4.

Matonabbee Leads Hearne to the Coast

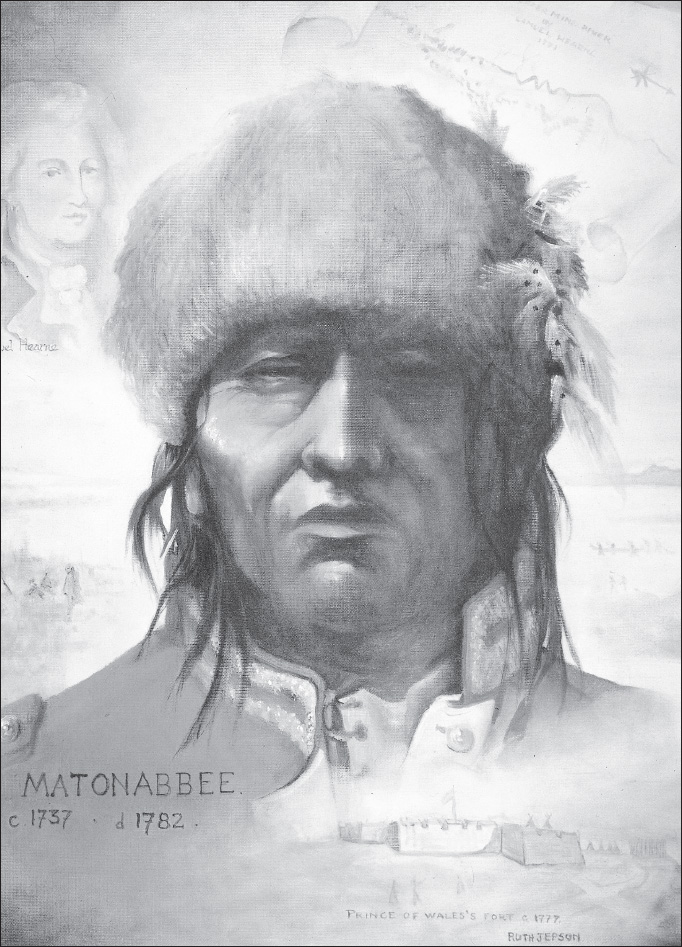

Roughly four decades after the death of Thanadelthur, a second outstanding “Northern Indian,” a man named Matonabbee, began emerging into the saga of northern exploration. In the late 1750s, as an informal HBC ambassador in the tradition of Thanadelthur, Matonabbee reduced hostilities among the native peoples. Born around 1737, the son of a Chipewyan-Dene woman taken captive by the Cree, he had spent his youth in the Churchill area, shuttling among the English-speaking fur traders, the Cree and the Chipewyan. By the early 1760s, he had become a “leading Indian.”

Matonabbee collected furs from Chipewyan-Dene far to the west, and led “gangs” in transporting them to Churchill (Prince of Wales Fort) before setting out again with trade goods. In the autumn of 1770, while returning to the Bay with a dozen men, beating south through cold and howling winds, Matonabbee was astonished to encounter an underdressed HBC man stumbling through the snow with a couple of Homeguard Cree.

Samuel Hearne, a strapping twenty-five-year-old, was equally stunned when Matonabbee addressed him in English. Hearne was six feet tall, and this singular Chipewyan—“one of the finest and best proportioned men I ever saw”—was able to look him almost directly in the eye. When Matonabbee asked how he had fallen into such straits, the young explorer could hardly believe his ears. Could this be the native leader he had originally hoped to find? The one who had not only visited the Far-Off Metal River, but who had brought back copper from its banks?

This portrait of Matonabbee (c. 1737–1782) by Ruth Jepson celebrates the Dene leader as a figure crucial to Samuel Hearne’s epic journey. Without Matonabbee, the English explorer would never have established a first location in the southern channel of the Northwest Passage.

Born in London in 1745, Samuel Hearne grew up with his widowed mother in Beaminster, Dorset, in South West England. In 1757, already a towering youth, Hearne had joined the Royal Navy under the protection of Samuel Hood, a famous fighting captain who later became First Lord of the Admiralty. As a “young gentleman” who walked the quarterdeck, Hearne served with Captain Hood through the Seven Years’ War. He received an excellent eighteenth-century education while learning all he would ever need to know about chasing down and seizing enemy vessels.

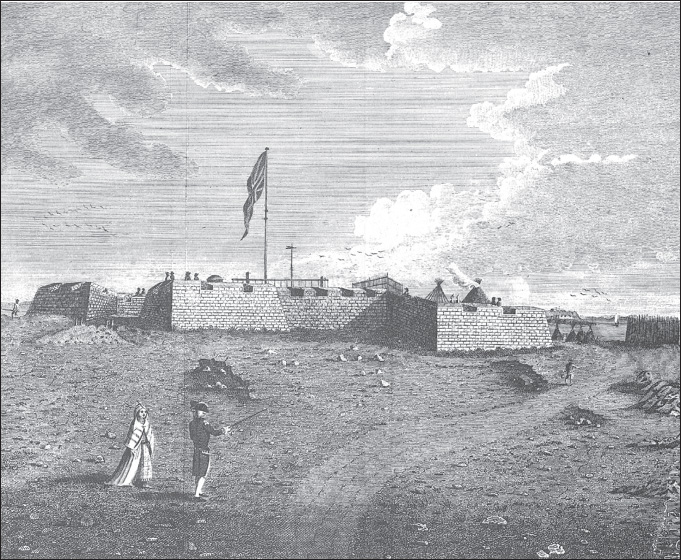

In 1763, when the end of the war closed off any prospect of advancement, Hearne turned to the merchant marine. Early in 1766, seeking adventure and a chance to make his name, the young sailor joined the fur-trading Hudson’s Bay Company, which was looking to expand into whaling. He signed on to serve as first mate on a whaling ship. During the next three years, while based at Prince of Wales Fort, Hearne demonstrated his navigational skills and began learning the languages of the native peoples with whom he came into contact—the Cree, the Dene and the Inuit.

The current HBC governor, Moses Norton, had fallen victim to the obsession of James Knight. He, too, wanted to lay hands on the fabled riches of the Far-Off Metal River. He hoped to accomplish this while answering critics who charged that the HBC was not fulfilling its charter obligations to explore the surrounding countryside. And in 1769, he offered young Hearne the chance to seek the Northwest Passage.

In November, Hearne set out from Churchill with some fellow traders. A guide named Chawhinahaw, paid to lead the party to Matonabbee, instead abandoned them to their own devices. Hearne made it back to Prince of Wales Fort and, in February 1770, set out again, travelling this time with two Homeguard Cree and a party of Dene led by Conneequese. After wending northwest for several months, and getting robbed by passing strangers, Hearne lost his quadrant in an accident. Unable to take the requisite readings, he started back to Churchill and ran into heavy weather. Reduced to shivering and floundering along without snowshoes, he met the one native leader who could appreciate not only how he had come to this, but what he intended still to accomplish.

Respected by both Cree and Dene, and able to move freely among them, Matonabbee knew how to travel in the North Country. He led an ever-changing retinue that included his five or six wives, who carried supplies, cooked meals, sewed clothing and made snowshoes. On December 7, 1770, two weeks after returning with Hearne to Prince of Wales Fort, Matonabbee led the young Englishman out of Churchill.

On this third sortie, the ex–Royal Navy man “went native.” Fitted out with a new quadrant and other supplies, Hearne meant to investigate the mouth of the Far-Off Metal River, and either to discover the Northwest Passage or else disprove its existence. “I was determined to complete the discovery,” he wrote later, “even at the risk of life itself.”

Matonabbee led the party northwest, following the caribou and buffalo. Hearne took notes as he travelled, and later described his harrowing adventure in a work universally recognized as a classic of exploration literature, and best known as Journey to the Northern Ocean. In it, Hearne described Matonabbee as easy, lively and agreeable in conversation, “but exceedingly modest; and at table, the nobleness and elegance of his manners might have been admired by the first personages in the world; for to the vivacity of a Frenchman, and the sincerity of an Englishman, he added the gravity and nobleness of a Turk; all so happily blended, as to render his company and conversation universally pleasing.”

Matonabbee “was remarkably fond of Spanish wines,” he added, “though he never drank to excess; and as he would not partake of spirituous liquors, however fine in quality or plainly mixed, he was always master of himself. As no man is exempt from frailties, it is natural to suppose that as a man he had his share; but the greatest with which I can charge him is jealousy, and that sometimes carried him beyond the bounds of humanity.”

Travelling northwest, Hearne and his fellows lived a cycle of “either all feast, or all famine,” frequently trekking two or three days on nothing but tobacco and snow water. Then someone would kill a few deer and everyone would gorge themselves. On one occasion Matonabbee ate so much that he fell ill and had to be hauled on a sledge. Hearne learned to eat caribou stomachs and raw muskox, and also to endure long fasts that caused him “the most oppressive pain.” He describes travelling through sparse woods comprising stunted pines, dwarf junipers, and small willows and poplars. The travellers followed deer through ponds and swamps, but would stop for days at a time when the hunting was good.

But Hearne’s book is cherished, above all, for its vivid portrait of life among the Chipewyan-Dene of the eighteenth century: “It has ever been the custom for the men to wrestle for any woman to whom they are attached; and, of course, the strongest party always carries off the prize. A weak man, unless he be a good hunter and well-beloved, is seldom permitted to keep a wife that a stronger man thinks worth his notice: for at any time when the wives of those strong wrestlers are heavy-laden either with furs or provisions, they make no scruple of tearing any other man’s wife from his bosom, and making her bear a part of his luggage.

“This custom prevails throughout all their tribes, and causes a great spirit of emulation among their youths, who are upon all occasions, from their childhood, trying their strength and skill in wrestling. This enables them to protect their property, and particularly their wives, from the hands of those powerful ravishers; some of whom make almost a livelihood by taking what they please from the weaker parties, without making them any return. Indeed, it is represented as an act of great generosity, if they condescend to make an unequal exchange; as, in general, abuse and insult are the only return for the loss which is sustained.”

Scarcely a day would pass, Hearne adds, without such a wrestling match. “It was often very unpleasant to me,” he writes, “to see the object of the contest sitting in pensive silence watching her fate, while her husband and his rival were contending for the prize. I have indeed not only felt pity for those poor wretched victims, but the utmost indignation, when I have seen them won, perhaps, by a man whom they mortally hated. On those occasions their grief and reluctance to follow their new lord has been so great, that the business has often ended in the greatest brutality; for, in the struggle, I have seen the poor girls stripped quite naked, and carried by main force to their new lodgings.”

Later, Hearne notes, “I have throughout this account given the women the appellation of girls, which is pretty applicable, as the objects of contests are generally young, and without any family.”

Although these eighteenth-century Northern Indians do not much resemble their contemporary descendants, and would happily rob their fellow travellers not only of their goods but even of their wives, Hearne writes that “they are, in other respects, the mildest tribe, or nation, that is to be found on the borders of Hudson’s Bay: for let their affronts or losses be ever so great, they never will seek any other revenge than that of wrestling. As for murder, which is so common among all the tribes of Southern Indians, it is seldom heard of among them. A murderer is shunned and detested by all the tribe, and is obliged to wander up and down, forlorn and forsaken even by his own relations and former friends.”

This peaceable approach did not extend to people of other nations, as Hearne would discover to his shock and horror. In May 1771, at a place called Clowey Lake, scores of Dene strangers, on learning that Matonabbee was bound for the Far-Off Metal River, attached themselves to his party. They did so “with no other intent,” Hearne wrote later, “than to murder the Esquimaux, who are understood by the Copper Indians to frequent that river in considerable numbers.”

During the past couple of years, while sailing up and down the west coast of Hudson Bay, Hearne had met numerous Inuit. He had mastered the rudiments of their language, and he knew the vast majority of them to be peaceful and good-hearted. At Clowey Lake, he urged his companions to approach these people in peace, as possible trading partners, and not with a view to waging war. The newly arrived Dene reacted with derisive fury, accusing Hearne of cowardice. Perhaps he was afraid to fight the Inuit?

Nearing the Far-Off Metal River, with the warriors clearly preparing an attack, Hearne tried again, and met the same response. He writes: “As I knew my personal safety depended in a great measure on the favourable opinion they entertained of me in this respect, I was obliged to change my tone, and replied, that I did not care if they rendered the name and race of the Esquimaux extinct; adding at the same time, that though I was no enemy of the Esquimaux, I did not see the necessity of attacking them without cause.”

As the only European in the party, Hearne had no hope of averting what was coming. He talked with Matonabbee, but even that leader felt powerless to deflect “the current of a national prejudice which had subsisted between those two nations from the earliest periods, or at least as long as they had been acquainted with the existence of each other.”

In June, leaving behind most of the women and children, Matonabbee and Hearne proceeded northwest with about sixty warriors from various groups, many of whom they had only just met. Trekking through rain, sleet and driving snow, they covered almost three hundred kilometres in sixteen days. With his quadrant, Hearne determined that he was roughly a thousand kilometres northwest of Churchill, although he had travelled more than twice that distance. The party pushed on, and after a final forced march of fifteen or sixteen kilometres, reached the Far-Off Metal River—today’s Coppermine.

It looked nothing like the glorious waterway of legend. Fewer than two hundred metres across, and marked by rocks and shoals, it would never accommodate European ships. Indeed, even canoeists would find it hard to navigate. Hearne spent a couple of days surveying the river. Then, on July 17, 1771, he witnessed one of the most infamous actions in exploration history.

In my book Ancient Mariner: The Amazing Adventures of Samuel Hearne, the Sailor Who Walked to the Arctic Ocean, I devote several pages to analyzing how and why it happened. The bare facts are these. At one o’clock in the morning, after scouts had spotted about twenty Inuit camping by the river, the Dene warriors secretly assembled and waited until the Inuit had retired to their tents. Then they fell upon the sleeping innocents. Hearne writes: “In a few seconds the horrible scene commenced; it was shocking beyond description; the poor unhappy victims were surprised in the midst of their sleep, and had neither time nor power to make any resistance; men, women, and children, in all upwards of twenty, ran out of their tents stark naked, and endeavoured to make their escape; but the Indians having possession of all the landside, to no place could they fly for shelter. One alternative only remained, that of jumping into the river; but, as none of them attempted it, they all fell a sacrifice to Indian barbarity!”

Hearne goes into harrowing detail. “The terror of my mind,” he concludes, “at beholding this butchery, cannot easily be conceived, much less described; though I summed up all the fortitude I was master of on the occasion, it was with difficulty that I could refrain from tears; and I am confident that my features must have feelingly expressed how sincerely I was affected at the barbarous scene I then witnessed.” Hearne adds that even decades later he could not “reflect on the transactions of that horrid day without shedding tears.” He named the site Bloody Falls. In 1996, Dene and Inuit representatives participated in a healing ceremony at the spot, and today it is a territorial park.

In 1771, after tracking the river north for another fifteen kilometres, Samuel Hearne became the first European to reach the Arctic Ocean. At present-day Kugluktuk, he established a first geographical point on the northern coast of North America—and, not incidentally, the first location along what would one day be recognized as the southern channel of the Northwest Passage.

During his pioneering trek, Hearne travelled 5,600 kilometres through uncharted territory, mostly on foot, occasionally by canoe. He did so not as a native, for whom such difficult journeys were commonplace, but as a visitor from another world, an alien creature who managed to adapt and survive and eventually to communicate what he had learned to those at home. Hearne was one of the first to demonstrate that to thrive in the North, Europeans would be wise to apprentice themselves to the native peoples who had lived there for centuries—a strategy that eluded many who followed.

In 1772, back at Prince of Wales Fort, Hearne turned his field notes into an official report. The highly regarded Andrew Graham, acting chief factor at York Fort, appreciated his accomplishment and wrote in support: “Mr. Samuel Hearne, a young gentleman of good education, being employed by the Hudson’s Bay Company to examine the country to the NW of Churchill River, in order to find whether or not there were any passage by water from the Bay to the South Seas; after being absent three years returned, having travelled to Coppermine River . . . without crossing any river worth notice . . . This great undertaking has fully proven that no passage is to be expected by way of Hudson Bay.”

A decade later, in 1782, tragedy struck both Hearne and Matonabbee. With France and England at war, two French warships arrived in Hudson Bay and set about destroying Hudson’s Bay Company posts. With Matonabbee and his warriors at work hundreds of kilometres to the west, the French razed Prince of Wales Fort. They took Hearne and his HBC men prisoner. Having become governor of the Fort, Hearne strove to minimize the impact on the native peoples who remained behind—and especially on his beloved native wife, Mary Norton.

With winter looming, and the French lacking experience in northern waters, Hearne struck a deal: he would guide the invaders through Hudson Strait if they would release him and his men to cross the Atlantic in a small sloop they were towing. Remarkably, with thirty-two men, Hearne made this happen. He succeeded in reaching Orkney and then Portsmouth.

Now he was a man on a mission. The following spring, having amassed materials to rebuild a trading post, he sailed from London on the first ship to Hudson Bay. He was bent on returning to Churchill and resuming life with Mary Norton. Soon after he arrived, however, he learned that, during his absence, the love of his life had starved to death. Then he received a second devastating blow: his best friend, too, was dead. As a “leading Indian,” Matonabbee had flourished with the fur trade. When he arrived back at Prince of Wales Fort and saw the destruction, he believed it to be final. Seeing no way forwards, he hanged himself.

As for Hearne, he spiralled downwards but managed to survive. After five years, he made it back to England. He completed his classic work, which appeared in 1795, three years after he died, as A Journey from Prince of Wales’s Fort in Hudson’s Bay to the Northern Ocean in the Years 1769, 1770, 1771, 1772. The book showed that by reaching the Arctic coast, Hearne had fixed a first point along the southern channel of what would prove to be the only Northwest Passage navigable by ships of that century or the next.

Northwest View of the Prince of Wales Fort in Hudson Bay, engraving from Journey to the Northern Ocean by Samuel Hearne, 1795. The explorer’s original drawing, from 1777, gave rise to this engraving.

Early in the twentieth century, the geologist and fur-trade scholar Joseph B. Tyrrell would introduce a new edition, noting that he considered the work invaluable “not so much because of its geographical information, but because it is an accurate, sympathetic, and patently truthful record of life among the Chipewyan Indians at that time. Their habits, customs and general mode of life, however disagreeable or repulsive, are recorded in detail, and the book will consequently always remain a classic in American ethnology.”

As a gifted natural artist, Hearne also included sketches of Prince of Wales Fort, York Fort and Great Slave Lake, and of many aboriginal artifacts—images that, because they are unique and irreplaceable, continue to turn up in new books on northern history. Hearne did groundbreaking work as a naturalist, devoting more than fifty pages to describing the animals of the Subarctic. He produced the only written record of one of the most controversial moments in Canadian history: the massacre of innocents at Bloody Falls. And with his word-portrait of his best friend, he etched the peerless Matonabbee into the story of northern exploration.