27.

Ebierbing and Tulugaq Work Magic for Schwatka

Since the mid-nineteenth century, countless investigators—fur traders, sailors, scientists, obsessive amateurs—have added detail and nuance to John Rae’s original report on the fate of the Franklin expedition. In Unravelling the Franklin Mystery, Canadian historian David C. Woodman summed up succinctly: “For one hundred and forty years the account of the tragedy given to Rae by In-nook-poo-zhe-jook and See-u-ti-chu has been accepted and endorsed. As we shall see, it was a remarkably accurate recital of events. But it was not the whole story.”

After 1875, prompted by the death of Lady Franklin, the American Geographical Society decided to send another expedition in search of relics and documents pertaining to the Franklin expedition. Frederick Schwatka, an ambitious lieutenant with the Third United States Cavalry, volunteered to lead it. Born in 1849, Schwatka had been too young to play a role in the American Civil War. When he graduated from West Point in 1871, the military was shedding men.

Schwatka served as a fighting officer in the west, and devoted considerable time to studying the native peoples, ranging among the Apache in the Arizona Territory to the Sioux of the northern plains. He was admitted to the Nebraska bar in 1875 and, the following year, earned his medical degree in New York City.

He was brilliant and practical and, despite his lack of Arctic experience, he won the appointment and sailed from New York on June 19, 1878. His five-man party included “Joe” Ebierbing, the Inuk interpreter who had sailed with Charles Francis Hall and others; an experienced Arctic hand named Frank Melms; and two men who would write books about the expedition—William Henry Gilder of the New York Herald, and Heinrich (Henry) Klutschak, a German artist and surveyor who had emigrated to the United States in 1871.

With Tookoolito dead, Ebierbing sailed north out of New York City with Frederick Schwatka.

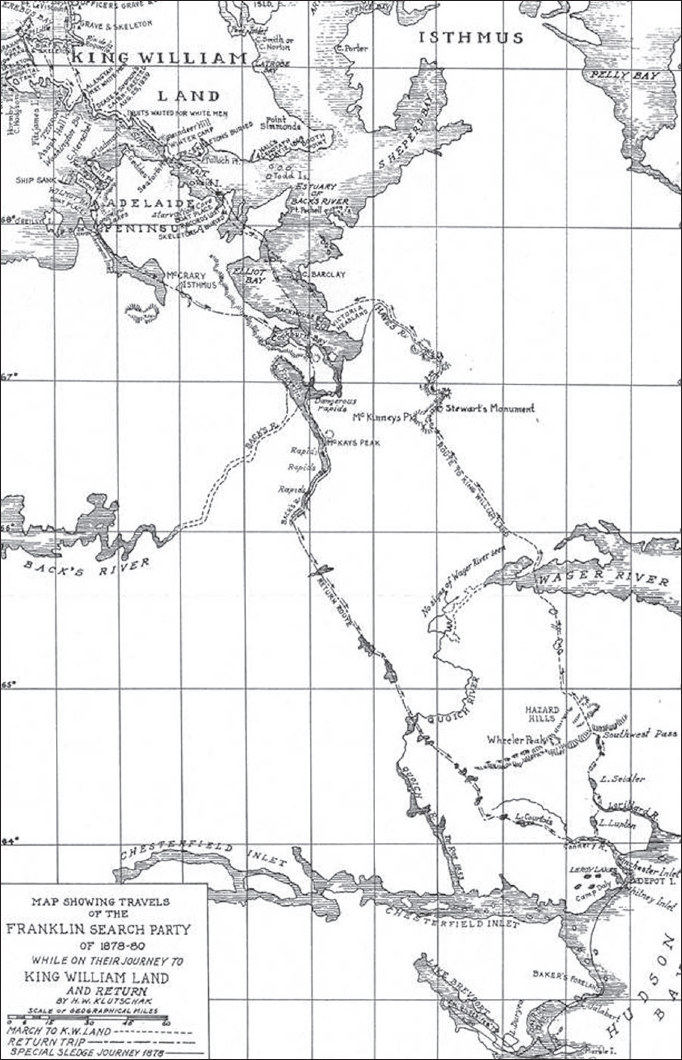

The party set up base camp and spent the winter near Daly Bay, north of Chesterfield Inlet on the coast of Hudson Bay. On April 1, 1879, accompanied by a dozen local Inuit, and with three sledges drawn by more than forty dogs, Schwatka and his men set out for the west coast of King William Island. Over the next year, while relying on an Inuit diet and travel methods, they reached their target destination by accomplishing the longest sledge journey on record: 4,360 kilometres.

Schwatka spent the summer searching the area from the mouth of the Back River to Cape Felix at the northern tip of King William Island. He found bones and relics that would in winter have been covered by snow. William Ouligbuck Jr. had joined the party, and Gilder would verify what John Rae had asserted—that Ouligbuck spoke all the Inuktitut dialects fluently, and that he “spoke the [English] language like a native—that is to say, like an uneducated native.” He and Ebierbing enabled Schwatka to gather an extraordinary amount of crucial Inuit testimony.

But the man who kept the party fed and flourishing was a locally hired Inuk named Tulugaq, a little-known figure who emerges in accounts of the expedition as singular and irreplaceable. As Matonabbee was to Samuel Hearne, so Tulugaq was to Frederick Schwatka: he was the man who made the journey happen. A superlative dogsled driver, he was also, above all, a peerless hunter. When the party located a herd of caribou and Ebierbing, that excellent shot, killed eight of them, Tulugaq bagged twelve.

Eight times, during this year-long Arctic odyssey, Tulugaq killed two caribou with a single shot. At one point, according to Klutschak, he was set upon by a pack of thirty wolves. He leapt onto a high rock and, knowing that wolves will halt any attack to consume their own dead, “with his magazine rifle began providing food for the wolves from their own midst.” When they were distracted, he made his escape.

But Tulugaq’s courage and skill register most memorably in his dealings with polar bears. At Cape Felix, at the northernmost tip of King William Island, Tulugaq used his telescope to locate a bear on the ice roughly nine kilometres away. He hitched up twelve dogs and, with Frank Melms and a youth, set off at a furious pace. When he drew within five hundred paces of the polar bear, the creature turned and fled, making for open water. But Tulugaq had already unleashed three dogs. He then freed three more, and finally the bear had to stand and fight to keep the six dogs at bay.

Crossing Simpson Strait in kayaks. This image of Schwatka and some of his men appeared in The Illustrated London News in 1881.

From twenty-five paces, Tulugaq fired one shot and then another, but the bear, which stood more than ten feet tall, scratched at his head, whirled and came charging at him. Tulugaq’s third shot hit the bear in the heart and brought him down. The hunter dug his first bullet from the bear’s head. Despite the close range, Klutschak writes, “it had not penetrated the bone but had been completely flattened.”

Not long afterwards, when the expedition had finished searching Terror Bay and had travelled more than eighty kilometres south, Tulugaq took a dog team to retrieve some goods left behind at the camp. While travelling, he spotted three bears and gave chase as they fled for open water. As they reached it, Tulugaq shot and killed all three of them with five shots. To take their hides, he then led his female travelling companion in hauling the bears out of the water, each of them weighing at least eight hundred pounds. “For Tulugaq,” Klutschak writes, “nothing was impossible—except transporting the skull of an Inuk.”

On another occasion, Tulugaq spotted a large piece of driftwood in the water. He took some dogs to help him fetch it but, unusually, left his rifle behind. Near the shore, he chanced upon a large female polar bear with a cub three or four months old. He loosed all his dogs and pelted the mother to separate her from her cub. With the dogs at her heels, she took to the water, and Tulugaq used his knife to finish the cub. “Apart from its tenderness,” Klutschak writes, “the cub’s meat had a particularly piquant taste, and we greatly regretted that the old bear had not had twins.”

Tulugaq was also remarkable for his good humour, his willpower and his perseverance, and when Klutschak writes of sadly parting from him, he freely admits that “for a full year we had been indebted to this man for the fact that the execution of our plans had proceeded so well.” What did the expedition accomplish? For starters, on the west coast of King William Island, at a place known as Camp Crozier, Schwatka discovered the remains of Lieutenant John Irving of the Terror, identifiable by the presence of a silver medal for mathematics. He built a cairn at this location and eventually sent the remains to Edinburgh, where they were reburied at an elaborate public ceremony.

At Terror Bay on that same island, where the Terror was coincidentally found, and at Starvation Cove on the mainland near Chantrey Bay, Schwatka found more remains and evidence of cannibalism. With Ebierbing and William Ouligbuck Jr., he interviewed a number of Inuit, eliciting first-person accounts whose crucial importance is emerging only now, in light of the 2014 discovery of the Erebus.

Journey of the Schwatka expedition to the northern coast of King William Island.

Schwatka heard tales of Inuit entering an abandoned ship and accidentally sinking it by cutting a hole in the side, and of papers being distributed among children, buried in sand and blown away by the wind. He gathered complete accounts from several Inuit of their discoveries at Terror Bay, Starvation Cove and Ootjoolik. Gilder’s florid newspaper articles about this expedition, including one that appeared in the New York Herald of October 29, 1880, included headlines such as “Franklin’s Fate Determined”—as if, at last, this expedition had finally finished the job.

Given the 2014 discovery of the Erebus at Ootjoolik (in Wilmot and Crampton Bay, off Grant Point and Adelaide Peninsula), we recognize the special relevance of Schwatka’s interview with Puhtoorak, who went aboard the ship before it sank. We have three accounts of that interview.

According to Gilder, Puhtoorak—“now about sixty-five or seventy”—had only once seen white men alive. As a boy, while fishing on the Back River, “they came along in a boat and shook hands with him. There were ten men. The leader was called “Tos-ard-eroak,” which Joe [Ebierbing] says, from the sound, he thinks means Lieutenant Back. The next white man he saw was dead in a bunk of a big ship which was frozen in the ice near an island about eight kilometres due west of Grant Point, on Adelaide Peninsula. They had to walk out about three miles on smooth ice to reach the ship.”

Around this time, which Gilder estimated to be 1851 or 1852, Puhtoorak saw the tracks of white men on the mainland. Gilder writes that when he first saw them there were four, and afterward only three:

This was when the spring snows were falling. When his people saw the ship so long without any one around, they used to go on board and steal pieces of wood and iron. They did not know how to get inside by the doors, and cut a hole in the side of the ship, on a level with the ice, so that when the ice broke up during the following summer the ship filled and sunk. No tracks were seen in the salt-water ice or on the ship, which also was covered with snow, but they saw scrapings and sweepings alongside, which seemed to have been brushed off by people who had been living on board. They found some red cans of fresh meat, with plenty of what looked like tallow mixed with it. A great many had been opened, and four were still unopened. They saw no bread. They found plenty of knives, forks, spoons, pans, cups, and plates on board, and afterward found a few such things on shore after the vessel had gone down. They also saw books on board, and left them there. They only took knives, forks, spoons, and pans; the other things they had no use for.

Klutschak reprised the story. He wrote that Puhtoorak “was one of the first people to visit a ship which, beset in ice, drifted with wind and current to a spot west of Grant Point on Adelaide Peninsula, where some islands halted its drift.” According to Puhtoorak, then, the ship did not sail to its final location, but was carried there while frozen in the ice. Klutschak notes that “on their first visit [in the autumn] the people thought they saw whites on board; from the tracks in the snow they concluded there were four of them.”

He reiterates how, the following spring, when the whites were gone, the Inuit “found a corpse in one of the bunks and they found meat in cans in the cabin.” He added that “the body was in a bunk inside the ship in the back part.” The Inuit also found “a small boat in Wilmot Bay which, however, might have drifted to that spot after the ship sank.” That boat might also have been left by sailors making a final bid to escape overland.

In Schwatka’s rendition, the Inuit found the tracks first of four white men, and later of only three. Puhtoorak “never saw the white men. He thinks that the white men lived in the ship until the fall and then moved onto the mainland.” When he went on board the ship, Puhtoorak “saw a pile of dirt on one side of the cabin door showing that some white man had recently swept out the cabin. He found on board the ship four red tin cans filled with meat and many that had been opened. The meat was full of fat. The natives went all over and through the ship and found also many empty casks. They found iron chains and anchors on deck, and spoons, knives, forks, tin plates, china plates, etc.” According to Schwatka, Puhtoorak “also saw books on board the ship but the natives did not take them. He afterwards saw some that had washed ashore.”

This Inuit testimony takes on special resonance, obviously, in light of the discovery of Erebus. That was the ship Puhtoorak visited, and these were the stories to which it gave rise. Frederick Schwatka could gather this oral history because he established a rapport with his Inuit informants. Without Ebierbing, who did most of the translating with Puhtoorak, neither Schwatka nor Gilder nor Klutschak would ever have gleaned a word about the Erebus. And without the accounts they relayed, which identified a general location, that ship might never have been found. To the work of Tulugaq, then, must be added that of Ebierbing. Together, those two remarkable Inuit enabled Schwatka to etch his name in the annals of those who elaborated the fate of the Franklin expedition.