst when the water inside turned to ice. Munk and his men had never experienced such a winter. Occasionally, someone would go ashore and shoot a few ptarmigan, providing a welcome addition to the larder. Some of the men “could not eat the meat,” Munk writes, “because their mouths were so swollen and inflamed with scurvy, but they drank the broth that was distributed amongst them.”

Late March brought better weather, but “most of the crew were so sick that they were both melancholy to listen to and miserable to behold.” By now the illness was raging so violently “that most of those who were still alive were too sick even to bury the dead.” Munk examined the contents of the surgeon’s chest but could make no sense of what he found: “I would also stake my life on the opinion that even the surgeon did not know how those medicines were to be used, for all the labels were written in Latin, and whenever he wished to read one, he had to call the priest to translate it for him.”

Munk writes that his “greatest sorrow and misery” started as March ended, “and soon I was like a wild and lonely bird. I was obliged to prepare and serve drink to the sick men myself, and to give them anything else I thought might nourish or comfort them.” On April 3 the weather turned so bitterly cold that nobody could get out of bed: “nor did I have any men left to command, for they were all lying under the hand of God.” By now, so few were healthy “that we could scarcely muster a burial party.”

By Good Friday, besides Munk himself, only four men “were strong enough to sit up in their berths to hear the homily” marking the occasion. By this time, Munk writes, “I too was quite miserable and felt abandoned by the entire world, as you may imagine.” Later in April, the weather improved enough that some men could crawl out of their berths and warm themselves in the sun: “But they were so weak that many of them fainted, and we found it almost impossible to get them back into bed.”

Men continued to die, sometimes two or three a day. The living were now “so weak that we could no longer carry the dead bodies to their graves but had to drag them on the small sled that was used for hauling wood.” By May 10, eleven men remained alive, all of them sick, including Munk. When two more men died, Munk writes, “only God can know the torments we suffered before we got them to their graves. Those were the last bodies that we buried.” Those who died now remained unburied on the ship.

By late May, seven men lived on. Munk writes: “We lay there day after day looking mournfully at each other, hoping that the snow would melt and that the ice would drift away. The illness that had fallen upon us was rare and extraordinary, with most peculiar symptoms. The limbs and joints were miserably drawn together, and there were great pains in the loins as if a thousand knives had been thrust there. At the same time the body was discoloured as when someone has a black eye, and all the limbs were powerless. The mouth, too, was in miserable condition, as all the teeth were loose, so that it was impossible to eat.”

Soon only four men remained alive, “and we just lay there unable to do a thing. Our appetites and digestions were sound, but our teeth were so loose that we could not eat.” Dead bodies lay scattered around the ship. Two men went ashore and did not return. Munk managed to crawl out of his berth and spent a night on deck, “wrapped in the clothing of those who were already dead.”

The next day, to his astonishment, he saw the two men who had gone ashore upright and walking around. They came across the ice and helped him ashore. Now, for some time, these three “dwelt under a bush on shore, where we built a fire each day.” Whenever they found any greenery, they would dig it up and suck the juice out of its main root. Slowly, incredibly, the three began to recover. They went back aboard ship and found everyone dead. They retrieved a gun and returned to shore, where they shot and ate birds.

Gradually, the three survivors recovered. They reboarded the Unicorn and threw decomposing bodies overboard “because the smell was so bad that we couldn’t stand it.” Then, battling a plague of black flies, they stocked the smaller Lamprey with what food they would need to reach home. Finally, on July 16, Munk writes, “We set sail, in the name of God, from our harbour.”

Such was the navigational skill of Jens Munk that, after battling fog, ice and gale-force winds, he guided the ship through the swirling currents of Hudson Strait and then across the stormy Atlantic. He and his two remaining men reached Norway in late September and their home port of Copenhagen on Christmas Day.

Most accounts of this disaster express wonder that cold and scurvy could take such a toll, wiping out sixty-two of sixty-five men. But an article by Delbert Young, published decades ago in the Beaver magazine, points to poorly cooked or raw polar-bear meat as the likely culprit. Soon after reaching land near present-day Churchill, Manitoba, Munk reported that at every high tide, white beluga whales entered the estuary. His men caught one and dragged it ashore.

Next day, as noted above, a “large white bear” turned up to feed on the whale. Munk shot and killed it. His men relished the bear meat. Again, Munk had ordered the cook “just to boil it slightly, and then to keep it in vinegar for a night.” He had the meat for his own table roasted, and wrote that “it was of good taste and did not disagree with us.”

As Delbert Young notes, Churchill sits at the heart of polar-bear country. Probably, the sailors ate a fair bit of polar-bear meat. During his long career, Munk had seen men die of scurvy and knew how to treat that disease. He noted that it attacked some of his sailors, loosening their teeth and bruising their skin. But when men began to die in great numbers, he was baffled. His chief cook died early in January, and from then on “violent sickness . . . prevailed more and more.”

After a wide-ranging analysis, Young identifies the probable killer as trichinosis—a parasitical disease, unidentified until the twentieth century, which is endemic in polar bears. Infected meat, undercooked, deposits embryo larvae in a person’s stomach. These tiny parasites embed themselves in the intestines. They reproduce, enter the bloodstream and, within weeks, encyst themselves in muscle tissue throughout the body. They cause the terrible symptoms Munk describes and, left untreated, can culminate in death four to six weeks after ingestion. Could trichinosis, induced by raw polar-bear meat, have later played a role in killing some of Franklin’s men? To this we shall return.

After his disastrous misadventure in the North Country, incredibly, Jens Munk began planning another expedition to the same area, this time to establish a fur-trade colony. Not surprisingly, he found it impossible to attract financial backers or crew. He turned to naval activities, commanded fleets to protect Danish shipping and eventually served as an admiral in the Thirty Years War (1618–1648) that engulfed Central Europe.