29.

The Last Viking in Gjoa Haven

Located in the middle of the Northwest Passage, the hamlet of Gjoa Haven is today home to 1,300 Inuit. In September 1903, when Roald Amundsen put into the bay here in his tiny, one-masted ship, the Gjoa, he felt he had entered “the finest little harbour in the world.” The Norwegian was bent on becoming the first explorer to navigate the Passage from one ocean to another. He hoped also to pinpoint the north magnetic pole. In 1831, more than seven decades before he arrived, and roughly 160 kilometres northwest of Gjoa Haven, James Clark Ross had caught up with that ever-moving pole on the west coast of Boothia Peninsula. Amundsen wanted to determine how far the pole had shifted, and so enable geophysicists to make a comparison.

To that end, on the high ground overlooking the bay, Amundsen set up an evolving series of stations from which to take magnetic observations. He established friendly relations with Inuit who turned up and settled nearby. And he remained through not one but two cold, dark Arctic winters, delaying his epochal voyage for the sake of the Magnetic Crusade.

A view of Gjoa Haven harbour (Uqsuqtuuq) from the Amundsen memorial. On this high hill, Roald Amundsen set up an evolving series of stations from which to take magnetic observations.

Roald Amundsen was born in July 1872 into a substantial, sea-faring family based near Sarpsborg, about ninety-five kilometres south of Oslo. He grew up on the outskirts of the city, then called Christiania. As a boy, he became enthralled with his fellow Norwegian Fridtjof Nansen, who had made the first crossing of the Greenland ice cap and then crossed the Arctic by exploiting the drift of the pack ice. Amundsen began skiing seriously, honing his abilities by undertaking ambitious (and dangerous) cross-country expeditions.

At the same time, he became intrigued by the lost Franklin expedition. His mother wanted him to become a doctor, but after she died in 1893, Amundsen quit university and took to the sea as an ordinary sailor. He qualified as a mate within two years and obtained his master’s licence in 1900. By then he had spent two years as a mate on the Belgica Antarctic expedition led by Adrien de Gerlache, during which he developed a lasting friendship with the American doctor Frederick A. Cook.

Influenced by Nansen, Amundsen grew interested in the scientific dimension of Arctic exploration, especially the mystery of the shifting magnetic poles. He consulted a scientist at the meteorological institute in Christiania, who encouraged him to learn the necessary skills and provided a reference letter. Amundsen travelled south to Hamburg to seek instruction from geophysicist Georg von Neumayer, director of the German Marine Observatory, and the world’s foremost expert on terrestrial magnetism.

Neumayer had been engaging with the shifting poles for more than three decades. In 1857, steeped in the science of Alexander von Humboldt and encouraged by the British naval establishment, he had sailed to Melbourne, Australia, built the Flagstaff Observatory and conducted extensive magnetic studies. Back in Germany, he had become chair of the International Polar Commission and, in the early 1880s, founded the first International Polar Year.

Amundsen described later how in Hamburg, he “hired a cheap room in the poor part of the city.” Next day, “with beating heart,” he presented his letter card to Neumayer’s assistant and was ushered into the presence of a man of about seventy, with “white hair, benign, clean-shaven face, and gentle eyes.” The young man, stammering, said he wanted to go on a voyage and collect scientific data. Neumayer drew him out, and finally Amundsen blurted that he wanted to conquer the Northwest Passage, and also take accurate observations of the north magnetic pole to resolve its mysteries. The white-haired man rose, stepped forward and embraced him. “Young man, if you do that,” he said, “you will be the benefactor of mankind for ages to come. This is the great adventure.”

For three months, Amundsen studied with Neumayer. The older man treated him to dinners and introduced him to scientists and intellectuals. Then, back in Norway, having secured the backing of the influential Nansen, Amundsen set about preparing his dual-purpose expedition. He used a small inheritance to buy a tiny forty-seven-ton sloop, a fishing boat called the Gjoa (seventy feet by twenty). He then devoted two years to training and refurbishing, sailing in the waters east of Greenland while, at the behest of Nansen, conducting oceanographic observations.

Amundsen had difficulty raising enough money to undertake his quest. He borrowed considerable sums. Creditors began threatening to place the Gjoa under lien. On June 16, 1903, with six carefully chosen men, he slipped away, sailing out of Oslo under cover of darkness.

On the west coast of Greenland, at Godhavn (Qeqertarsuaq) in Disko Bay, Amundsen brought aboard twenty “Eskimo” dogs. Then, after acquiring additional provisions and kerosene from Scottish whalers, he sailed across Davis Strait into Lancaster Sound. He proceeded past Beechey Island and swung south into Peel Sound. He battled storms, survived an engine-room fire and, in Rae Strait, sailed too close to shore and nearly ran aground on a submerged rock.

In early September, with winter threatening, Amundsen entered the shelter of Gjoa Haven. Here he spent the next nineteen months, taking continuous magnetic readings. Soon after arriving, and as the ice formed, Amundsen put together a magnetic observatory out of shipping crates built in Norway with copper nails to avoid magnetic interference. He covered this with sod to keep the light from impinging on photographic paper, and used oil lamps for heat. Both Amundsen and his assistant, Gustav Wiik, probably suffered enough carbon monoxide poisoning to damage their hearts. Wiik, who conducted 360 magnetic readings using four different instruments, and so spent by far the most time in the makeshift hut, died on the westward voyage out of the Passage.

Charles Deehr, a space physicist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute, says that the information collected by Amundsen and Wiik is similar to what he collects today from satellites in the so-called “solar wind,” the flow of sun radiation that excites the aurora borealis. Those measurements, Deehr says, “offer more than a glimpse of the character of the solar wind 50 years before it was known to exist.” Quoted by journalist Ned Rozell in the Alaska Science Forum, Deehr said that “Amundsen was the first to demonstrate, without doubt, that the north magnetic (pole) does not have a permanent location, but moves in a fairly regular manner.”

Amundsen’s results, analyzed in 1929, showed that between 1831 and 1904, the north magnetic pole moved fifty kilometres. In the summer of 1905, as he prepared to sail out of Gjoa Haven, Amundsen buried a few artifacts beneath a cairn. Those artifacts, among them a signed photograph of Neumayer, can today be found in Yellowknife at the Prince of Wales Heritage Centre.

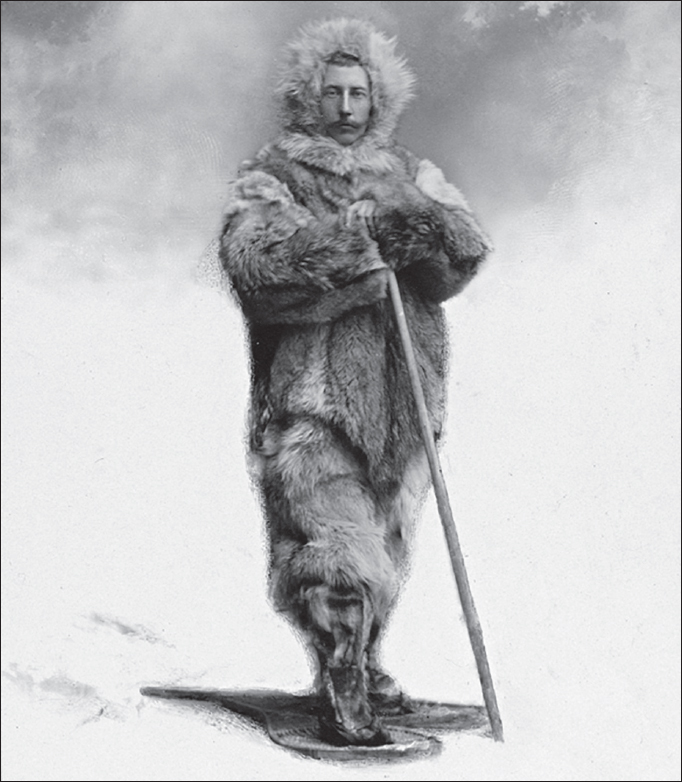

In The Last Viking: The Life of Roald Amundsen, Canadian author Stephen R. Bown remarks that most books treat Amundsen in the context of the 1911 race to the South Pole. That race—which ended with Amundsen becoming the first explorer to reach the Earth’s southernmost point, while British explorer Robert Falcon Scott died trying—certainly makes for a gripping story. But both writers and readers often overlook one crucial fact: Amundsen succeeded because, in addition to training in Norway, he gleaned practical knowledge from the Netsilik Inuit. In November 1903, not long after he arrived in Gjoa Haven, a hunting party came upon the Norwegian visitors. Amundsen established friendly relations and, when the Inuit settled nearby, shared many hunting adventures with them. Like John Rae before him, Amundsen adopted Inuit clothing and footgear, and learned from experts how to travel across ice using dogs and dogsleds, and how to build a warm shelter using blocks of hard snow.

The Inuit helped Amundsen in countless ways. As he entered his second season of darkness, knowing that whalers habitually wintered in the northern reaches of Hudson Bay at Fullerton Harbour, Amundsen wrote a note asking to purchase eight dogs. Late in November 1904, a hunter named Artungelar set out to deliver this request. He travelled with one companion and four dogs, and encountered harsh conditions. Three dogs died along the way, and then, as he neared Fullerton early in March 1905, the Inuk discharged his rifle accidentally and shattered his right hand. He bandaged it up and acquired ten dogs from an American whaler and two Canadians—J. D. Moodie and Joseph-Elzéar Bernier—attached to the Arctic, a Canadian government vessel. Artungelar set out before the end of March and reached Amundsen on May 20, carrying also, from Bernier, some much-appreciated newspaper clippings.

What he learned from the Inuit, notably about dogs, Amundsen brought to his South Pole expedition. By comparison, Robert Falcon Scott could barely ski and, having never met any Inuit, brought ponies to the Antarctic instead of dogs. Thanks to the same quirk of the British psyche that had transformed the plodding, overweight John Franklin into a larger-than-life explorer, Robert Falcon Scott nevertheless became a romantic figure. As Bown writes, he became the embodiment of heroic but doomed struggle, “the man who snatched victory from the jaws of death.” Half a century before Scott, the British had convinced themselves that Franklin and his men, tragically lost in an impassable strait, had somehow “forged the last link with their lives.”

During his two-year sojourn in Gjoa Haven, Roald Amundsen adopted Inuit clothing and learned from experts how to build snow huts and use dogs and dogsleds.

As to actually navigating the labyrinthian Northwest Passage, how did the Norwegian determine which way to sail? Amundsen credited John Rae: “His work was of incalculable value to the Gjoa expedition. He discovered Rae Strait, which separates King William Land from the mainland. In all probability through this strait is the only navigable route for the voyage . . . This is the only passage which is free from destructive pack ice.”

History proved Amundsen correct. As late as 1940–1942, when the Canadian schooner St. Roch became only the second vessel (after the Gjoa) to complete the Northwest Passage, and the first to do so from west to east, Captain Henry Larsen sailed through Rae Strait. And when, in 1944, Larsen managed to return westward through Lancaster Sound and Parry Channel, far to the north, he relied heavily on twentieth-century technology, in the form of a 300-horsepower diesel engine.

In recognizing the crucial importance of Rae Strait, Amundsen recalled the words of Leopold McClintock, who had long ago suggested that if Franklin followed that route, “he would probably have carried his ships through to Behring’s Straits.” Indeed, McClintock anticipated Amundsen when he added that, “perhaps some future voyager, profiting by the experience so fearfully and fatally acquired by the Franklin expedition, and the observations of Rae, [Richard] Collinson, and myself, may succeed in carrying his ship through from sea to sea; at least he will be enabled to direct all his efforts in the true and only direction.”

On August 17, 1905, Roald Amundsen reached Cape Colborne near Cambridge Bay, the easternmost point attained by a ship from the west. By sailing there—almost three hundred kilometres west of where Franklin’s Terror would eventually be found—he had established the viability of the Northwest Passage. A few days later, he encountered a ship, the Charles Hansson out of San Francisco. He hoped to continue into Bering Strait, but ice halted his progress at King Point near Herschel Island. He took magnetic recordings and, over the winter, trekked over the ice to Eagle, Alaska, to send telegrams announcing his accomplishment. He resumed sailing in mid-August 1906, and reached Nome, Alaska, on the thirty-first.

Roald Amundsen achieved more in the Arctic than in the Antarctic. He led the way through the Northwest Passage, and later traversed the Northeast Passage along the Russian coast. In May 1926, he flew an airship over the North Pole, so becoming the first expeditionary leader indisputably to reach it. Amundsen was living at Uranienborg, preparing to marry, when in 1928, at age fifty-five, he flew north to rescue an Italian explorer, Umberto Nobile. He disappeared into the Arctic and was never seen again.