25.

Tookoolito and Hall Gather Inuit Accounts

While intently occupied in my cabin, writing, I heard a soft, sweet voice say, ‘Good morning, sir.’ The tone in which it was spoken—musical, lively, and varied—instantly told me that a lady of refinement was there greeting me. I was astonished. Could I be dreaming? No! I was wide awake, and writing. But, had a thunder-clap sounded in my ear, though it was snowing at the time, I could not have been more surprised than I was at the sound of that voice. I raised my head: a lady was indeed before me, and extending an ungloved hand.”

The date: November 2, 1860. The location: on board the George Henry off the east coast of Baffin Island. The writer: Charles Francis Hall, American explorer. The light prevented Hall from seeing his visitor clearly at first: “But, on turning her face,” he wrote, “who should it be but a lady Esquimaux! Whence, thought I, came this civilization refinement?”

Hall was meeting Tookoolito, the younger sister of Eenoolooapik, the Inuk who had visited Scotland in 1839 and helped launch the Baffin Island whale fishery. “She spoke my own language fluently,” Hall wrote, “and there, seated at my right in the main cabin, I had a long and interesting conversation with her. Ebierbing, her husband—a fine, and also intelligent-looking man—was introduced to me, and, though not speaking English so well as his wife, yet I could talk with him tolerably well.”

Together, Tookoolito and Ebierbing—who had spent two years in England and were often called Hannah and Joe—would make one of the most important of all contributions to understanding what had happened to the lost expedition of Sir John Franklin, who was yet to be memorialized even at Waterloo Place. They would teach Hall to adapt to the Arctic, and help him collect Inuit testimony that would finally be recognized as especially crucial after the 2014 discovery of Erebus.

Tookoolito had been born in 1838 at Cape Searle in Cumberland Sound. In 1853, with her husband Ebierbing, and emulating her brother Eenoolooapik, she sailed to England with a whaling captain named John Bowlby. Exhibited at several locations over a period of twenty months, and thanks mainly to Tookoolito’s linguistic abilities, they became a sensation. The Inuit couple dined with Queen Victoria and Prince Albert at Windsor Castle, which, according to Tookoolito, was “a fine place, I assure you, sir.”

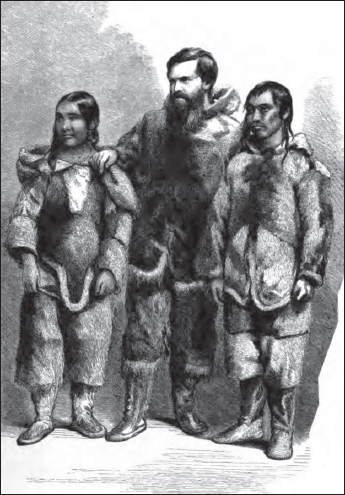

Tookoolito and Ebierbing, shown flanking Charles Francis Hall, made crucial contributions to our understanding of what had happened to the lost expedition of John Franklin.

Bowlby had kept his promise to return the Inuit to Baffin Island. And in 1860, Hall wrote of Tookoolito, “I could not help admiring the exceeding gracefulness and modesty of her demeanor. Simple and gentle in her way, there was a degree of calm intellectual power about her that more and more astonished me.” At first meeting, Hall had asked Tookoolito how she would like to live in England. She answered that she would like that very well. “‘Would you like to go to America with me?’ said I. ‘I would indeed, sir,’ was the ready reply.”

With her husband, Tookoolito would transform the unpromising Hall into a significant figure. In the late 1850s, soon after it appeared, Hall had read Arctic Explorations, Elisha Kent Kane’s two-volume work about his second expedition. Hall, who had apprenticed as a blacksmith before turning to printing two small newspapers in Cincinnati, became convinced that some of Franklin’s men had survived and taken refuge among the Inuit. He felt a sense of vocation, and that God was calling him to go north and rescue those survivors. To do so, he would abandon his pregnant wife and small child.

The man was nearing forty years of age. He had no experience in the North and no qualifications to lead an expedition. But he was bent on searching the area around King William Island and, incredibly, managed to get some financial backing from Henry Grinnell, who had sponsored Kane. Unable to afford a ship, Hall secured free passage to Baffin Island on a whaling vessel, the George Henry. He brought a specially built boat, which he intended to sail west through what he called “Frobisher Strait” as far as he could. Then, having hired Inuit guides, he would continue west by sledge.

Hall left his family and, on May 29, 1860, sailed north out of New London, Connecticut. The ship called at Holsteinborg, Greenland, known today as Sisimiut, and then crossed Davis Strait to Baffin Island, putting in at Cyrus Field Bay on the east coast just north of Frobisher Bay. Now came one of the great synchronicities of exploration history. During that first winter on Baffin, Hall met Tookoolito and her husband, Ebierbing, who began working with him as guides and interpreters.

During the winter of 1861, Hall joined these two and others on a forty-two-day hunting trip, so getting a first taste of building snow huts and driving dogs. Back at camp, Ebierbing’s grandmother—the remarkable Ookijoxy Ninoo, who lived for more than one hundred years—relayed enduring oral stories of white men visiting their lands three years in a row. She described how five of them had spent a winter nearby and then built a boat in which they set out to sail home.

Late the following summer, Hall investigated the location she specified, Kodlunarn Island. He found relics and the foundations of a house dating back to the 1570s and Martin Frobisher. He revisited the island the next summer, and acquired more relics. He made no tangible progress towards his primary objective, but if the Inuit could accurately report events almost three centuries old, surely they could be relied upon to advance the search for Franklin.

In the autumn of 1862, Tookoolito and Ebierbing travelled south with Hall to the United States, where they appeared at his lectures, helping him raise money for another expedition in search of Franklin survivors. Barnum’s American Museum in New York City advertised them as “those wonderful Esquimaux Indians which have arrived from the arctic regions . . . the first and only inhabitants of these frozen regions to visit this country.”

Early in 1863, during an east coast tour, Tookoolito suffered the devastating loss of a new-born son—Tukelieta, Little Butterfly—to pneumonia. She recovered slowly and, in 1864, returned to the Arctic with Hall and her husband. They sailed north in another whaler, the Monticello, bent on launching their search from Repulse Bay, where John Rae had sojourned. Because he debarked too far south, Hall did not reach that destination until June 1865. He set up camp at Fort Hope, where Rae had first wintered almost two decades before.

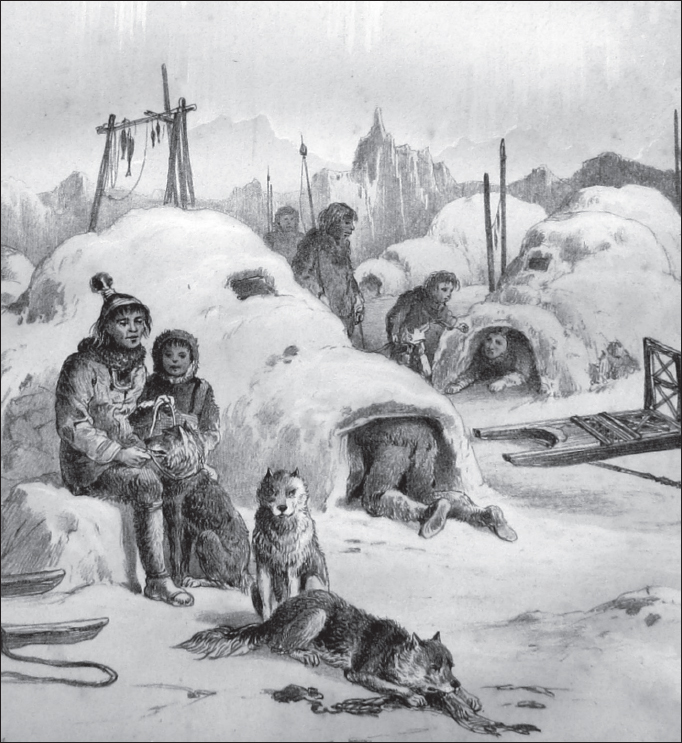

In 1861, during a forty-two-day hunting trip, Charles Francis Hall got his first taste of building snow huts and driving sled dogs.

The team spent three bizarrely frustrating years chasing one false lead after another. In 1866, during a failed expeditionary attempt to reach King William Island, Tookoolito lost a second child—a male Hall had named King William. Finally, in April 1869—after travelling with eight Inuit, among them Tookoolito and her newly adopted daughter, Punna (also known as Punny)—Hall reached Rae Strait and the west coast of Boothia Peninsula. There, with Tookoolito’s help, he interviewed some Inuit who had personally encountered Franklin survivors trekking south, and others who had later discovered dead bodies. From them, he acquired several relics, among them a spoon bearing Franklin’s initials and part of a writing desk.

Hall crossed Rae Strait to King William Island, and in the south, on one of the Todd Islets, he found a complete skeleton. Later, he would send this to England, where leading biologists misidentified it as belonging to Lieutenant Henry Le Vesconte. Recent forensic studies indicate that the remains are those of Harry Goodsir, the Franklin expedition’s physician and scientist. In 1869, Hall wanted desperately to remain on the island into the summer, when disappearing snow might reveal undiscovered relics. But the Inuit hunters had other priorities. The explorer was back at Repulse Bay by June 20, and sailing south soon afterwards, again with Tookoolito and Ebierbing.

Hall’s crucial contribution lies in the accounts he gathered, mainly through Tookoolito, from the Inuit eyewitnesses. These stories, preserved in notebooks and the published Narrative of the Second Arctic Expedition Made by Charles F. Hall, constitute the single most extensive archive of Inuit testimony about the Franklin expedition. Hall was not a clear thinker, nor was he a good writer, but with Tookoolito’s help, he did collect and compile an encyclopedia of material that vindicates John Rae’s reports of cannibalism, and also anticipates and clarifies the recent discovery of Erebus.

Here we encounter horrific tales whose details are so vivid as to be incontrovertible, including references to human flesh cut to facilitate boiling in pots and kettles: “One man’s body when found by the Innuits flesh all on & not mutilated except the hands sawed off at the wrists—the rest a great many had their flesh cut off as if some one or other had cut it off to eat.”

Some Inuit spoke of finding numerous bodies in a tent at what is now called Terror Bay on the west coast of King William Island. One described a woman using a heavy, sharp stone to dig into the ice and retrieve a watch from the body of a corpse: “[The woman] could never forget the dreadful, fearful feelings she had all the time while engaged doing this; for, besides the tent being filled with frozen corpses—some entire and others mutilated by some of the starving companions, who had cut off much of the flesh with their knives and hatchets and eaten it—this man who had the watch she sought seemed to her to have been the last that died, and his face was just as though he was only asleep.”

Without the help of Tookoolito, who did most of the translating, Charles Francis Hall would never have gleaned a single word about the fate of the Franklin expedition.

Hall multiplied gruesome examples, recording tales of finding bones that had been severed with a saw and of skulls with holes in them through which brains had been removed “to prolong the lives of the living.” Hall also met In-nook-poo-zhe-jook, John Rae’s most articulate informant. After talking with Rae, and then learning of McClintock’s visit to the region, this hunter had personally explored King William Island. Hall described him as “very finicky to tell the facts . . . In-nook-poo-zhe-jook has a noble bearing. His whole face is an index that he has a heart kind & true. I delight in his companionship.” Later, the capricious Hall would suggest that “he speaks truth & falsehood all intermingled,” though as David C. Woodman suggests, In-nook-poo-zhe-jook “probably never intentionally told Hall a falsehood.”

At Erebus Bay, the Inuk had located not only a pillaged boat—the one Hobson and McClintock had ransacked for relics—but a second boat, untouched, about one kilometre away. Here, too, he discovered “one whole skeleton with clothes on—this with flesh all on but dried, as well as a big pile of skeleton bones near the fire place & skulls among them.” Bones had been broken up for their marrow, and some long boots that came up as high as the knees contained “cooked human flesh—that is human flesh that had been boiled.”

Late in the twentieth century, while researching Unravelling the Franklin Mystery, Woodman perused Hall’s unpublished field notes. In them, he found testimony elaborating on stories about a shipwreck at the location that McClintock had called Oot-loo-lik, and which Hall transcribed as Ook-joo-lik. According to a local named Ek-kee-pee-ree-a, the ship “had 4 boats hanging at the sides and 1 of them was above the quarter deck. The ice about the ship one winter’s make, all smooth flow, and a plank was found extending from the ship down to the ice. The Innuits were sure some white men must have lived there through the winter. Heard of tracks of 4 strangers, not Innuits, being seen on land adjacent to the ship.”

A woman named Koo-nik, identified as the wife of Seeuteetuar, described the finding of a dead white man on a ship. She reported that several Inuit “were out sealing when they saw a large ship—all very much afraid but Nuk-kee-che-uk who went to the vessel while the others went to their Ig-loo. Nuk-kee-che-uk looked all around and saw nobody & finally Lik-lee-poo-nik-kee-look-oo-loo (stole a very little or few things) & then made for the Ig-loos. Then all the Innuits went to the ship & stole a good deal—broke into a place that was fastened up & there found a very large white man who was dead, very tall man. There was flesh about this dead man, that is, his remains quite perfect—it took 5 men to lift him. The place smelt very bad. His clothes all on. Found dead on the floor—not in a sleeping place or birth (sic).”

Hall asked Koo-nik if she knew “anything about the tracks of strangers seen at Ook-joo-lik?” Some other Inuit had mentioned “walking along the tracks of 3 men Kob-loo-nas & those of a dog with them . . . says she has never seen the exact place not having been further w or w & south than Point C. Grant, which is the Pt. NE of O’Rialy [O’Reilly] Island. She indicates on Rae’s chart the places, recognizing them readily.”

With the help of Tookoolito, Charles Francis Hall gathered a wealth of new information. But he lacked the analytical and imaginative abilities required to develop a coherent revision of the “standard reconstruction” that had evolved from the findings of Rae and McClintock and the one-page Victory Point record.

On September 28, 1869, the Times reported that, after five years in the Arctic, explorer Charles Francis Hall had arrived in New Bedford, Massachusetts. He had discovered the skeletons of several of Sir John Franklin’s party and had returned with relics from the lost expedition. Jane Franklin immediately sent a telegram to Henry Grinnell, asking whether Hall had discovered any writings, journals or letters—any written evidence that her husband had indeed completed a northwest passage. The shipping magnate quickly replied, “None.”

Grinnell sent Lady Franklin a copy of Hall’s report. She found it “so devoid of order and dates as to leave much confusion and perplexity in the mind.” She wished to interview the explorer—in England, if he could be persuaded to visit at her expense, or else in America. She wrote, “If the journals of my husband’s expedition should be brought to light, nothing that reflects on the character of another should be published—nothing that would give sharp pain to any individuals living.”

Leopold McClintock, who considered the fate of Franklin settled to his own everlasting credit, and who feared sensational revelations, wrote to Sophy Cracroft, knowing she would relay his opinion: “I do not see what Lady Franklin can want to see Hall for . . . His report has been moderate for him and I think he is better left alone.”

Lady Franklin would not be deterred. When Hall had returned home to Cincinnati, Ohio, to write a book about his quest, she decided to make an adventure of what would probably be her final trip to North America. In January 1870, Jane Franklin and her niece, Sophy Cracroft, sailed not for New York City but San Francisco, proceeding yet once more around the bottom of South America. Besides the usual maid, they travelled with an efficient manservant named Lawrence, who made this journey—and several that followed—far easier.

In San Francisco, the women boarded a ship sailing north to Sitka, Alaska. That seaside village, situated at latitude 58°, was closer to the Northwest Passage than Jane Franklin had ever come. She and Sophy spent two months in the village—a sojourn that would later be memorialized in Lady Franklin Visits Sitka, Alaska 1870, a 134-page book made up of quotations from Sophy’s journal and contextual articles and appendices.

At last the women journeyed south to Salt Lake City and east to Cincinnati. There, on August 13, 1870, Lady Franklin met Charles Francis Hall. Neither she nor Sophy left any permanent record of this visit—a predictable elision. Jane had already gone on record as believing that, with regard to cannibalism among final survivors of the Franklin expedition, nobody should ever have written a word.

Now, having interviewed the Inuit who discovered the most horrific of the campsites, Hall had recorded many detailed and irrefutable eyewitness accounts. When Lady Franklin arrived, he was compiling these into his soon-to-be published book Life with the Esquimaux: A Narrative of Arctic Experience in Search of Survivors of Sir John Franklin’s Expedition. How much detail did the explorer share with Lady Franklin? Hall had been counselled by his sponsor, Henry Grinnell, to show sensitivity. And he needed Grinnell’s backing for a proposed expedition to the North Pole. Still, Hall would have revealed as much truth to Lady Franklin as he thought she could handle. The truth was that John Rae had been right all along. The final survivors of the Franklin expedition had resorted to eating their dead comrades.

Later, in a letter to Lady Franklin dated January 9, 1871, Hall addressed only tangential issues. The explorer, apologetic, explained that he had lost faith in that “almost holy mission to which I have devoted about twelve years of my life . . . eight of these in the icy regions of the North. What burned with my soul like a living fire, all the time, was the full faith that I should find some survivors of Sir John’s remarkable expedition, and that I would be the instrument in the hands of Heaven, of the solution, but when I heard the sad tale from living witnesses . . . how many survivors in the fall of 1848 had been abandoned to die, my faith till then so strong, was shaken and ultimately was extinguished.”

About this “abandonment”: Hall had interviewed and harshly judged two Inuit hunters, Teekeeta and Ow-wer, who had encountered forty starving men trekking south near Washington Bay on the west coast of King William Island. These two had slipped away instead of somehow rescuing the marchers—as if, in one of the most desolate, animal-empty areas in the Arctic, they could have miraculously produced enough food to sustain so large a party.

As for finding written records, Hall professed hope. He believed that Franklin’s officers had buried them on King William Island before abandoning their ships: “God willing, I will make two more voyages to the North—first for the discovery of the regions about the Pole—and then to obtain the records of Sir John Franklin’s expedition to obtain other information than what I already possess in relation to it.”

For Lady Franklin, this misfit American explorer had already delivered a revelation. At age seventy-eight, and after a lifetime of bending the world to her indomitable will, she had come up against a rock-hard reality she could not reshape. Faced with the detailed narratives of Charles Francis Hall, she could deny the truth no longer. Even the best of Christian men, in order to stay alive, would jettison any religious teaching, cross any moral boundary and resort to any horror. Such was the truth of human nature.

The following January, in response to her request, the explorer sent Lady Franklin two of the original notebooks he had used in preparing his book. Long before those notebooks arrived—indeed, virtually as soon as she spoke with Hall—Jane would have known what they confirmed. And yet, undaunted, she urged the explorer to travel north again and to resume the search for written records.