31.

Rasmussen Establishes Unity of Inuit Culture

The colourful Greenlandic town of Ilulissat, formerly known as Jacobshavn, faces east towards Disko Island, where in 1845 John Franklin took on fresh water and supplies. At Disko, according to letters sent home to England, Franklin banned swearing and drunkenness. He discharged 5 men and sent them home on supply ships, so reducing his expedition numbers to 129, including himself.

With a population of 4,500, Ilulissat is home to 6,000 sled dogs, many of them noisily in evidence along a boardwalk that leads to spectacular vistas of ice. From a hilltop vantage point at the end of the boardwalk, visitors can look out over the Ilulissat Icefjord, an ice-river that is the largest producer of icebergs in the northern hemisphere. It spawned the iceberg that sank the Titanic, and before that, in the nineteenth century, produced the Middle Ice that gave whalers and explorers so much misery.

The third-largest town in Greenland, Ilulissat is also the most visitor-friendly, and features a multitude of shops. The major in-town attraction is the three-storey Rasmussen museum, originally a vicarage in which Knud Rasmussen was born (in 1879) and spent the first twelve years of his life. Hailed as “the father of Eskimology,” Rasmussen was brave, adventurous, intelligent, efficient, charismatic and persevering. In the history of polar exploration, he is a singular figure: the greatest polar ethnographer of all time. In Ilulissat, numerous exhibits celebrate the man, at once an explorer, a cultural anthropologist and a storyteller who demonstrated, on his Fifth Thule Expedition, that Inuit culture extends from eastern Greenland to Alaska, and also encompasses Siberia.

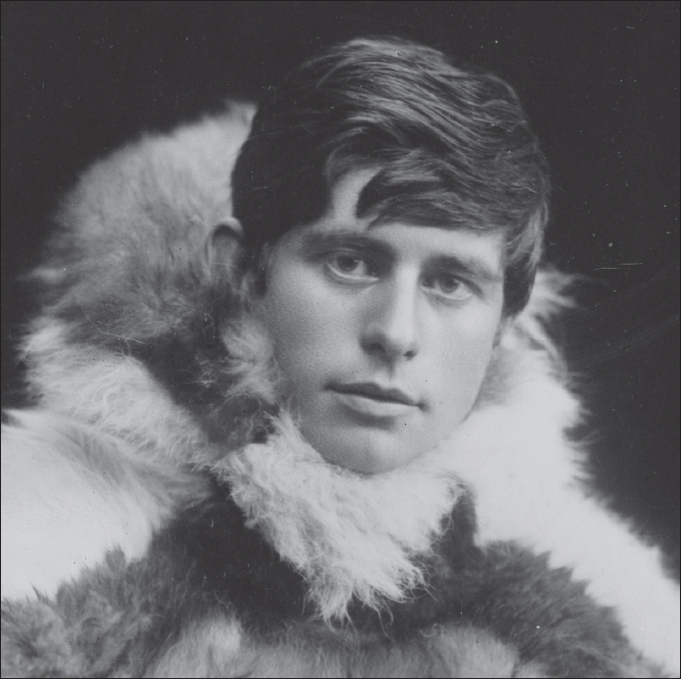

Born in 1879, Knud Rasmussen grew up in this house (then a vicarage) in Ilulissat, Greenland. Today, the house is a museum devoted to Rasmussen, the greatest polar ethnographer of all time.

The son of a Danish missionary and an Inuit-Danish mother, Rasmussen grew up among the Kalaallit (Greenlandic Inuit). As a child he learned to speak Kalaallisut, which is closely related to the Inuktitut spoken by most Canadian Inuit. This would enable him eventually to add to the stock of Inuit stories pertaining to the Franklin expedition. But first, at age seven, he took to driving a dog sledge. “My playmates were native Greenlanders,” he wrote later. “From the earliest boyhood I played and worked with the hunters, so even the hardships of the most strenuous sledge-trips became pleasant routine for me.”

While still a boy, and like his older contemporary Roald Amundsen, he found a hero in explorer Fridtjof Nansen, who had set out from Ilulissat on one of his expeditions. Later, Rasmussen went to Denmark for his education, attending school in the town of Lynge, thirty kilometres north of Copenhagen. At nineteen and twenty, he dabbled without success in acting and singing opera, but then he gravitated to ethnology and the outdoors. In 1902, at age twenty-three, with three fellow Danes, he undertook the so-called Danish Literary Expedition to travel around Greenland studying Inuit culture.

He started by travelling to Kristiania (Oslo) to seek help from Fridtjof Nansen in cutting through red tape. That celebrated explorer recognized Rasmussen’s potential and told him: “Of course, your work does not end with a description of West Greenland and the Smith Sound Eskimos—you must go on to Cumberland and Alaska, and you have benefits like no other researcher before you.”

Because Rasmussen was part Inuit and spoke Kalaallisut, he achieved unprecedented access to Inuit stories and traditions. Ranging throughout the far north Rasmussen would collect stories of fantastical trips to the moon, biographer Stephen Bown tells us—tales “of flesh-eating giants and bears the size of mountains, of evil storm birds and ravenous, human-hunting dogs.” As a “butterfly ethnographer,” Bown notes, Rasmussen evoked “the rich inner world” of a people who stretch across the entire Canadian Arctic.

As a young man, Rasmussen organized the Danish Literary Expedition. With three fellow Danes, he travelled around Greenland studying Inuit culture.

He also detailed one remarkable migration. In 1903, Rasmussen interviewed, for the first time, Merqusaq—one of the last remaining Inuit to have emigrated to Greenland from Baffin Island half a century before. Merqusaq, who had lost one eye, had been born around 1850 in the vicinity of Pond Inlet at the north end of Baffin Island. His extended family of about forty people had arrived there a decade before from Tenudiakbeek or Cumberland Sound, the same whale-rich area that had produced Eenoolooapik and Tookoolito. Pursued by enemies, and led by his uncle Qitlaq, his people crossed Lancaster Sound northward in 1851.

Two years later, at Dundas Harbour on the south coast of Devon Island, they encountered Edward Inglefield, who was searching for John Franklin. Inglefield told them he had seen Inuit on the coast of Greenland, after which, Merqusaq said, Qitlaq “could never settle to anything again.” By 1858, when McClintock passed this way, the charismatic shaman had taken his people still farther north. Despite some defections, Qitlaq then led his family across Smith Sound to Greenland, where in the early 1860s they settled near Etah. Here they met the polar Inuit who had saved Elisha Kent Kane, and who introduced them to the kayak, in which they soon became expert.

Qitlaq died while leading twenty people in an attempted return to Baffin Island. Back on what is now the Canadian side of Davis Strait, his followers were starving when Merqusaq, by then a young married man, came under surprise attack by two men who had gone rogue and become cannibals. One of them gouged out his right eye before he was driven off. Merqusaq and his four closest relatives, fearful of further aggression, fled and eventually made it back to Greenland, where they settled permanently among the polar Inuit. Merqusaq’s granddaughter, Navarana, married Peter Freuchen, Rasmussen’s friend and fellow traveller.

Merqusaq lived with those two during his last years, and Rasmussen would report that, “although old now and somewhat bowed from rheumatism, he continues his journeys of several hundred miles a year on arduous fishing and hunting expeditions.” The ethnographer would quote the renowned hunter: “Look at my body: it is covered with deep scars; those are the marks of bears’ claws. Death has been near me many times . . . but as long as I can hold a walrus and kill a bear, I shall still be glad to live.” Merqusaq died in 1916.

Meanwhile, back in Denmark after his first expedition, Rasmussen gave lectures and wrote The People of the Polar North (1908), which combined a travel narrative with a study of Inuit folklore. In 1910, Rasmussen and Freuchen built the Thule Trading Station at Cape York (Uummannaq), Greenland. From this fur-trading outpost, between 1912 and 1933. Rasmussen organized and launched a series of seven expeditions known as the Thule Expeditions.

On the first of these, Rasmussen and Freuchen set out to test Robert Peary’s claim that a channel divided “Peary Land” from Greenland. By travelling a thousand kilometres over the ice, they proved that this alleged waterway does not exist. Clements Markham, president of Britain’s Royal Geographical Society, hailed this journey as the “finest ever performed by [men using] dogs.” Freuchen would write of it in Vagrant Viking (1953) and I Sailed with Rasmussen (1958).

Starting in 1916, Rasmussen spent two years leading seven men on the Second Thule Expedition, which mapped part of Greenland’s northern coast, and fuelled his book Greenland by the Polar Sea (1921). In 1919, he led the Third Thule Expedition in depot-laying for Amundsen’s polar drift in the Maud. And on the fourth sortie in the series, he spent several months collecting ethnographic data on Greenland’s east coast. All this set the stage for the epochal Fifth Thule Expedition (1921–1924).

On March 10, 1923, from the northern reaches of Hudson Bay, Rasmussen embarked on the longest dogsled expedition in polar history. With two Inuit companions, twenty-four dogs and two narrow sleds, each piled high with a thousand pounds of gear, the Greenlandic Dane set out on the final leg of a 32,000-kilometre trek that would, in his words, “attack the great primary problem of the origins of the Eskimo race.”

Rasmussen had just spent eighteen months exploring parts of Canada west of Hudson Bay. Now, he would spend sixteen months journeying to the east coast of Siberia, where the Russians would deny further access. No matter. On this expedition, Rasmussen became the first explorer to travel through the Northwest Passage by dogsled. The undertaking generated ten volumes of ethnographic, archaeological and biological data, and later inspired the 2006 movie The Journals of Knud Rasmussen. Rasmussen demonstrated that the Inuit, scattered now from Greenland to western Canada and beyond, even into Siberia, constitute a single people.

After leading a seven-person team in doing interviews and excavations on Baffin Island, Rasmussen spent sixteen months with two Inuit hunters, crossing the Arctic to Nome, Alaska. He tells that story in his classic work Across Arctic America (1927). Rasmussen also published numerous articles about his expeditions, and one of them has become especially interesting in light of the 2016 discovery of Terror.

In a 1931 book, The Netsilik Eskimos: Social Life and Spiritual Culture, Rasmussen wrote of interviewing “an old man named Iggiararjuk” who came from Pelly Bay, and told him of a meeting with some of Franklin’s men, probably in the vicinity of Terror Bay, northwest of Gjoa Haven.

My father Mangaq was with Tetqatsaq and Qablut on a seal hunt on the west side of King William’s Land when they heard shouts, and discovered three white men who stood on the shore waving to them. This was in spring; there was already open water along the land, and it was not possible to get in to them before low tide. The white men were very thin, hollow-cheeked, and looked ill. They were dressed in white man’s clothes, had no dogs and were travelling with sledges which they drew themselves.

They bought seal meat and blubber, and paid with a knife. There was great joy on both sides at this bargain, and the white men cooked the meat at once with the aid of the blubber, and ate it. Later one of the strangers went along to my father’s tent camp before returning to their own little tent, which was not of animal skins but of something that was white like snow. At that time there were already caribou on King William’s Land, but the strangers only seemed to hunt wildfowl; in particular there were many eider ducks and ptarmigan then.

The earth was not yet alive and the swans had not come to the country. Father and his people would willingly have helped the white men, but could not understand them; they tried to explain themselves by signs, and in fact learned to know a lot by this means. They had once been many, they said; now they were only few, and they had left their ship out in the pack-ice. They pointed to the south, and it was understood that they wanted to go home overland. They were not met again, and no one knows where they went to.

Rasmussen interviewed several other older men, who added what he called “interesting details of the lost expedition.” Faced with testimony that Louie Kamookak has referred to as “mixed stories,” Rasmussen combined accounts and presented them in the words of one man, Qaqortingneq. He elicited a story that appears to derive mainly from Franklin’s second ship, the Terror. Thanks to a tip from Gjoa Haven resident Sammy Kogvik, who had chanced upon a mast protruding from the winter ice of Terror Bay, that vessel was located in 2016—and has yet to be thoroughly investigated. Rasmussen wrote that two brothers were once out sealing in that vicinity. “It was in spring, at the time when the snow melts away round the breathing holes of the seals. Far out on the ice they saw something black, a large black mass that could be no animal. They looked more closely and found that it was a great ship. They ran home at once and told their fellow villagers of it, and next day they all went out to it. They saw nobody, the ship was deserted, and so they made up their minds to plunder it of everything they could get hold of. But none of them had ever met white men, and they had no idea what all the things they saw could be used for.”

They found guns in the ship, for example, “and as they had no suspicion of what they were, they knocked the steel barrels off and hammered them out for harpoons. In fact, so ignorant were they about guns that they said a quantity of percussion caps they found were ‘little thimbles,’ and they really thought that among the white men there lived a dwarf people who could use them.

“At first they dared not go down into the ship itself,” Rasmussen relates, “but soon they became bolder and even ventured into the houses that were under the deck. There they found many dead men lying in their beds. At last they also risked going down into the enormous room in the middle of the ship. It was dark there.” Now the explorer relays an anecdote that has sometimes been ascribed to the other ship, Erebus. Rasmussen writes that the Inuit “found tools and would make a hole in order to let light in. And the foolish people, not understanding white man’s things, hewed a hole just on the water-line so the water poured in and the ship sank. And it went to the bottom with all the valuable things, of which they barely rescued any.”

According to Rasmussen, Qaqortingneq also described Inuit finding human remains, citing three men who “were on their way from King William’s Land to Adelaide Peninsula to hunt for caribou calves. There they found a boat with the bodies of six men. In the boat were guns, knives and some provisions, showing that they had perished of sickness.”

Rasmussen also describes visiting the mainland that looks out on Wilmot and Crampton Bay, where searchers found Erebus in 2014:

One day in the late autumn,” he writes, “just before the ice formed, I sailed with Peter Norberg and Qaqortingneq up to Qavdlunârsiorfik on the east coast of Adelaide Peninsula. There, exactly where the Eskimos had indicated, we found a number of human bones that undoubtedly were the mortal remains of members of the Franklin Expedition; some pieces of cloth and stumps of leather we found at the same place showed that they were of white men. Now, almost eighty years after, wild beasts had scattered the white, sun-bleached bones out over the peninsula and thus removed the sinister traces from the spot where the last struggle had once been fought.

“We had been the first friends that ever visited the place. Now we gathered their bones together, built a cairn over them and hoisted two flags at half mast, the English and the Danish. Thus without many words we did them the last honours. The deep footprints of tired men had once ended in the soft snow here by the low, sandy spit, far from home, from countrymen. But the footprints were not effaced. Others came and carried them on. So does the work of these Franklin men live on to this day wherever the struggle goes on for the exploration and conquest of our globe.

In 1931, after shuttling between Greenland and Denmark for seven years, lecturing and writing, Knud Rasmussen undertook a Sixth Thule Expedition. It aimed to repudiate the claim of a contingent of Norwegians who had occupied an area on the coast of eastern Greenland, calling it Erik the Red’s Land. It also demonstrated that Greenland’s east coast, long inaccessible, had become reachable between early July and mid-September. In 1933, the Permanent Court of International Justice vindicated Rasmussen and the Danes, and the Norwegians withdrew their claim.

That same year, continuing his work, Rasmussen launched a Seventh Thule Expedition—an ambitious undertaking involving sixty-two members, twenty-five of them Greenlanders in kayaks. Late in 1933, in eastern Greenland, Rasmussen got food poisoning from eating improperly fermented meat. This evolved into a virulent flu and pneumonia. A Danish ship made a special detour to collect Rasmussen and bring him to Copenhagen. Diagnosed as having a rare form of botulism, combined with pneumonia, he rallied for several weeks. But then, in December, at age fifty-four, he succumbed. Denmark accorded him a state funeral, and tributes came from around the world.