6.

An Inuit Artist Sails with John Ross

By the early 1800s, British merchants had lost interest in searching for the Northwest Passage. Since the 1570s, they had sponsored expeditions by such adventurers as Martin Frobisher, John Davis, Henry Hudson and William Baffin. Fur-trading concerns had supported the overland searches of Samuel Hearne and Alexander Mackenzie. The Admiralty itself had underwritten the third voyage (1776–1778) of Captain James Cook, who sought the Passage from the Pacific and, in Bering Strait, encountered an impassable wall of ice which, he wrote, “seemed to be ten or twelve feet high at least.”

Today, Cook’s maps and logs speak to the issue of climate change. In 2016, after analyzing them, a University of Washington mathematician determined that, as a phenomenon, a lightning-fast shrinkage of Arctic pack ice began just three decades ago. Harry Stern, quoted in the Seattle Times, said that from Cook’s time until the 1990s, voyagers “could count on hitting the ice somewhere around 70 degrees north in August. Now the ice edge is hundreds of miles farther north.” In the United States, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration confirmed that, since the 1980s, the total volume of Arctic ice in summer has dropped a staggering 60 to 70 percent. Global warming is no hoax.

But pass on. The earliest searchers had demonstrated that, because of the harsh conditions, traversing any northwest passage would at best prove slow and dangerous. Even so, in 1745, the British government established a monetary award for completing the passage. It attracted little interest, and in 1775, the Board of Longitude increased its value. It offered a series of incremental rewards, starting with £5,000 to the first expedition to attain 110° west. The first to reach the Pacific from the Atlantic would receive £20,000.

Still, nobody expressed much interest. Even whalers, who fished annually off Greenland, considered the proposition a bad risk. The quest languished. But then, in 1815, Britain won the decisive Battle of Waterloo, ending a war against Napoleonic France that had been raging sporadically for a dozen years. The Royal Navy found itself with scores of idle ships and hundreds of unemployed officers collecting half-pay. At the British Admiralty, Second Secretary John Barrow, the senior civil servant in charge of the Navy, hit upon geographical exploration as the solution to the excess of both ships and men. Barrow sent an expedition to explore the Congo in West Africa and, when that ended in a yellow-fever catastrophe, turned his attention to the Arctic.

At this point, Great Britain boasted the most powerful navy in the world. But in recent years, the Russians had begun probing the Arctic for a navigable northeast passage. If they proved successful, what a blow to British pride and pre-eminence! What a threat to British trade! Barrow gained political approval to send two Arctic expeditions to seek a route to the Pacific: one to proceed via the North Pole (and the open sea that supposedly encircled it), and the other to sail via Baffin Bay and the Northwest Passage. Each expedition would comprise two ships.

Early in 1818, the Royal Navy began fitting out all four vessels at Deptford, fourteen kilometres south of London. The endeavour became a cause célèbre. In Lady Franklin’s Revenge, I describe how a young London woman organized an outing to Deptford when final inspection was just one week away. On Easter Monday, late in March, twenty-six-year-old Jane Griffin—who would one day be styled “Jane, Lady Franklin”—arrived with a letter of introduction to Commander John Ross, who would lead the Northwest Passage expedition in HMS Isabella.

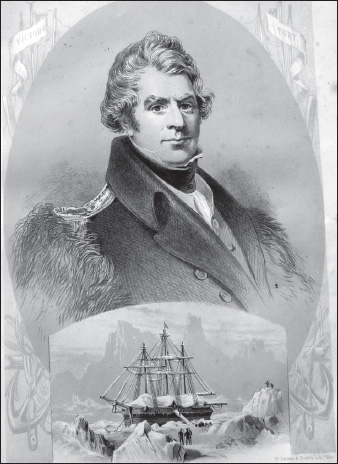

Now forty years old, Ross had joined the Royal Navy at age ten. Of the nine hundred commanders available to the Admiralty, he was one of only nine who, over the past four years, had remained continually employed. He was assured that leading this expedition would secure him a long-sought promotion to captain. The veteran Ross was on his way to becoming Royal Navy royalty, and young Jane Griffin was suitably excited. In her journal, she noted that while the Isabella and the Alexander would seek the Passage under Ross and Lieutenant William Edward Parry, the other two vessels, “the Dorothea, Captain Buchan, and the Trent, Lieutenant Franklin, are going directly to the Pole.”

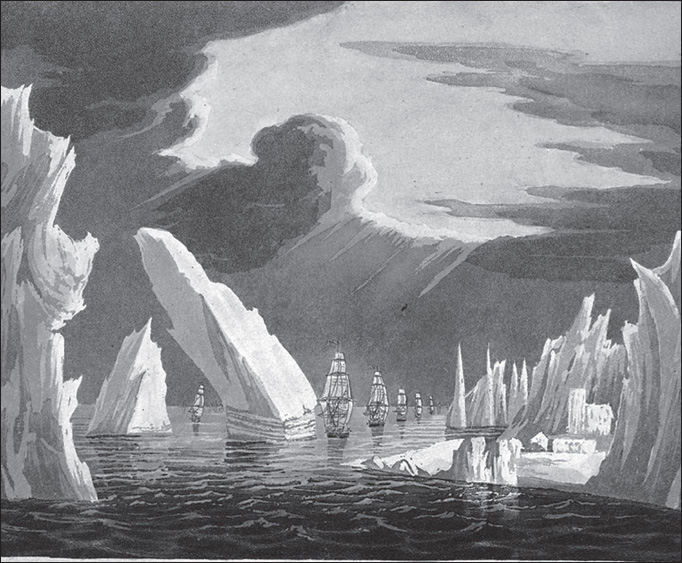

Passage Through the Ice, engraving based on a sketch by John Ross, 1818. Here we see the challenges that mariners faced.

Miss Griffin poked around Ross’s ships below decks and recorded that, although she was only five foot two, she could not stand upright. She saw deal chests filled with coloured beads for trading, as well as harpoons and saws for cutting ice. And she was much taken with a sealskin kayak that belonged to the “Eskimo” who would sail with Commander Ross as interpreter. She regretted having arrived too late to see this English-speaking Inuk, John Sakeouse, demonstrate the use of his kayak.

The kayak was not completely unknown to the British. As early as the 1680s, a well-read Orkney clergyman reported that islanders had spotted some Inuit from Greenland, whom they wrongly called “Finnmen.” James Wallace wrote that the visitors paddled their craft around off one of Scotland’s Orkney Islands (Eday), apparently fishing. They fled when Orcadians sought to approach. Had they crossed the Atlantic by kayak? Perhaps they had sailed aboard a British ship and set out after debarking.

More sightings of Inuit were reported in Orkney (1701) and Aberdeen (1728). But John Sakeouse (Hans Zachaeus) was the first Inuk to enter history by name. He was the first of two hunters to elbow their way into the written record in the first half of the nineteenth century. Born twenty-three years apart, one in southern Greenland, the other in Baffin Island, the two never met. But as young men, both made their way to Scotland. The second we shall meet later.

In 1816, John Sakeouse—as he eventually signed his name to a stipple print—was a resourceful young man, not yet twenty, who befriended some visiting sailors in southern Greenland. With their help, he stowed away (with his kayak) on the Thomas and Anne, a whaling ship. On being discovered, he convinced the captain, a man named Newton, to let him remain aboard and sail to Leith, the main port of Edinburgh.

Why did he leave home? Sakeouse would offer various explanations. Having been converted to Christianity by Danish missionaries, he said, he wanted to see more of the Christian world, and perhaps return one day to educate his people. Better: he had quarrelled with the mother of a young woman he wished to marry and needed to get away. Commander John Ross, with whom he later sailed, suggested that accident played a role: “Sakeouse related many adventures and narrow escapes he had experienced in his [kayak], in one of which he stated himself to have been carried to sea in a storm with five others, all of whom perished, and that he was miraculously saved by an English ship.”

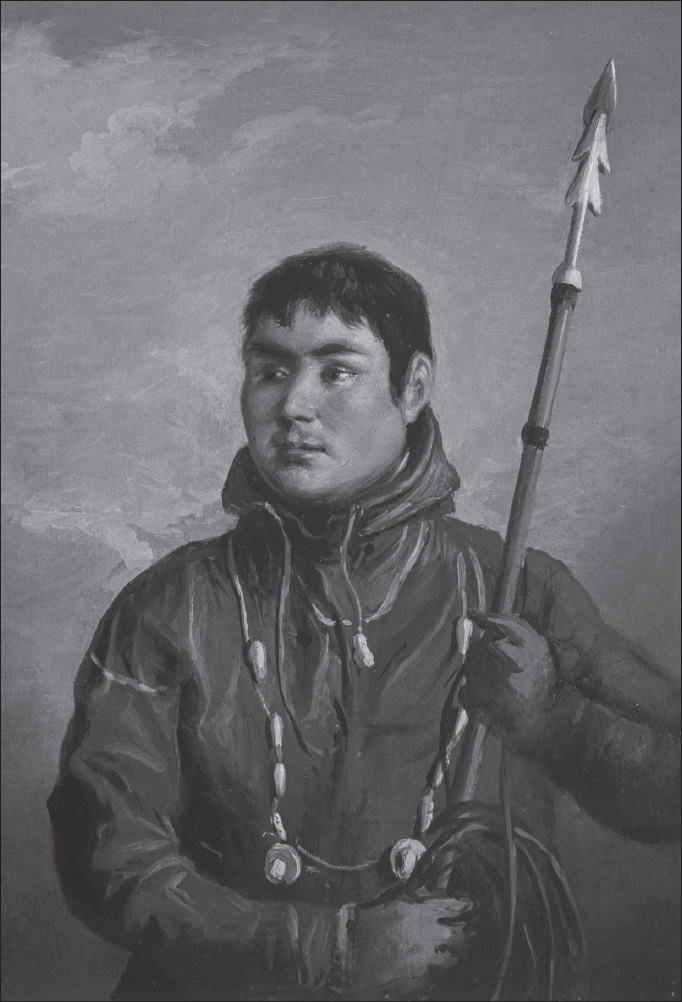

According to the Penny Magazine of the Society for Useful Information, the enterprising Sakeouse was born in 1797. He was “about five feet eight inches high, broad in the chest, and well set, with a very wide face, and a great quantity of coarse black straight hair. The expression of his face . . . was remarkably pleasing and good humoured.”

John Sakeouse, Inuit whaler and artist, enjoyed demonstrating his prowess with a harpoon in the harbour at Leith. Scottish artist Alexander Nasmyth painted this portrait in 1814, when Sakeouse was twenty-two.

During the voyage to Scotland on the Thomas and Anne, he improved his English and learned the ropes as a seaman. In Leith, he became a minor celebrity by demonstrating kayak tricks, among them an underwater roll that proved a crowd-pleaser. The next year, with Captain Newton, he went whaling. But on reaching Greenland, he learned that his beloved sister had died while he was away. Sakeouse insisted on going back to Scotland, and vowed to return home no more.

In Edinburgh, the well-known artist Alexander Nasmyth painted his portrait. Nasmyth discovered that the Inuk “had not only a taste for drawing, but considerable readiness of execution,” and began giving him lessons. On learning that the British Admiralty would soon dispatch a northwest passage expedition under Commander John Ross, he drew their attention to the remarkable young Inuk. The Admiralty offered generous terms. Sakeouse readily accepted, though he stipulated that, as the Penny Magazine put it, “he was not to be left in his own country.”

On April 18, 1818, when the 352-ton Isabella emerged from the River Thames, John Sakeouse was aboard, soon to play a crucial role as interpreter and recorder. By June 3, the Isabella and the 252-ton Alexander had reached the west coast of Greenland. John Ross and Edward Parry could see the central ice pack in Davis Strait, fifteen kilometres to the west, and hugged the open water along the coast as they proceeded north towards Baffin Bay. At Disko Island, near present-day Ilulissat, they found a British whaling fleet of thirty or forty ships, “giving to this frozen and desolate region,” Ross wrote, “the appearance of a flourishing seaport.” The whalers cheered as the naval vessels entered among them.

The Ilulissat Icefjord, an extension of the Greenland ice cap and today a UNESCO World Heritage site, spawns or “calves off” the largest icebergs in the world. “It is hardly possible to imagine anything more exquisite,” Ross wrote. “By night as well as day they glitter with a vividness of colour beyond the power of art to represent.” One calm night, Parry remarked on the serenity and grandeur of the scene: “The water was glassy smooth, and the ships glided among the numberless masses of ice.” The hills of Disko Island reflected “the bright redness of the midnight sun.”

While moored near an island among a number of whaling vessels, and spotting a village of perhaps fifty persons, Commander Ross sent Sakeouse ashore to inquire about doing some trading. The young Inuk returned with seven men and a number of birds. Ross offered them a musket in exchange for a sledge and dogs. The men accepted, went ashore, and promptly returned with a sledge, a team of dogs and five women, two of whom were said to be daughters of a “Danish president” by an Inuit woman.

Ross treated the visitors to coffee and biscuits in his cabin. After leaving the cabin, we learn in The Last Voyage of Captain John Ross, “they danced Scotch reels on the deck with the sailors, during which the mirth and joy of Sakeouse knew no bounds. In his own estimation he was an individual of no little consequence, and certainly an Esquimaux master of ceremonies on the deck of one of his majesty’s ships, in the icy seas of Greenland, was an office somewhat new.”

Ross observed that one of the daughters of the “Danish President, about eighteen years of age, and by far the best looking of the group, was the particular object of the attentions of Sakeouse.” One of the ship’s officers, seeing what was happening, gave the Inuk “a lady’s shawl, ornamented with spangles as an offering for her acceptance.” Sakeouse “presented it in a most respectful, and not ungraceful manner to the damsel, who bashfully took a pewter ring from her finger and gave it to him in return, rewarding him at the same time with an eloquent smile.”

After the festivities, when the visitors left the ship in high spirits, promising to return with more useful goods, Sakeouse escorted them ashore. Next day, when he failed to return, a boat went to fetch him. The young Inuk had broken his collarbone while demonstrating how his gun worked. He had overloaded it to make an impression—“plenty of powder, plenty of kill”—and had failed to anticipate the greater recoil. Apparently, he took some time to heal.

In mid-June, Ross tried and failed to find a way west through the ice pack. Whalers told him that the ice would not begin breaking up for another month, and he resumed heading slowly north along the Greenland coast. For a while he kept company with three whaling ships. But by the end of July, amidst heavy gales and enormous icebergs, the naval vessels were sailing alone. In one storm, the two ships were driven together and nearly crushed. Those sailors who had previously served on whaling ships in the “Greenland service” exclaimed that they owed their lives to the reinforcements done at Deptford, because “a common whaler must have been crushed to atoms.” In 1819, fourteen whaling ships would be smashed here, and in 1830, nineteen.

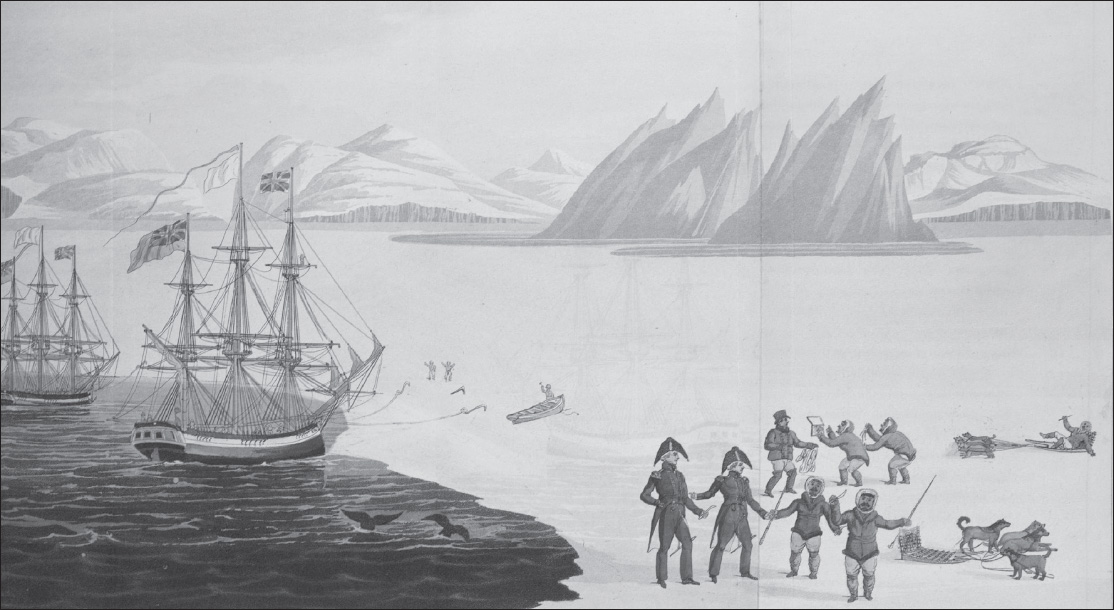

First Communication with the Natives of Prince Regent’s Bay, as drawn by John Sakeouse, 1819. The British naval officers have come onto the ice in their uniforms and the artist entertains the local Inuit by showing them a mirror.

But now the weather calmed. On August 9, while the two ships sailed north through Melville Bay, someone spotted a small group of men gesticulating from the ice between the ship and the shore. John Ross sent a party to make contact, but the men fled on their dogsleds, disappearing among the hummocks. Ross did not give up. In addition to two years’ allowance of food and an array of scientific instruments, he had brought a great many items for trade. These included 2,000 needles, 200 mirrors, 30 pairs of scissors, 150 pounds of soap, 40 umbrellas and 129 gallons of gin.

He placed a cache of goods on shore. This failed to attract visitors, but the following day, the Inuit came charging across the ice, driving eight dogsleds. One mile from the ships, they halted and stood waiting. As a boy, John Sakeouse had heard that northern Greenland was “inhabited by an exceedingly ferocious race of giants, who were great cannibals.” Even so, unarmed, alone, he went out to meet the northerners carrying a white flag. He halted on one side of a great crack or lead in the ice.

After some initial difficulty, Sakeouse found a dialect, Humooke, in which he could communicate with the strangers. They had never before seen a sailing ship or, even from a distance, a white man. Sakeouse tossed the men a string of beads and a checkered shirt. The boldest among them drew a rough-looking iron knife from his boot and told Sakeouse, “Go away, I can kill you.” The visitor threw the man a well-cut British knife: “Take that.” The men pointed to his wool shirt and asked about it. Sakeouse responded that it was made from the hair of an animal they had never seen.

Now the questions came thick and fast. Pointing to the ships, which they took to be alive, they asked if they came from the sun or the moon. Sakeouse said they were floating houses made of wood, but the men said, “No, they are alive. We have seen them move their wings.” Sakeouse said he was a man like them, with a mother and a father, and indicated that he came from a distant country far to the south. The northerners said, “That cannot be, there is nothing but ice there.”

John Ross watched all this through his telescope. He sent out two men with a plank to stretch across the open water separating Sakeouse and the men. Alarmed, they asked that the Inuk should come over alone. They feared that he might be a supernatural creature who could kill them with a touch. Sakeouse insisted that he was a man like them. The bravest touched his hand, and then let out a whoop of joy.

With friendliness established, John Ross gathered more presents and, with Edward Parry, set out across the ice. They emerged in their naval uniforms, complete with cocked hats and tailcoats, and together with Sakeouse, they distributed gifts—beads, mirrors and knives—to a welcoming party that had now grown to eight local men and fifty howling dogs. Soon enough, all the ships’ officers had come ashore, while the crews of both ships stood laughing and shouting encouragement from the bow of the nearest ship, the Alexander.

“The impression made by this scene upon [Sakeouse] was so strong,” according to the Penny Magazine, “that he afterwards executed a drawing of it from memory”—his first historical composition. That drawing, illustrating the first meeting of native northern Greenlanders and British sailors, turned up in John Ross’s book about his voyage. The Beinecke Library declared it “certainly the earliest representational work by a Native American artist to be so reproduced.”

Eventually, Sakeouse convinced the northerners to board the Alexander by climbing a rope ladder. Over the next few days, he and his fellows entertained them, and learned that they had no collective memory of where they came from, and no knowledge even of southern Greenlanders. One of them tried to make off with Commander Ross’s best telescope, a case of razors, and a pair of scissors, but he was spotted and readily returned the articles.

The Greenlanders demonstrated their skill with dogs and sledges, and showed how they hunted foxes using spears they made from narwhal tusks. Seeing the hills and mountains rolling away into the distance, and realizing that these isolated northerners lived in a world of their own, John Ross called them “Arctic Highlanders”—a poetic formulation that would elicit unfair ridicule back in London.

Ross was surprised to learn from Sakeouse that these Inuit had made their own iron knives. With the help of the Inuk, he determined that they chipped the iron off a massive ball that lay on the ground a few days’ journey away. Ross guessed, correctly, that this was a meteorite. Decades later, with the help of local guides, American explorer Robert E. Peary would locate this “Cape York meteorite.” In 1894, he would contrive to carry it off and sell it to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

John Ross didn’t realize it, and would have scoffed at the idea, but his groundbreaking meeting with the polar Inuit—an encounter made possible by John Sakeouse—would prove to be the highlight of his voyage.

In August 1818, he resumed sailing. He followed the same counter-clockwise route that Robert Bylot and William Baffin had pioneered two centuries before. The accuracy of the Bylot-Baffin map of the west coast of Greenland had surprised him. And now he emulated them in making two navigational errors. Near the northwest corner of Greenland, having attained a latitude just above 77°, Ross judged the ice-choked Smith Sound to be a bay. Then, sailing south past Ellesmere Island, he decided the same of Jones Sound. These errors he could have survived. But the next one would culminate in the destruction of his naval career.

On September 1, 1818, after sailing some distance into Lancaster Sound, John Ross judged it to lead nowhere. According to his journal, when a morning fog lifted, he saw “a high ridge of mountains, extending directly across the bottom of the inlet.” His quest for a passage seemed hopeless, but he “was determined completely to explore it, as the wind was favourable; and, therefore, continued all sail.”

The wind abated and, with the Alexander, a poor sailing vessel, several kilometres behind him, he paused and checked the depth: 674 fathoms (1, 213 metres). His orders had stipulated that he should follow any current, and he wrote: “There was, however, no current.” Later, Edward Parry would dispute this, and insist that, in the trailing Alexander, he had registered a noticeable current. Ross noted that the weather was variable. One of his men went up to the crow’s-nest and reported that “he had seen the land across the bay, except for a very short space.”

In 1818, after entering Lancaster Sound, Commander John Ross was fooled by a vivid mirage of a mountain range, and so turned around and sailed for home. This mistake cost him his naval career.

Ross added that, although everyone had by now given up hope of finding a northwest passage, and the weather remained foggy, he “determined to stand higher up,” and possibly locate a harbour in which to make magnetical observations. At three in the afternoon, the officer of the watch told him that the fog was lifting. He immediately went on deck, “and soon after it completely cleared for about ten minutes, and I distinctly saw the land, round the bottom of the bay, forming a connected chain of mountains with those which extended along the north and south sides.”

Ross judged this mountain range to be roughly eight leagues (thirty-eight kilometres) away. He also saw “a continuity of ice, at the distance of seven miles [eleven kilometres], extending from one side of the bay to the other.” At quarter past three, with the fog descending again, “and being now perfectly satisfied that there was no passage in this direction, nor any harbour into which I could enter,” Ross turned around to rejoin the Alexander.

But first, he named the features he had discovered. The mountain range he called the Croker Mountains, after the irascible first secretary of the Admiralty, John Wilson Croker; and the bay before them became Barrow Bay, after the second secretary. And with that, to the dismay, bafflement and outrage of most of his officers, and certainly of Edward Parry, he led the expedition home.

The Croker Mountains do not exist. John Ross had seen a Fata Morgana, a complex, vivid mirage caused by a temperature inversion. This phenomenon is relatively common in the Arctic, but nobody in Victorian England had ever heard of a Fata Morgana. And failing to recognize this one for what it was, an “ice-blink,” cost the veteran sailor his naval career.

None of his officers on either ship had seen the mountain range. Those on the distantly trailing Alexander were astonished when Ross signalled that they were to turn around and sail for home. The science-minded Parry had discerned a powerful current that allowed of only one explanation. He was certain, and soon convinced others, that the expedition had discovered the entrance to the Northwest Passage. He and his fellow officers began voicing their distress even before they arrived back in London on November 16, 1818. From Shetland, in the northern reaches of Scotland, Parry sent a letter to his family: “That we have not sailed through the North-West Passage, our return in so short a period is, of course, a sufficient indication. But I know it is there, and not very hard to find. This opinion of mine, which is not lightly formed, must, on no account, be uttered out of our family; and I am sure it will not, when I assure you that every future prospect of mine depends on it being kept a secret.”

The twenty-seven-year-old Parry wondered if he should dare to contradict one of the most senior officers in the Royal Navy. But soon after arriving in London, summoned to speak with the First Lord of the Admiralty—soon after he had chatted with John Barrow—Parry did precisely that. Afterwards, to his family, unable to contain himself, he wrote: “You must know that, on our late voyage, we entered a magnificent strait, from thirty to thirty-six miles wide, upon the west coast of Baffin’s Bay, and—came out again, nobody knows why! You know I was not sanguine, formerly, as to the existence of a north-west passage, or as to the practicability of it, if it did exist. But our voyage to this Lancaster Sound . . . has left quite a different impression, for it has not only give us reason to believe that it is a broad passage into some sea to the westward . . . but, what is more important still, that it is, at certain seasons, practicable; for when we were there, there was not a bit of ice to be seen.”

Parry, second-in-command of the expedition, was far from alone in taking this view. He had the support of Edward Sabine, a captain in the Royal Artillery and the expedition’s appointed astronomer, and even of James Clark Ross, the eighteen-year-old nephew of John Ross, who had sailed as a midshipman on the Isabella. In 1819, after John Ross published his journal as A Voyage of Discovery, John Barrow wrote a blistering, fifty-page critique in the Quarterly Review, denouncing Ross for, among other things, his lack of perseverance: “A voyage of discovery implies danger; but a mere voyage like this, round the shores of Baffin’s Bay, in the summer months, may be considered as a voyage of pleasure.”

Drawing on Parry’s private journal, Barrow lambasted Ross’s decision to turn back in Lancaster Sound “at the very moment which afforded the brightest prospect of success.” Sabine weighed in with further criticism, accusing Ross of plagiarism and misrepresentation. In December 1818, before this controversy reached a crescendo, Ross had received the promised promotion from commander to captain. But Barrow ensured that, for the Royal Navy, he would never sail again.

The British Admiralty recognized that on his first voyage, John Sakeouse had made a singular contribution. The governing board proposed to send the Inuk on another Arctic expedition under Lieutenant Edward Parry. In London, while sorting out details, the Penny Magazine tells us that Sakeouse took “great delight in relating his adventures with the ‘Northmen.’” Always able to laugh at himself, he alluded “with great good humour and somewhat touchingly . . . to his own ignorance when first he landed in this country. He then imagined the first cow he saw to be a wild and dangerous animal, and hastily retreated to the boat for the harpoon, that he might defend himself and his companions from this ferocious-looking beast.”

Sakeouse became so popular in London drawing rooms that his friends feared “either that the poor fellow’s head would be turned, or that he would get into bad company and acquire dissipated habits.” He soon tired of the big city, however, and returned to Edinburgh to live among his old friends.

The Admiralty Board, not known for free spending, sent money north, stipulating that Sakeouse “be educated in as liberal a manner as possible.” The young man welcomed this initiative, and applied himself to his courses “with astonishing ardour and perseverance.” The artist Alexander Nasmyth resumed teaching him art, and introduced Sakeouse to his own family. Another man traded English lessons for instruction in Inuktitut. Sakeouse enjoyed meeting people, and was so entertaining that he spent his evenings “cheerfully and profitably.”

One evening, however, when he was “attacked in a most ungenerous and cowardly way in the streets, he resented the indignities put upon him in a very summary manner, by fairly knocking several of the party down . . . It is due to poor John to state that upon this occasion he behaved for a long time with great forbearance. But upon being struck, he was roused to exert his strength, which was prodigious.”

In January 1819, Sakeouse was delighted to learn that the Admiralty wished him to accompany Edward Parry on another two-ship expedition to the Arctic. He eagerly anticipated sailing into Lancaster Sound when, without warning, according to the Penny Magazine, he “was seized with an inflammatory complaint.” The finest doctors in Edinburgh attended him and, after a few days, he seemed to recover. But as “he began to gain strength, he by no means liked the discipline to which he was subjected, and the prescribed regimen still more displeased him.” Sakeouse suffered a relapse, and on Sunday evening, February 14, 1819, at the age of twenty-one or twenty-two, he died.

Many of Edinburgh’s leading lights attended his funeral, and several luminaries journeyed north from London. People remembered Sakeouse as gentle, modest and obliging, and noted that he appreciated any kindness extended to him. “In a snowy day, last winter,” according to Blackwood’s Magazine, “he met two children at some distance from Leith, and observing them to be suffering from the cold, he took off his jacket, and having carefully wrapped them in it, brought them safely home. He would take no reward, and seemed to be quite unconscious that he had done anything remarkable.” In May 1819, when Edward Parry sailed again for the Arctic, he bitterly regretted the absence of John Sakeouse.