24.

Lady Franklin Creates an Arctic Hero

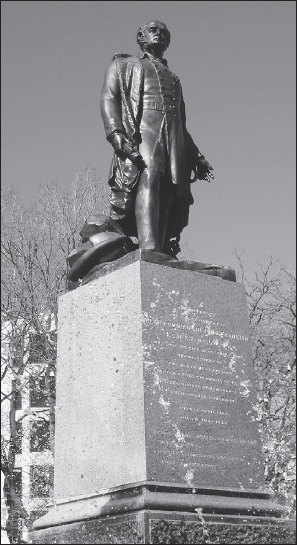

On November 15, 1866, three weeks before she turned seventy-five, an elegantly dressed, petite woman sat in a comfortable, high-backed chair on the second floor of the Athenaeum Club in central London, looking out a window at a ceremonial unveiling in Waterloo Place. Jane, Lady Franklin, her thinning white hair hidden beneath a fashionable bonnet, watched as politicians and senior naval officers clustered around a larger-than-life statue of her dead husband. Created by the well-known sculptor Matthew Noble, the monument identified Sir John Franklin as the discoverer of the Northwest Passage—a circumstance most women would have regarded as a final vindication.

“The moment selected for representation,” the Times would report the next day, “is that in which Franklin has at length the satisfaction of informing his officers and crew that the North West Passage has been discovered. In his hand he grasps the telescope, chart and compasses, and over the full uniform of a naval commander assumed in connection with the important announcement he is in the act of making, he wears a loose overcoat of fur.”

Having herself created that perfect moment, Jane Franklin knew it to be a fiction, and so vulnerable to challenge and contradiction. That was why she had taken such pains with the memorial. Having spent two decades and a small fortune establishing the appropriate mythology—the legend of Sir John Franklin as Discoverer—Jane had left no detail to chance. She had hired the sculptor and stipulated the pose. She had positioned the statue precisely, insisting, after checking the view from this gentlemen’s club, that it be moved back from the street eighteen inches.

Jane Franklin had also supervised the creation of the bas-relief beneath the figure of Franklin, a panel that depicted his second-in-command reading the burial service over a coffin mounted on a sledge. In the background, obscured by mounds of ice, arise the masts of Franklin’s ships, the Erebus and the Terror. Jane had required that the flags be altered to reflect the effects of freezing-cold temperatures. At the base of the statue, she had inscribed the names of the officers and crew of both ships and, in larger letters, the evocative phrase coined by her friend Sir John Richardson: “They forged the last link with their lives.”

Richardson was extrapolating from the work of Leopold McClintock. “Had Sir John Franklin known that a channel existed eastward of King William Land (so named by John Ross),” McClintock wrote, “I do not think that he would have risked the besetment of his ships in such very heavy ice to the westward of it. Had he attempted the north-west passage by the eastern route he would probably have carried his ships through to Behring’s Straits. But Franklin was furnished with charts which indicated no passage to the eastward of King William Land, and he made that land (since discovered by Rae to be an island) a peninsula, attached to the continent of North America; and he consequently had but one course open to him, and that [was] the one he adopted.”

McClintock added that “perhaps some future voyager, profiting by the experience so fearfully and fatally acquired by the Franklin expedition, and the observations of Rae, [Richard] Collinson, and myself, may succeed in carrying his ship through from sea to sea; at least he will be enabled to direct all his efforts in the true and only direction.” In this surmise, McClintock anticipated Roald Amundsen, who would become the first to navigate the Passage in 1903–1906.

But the British naval officer also thought to add, “In the mean time, to Franklin must be assigned the earliest discovery of the Northwest Passage, though not the actual accomplishment of it in his ships.” McClintock was following the line laid down by Lady Franklin. Francis Beaufort, another of the lady’s friends, summarized the cabal’s position: “Let due honours and rewards be showered on the heads of those who have nobly toiled in deciphering the puzzling Arctic labyrinth, and who have each contributed to their hard-earned quota; but let the name of Discoverer of the North-West Passage be forever linked to that of Sir John Franklin.”

Franklin apologists would carry this notion through the twentieth century. And some scholars who recognized its dubiousness would, in effect, shrug. Canadian historian Leslie Neatby explained, for example, that travelling south from Parry Channel, “the true Passage lies to the left of Cape Felix through Ross and Rae Straits, for, once in Simpson Strait, the navigator can hope for reasonably plain sailing along the continental shore to Alaska. The key, then, to the navigable North West Passage lay in the well-concealed waters which separated King William Island from the Boothia Peninsula.” The discovery of the Northwest Passage by John Franklin, Neatby added, “was a point to be judged not by logic, but by sentiment.”

In truth, Franklin discovered no Passage. The man himself died a few months after his ships got trapped in the pack ice. And when his crews marched south to seek help, they forged no link in any chain. They struggled along a permanently frozen strait that constituted no navigable passage; none. In Writing Arctic Disaster, Adriana Craciun argues convincingly that the Franklin expedition “became a cause célèbre because of a preventable disaster, and that in the history of Arctic discoveries Franklin deserves a minor role.” No ship would get through Victoria Strait until 1967, when the icebreaker John A. Macdonald pounded through en route from Baffin Bay to the Beaufort Sea.

Today, because climate change is opening up the entire Arctic archipelago, conventional vessels can often sail through that channel. Yet in 2014, the pack ice there proved impenetrable to the Victoria Strait Expedition, and so forced those involved to proceed south through Rae Strait to focus on the alternative area off Adelaide Peninsula, where they found the Erebus.

Almost alone among her contemporaries, Lady Franklin understood the power of statues, monuments and memorials to shape public opinion and, indeed, to create history. In 1861, she encouraged the Lincolnshire town of Spilsby to erect a statue to her late husband, its most illustrious native son. When a local newspaper suggested an inscription praising Franklin, “who perished in the attempt to discover a North-west Passage,” she quickly vetoed that in favour of a more positive identification: “Sir John Franklin / Discoverer of the Northwest Passage.”

In London, she failed in an effort to have a Franklin memorial installed in Trafalgar Square, one that would match the famous sky-high monument to Admiral Lord Nelson. She settled in 1866 for that larger-than-life statue at Waterloo Place, adjacent to the Athenaeum Club. She finalized the inscription: “To the great Navigator / And his brave companions / Who sacrificed their lives / Completing the discovery of / The North-West Passage / A.D. 1847–48.”

As part of her campaign to make a legend of her husband, Lady Franklin paid for this statue and shipped it to Hobart.

Lady Franklin added an international dimension to the commemoration of Franklin by casting the statue twice. The first copy, a prototype that would reveal any design flaws, she would send to the far side of the world. She had extended this offer to old friends in Tasmania—at last the name “Van Diemen’s Land” had been replaced—and they had undertaken to erect the statue in Hobart. The Franklin memorial in downtown Hobart, with its ornamental pool and spray jets of water, stands today as the most attractive of all the monuments that Lady Franklin built.

The Lady’s machinations required time, energy, perseverance and attention to detail. In 1866, at the Athenaeum Club, while watching the unveiling of the Waterloo Place statue, Jane Franklin allowed herself to savour a partial victory. This statue encapsulated the climax of Arctic discovery, or at least the official version, proclaiming Franklin an indefatigable explorer who had successfully completed a centuries-long quest at the cost of his life. A less ambitious woman, looking out over the ceremony, smiling to see her various surrogates puffed up and vying for pride of place, would have relished this commemoration as a stunning triumph of female sagacity in a world profoundly male. But Jane Franklin felt that her work was not yet done. What of Westminster Abbey? Surely the discoverer of the Northwest Passage deserved to be memorialized in the Abbey, where he would stand among the greatest figures of British history?