7.

Edward Parry Identifies a Northern Channel

Because he did not believe in the existence of the Croker Mountains, John Barrow, the Admiralty mastermind, decided to double-down—to dispatch not one but two expeditions to investigate the Northwest Passage. Both would become legendary, though for dramatically different reasons. The lesser, an overland expedition, would be led by John Franklin (see the next chapter).

William Edward Parry would lead the more important. Recently turned twenty-eight, and newly appointed to the rank of lieutenant commander, Parry received orders to sail directly to Lancaster Sound, in which John Ross had apparently sighted the disputed mountains. Early in May of 1819, less than six months after he returned from that voyage, Parry set out from London with two former bomb-ships, the 352-ton Hecla and the 180-ton Griper. They carried complements, respectively, of fifty-seven and thirty-seven men.

At Davis Strait, instead of taking the whaling route northward along the west coast of Greenland before swinging west, as John Ross had done, Parry challenged the Middle Ice—a generally impassable array of massive icebergs and lethal bergy bits between Greenland and Baffin Island. Whalers avoided it. Parry’s risky manoeuvre could save time, but meant butting through the ice. This time out he was lucky. By the end of July, having survived several close calls, he reached the entrance to Lancaster Sound. Had he been correct in repudiating Ross? An “oppressive anxiety . . . was visible in every countenance,” he wrote later, “while, as the breeze increased to a fresh gale, we ran quickly to the westward.”

At 6:00 p.m. on August 2, 1819, while noting a long swell “rolling in from the southward and eastward,” Parry wrote, “land was reported to be seen ahead. The vexation and anxiety produced on every countenance by such a report was but too visible.” On drawing nearer, however, this “was found to be only an island, of no very large extent, and that, on each side of it, the horizon still appeared clear for several points of the compass.”

In 1819, William Edward Parry led one of the most successful of all Arctic voyages.

Directly ahead, as far as the eye could see, lay an open channel 130 kilometres wide. The Croker Mountains did not exist. Vindicated, jubilant and relishing the cheers of his companions, Edward Parry sailed onwards. On August 6, he came upon a broad channel, at least fifty kilometres wide, that opened to the south. Thinking this might lead to a coastal waterway, Parry sailed into Prince Regent Inlet, as he named it, for about two hundred kilometres. But then, encountering ice, he turned around and, back at Lancaster Sound, resumed sailing westward through the broad channel that, from this inlet onwards, he called Barrow Strait.

On September 4, after sailing through heavy weather, and also past a notable waterway leading north, “Wellington Channel,” Parry reached 110° west longitude. After Sunday prayers, he told his men that, having achieved the first objective set by the Board of Longitude, they had won £5,000 (£1,000 for him as captain and the rest to be distributed among his men). The next day, at Melville Island, the two ships dropped anchor for the first time. The men raised the Union Jack. Over the next several days, they spent time on shore, found coal for burning, and hunted and bagged a great many succulent ptarmigan.

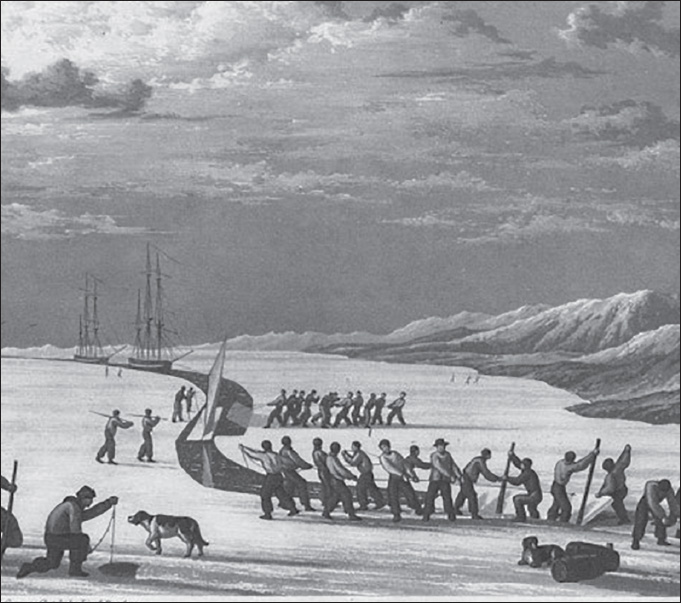

Crewmen work HMS Hecla and Griper into Winter Harbour in 1819. This engraving is based on a sketch by Parry’s Lieutenant Frederick William Beechey, who visited Beechey Island during this voyage and named it after his father, artist William Beechey.

With temperatures falling and the days growing shorter, Parry beat farther west. On September 17, at nearly 113°, he met impenetrable ice at what would later be named McClure Strait. He retreated to a cove he had spotted on Melville Island. As ice formed around the two ships, Parry managed to warp them, or haul them by using a line attached to a fixed anchor, into a safe spot at a place he called Winter Harbour. He wrote of feeling exhilarated, and why not? His voyage was already an unprecedented success. He had charted more than 1,600 kilometres of coastline and discovered a waterway that, measured from Greenland, extended roughly halfway to the Icy Cape that, four decades before, Captain James Cook had reached from the west.

Now came a second great challenge: wintering in the High Arctic. For this, Parry had prepared. As cold and twenty-four-hour darkness gripped the expedition, he engaged his men with literacy classes and theatrical entertainments. Geophysicist Edward Sabine, the thirty-one-year-old Royal Artillery captain, set up a magnetic observatory 650 metres from the ships—far enough that the iron in the vessels would not interfere with his readings.

Sabine had sailed on the Croker Mountain expedition with Ross, and later recalled his “mortification at having come away from a place which I considered as the most interesting in the world for magnetic observations, and where my expectations had been raised to the highest pitch, without having had an opportunity of making them.” Now, when he wasn’t taking readings, Sabine edited a newspaper filled with jokes and shipboard shenanigans.

Midshipman James Clark Ross, still just nineteen, emerged as the most popular actor in the Royal Arctic Theatre, and proved sporting enough to take on many female roles. Early in June, Edward Parry took a dozen men and spent two weeks hauling a handcart filled with supplies along the coast of Melville Island. Then came a six-week struggle to free the ships from the surrounding ice.

Finally, on August 1, the vessels escaped into open water. Parry again steered west. At the southwestern tip of Melville Island, just beyond 113°, he sailed up near a wall of multi-year ice that stood thirteen to sixteen metres (fifty feet) high. Recognizing an impenetrable barrier when he saw one, Parry turned around and sailed for home.

Early in November, having completed one of the most successful Arctic sailing expeditions of all time, Edward Parry arrived in London to a hero’s welcome. Overnight, he became the most celebrated man in England. He was promoted to commander and, in his hometown of Bath, he received the keys to the city. In his journal, he wrote that he was confident that the western outlet of the Passage would be found at Bering Strait.

But that wall of ice at 113° had made an impression. Parry doubted now that anyone would be able to reach Bering Strait through Lancaster Sound. Wondering about the thoroughness and efficiency of earlier explorers, he turned his attention to Hudson Bay. Perhaps a channel swung north before it reached those areas traversed by Hearne and Mackenzie? He identified Cumberland Sound, Sir Thomas Rowe’s Welcome and Repulse Bay as “the points most worthy of attention.” And he added that “one, or perhaps each of them, may afford a practicable passage into the Polar Sea.”

Parry wanted to lead an expedition into those reaches, where “there certainly does seem more than an equal chance of finding the desired passage.” But he also realized, as he told his family, that “the success we met with is to be attributed under Providence to the concurrence of many very favorable circumstances.” In his journal he went further still, tempering his earlier optimism and cautioning against “entertaining too sanguine a hope of finding such a [northwest] passage, the existence of which is still nearly as uncertain as it was two hundred years ago, and which possibly may not exist at all.”