3.

What Thanadelthur Made Possible

Half a century after the Jens Munk debacle, on May 2, 1670, England’s King Charles II waved his magic wand and granted an exclusive trading monopoly over the Hudson Bay drainage basin to “the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England trading into Hudson Bay.” His seven-thousand-word Royal Charter outlined the Company’s rights and duties, which included an obligation to search for the Northwest Passage.

By the early 1700s, when the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) began building Prince of Wales Fort at Churchill, Manitoba, three aboriginal peoples had for centuries been contending to control the mammal-rich hunting grounds to the west and north. These were the Cree, the Dene and the Inuit.

Roughly speaking, allowing for diversity as a result of intermarriages and adoptions, as well as occasional Assiniboine and Ojibway interlopers, some two thousand Swampy Cree made up the vast majority of the “Homeguard Indians” who had settled in the vicinity of HBC trading posts. These Algonquian-speaking people were Western Cree, as distinct from the Eastern Cree, who lived east of Hudson Bay. They were skilful hunters and discerning traders who demanded muskets that worked in winter, and enjoyed playing French traders against British ones. By the 1760s, the Western Cree numbered thirty thousand and ranged westward from Churchill to Lake Athabasca, which is located on the northern border between Saskatchewan and Alberta.

The lands north and west of this vast, Algonquian-speaking territory were dominated by the so-called “Northern Indians.” These Dene, as they called themselves, spoke Athapaskan and had long been rivals and enemies of the Cree. They hunted and fished through most of present-day Northwest Territories, edging into what is now Nunavut.

Subgroups of the Dene were known then as Dogrib and Slavey (sometimes considered one) and Chipewyan, whose name derives from an Algonquian-Cree word referring to the wearing of beaver-skin shirts with backs that narrowed to a point at the bottom, as on a contemporary tailcoat. The Yellowknife or “Copper Indians,” so called because they used copper tools, were a regional subgroup of the Chipewyan, who contested territories traditionally controlled by the Inuit.

Like the Cree, the Dene responded to the demands of the environment by functioning mainly as autonomous extended families. Local bands might include six to thirty hunters, or 30 to 140 persons. Such groupings were often culturally diverse as a result of intermarriages, adoptions and the practice of stealing wives.

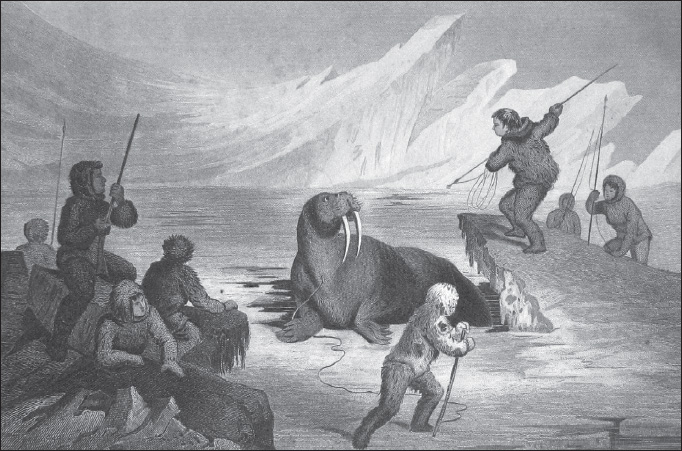

In the treeless, frozen lands that lay still farther north, the Inuit extended across the Arctic from Alaska to Greenland. These “Esquimaux,” as they were called, constituted a single people, as Knud Rasmussen would demonstrate early in the twentieth century. They could understand each other because they spoke related languages: Yup’ik in the west, Inuktitut in the east and Kalaallisut in Greenland. The Inuit hunted caribou, but also fish and sea mammals such as seals, walruses and beluga whales.

The Inuit, armed only with harpoons and knives, found hunting walruses especially challenging in winter, when the crafty creatures made a habit of escaping down ice holes.

The Inuit sometimes came south to Churchill seeking wood and metal. But they did not enjoy friendly relations with the Dene, who were beginning to acquire European muskets and jealously guarded their role as fur traders. Such was the background against which, in the eighteenth century, two radically different Chipewyan-Dene individuals would play crucial roles in the European search for the Northwest Passage and what they called the “Far-Off Metal River,” which today is known as the Coppermine. The first was a woman named Thanadelthur.

In the spring of 1713, a party of well-armed Cree attacked some Chipewyan-Dene and took three young women captive. That autumn, two of the females escaped and hurried westward, hoping to rejoin their people. They survived one winter, but then got lost. In the autumn of 1714, cold and hungry, and with one of them sick, they decided to retreat in the direction of a well-known Hudson’s Bay Company post located a couple of hundred kilometres south of Churchill. This was York Fort, which would become York Factory when a chief factor was stationed there. One of the women died en route.

Five days later, on November 24, the other encountered some HBC men in the wilds. Seventeen-year-old Thanadelthur accompanied these men to York Fort. Governor James Knight, now in his seventies, and formerly the commander of a merchant fleet, quickly realized that she might prove useful. Because the Homeguard Cree were armed with more muskets, Chipewyan fur traders had ceased coming to HBC trading posts. Knight wanted to expand trade into the northwest, and was looking for an interpreter who could make peace between the two peoples.

The highly intelligent Thanadelthur could communicate readily with both Cree and Dene. Over the next few months, she also picked up English. And in June 1715, Knight sent her west on a peacemaking mission with William Stuart, an efficient HBC man, and 150 Homeguard Cree.

Knight commissioned Thanadelthur to inform the Chipewyan that the HBC would soon build a major fur-trading post at Churchill. In addition, because the governor was obsessed with rumours that deposits of copper and “yellow metal,” or gold, existed far to the west, she was to inquire, off-handedly, about minerals. Setting out westward, the travellers ran into problems. The hunting was so poor that, as winter came on, the expedition had to separate into smaller groups.

The multilingual Thanadelthur used her eloquence to create peace between traditional enemies. Ambassadress of Peace: A Chipewyan Woman Makes Peace with the Crees, 1715, oil on board, painted by Francis Arbuckle, 1952.

One party of peacemakers encountered and massacred nine Chipewyans, though later the killers claimed self-defence. When Thanadelthur and Stuart came upon the scene, they were horrified. The young woman, determining that some surviving Chipewyan had headed west, told the innocent Cree with whom she had arrived to wait and, with a few men, set off in pursuit of the survivors. She came upon a few hundred Chipewyan who were gathering to seek revenge. Now she demonstrated her eloquence. Thanadelthur talked for hours and eventually persuaded the Chipewyan to return with her to meet the waiting Cree. They came. The two groups smoked the pipe of peace, and a few Chipewyan returned with Thanadelthur to York Fort, arriving in May 1716.

James Knight was thrilled with how, by “her perpetual talking,” Thanadelthur had established peace between those ancient enemies, the Homeguard Cree and the Chipewyan-Dene. This informal treaty would open the far northwest to Knight himself. Later in the year, Thanadelthur welcomed the governor’s idea of travelling to announce the building of an HBC post at Churchill, and so to solidify the new understanding. Then, around Christmas, she took sick. After a lingering illness, to Knight’s dismay, she died on February 5, 1717.

In his Company journal, Knight wrote lamenting the loss of Thanadelthur’s high spirit, firm resolution and great courage. But he carried on. The Chipewyan warriors she had brought to York Fort had carried knives and copper ornaments. As interpreter, Thanadelthur had relayed their understanding that copper and “yellow metal” could be found along “a far-off metal river.”

Knight went ahead with plans to establish a trading post at the mouth of the Churchill River, to trade with the Chipewyan and possibly the Inuit. He spent a winter there, after constructing a rough, wooden fur-trading post near the former winter quarters of Jens Munk, a few kilometres upriver from where the HBC would later build Prince of Wales Fort.

Knight had long been intrigued by fanciful European maps that showed a northwest passage, identified as “the Strait” or “Straits of Anián,” crossing the continent from north of California to the northeast corner of Hudson Bay. With Thanadelthur, he had asked the visiting Chipewyan-Dene to draw a map of the drainage basin of Hudson Bay. They produced one identifying seventeen rivers. The northernmost river, Knight believed, was the eastern mouth of the Strait of Anián, or the entrance to the Northwest Passage.

In September 1718, Knight sailed to England, bent on mounting an expedition to find the Strait of Anián and the gold and copper of the Far-Off Metal River. Having become a free agent, Knight negotiated the support of the Hudson’s Bay Company. The governing committee agreed to send him to seek the elusive strait and passage through Hudson Bay at a latitude north of 64°. He would also expand trade, investigate the feasibility of establishing a whaling industry and discover the source of those nuggets of copper he had produced as evidence of the existence of precious metals at the mouth of a distant river.

On June 4, 1719, the aging but irrepressible Knight sailed from Gravesend, southeast of London on the River Thames. He left with forty men and two ships, the frigate Albany and the sloop Discovery. Knight and his men sailed into Hudson Bay and were never seen again by white men.

Three years later, in 1722, an HBC captain named John Scroggs made a perfunctory search of the northern reaches of Hudson Bay. He found some wreckage on Marble Island, twenty-five kilometres off the west coast near Chesterfield Inlet, and concluded that both of Knight’s ships had sunk and “every man was killed by the Eskimos.”

Scroggs produced no evidence. But his racist speculation would remain unchallenged for decades. Then the explorer Samuel Hearne, after visiting Marble Island three times, presented a radically different interpretation of what had happened to Knight. In Journey to the Northern Ocean, Hearne described finding guns, anchors, cables, bricks, a smith’s anvil and the foundations of a house, as well as a number of graves. Hearne also discovered “the bottom of the ship and sloop, which lie sunk in about five fathoms of water, toward the head of the harbour.”

He rejected the idea that the Inuit had anything to do with the demise of the expedition, noting that Knight and his men presented no threat. They were also far better armed than the Inuit and would have been invincible. Hearne writes that he interviewed Inuit eyewitnesses, who explained that sickness and famine decimated Knight’s shipwrecked party. Only five sailors survived the first winter. The following summer, three of them died after eating raw whale blubber. The last two men, Hearne wrote, “though very weak, made a shift to bury” their comrades: “Those two survived many days after the rest, and frequently went to the top of an adjacent rock, and earnestly looked to the South and the East, as if in expectation of some vessels coming to their relief. After continuing there a considerable time together, and nothing appearing in sight, they sat down close together, and wept bitterly. At length one of the two died, and the other’s strength was so far exhausted, that he fell down and died also, in attempting to dig a grave for his companion. The skulls and other large bones of those two men are now lying above-ground close to the house.”

For more than two centuries, Hearne’s reconstruction stood as definitive. Who could argue with eyewitnesses? And who could forget the distressing image of those final survivors, scanning the horizon for salvation? The only problem with this evocative rendition is that, two decades after he visited Marble Island, while sitting at his writing desk in London, Samuel Hearne invented it out of whole cloth. In Dead Silence: The Greatest Mystery in Arctic Discovery, authors John Geiger and Owen Beattie make this case at length. The end result, as they observe, was “the most haunting vision of failed discovery in the pageant of Arctic exploration.”

From the vantage point of the twenty-first century, we can see that, while repudiating the racism of Scroggs’s analysis, Hearne oversimplified the expedition’s fate. Subsequent investigations suggest that Knight’s two ships sustained heavy damage in the shallow, rocky harbour at Marble Island. The aging Knight may well have died during the ensuing winter, although the only graves ever found on the island were those of Inuit.

If Knight survived, the obsessive old man might have led his men ashore, then started overland for the Far-Off Metal River, only to perish in what he called “the Barrens.” The most likely scenario, however, is that in the spring of 1720, with their ships incapacitated, Knight’s surviving men piled into their open boats, started rowing towards Churchill, roughly five hundred kilometres south, and perished in the wind and the waves.