5.

Mackenzie Establishes a Second Location

Like many of his fellow fur traders, rugged men who lived and worked in the North Country, Alexander Mackenzie was keenly interested in the search for the Northwest Passage. But in 1789, when he was preparing to paddle northwest out of Fort Chipewyan, a new fur-trading post at the mouth of the Athabasca River, the history of that search said nothing about Samuel Hearne, whose narrative had yet to be published. Mackenzie had heard rumours that, almost two decades before, while working for the Hudson’s Bay Company, Hearne had “gone native” as he made his way to the mouth of the Coppermine River. He found no gold or copper—nothing of interest. But none of that concerned him.

For Mackenzie, the relevant exploration was that of Captain James Cook, who had sailed from England to seek not the eastern but the western entrance to the Northwest Passage. Someone at the British Admiralty sent him to do so after reading accounts of voyages supposedly undertaken in 1588 and 1640. In the first narrative, a Portuguese mariner named Lorenzo Ferrer Maldonado claimed he had sailed through North America from Davis Strait to the Pacific Ocean. In the second, a man calling himself Bartholomew de Fonte wrote that he had completed the voyage in the opposite direction. Then there was the Greek sailor who claimed that in 1592, using the name Juan de Fuca, he had sailed from the Pacific coast to the Atlantic Ocean and back again.

In 1778, after voyaging in the South Seas, James Cook gave the lie to these tales by charting the west coast of North America from northern Oregon to Alaska. Before heavy ice precluded further progress, he had sailed through Bering Strait to a latitude just above 70°, where on the northwest coast of Alaska he named Icy Cape. Earlier, north of 60°, Cook had explored an inlet with two branches, or arms, which effectively embrace present-day Anchorage. He and his men had determined that a river flowed into each arm of “Cook Inlet,” as it came to be called. Today, we identify those rivers as the Susitna flowing from the north, and the Matanuska from the east.

And when, on June 3, 1789, Alexander Mackenzie paddled northwest out of Fort Chipewyan, he believed he was already on the latter river. If he could reach Cook Inlet by canoe, he could claim discovery of the Northwest Passage—not a waterway navigable by sailing ships, perhaps, but one accessible to brigades of large canoes. He would establish that a continental network of rivers and lakes extended westward from the east to the Pacific Ocean.

Such a discovery would transform the fur trade. Instead of transporting goods thousands of kilometres to and from Montreal, Mackenzie’s business concern, the North West Company, would be able to trade directly with China and Russia, exploiting the Pacific inlet as a fur-trading base the same way its archrival, the Hudson’s Bay Company, used Hudson Bay.

Now twenty-five, Mackenzie had been working in the Montreal-based fur trade for a decade. Five years before, he had taken “a small adventure of goods” west by river to Detroit. These goods he had traded so successfully that his employer had offered him a share in the firm’s profits, on condition that he serve in a post still farther west at Grand Portage, sixty kilometres southwest of present-day Thunder Bay.

The following year, as the company expanded to meet competition, Mackenzie had taken charge of the English River (Churchill) department, based in northern Saskatchewan at Lac Île-à-la-Crosse. In 1787, after his employer joined forces with the North West Company, Mackenzie had ventured still farther north and west to an old fur-trading post on Lake Athabasca.

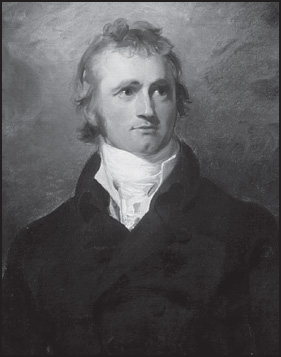

This portrait of Alexander Mackenzie was painted around 1800 by Thomas Lawrence.

At this cluster of rough log cabins in the wilderness, before assuming responsibility for the surrounding area, Mackenzie spent a winter as second-in-command to veteran fur trader Peter Pond, who was soon to retire. Pond believed that at Great Slave Lake, some distance to the north, he had identified the source of a river that flowed to the Pacific coast of the continent. It would culminate, he believed, in one of the two arms of an inlet charted, at latitude 60°, by Captain Cook.

In 1789, after helping to build the splendid Fort Chipewyan, Mackenzie set out to investigate the broad river that flowed northwest out of Great Slave Lake. The optimistic Pond had estimated that from this post, situated at a latitude above 58°, paddlers could reach the Pacific in six or seven days. Each degree of latitude represented about 110 kilometres. But the distance westward might be considerable, and Mackenzie suspected that the journey might take more than a few days. Still, on June 3, when he left Fort Chipewyan with four birch-bark canoes, he felt confident that, within a couple of weeks, he would reach the Pacific coast, and so transform the fur trade while making exploration history.

By this time, three decades after francophone Quebec had become a British colony, Scottish immigrants had gained control of the Montreal-based fur trade. They hired and authorized voyageurs to replace coureurs de bois, who had worked as independent merchants. The vast majority of voyageurs were French Canadians expert in long-distance canoe transportation, and crucial in the rugged northwest. While travelling, they would rise as early as two o’clock in the morning and set off without eating. At around eight, they would stop for breakfast. Then they would paddle, eating pemmican for lunch as they worked, until eight or ten o’clock at night. During a portage, voyageurs would carry two bundles of ninety pounds each, although certain legendary figures were said to have staggered half a mile lugging as many as seven—a total of 630 pounds.

To avoid such arduous trials, and though few of them could swim, voyageurs would often try to run dangerous rapids. The geographer David Thompson (1770–1857) would describe one such occasion, when voyageurs tackled the Dalles des Morts, or Death Rapids, on the Columbia River near present-day Revelstoke, British Columbia. “They had not gone far,” he wrote, soon losing his way in a complex sentence, “when to avoid the ridge of waves, which they ought to have kept, they took the apparent smooth water, were drawn into a whirlpool, which wheeled them around into its Vortex, the Canoe with Men clinging to it, went down end foremost, and all were drowned.” The incident is clear enough.

Now, in 1789, Alexander Mackenzie led a disparate party, but followed no unusual practice. From Fort Chipewyan he embarked with four French-Canadian voyageurs, two of their wives, a German who had been a soldier, a renowned Chipewyan guide known as the “English Chief,” two more wives and two hunters. The women would handle cooking, moccasin sewing, fire building and campsite maintenance, while the men would paddle, hunt, fish and erect tents.

Despite bad weather, Mackenzie set a rapid pace. By rising before dawn and paddling until late afternoon, the travellers reached Great Slave Lake in a week. Here they encountered whirling ice floes, and for two weeks, socked in by rain and thick fog, they sheltered in an abandoned trading post. As the ice slowly cleared, they searched for the outlet of the great river, tormented by swarms of black flies and mosquitoes. Finally, after twenty days on the lake, they discovered the channel they sought. Travelling now with the current, they found paddling easier. Jubilant, they raised their rough sails.

But soon, with a mountain range looming to the west, Mackenzie grew concerned. The river changed direction. Instead of flowing west towards the coastal inlet, it veered north. Mackenzie and his men began coming upon villages of Dogrib people. Several times the explorer hired local guides, but none proved able to point the way westward. Invariably, they slipped away home.

After passing 61°, some distance north of the latitude of Cook Inlet, Mackenzie wrote in his journal that going farther seemed pointless, “as it is evident that these waters must empty themselves into the Northern Ocean.” His fellow travellers urged him to turn back. Curious and obstinate, determined to learn the truth of this waterway, Mackenzie persevered. After a few more days, rolling hills gave way to flat land and the river split into channels.

At last, while encamped on a large island, and after seeing whales, Mackenzie realized that a salt tide washed the shoreline. He had reached the Arctic coast of the continent. From Great Slave Lake, in fourteen days, he had travelled 1,650 kilometres at a rate of more than 110 kilometres per day. Among overland explorers, only Hearne had attained a similar latitude, when he had reached the mouth of the Coppermine River.

By paddling down this greater river—which now bears his name, but which he called River Disappointment—Alexander Mackenzie located a second point along the southern channel of what would prove to be the Northwest Passage. On July 14, 1789, at just above 69° north, he erected a wooden post to mark his achievement.

The return trip, because it was upriver, proved an endurance test. But on September 12, after 102 days on the water, the explorer reached Fort Chipewyan. He was exhausted, but in addition to having discovered the second longest river in North America after the Mississippi, Mackenzie had honed his skills as both traveller and leader.

Four years later, in July 1793, Mackenzie would become the first explorer to reach the Pacific Coast from the east. But the route he followed through the Rockies would prove so dangerous, and feature so many arduous portages, that nobody could ever mistake it for a northwest passage.

In 1801, when Alexander Mackenzie published the journals of his two voyages, he vindicated Samuel Hearne and put paid to any notion that there might be a continent-spanning waterway south of 69°. Any northwest passage would have to be discovered not in the latitudes of Hudson Bay, but in the Arctic waters north of continental North America. And that revelation would interest the British Admiralty.