8.

The Yellowknife Rescue John Franklin

The Inuit hamlet of Kugluktuk, formerly known as Coppermine, is located at the mouth of the Coppermine River, where it empties into the Arctic Ocean. From a ridge at the edge of town, you can gaze across the river and see the bluff where, on July 17, 1771, at latitude 67°8´25˝ north, Samuel Hearne stood looking out when he became the first explorer to reach this northern coast of North America. Fifty years later almost to the day, on July 18, 1821, having followed Hearne’s route to this location, John Franklin of the Royal Navy established a campsite at that vantage point.

A few kilometres upriver, he had taken unhappy leave of Akaitcho, an eminent Yellowknife-Dene who had warned him against continuing his journey this late in the year. A fearsome leader of about 190 people, and a man who had lived all of his thirty-five years in this part of the world, Akaitcho told Franklin that if he now set out eastward along the coast, he would never return alive. The naval officer proved impervious to advice. He said goodbye to Akaitcho and his hunters and proceeded to this location with twenty men. He would follow his Royal Navy orders to the letter.

Lieutenant John Franklin had left England on May 23, 1819, eleven days after Edward Parry embarked on his epochal voyage. He was ordered to explore the Arctic coast of North America from the mouth of the Coppermine eastward to Hudson Bay. The hope was that, in tandem with Parry’s voyage, this two-pronged exploration might locate the Northwest Passage. In Sir John Franklin’s Journals and Correspondence: The First Arctic Land Expedition, editor Richard C. Davis notes that a growing interest in geomagnetism and the shifting magnetic poles provided a second motivation.

From this campsite at the mouth of the Coppermine River, ignoring warnings from Yellowknife guides who knew the area, John Franklin set out eastward along the Arctic coast. George Back, one of two artists on the expedition, painted this view.

The Admiralty’s John Barrow, increasingly aware of the unreliability of compass readings near the north magnetic pole, surmised that Samuel Hearne might have been wrong about the latitude he had reached. To ascertain the position and direction of the coastline eastward from that location, he wanted “an officer well skilled in astronomical and geographical science, and in the use of instruments.”

Franklin had shown some aptitude. Officially appointed in April, he departed one month later with five fellow Royal Navy men. In a biography of George Back, one of two junior officers (midshipmen) who joined the expedition, Peter Steele writes that the deeply religious Franklin “was plump, unfit and unused to hard exercise, with no experience of travelling on foot, or running rivers in canoes, or hunting for food—as neither did any of his chosen officers.” No competent contemporary traveller, he adds, “would contemplate allowing less than a year to embark on such a major journey, even over already known and mapped country.”

Together with some Selkirk settlers bound for Red River Settlement, Franklin sailed on a Hudson’s Bay Company ship, the Prince of Wales, with instructions to make his way from Coppermine to Hudson Bay while keeping detailed meteorological and magnetic records. The Admiralty, with no experience mounting overland expeditions, and no appreciation of the challenges involved, proposed to draw logistical support from the two fur-trading companies active in Rupert’s Land.

In London, representatives of the HBC and the North West Company agreed to assist Franklin in every way possible. But in the North Country, their rivalry was spiralling into a murderous crescendo. Each company accused the other of ambushing and killing agents. This poisonous situation would make cooperation difficult at best. And on August 30, 1819, when Franklin arrived at York Factory, headquarters of the HBC, he discovered that three North West Company partners were being detained there—hardly a good omen.

Franklin spent twenty-three months making his way 4,090 kilometres northwest from York Factory on Hudson Bay to the mouth of the Coppermine at the edge of the Arctic Ocean. He faced one obstacle after another. Initially, the HBC could spare only one traditional York boat and a single man, so he had to leave much of his gear for later forwarding. The explorer Alexander Mackenzie had responded to a pre-departure request for information by observing that Franklin should not expect, in his first season, to get beyond Île-àla-Crosse—wise words.

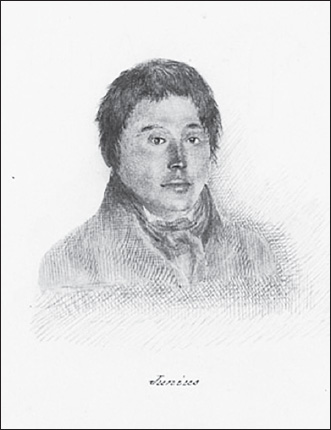

This is probably the earliest likeness of John Franklin. It is based on a painting by William Derby, born the same year as Franklin (1786), and illustrates an article by L. T. Burwash in the Canadian Geographical Journal of November 1930.

A newcomer to Red River Settlement, on the other hand, had written recommending bacon as a primary meat source. Words not so wise. As yet unfamiliar with pemmican, the light-weight, dried-meat staple of the voyageur diet, much less with hunting buffalo and caribou, Franklin had brought seven hundred pounds of salted pig, which on arrival was already mouldy and inedible.

The hefty lieutenant did not take naturally to rough-country trekking. On the Hayes River at Robinson Falls, according to George Back, Franklin was walking along a rocky bluff when he slipped on some moss “and notwithstanding his attempts to stop himself, went into the stream.” He landed in deep water ninety metres downstream, “and after many fruitless trials to get a landing, he was fortunately saved by one of the boats, which by dint of chance was near the spot.”

With the occasional help of HBC men travelling in the same direction, Franklin and his men transported a huge weight of supplies and instruments along rough trails and over portages. They travelled 1,130 kilometres up the Nelson and Saskatchewan Rivers to Cumberland House, arriving late in October. Franklin sent one able seaman home because, assigned to carry supplies with the voyageurs and four tough Orcadian Scots, he had been unable to maintain the pace.

Franklin stayed a couple of months at Cumberland House, some 685 kilometres short of Île-à-la-Crosse. Then, starting in mid-January 1820, with George Back, a single seaman (John Hepburn) and some Indian guides, Franklin spent another two months trekking north on snowshoes. He made his way to Fort Chipewyan on Lake Athabasca, with a view to organizing the next leg of the trip. He arrived on March 26, having covered 1,380 kilometres in sixty-seven days.

This travel rate, about twenty-one kilometres per day, would have drawn derisive laughter from expert snowshoers, who regularly travelled at three times that speed. George Back, age twenty-two, wrote in a letter to his brother that the journey highlighted “a wide difference between Franklin and me . . . he had never been accustomed to any vigorous exertion; besides, his frame is bulky without activity.”

Even so, George Simpson, now emerging as a fur-trade impresario, exaggerated when he disparaged Franklin: “He must have three meals per diem. Tea is indispensable, and with the utmost exertion, he cannot walk above Eight miles in one day.” By the time Simpson wrote that, the two men had exchanged acerbic letters, with the HBC governor challenging Franklin’s Royal Navy assumption that the fur trade existed primarily to serve his expedition.

After Franklin left Cumberland House, two naval men remained there to transport anticipated supplies. But shortages throughout the North Country meant they arrived at Fort Chipewyan with ten bags of rotting pemmican. The party spent eleven days canoeing north to Fort Providence on Great Slave Lake.

Akaitcho grew impatient with the expedition’s “slow mode of travelling.” Artist Robert Hood, rival to George Back in many ways, drew this likeness of the Yellowknife leader.

Here Franklin met Willard Ferdinand Wentzel. This North West Company veteran had been hired to recruit guides, hunters and interpreters from among the Yellowknife or “Copper Indians,” and to accompany the expedition to the coast. Here, too, on July 30, 1820, Franklin met Akaitcho, from whom, the following July, he would part angrily near the mouth of the Coppermine. Akaitcho was known as a man “of great penetration and shrewdness,” Franklin wrote now, and his older brother, Keskarrah, had travelled with Matonabbee. Akaitcho’s immediate followers included forty warriors (men and boys) known for their ferocity. For the past decade, while working as hunters out of Fort Providence, Akaitcho and his men had ravaged nearby tribes of Dogrib and Hare Indians, stealing furs and women with impunity.

At their first meeting in the wilderness, to assert British superiority, Franklin and his officers donned full-dress uniforms, complete with medals, and placed a silk Union Jack atop their tent. Akaitcho was not impressed. Accompanied by two lieutenants, the Yellowknife leader arrived wearing a blanket over a white cloak. He smoked a peace pipe, downed some spirits and informed the visitors that they would not be travelling much farther this season.

Franklin said that he hoped to reach the Arctic coast, and that he was bent on discovering a northwest passage that would accommodate sailing ships. He promised that if Akaitcho and the Yellowknife would accompany his expedition as guides and hunters, he would give them cloth, ammunition, tobacco and iron tools, and also settle their outstanding debts with the North West Company. Akaitcho agreed, though he warned that, because of the history of hostilities, he would not enter Inuit-controlled territory.

After setting out from Fort Providence, Akaitcho reiterated that the expedition could not even try to approach the Arctic coast this season. He had not realized, he explained, that Franklin and his men would adopt such a “slow mode of travelling.”

The native leader and his men pressed on ahead, and waited for Franklin 320 kilometres farther north, at Winter Lake. While they were catching up, according to Back, “a mutinous spirit displayed itself amongst the men. They refused to carry the goods any farther, alleging a scarcity of provisions as the reason for their conduct.” In truth, they weren’t eating nearly enough. Franklin responded by observing they were “too far removed from justice to treat them as they merited. But if such a thing occurred again, he would not hesitate to make an example of the first person who should come forward by ‘blowing out his brains.’”

This speech had the desired effect, though the overworked voyageurs would later reiterate their distress with increasing urgency. At Winter Lake, roughly halfway to the coast from present-day Yellowknife, Franklin’s men built Fort Enterprise. The expedition now comprised six Europeans, including Wentzel, and also two Métis interpreters and seventeen voyageurs, plus three wives and three children.

The four Orcadian Scots, who had studied the fine print before signing on in Stromness, had exercised an option clause at Fort Chipewyan, and turned around and headed for home. Franklin noted that they had “minutely scanned our intentions, weighed every circumstance, looked narrowly into the plan of our route, and still more circumspectly to the prospect of return.”

At Fort Enterprise, Akaitcho again warned Franklin against descending the Coppermine with winter approaching: “I will go in spring, but not now, for it is certain destruction. But if you are determined to go and die, some of my young men shall also go [to the coast] because it shall not be said that you were abandoned by your hunters.” As for proceeding along the coast for any distance, he declared that madness. Finally, Akaitcho convinced Franklin to settle for a couple of scouting forays to the headwaters of the Coppermine River—difficult sorties that vindicated his opinion.

Back at Enterprise, where Wentzel had supervised the building of three log houses, the two midshipmen, George Back and Robert Hood, got into a jealous competition over a young Yellowknife woman they called Greenstockings. John Hepburn prevented a duel by surreptitiously removing ammunition from their guns. Franklin decided this was a good time to separate the two young men. With game proving scarce, and the party running low on ammunition, he sent the rugged George Back to Fort Chipewyan for supplies, a snowshoe journey of 885 kilometres.

Along the way, the plain-speaking Back berated fur-trade managers to see that expedition goods sent from York Factory were brought forward. He, too, traded sharp letters with George Simpson, who noted in his journal that Back had visited him at Fort Wedderburn, not far from Fort Chipewyan. “From his remarks I infer,” Simpson wrote, “there is little probability of the objects of the expedition being accomplished . . . It appears to me that the mission was projected and entered into without mature consideration and the necessary previous arrangements totally neglected.”

Early in the winter of 1821, two Inuit interpreters arrived at Fort Enterprise from York Factory: Tattannoeuck and Hoeootoerock. Among the English, they were known respectively as Augustus and Junius. Tattannoeuck would one day play a crucial role in keeping Franklin alive. Born in the late 1700s, and raised in a settlement over three hundred kilometres north of Fort Churchill, he had by now worked as a Hudson’s Bay Company interpreter for four years. In 1820, having married and begun a family, he had signed on to travel with this overland expedition. Tattannoeuck was a proud man, according to editor C. Stuart Houston, “who asked from the voyageurs the same deference and respect that they showed the officers.”

Pierre St. Germain, the “mixed-blood” hunter and interpreter who had fetched the two Inuit, interviewed some of Akaitcho’s followers and learned of the dangers the expedition would face at the coast. Franklin got wind of this and threatened to take St. Germain to England and put him on trial. The voyageur replied, all too presciently, that he didn’t care where he lost his life, “whether in England or accompanying you to the sea, for the whole party will perish.”

On June 14, 1821, after an endless winter, the expedition—together with a number of Yellowknife hunters—set out for the headwaters of the Coppermine River. The men hauled sledges over rough and melting ice until early July. Then they took to the Yellowknife River, though shallows and rapids necessitated frequent portages. By July 12, with the hunters having only sporadic luck, the expedition retained enough food for fourteen days at what Franklin would describe as “the ordinary allowance of three pounds of meat to each man per day.” The fur-trade standard, as noted elsewhere by John Richardson, Franklin’s second-in-command, was in fact eight pounds of fresh meat per day. Not surprisingly, the voyageurs complained of hunger and exhaustion.

As the large party made its way down the Coppermine, Franklin sent Tattannoeuck ahead. The Inuk knew full well that at Bloody Falls, fifty years before, explorer Samuel Hearne had seen a great number of Chipewyan-Dene massacre two dozen Inuit. Accompanied by Hoeootoerock, he approached those rapids with caution. The two newcomers began making friends with the people they met. But when the locals saw Franklin approaching with a great many Yellowknife, they feared another massacre and melted into the surrounding countryside, never to be seen again.

One old man, Terreganoeuck, had been unable to flee. He assured Franklin through Tattannoeuck that he would find a few Inuit to the east—a suggestion that discounted any advance warnings from those who had fled, and which probably encouraged Franklin to forge ahead when he had no business doing so.

The expedition spent a few days camped at Bloody Falls, where a scattering of whitened skulls testified to the truth of Samuel Hearne’s journal. As John Richardson put it, “The ground is still strewed with human skulls and as it is overgrown with rank grass, appears to be avoided as a place of encampment.” George Back wrote: “The havoc that was there made was but too clearly verified—from the fractured skulls—and whitened bones of those poor sufferers—which yet remained visible.” He later produced a painting that makes plain what he witnessed.

At the mouth of the Coppermine River, on July 18, 1821, Franklin established a camp on the eastern bluff overlooking the river. Coronation Gulf lay to the north, sprinkled with round islands, just as Samuel Hearne had reported. Like that earlier traveller, John Richardson noted the presence of many seals, and added: “The islands are high and numerous and shut the horizon in, on many points of the compass.” Franklin took a series of observations and corrected Hearne’s latitude. That first explorer had placed this location too far north.

For days, Akaitcho had been warning Franklin that the expedition did not have enough food to proceed. Animals were scarce, winter was approaching and his hunters would go no farther. Some of his men had already defected. To proceed along the coast would mean risking death. In this, not his first warning, but his first concerted effort to save the expedition, he urged Franklin to retreat to Fort Enterprise.

Now, despite these warnings from Akaitcho and his men, and also from his most experienced voyageurs, Pierre St. Germain and Jean Baptiste Adam, John Franklin made a decision that would cost the lives of more than half his men. Dismissing all protests and objections, he insisted on adhering precisely to his original instructions as written in England. Eleven of the twenty men he led eastward would perish. But here is the most revealing statistic: four of the five Royal Navy men would survive, as opposed to only five of the fifteen voyageurs and interpreters.

Again: of the twenty men who followed Franklin beyond the mouth of the Coppermine, ten voyageurs and one Englishman would die. The British public, on reading about this discrepancy in the death rate, would hail it as a demonstration that Royal Navy men were tough, tenacious and resourceful. Later, Canadian analysts would advance an alternative interpretation, suggesting that Franklin coddled his fellow Britishers, allowing them to conserve their energies, while driving the voyageurs to do all the heavy, debilitating work.

Now, in 1821, John Franklin dismissed Akaitcho’s concerns as groundless. He did not care what the fellow said. A British naval officer, he had his orders and he would follow them. His career depended on it. In his view, the voyageurs lacked British grit, courage and Christian faith. Surely the expedition would encounter Inuit hunters eager to assist. Franklin was a British naval officer. In a pinch, the Lord would provide.

The hubris of John Franklin was more cultural than personal. According to C. Stuart Houston, “Back’s journal allows us to make a better assessment of the rigidity and stubbornness of Franklin, a product of the old British ‘do or die’ school who drove his men far too hard.” Fellow Canadian scholar Richard C. Davis, editor of Franklin’s journal, suggests that the lieutenant suffered from “a well-intentioned narrowness of vision that was systemic to his dominant culture, and that crippled Franklin when he found his culture dependent on others.”

The ethnocentric arrogance of imperial Britain, Davis writes, “made it virtually impossible for Franklin to respect the traditionally-evolved wisdom of Yellowknife Indians and Canadian voyageurs, even though their assistance was crucial to the success of the expedition.” What today we regard as insensitive, arrogant and overbearing “was viewed as the epitome of civilized enlightenment by all those who basked in its nineteenth-century glow.”

The looming debacle derived partly from the Admiralty’s lack of preparedness (how difficult could an overland expedition be?) and partly from supply shortages linked to the spiralling fur-trade rivalry. But as Davis notes, the expedition “could have reached a far happier conclusion had Franklin been less a man of his times.”

The naval man told Akaitcho that nothing would stop him from making his way east along the coast. He would travel to Repulse Bay, or perhaps even to Hudson Bay. The Yellowknife leader said he doubted he would see Franklin again. But he agreed to cache some supplies at Fort Enterprise, just in case. Wentzel, the veteran fur trader, having fulfilled his contract, knew better than to linger. He returned south with the last few Yellowknife hunters. And, to reduce the size of the expedition, Franklin released four voyageurs to go with him.

The Métis interpreters, Pierre St. Germain and Jean Baptiste Adam, wanted to leave as well. They were rightly worried about starving to death, since the party had food enough for perhaps three weeks and only a thousand balls of ammunition. St. Germain noted that, with the departure of the Yellowknife, their interpretive services would no longer be required. But Franklin refused to release the two. Of those nineteen men who would remain with him, these were the two best hunters. They had signed a contract. He set a watch on them, so that, when the last Yellowknife departed, they did not slip away.

Nor did the other voyageurs wish to continue. During the portages from Fort Enterprise, they had frequently carried packs weighing 180 pounds through melting lake water, which had caused their feet and legs to swell. The Royal Navy officers, meanwhile, as Franklin would later observe, had carried “such a portion of their own things as their strength would permit.”

As a group, the voyageurs again complained of hunger, swollen limbs and exhaustion. They warned that the two large birch-bark canoes they had hauled to this Arctic coast were designed for river travel, not for the rough waters and ice floes they would encounter along the coast. “They were terrified,” Franklin later wrote, “at the idea of a voyage through an icy sea in bark canoes.” Their fears would prove well-founded.

On July 21, 1821, three days after reaching the mouth of the Coppermine, Franklin set out eastward with nineteen men in two birch-bark canoes. Poling around ice floes and huddling on shore through gale-force winds, he and his men fought their way along the northern coast of the continent for 885 kilometres. They mapped Coronation Gulf, Bathurst Inlet and Kent Peninsula. Franklin wondered what lay farther east.

But on August 15, after weeks of slogging, with the canoes battered and broken, supplies running dangerously low and additional Inuit hunters notable only for their absence, he realized he could go no farther. George Back enumerated six reasons for turning around: “The want of food—the badness of the canoes—the advanced state of the season—the impossibility of succeeding [in reaching] Hudson Bay—the long journey we must go through the barren lands and . . . the dissatisfaction of the men.”

On Kent Peninsula, Franklin planted the Union Jack on a hill. He named the location Point Turnagain. Then, having delayed for five days after supposedly making his decision, hoping always for the divinely inspired arrival of Inuit hunters, he gave the order to retreat to Fort Enterprise. Instead of tracing the coastline of Bathurst Inlet, as they had done during their advance, the men sought to save time by cutting straight across open water. The rough seas almost swamped the canoes. On reaching the far shore, instead of paddling west to the mouth of the Coppermine, Franklin and his men started tracking up the Hood River, which looked to be a shortcut. It was not.

While the voyageurs stumbled on, lugging ninety pounds each, including ammunition, hatchets, ice chisels, astronomical instruments, kettles, canoes and Bibles, the officers carried little. By September 4, the men had consumed the last of the pemmican. They were still more than six hundred kilometres from Fort Enterprise. They shot and shared the occasional partridge, and also a few muskox. They scoured the carcasses of caribou killed by wolves. And they choked down bitter lichen they cut from rocks, tripe de roche, which gave them diarrhea. Now winter weather arrived, as promised, bringing blizzards that forced the men to shelter in their tents.

“There was no tripe de roche,” Franklin would write, “so we drank swamp tea and ate some of our shoes for supper.” These shoes were leather moccasins from which the men could suck sustenance. They were starving. At one point, after standing up suddenly, Franklin fainted. One of the voyageurs, the interpreter Pierre St. Germain, gave each of the naval officers a small piece of meat he had saved from his allowance. This act “of self-denial and kindness,” Franklin wrote later, “being totally unexpected in a Canadian voyageur, filled our eyes with tears.” Unfortunately, in his narrative, judging from the more trustworthy journal of John Richardson, Franklin attributed the gesture to the wrong man.

Travelling grew more dangerous. While scrambling upwards on slippery rocks, the heavily loaded men fell often. They were suffering from both exhaustion and hypothermia, and George Back noted that “we became so stupid that we stumbled at almost every step.” Then a canoe overturned and dumped Franklin into fast-rushing water. He lost a box containing his journals and meteorological observations, leaving him dependent on the writings of Richardson and Back, which he would commandeer for his final report.

Not surprisingly, the voyageurs began again to rebel. According to Back, who was the only Englishman able to speak French, “the Canadians talked seriously of starvation and became proportionally dispirited—and not without cause, for we had neither seen tracks of deer nor marks of Indians during the day.” In their weakened state, the men could no longer carry the heavy loads. They jettisoned the fishing nets. They refused to share partridges they had secretly shot. Then, in an act of folly, one of them dropped the sole remaining canoe and saw it smash onto the rocks.

Franklin declared it beyond his power to describe the anguish he felt on hearing this news. The Hood River led to the Coppermine, which had to be crossed. John Richardson volunteered to swim to the other side with a line, but the water was so cold that his arms turned to lead and the voyageurs had to haul him back to shore. Finally, despite a scarcity of materials, St. Germain managed to improvise a makeshift raft that enabled the men to paddle across one by one. This operation, at a spot Franklin named Obstruction Rapids, wasted eight days.

Richardson had cut his foot and walked with a limp. The hefty Franklin had been reduced “almost to skin and bones.” And midshipman Robert Hood, the frailest of the navy men, was reduced to crawling through snowdrifts on his hands and knees. Things had been terrible for some time. Now they grew desperate. Hoeootoerock disappeared while hunting, and Tattannoeuck searched but failed to find him. Franklin sent George Back and four voyageurs to dash forward for help. Perhaps at Fort Enterprise they would find food, and someone could return with some of it.

During the desperate return flight to Fort Enterprise, Hoeootoerock (Junius) went hunting and never came back. Portrait by Robert Hood.

Robert Hood could go no farther. He pleaded to be left alone. Richardson and Hepburn insisted on staying to care for him. Franklin left the two Scots with Hood and pushed on with nine voyageurs. But the next day, four of these, including a muscular Iroquois named Michel, pleaded that they could not continue. Franklin allowed them to return to the three British sailors. He pushed on with five voyageurs through heavy winds and drifting snow. When at last, having slogged more than sixty kilometres in five days, he and his men stumbled into Fort Enterprise, they found it empty. Where were the promised supplies? “It would be impossible to describe our sensations after entering this miserable abode,” Franklin wrote later, “and discovering how we had been neglected. The whole party shed tears.”

George Back had left a note. With his four men, he had gone to seek help from Akaitcho, who had said he would winter in one of his camps south of Fort Enterprise. Franklin and his comrades, who soon determined they were too weak to go anywhere, huddled together for warmth as the temperature fell to almost thirty degrees below zero Celsius. They used chairs and floorboards to build a feeble fire. They pulled down deerskin curtains and chewed them for sustenance. They were starving to death and knew it.

Incredibly, after suffering through eighteen days, they heard footsteps and voices. Akaitcho? Had rescue arrived? No. John Richardson and John Hepburn stumbled into the room. They were the only two survivors from the invalid camp. And they had a terrible story to tell. Michel, the Iroquois voyageur, had reached them alone. He said that his companions had starved to death en route. To Hood, Richardson and Hepburn, he distributed meat, saying he had shot a hare and a partridge. “How I shall love this man,” Hepburn had said, wolfing down the strange-tasting meat, “if I find that he does not tell lies like the others.”

Michel began behaving strangely. To go hunting, in addition to his usual knife, he carried a hatchet—as if, Richardson thought, he meant to hack away at “something he knew to be frozen.” The hunter produced slices of meat that came, he said, from a wolf he had killed with a caribou horn. Richardson began to suspect that Michel was butchering one or more of his dead companions. Half to himself, Michel muttered about how white men had murdered and eaten three of his relatives. Always one of the strongest voyageurs, he seemed now to grow stronger. When Richardson urged him to hunt, he answered: “It is no use hunting, there are no animals. You had better kill me and eat me.”

Next morning, Richardson and Hepburn went looking for kindling. From the tent, they heard voices: Michel arguing with Robert Hood. Then came a shot. Rushing back to camp, they found Hood slumped over dead, with a book at his feet: Bickersteth’s Scripture Help. He had accidentally shot himself, Michel said, while cleaning a gun. But when Richardson, a doctor, examined the body, he “discovered that the shot had entered the back part of the head, and passed out at the forehead, and that the muzzle of the gun had been applied so close as to set fire to the night-cap behind.”

Richardson accused the voyageur of killing Hood. Michel adamantly denied it. But then he stayed close to camp, never allowing the two Scots to be alone for a moment. Richardson conducted a brief funeral service, and on October 23, the party set out for Fort Enterprise. When Michel left a campsite, ostensibly to collect tripe de roche, but probably to prime his rifle, the two Scots conferred. In a direct confrontation, they would be no match for Michel, who carried a rifle, two pistols, a bayonet and a knife. Hepburn volunteered to do the necessary. Richardson said no, he would take responsibility. He ducked down into some bushes. When Michel came back, carrying no tripe de roche but just a loaded gun, Richardson stepped out and shot him through the head.

The two Scots stumbled on to Fort Enterprise, where on October 29 they joined their fellows in starvation and prayer. Richardson wrote that language could not “convey a just idea of the wretchedness of the abode.” The house had been torn apart for firewood, and the windows stood open to the cold except for a few loose boards. Only one man was still able to fetch firewood. Another lay immobile on the floor. “The hollow and sepulchral sound of their voices,” Richardson wrote, “produced nearly as great horror in us as our emaciated appearance did on them, and I could not help requesting them more than once to assume a more cheerful tone.”

Soon after he and Hepburn arrived, two voyageurs died of starvation. The survivors had barely enough strength to drag their bodies to the far side of the room. When one man fell to sobbing uncontrollably, Franklin read to him from the Bible. Then he became too weak to hold the Bible upright, and he and Richardson, reciting from memory, repeated verses from Psalm 23: “The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want. He maketh me to lie down in green pastures . . .”

Later, Franklin wrote that he noticed a weakening not just in the men’s bodies but in their mental faculties. “Each of us thought the other weaker in intellect than himself, and more in need of advice and assistance. So trifling a circumstance as a change of place, recommended by one as being warmer and more comfortable, and refused by the other from a dread of motion, frequently called forth fretful expressions . . .”

Franklin had reached Fort Enterprise on October 11. By November, he and his fellows were surviving on a refuse heap of sleeping robes and bones that had been left behind as garbage. But then, on November 7, three Yellowknife Indians arrived, bringing deer meat and tongues. They had travelled ninety kilometres in two and a half days. George Back, desperately searching here and there, had finally located the winter camp. Akaitcho had sent two of his best hunters with supplies. Now, these two tough Yellowknife men were shocked by what they saw at Fort Enterprise. According to Richardson, they “wept on beholding the deplorable condition to which we had been reduced.”

The Yellowknife set about nursing Franklin and his fellows back to life. Richardson wrote, “The ease with which these two kind creatures separated the logs of the store-house, carried them in, and made a fire, was a matter of the utmost astonishment to us . . . We could scarcely by any effort of reasoning, efface from our minds the idea that they possessed a supernatural degree of strength.”

When the survivors were well enough, they set out slowly on snowshoes for Akaitcho’s camp. “Our feelings on quitting the fort,” Franklin wrote, “may be more easily conceived than described.” Of the twenty men who had set out along the coast, nine survived, including Franklin. Now, encountering deep snow, the Yellowknife hunters lent their snowshoes to the invalids. Richardson wrote of being treated with the “utmost tenderness,” and added that the Yellowknife “prepared our encampment, cooked for us and fed us as if we had been children; evincing humanity that would have done honour to the most civilized nation.”

At the winter campsite of the Yellowknife, the fearsome Akaitcho insisted on preparing a meal for the survivors with his own hands—a remarkable gesture for a warrior leader. He had not been able to cache food at Fort Enterprise because his own people were going hungry. Three of his best hunters, close relatives, had drowned when their canoe capsized in Marten Lake. Their families, grief-stricken, had thrown away their clothes and destroyed their guns. As a result, the remaining men had killed fewer animals than might have been expected. This had worsened the prevailing shortage.

Even so, when Akaitcho learned that Franklin would be unable to repay him all that had been promised, he took it with good grace. In an oft-quoted paraphrase, he added: “The world goes badly. All are poor. You are poor. The traders appear to be poor. I and my party are likewise, and since the goods have not come in we cannot have them. I do not regret having supplied you with provisions, for a Yellowknife can never permit white men to suffer from want in his lands without flying to their aid.”

Akaitcho accompanied the expedition southward, teaching the party, and notably the fair-skinned Franklin, how to treat frostbite by rubbing any telltale white patches that appeared on their faces. At parting from the Yellowknife, Richardson wrote, “We felt a deep sense of humiliation at being compelled to quit men capable of such liberal sentiments and humane feelings in the beggarly manner in which we did.”

By the time Franklin reached England in October of 1822, the British public had already got wind of his Arctic ordeal. The Admiralty promoted him to post captain. Celebrated as “the man who ate his boots,” he became a fellow of the prestigious Royal Society. When he published his Narrative of a Journey to the Polar Sea, drawing heavily on the journals of John Richardson, discerning readers labelled it ponderous—though it became an immediate bestseller.

Of the eleven men who had died, only one was British. Ten were “mixed-blood” Indians or French-Canadian voyageurs. Franklin’s countrymen viewed this as confirming their own moral and constitutional superiority—their ability to meet and overcome adversity. Franklin himself became a symbol of the cultural supremacy of the British Empire.

Far from London, experienced observers saw things differently. They began developing a counter-narrative. The voyageurs died in such numbers because they were worn down by the unequal division of labour. They were the ones who hauled and repaired the canoes. They were the ones who did the hunting, the ones who trekked great distances while carrying packs weighing anywhere from 90 to 180 pounds. They did these things without enough food. No surprise, they grew weak. No wonder they died.