20.

Lady Franklin Enlists Charles Dickens

On October 23, 1854, the London Times published a front-page report quoting explorer John Rae, who had just arrived back from the Arctic. Rae related how, while crossing Boothia Peninsula with a few men, he had chanced to meet some Inuit hunters. From one of them, he learned that a party of white men had starved to death some distance to the west. Subsequently, he had gleaned details and purchased a variety of articles that placed “the fate of a portion (if not all) of the then survivors of Sir John Franklin’s long-lost party beyond a doubt; a fate as terrible as the imagination can conceive.”

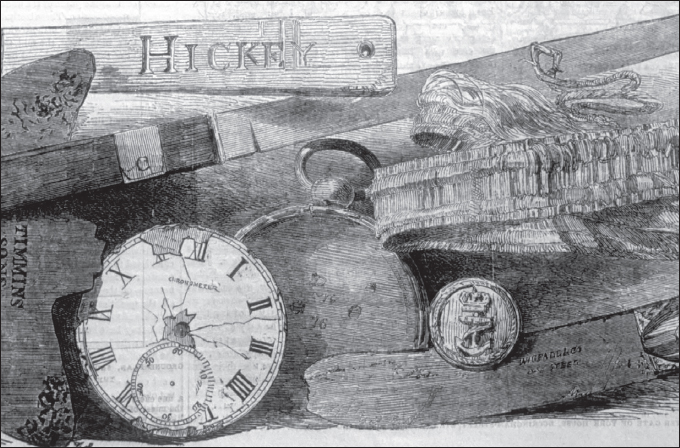

Rae explained that, to secure information, he had offered substantial rewards. At his camp at Repulse Bay, with spring sunshine melting the Arctic ice, he had sat with William Ouligbuck and conducted interviews with visiting Inuit. From them, he collected spoons and broken watches, gold braid, cap bands, a cook’s knife. And he determined that a large party of Franklin’s men had abandoned their ships off King William Island in Victoria Strait. Contrary to all expectations, they had trekked south towards mainland North America, many of them dying as they went.

Some of the Franklin-expedition relics John Rae brought to England, as depicted in The Illustrated London News. When Lady Franklin saw them, she knew that her husband was dead.

One party of Inuit hunters had discovered thirty-five or forty dead bodies. Some lay in tents or exposed on the ground, others under an overturned boat. One man, apparently an officer, had died with a telescope strapped over his shoulder and a double-barrelled shotgun beneath him. Writing for the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Admiralty, rather than a public readership, and accustomed to facing realities beyond the experience of most of his audience, Rae reported the unvarnished truth in words that would resonate around the world: “From the mutilated state of many of the corpses and the contents of the kettles, it is evident that our wretched countrymen had been driven to the last resource—cannibalism—as a means of prolonging existence.”

Rae’s report shook not just Britain but all of Europe. Sir John Franklin and his noble crew had been reduced in the frozen north . . . to cannibalism? Historian Hendrik Van Loon, author of The Story of Mankind, would write that his father, who lived in Holland during this period, forever remembered “the shock of horror that . . . swept across the civilized world.”

Lady Franklin took to her bed. Friends had prepared her, relaying rumours of a preliminary account that had appeared in a Montreal newspaper. That John Franklin had been personally involved in cannibalism she flatly rejected as inconceivable. Even the notion that some of his crew, the flower of the Royal Navy, could be reduced to measures so desperate—no, it exceeded credibility.

Yet, when at the Admiralty offices she examined the relics Rae had brought back from the Arctic—the ribbons, the buttons, the gold braid, the broken watch—Jane Franklin found herself confronting a terrible reality. For nearly ten years she had kept hope alive. Now, as she recognized an engraved spoon that had belonged to Sir John and felt its silver heft in her hand, she felt the truth crash over her like a dark wave. Never again would she see her husband alive.

Late in 1854, Jane Franklin rose from her bed. John Rae’s allegations of cannibalism threatened her husband’s reputation, and so her own. Those assertions could not be allowed to stand. Rae’s relics had convinced her that Franklin had died, but never would she accept the narrative that came with them. When the explorer paid her the obligatory courtesy call, still wearing his full Arctic beard, Jane told him to his face that he never should have accepted the word of “Esquimaux savages,” none of whom claimed to have seen the dead bodies. They were merely relaying the accounts of others. John Rae would not be cowed. He knew the truth when he heard it, and he had written his report not for the Times, but for the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Admiralty. Jane Franklin replied that he should never have committed such allegations to paper.

Eventually, Rae would be vindicated. Down through the decades, researchers would contribute nuance and clarification. But none would repudiate the thrust of his initial report. Some of the final survivors had been driven to cannibalism. Such was the fate of the Franklin expedition.

In 1854, however, Lady Franklin refused to accept this reality. And she had no shortage of allies. These included the friends and relatives of men who had sailed with Franklin, and an array of officers concerned for the reputation of the Royal Navy—men like James Clark Ross, John Richardson and Francis Beaufort. But all of these, she realized, would be open to charges of special pleading.

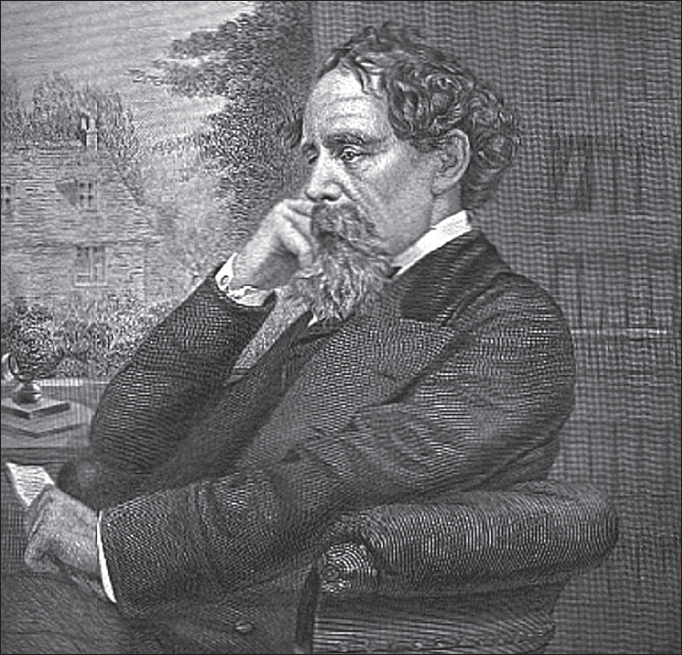

The resourceful lady wondered about Charles Dickens. Hadn’t his father had some connection with the Royal Navy? Surely he could be induced to strike the right attitude? The forty-two-year-old author had already published such classic novels as Oliver Twist, David Copperfield and Bleak House. More importantly, for her purposes, he edited a twice-monthly newspaper called Household Words—potentially the perfect vehicle. Through her friend Carolina Boyle—formerly a maid of honour to Queen Adelaide, the consort of King William IV—Jane communicated her wish that Dickens should call on her as soon as possible.

The desperately busy author dropped everything and, on November 19, 1854, turned up at her front door. No eyewitness account of their meeting has survived. But Jane Franklin wanted John Rae repudiated—especially his allegations of cannibalism—and the greatest literary champion of the age undertook to accomplish that task. The very next morning, Dickens scrawled a note to one W. H. Willis, a sometime assistant. While until now he had paid scant attention to the issue, Dickens observed, “I am rather strong on Voyages and Cannibalism, and might do an interesting little paper for the next No. of Household Words: on that part of Dr. Rae’s report, taking the arguments against its probabilities. Can you get me a newspaper cutting containing his report? If not, will you have it copied for me and sent up to Tavistock House straight away?”

After conferring with Lady Franklin, Charles Dickens decided that he was “rather strong on Voyages and Cannibalism.” He proceeded to publish a shameful two-part screed repudiating John Rae’s report and libelling the Inuit as “savages.” This was probably the worst thing Dickens ever wrote.

Taking his cue from Lady Franklin, Dickens wrote a ferocious two-part denunciation entitled “The Lost Arctic Voyagers.” He published Part One as the lead article on December 2, and Part Two the following week. Acknowledging that Rae had a duty to report what he had heard, and so seeming to demonstrate his even-handedness, Dickens castigated the Admiralty for publishing his account without considering its effects. While exonerating Rae personally, he attacked that explorer’s conclusions, contending that there was no reason whatsoever to believe “that our wretched countrymen had been driven to the last resource—cannibalism—as a means of prolonging existence.”

Given that he could present no new evidence, and had never got anywhere near the Arctic, Dickens argued by analogy and according to probabilities. He suggested that the remnants of “Franklin’s gallant band” might well have been murdered by the Inuit: “It is impossible to form an estimate of the character of any race of savages, from their deferential behaviour to the white man while he is strong . . . We believe every savage to be in his heart covetous, treacherous, and cruel; and we have yet to learn what knowledge the white man—lost, houseless, shipless, apparently forgotten by his race; plainly famine-stricken, weak, frozen, helpless, and dying—has of the gentleness of the Esquimaux nature.”

Dickens offered much more along these lines. He criticized Rae for having taken “the word of a savage,” and, confusing the Inuit with the Victorian stereotype of the African, argued, “Even the sight of cooked and dissevered human bodies among this or that tatoo’d tribe, is not proof. Such appropriate offerings to their barbarous, wide-mouthed, goggle-eyed gods, savages have been often seen and known to make.”

With all the literary skill at his command, Dickens presented an argument that, from the vantage point of the twenty-first century, can only be judged distressingly racist. In this instance, at least, the author failed to transcend the attitudes of his age. Time has proven his two-part essay to be a tour de force of self-deception and wilful blindness. But late in 1854, it engulfed John Rae like an avalanche. The explorer responded as best he could, but he had only truth on his side, and few writers in any time or place could have contended with Charles Dickens in full rhetorical flight. When Dickens was done, in the realm of Victorian public opinion, John Rae was deader than Franklin.

Early in 1855, Lady Franklin began clamouring for more search expeditions. Sir Edward Belcher, having sailed with five ships on what was supposed to be “The Last of the Arctic Voyages,” had arrived back in London. Despite the protests of his senior officers, he had abandoned four of his ships in the Arctic, revealing himself to be both indecisive and cowardly. His outraged subordinate officers saw that he faced a court martial, but he escaped censure, narrowly, because he could point to equivocal orders. Belcher had rescued Robert McClure, but brought no further news of the Franklin expedition.

As for John Rae, Lady Franklin contended that he had left the search area prematurely. Never mind that the winter ice was turning to water and he had no boat on the west coast of Boothia or anywhere near King William Island. Surely the Hudson’s Bay Company, which had sponsored his revelatory expedition, would undertake to complete the task Rae had begun. And what of the British Admiralty? Now that the correct search area had been precisely identified—she accepted the Inuit testimony that suited her—they had a moral obligation to search for more complete answers.

Rae’s evidence that her husband had died in the Arctic intensified Lady Franklin’s sense of urgency. The same was true of the claim, now being advanced even by certain “Arctic people” she counted as friends, that Robert McClure had discovered the Northwest Passage. No sooner had McClure arrived in England than he began asserting that sledging across the ice to a rescue ship constituted a “completion” of the Northwest Passage—and that this accomplishment entitled him to the £10,000 reward for the discovery of a navigable waterway.

Together with Rae’s proof that Franklin had died in the Arctic, McClure’s claim served to clarify Jane Franklin’s course of action. Most of her contemporaries believed—and she encouraged them in this—that she had driven the search for her absent husband because she loved him more than life itself. But for her, determining “the fate of Franklin” was intertwined with the quest for the Northwest Passage—and with establishing that her husband had somehow “discovered” that elusive channel.

On July 20, 1855, the British House of Commons responded to the claim of Robert McClure by striking a parliamentary committee to enquire into Northwest Passage awards. It received several claims, but only those of two Royal Navy men—McClure and, in absentia, John Franklin—received serious consideration. McClure was claiming that he had succeeded by walking across that ice-choked channel, and so should receive the £10,000 award—a sum that, by conservative measure, is today worth more than US$1.3 million.

Lady Franklin faced a complex situation. She could advance a claim on behalf of her late husband only because of the testimony of John Rae. While rejecting his statements regarding cannibalism, she embraced his declarations that Franklin had sailed as far south as King William Island, and that some of his men had reached the North American continent.

To make her case, Lady Franklin realized that she needed to abandon the original criterion of navigability. She could not argue that McClure had failed to discover a passage because he had walked across the frozen sea to a rescue ship. Judging from Rae’s testimony, Franklin had at best achieved something similar, though without the happy ending. The final survivors from his expedition had died, apparently of starvation, while trekking south from their ships to the coast of the continent.

Compelled to accept McClure’s “walk a Passage” argument, Jane Franklin countered with characteristic ingenuity. She introduced the idea that there existed several northwest passages, not just one. She argued that Franklin had discovered his “more navigable” passage first—even though his ships had never emerged at the far end, but had got trapped in an ice-choked channel that would remain impassable for the rest of the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth. To advance this claim, as British author Francis Spufford observed in I May Be Some Time: Ice and the English Imagination, success in discovering the Northwest Passage had to be “carefully redefined as an impalpable goal that did not require one to return alive, or to pass on the news to the world.”

To the awards judges, Jane Franklin wrote that she did not wish “to question the claims of Captain M’Clure to every honour his country may think proper to award him.” She continued: “That enterprising officer is not less the discoverer of a North-West Passage, or, in other words, of one of the links which was wanted to connect the main channels of navigation already ascertained by previous explorers, because the Erebus and Terror under my husband had previously, though unknown to Captain M’Clure, discovered another and more navigable passage. That passage, in fact, which, if ships ever attempt to push their way from one ocean to the other, will assuredly be the one adopted.”

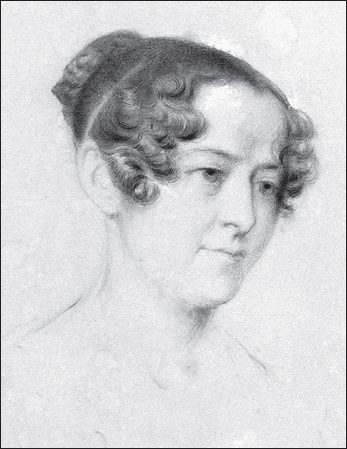

Lady Franklin as she looked in middle age, according to artist Thomas Bock, who drew this portrait in Tasmania using chalk on paper. A third portrait of Jane Franklin does exist, and depicts her sitting in a chair, but it has disappeared into a private collection in Australia.

Never mind that Franklin, too, had got trapped in an ice-choked channel, Victoria Strait, that would remain impassable until well into the twentieth century. The parliamentary committee, however, faced a dilemma. The only logical response would have been to admit that none of the “discovered passages” satisfied the original condition of being navigable. Logic decreed that nobody had yet proven successful in this quest.

Admitting that, however, implied renewing the adventure at considerable cost. At present, such spending was unthinkable: Britain was embroiled in an expensive war against Russia. Instead, the committee declared it “beyond doubt that to Captain McClure belongs the distinguished honour of having been the first to perform the actual passage over water—between the two great oceans that encircle the globe.” One of McClure’s junior officers, Samuel Cresswell, had been the first to reach England, but by Royal Navy convention, he didn’t count. The government awarded McClure a knighthood and £10,000. By returning alive to England, he and his men had provided “a living evidence of the existence of a Northwest Passage.”

Lady Franklin did not concede defeat. She had lost a skirmish, not a war. And she had recognized the wisdom of abandoning navigability as a criterion for discovery of the Passage. Indeed, this latest wrangle had introduced two useful concepts, notable amendments to the original challenge. First, McClure had established that one could “perform” or “accomplish” the Passage without sailing through it. True, by walking across the ice, he had at least completed a transit from one ocean to another—something nobody would ever be able to say of the Franklin expedition. Never mind. Lady Franklin herself had introduced the second corollary notion: several Passages existed, not just one. She would exploit both ideas—and, almost 170 years later, after the discovery of Erebus and Terror, avid apologists would revive both.

Initially, Lady Franklin and her allies held fast to the logic of “walk a Passage.” Sir John Richardson, who had twice travelled with Franklin and later married one of his nieces, coined a poetic phrase to encapsulate the achievement of the expedition’s men: “They forged the last link with their lives.” But the clearest summation came from John Rae. In August 1855, he wrote to Richardson from Stromness, agreeing with his old travelling companion that McClure had been lucky. As for what was said of the matter in the House, Rae declared “it was all balderdash and could only go down with those who knew nothing of the subject.”

Meanwhile, during the summer of 1855, in response to Lady Franklin’s importunities, the Hudson’s Bay Company sent fur trader James Anderson down the Great Fish River to Chantrey Inlet on the Arctic Coast. Acting on a plan devised by John Rae, Anderson travelled the only way he could on such short notice: by canoe. He encountered several Inuit and acquired a few more relics—part of a snowshoe, the leather lining of a backgammon board—but, having failed to acquire a requested Inuit interpreter, he elicited no new detail.

Given Britain’s engagement in the above-mentioned Crimean War, the Admiralty grew increasingly desperate to cease spending on Arctic exploration. To staunch the financial bleeding, the Lords opened a second monetary-awards front. On January 22, 1856, they announced that, within three months, they would decide whether to award the £10,000 prize offered for determining the fate of Franklin. To do so would mean further expeditions were unnecessary. Once again, several claimants stepped forward, among them the whaling captain William Penny, present at the discovery of the Beechey Island graves, and the irrepressible Richard King, who had long ago travelled on one overland journey with George Back: “I alone have for many years pointed out the banks of the Great Fish River as the place where Franklin’s claim could be found.”

Soon after the Admiralty announcement, unaware that Lady Franklin had animated Charles Dickens to write his two-part repudiation of his championing of the Inuit, John Rae called on her once more. Here was a woman who, as Francis Spufford would later observe, “could blight or accelerate careers, bestow or withhold the sanction of her reputation. No other nineteenth-century woman raised the cash for three polar expeditions, or had her say over the appointment of captains and lieutenants.”

John Rae informed Lady Franklin that in Upper Canada, with the help of two expatriate brothers, he had ordered a schooner built. He intended to use any reward money he received to mount yet another Arctic expedition, during which he would seek to acquire more evidence to confirm his report. Although he probably did not mention it, clearly the veteran explorer hoped during that same projected voyage to sail the entire Northwest Passage, using the strait he had discovered to the east of King William Island—the twenty-two-kilometre-wide channel, already known as Rae Strait, through which the Norwegian Roald Amundsen would sail in 1903–1906 while becoming the first to navigate the Passage.

Lady Franklin remained unimpressed. The meeting over, she observed, “Dr. Rae has cut off his odious beard but looks still very hairy and disagreeable.” Nevertheless, she made use of the information she gleaned from the explorer when, in April, she dispatched a long, rigorous letter stressing that the reward had been intended to go “to any party or parties who in the judgement of the Board of the Admiralty should by virtue of his or their efforts first succeed in ascertaining the fate of the expedition.”

Jane Franklin argued first that the fate of her husband’s expedition had not been ascertained because too many questions remained unanswered. She insisted that, even if Rae had ascertained the fate—through those countless interviews and cross-questionings—he had done so not by his efforts, but by chance. By giving the award now, the Admiralty would deny it to those who would rightly earn it. This would create a check or block “to any further efforts for ascertaining the fate of the expedition, and appears to counteract the humane intention of the House of Commons in voting a large sum of money for that purpose.”

Jane Franklin brought her epistle to a stirring climax: “What secrets may be hidden within those wrecked or stranded ships we know not—what may be buried in the graves of our unhappy countrymen or in caches not yet discovered we have yet to learn. The bodies and the graves which we were told of have not been found; the books [journals] said to be in the hands of the Esquimaux have not been recovered; and thus left in ignorance and darkness with so little obtained and so much yet to learn, can it be said and is it fitting to pronounce that the fate of the expedition is ascertained?”

The Lords of the Admiralty would have none of it. They had grown tired of receiving unsolicited advice from Lady Franklin. On June 19, 1856—three months beyond the promised date—the Board notified John Rae that he would receive the award. Rae himself would get four-fifths, and his men would receive the rest.

Lady Franklin had lost another skirmish. Over her protests, and despite her relentless opposition, first Robert McClure and now John Rae had received monetary awards. First the Passage, now the fate—how all occasions informed against her. Was she finished? Had the time come to concede defeat?