9.

Tattannoeuck Prevents a Second Debacle

Having narrowly survived his first overland expedition thanks to Akaitcho, John Franklin returned from his second thanks only to a forgotten Inuk from the northern reaches of Hudson Bay. On that first expedition, as we have seen, Franklin lost more than half his men to exposure or starvation. During the desperate return to Fort Enterprise, Tattannoeuck had pushed on ahead of the struggling party, searching still for his friend Hoeootoerock, but got lost. When finally he stumbled into Fort Enterprise, Franklin was thrilled, and noted that “his having found his way through a . . . country he had never been in before, must be considered a remarkable proof of sagacity.”

Afterwards, Tattannoeuck returned to Fort Churchill, worked again for the HBC and then for a missionary, John West, who converted him to Christianity. In the Canadian Dictionary of Biography, Susan Rowley neatly summarizes this period. In the spring of 1824, this time with another friend, Ouligbuck, Tattannoeuck agreed to join Franklin on a second expedition.

Back in England, buoyed by the fact that his countrymen judged his first misadventure a signal success, John Franklin set about preparing a second overland sortie. And here he gave the lie to those who say British naval officers were incapable of learning from experience. Soon after he arrived home, acting with his second, John Richardson, Franklin set to work planning.

First time in the field, as Canadian scholar Richard Davis has noted, Franklin relied for success on a diversity of peoples: the native peoples of Yellowknife, French-Canadian and Métis voyageurs, Scottish fur traders, Inuit interpreters. None of these were accustomed to naval hierarchy, and to blindly following orders. Second time out, he intended to rely mainly on men who would never question his directives. And he would have these Royal Navy seamen sent out early.

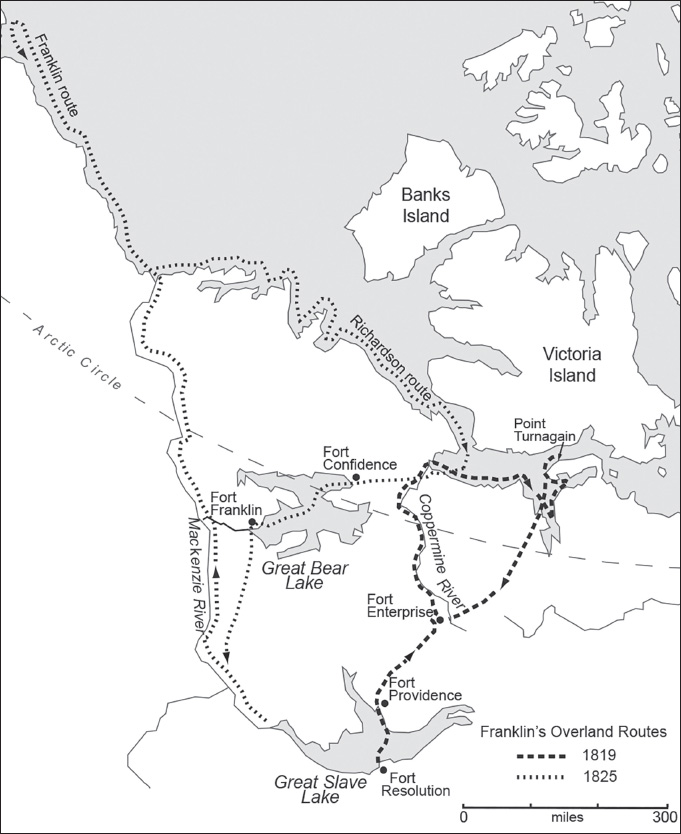

Franklin proposed to complete the mapping of the North American coastline to the west of the Coppermine River. He and John Richardson would cross the continent and then descend the Mackenzie River to the coast. From there, Richardson would travel east to the Coppermine, while he himself would explore westward to Icy Cape, which Captain James Cook had reached from the Pacific in 1778.

This expedition would constitute a rebuttal to Russia’s expansionary claims in the Arctic. In his detailed proposal to the Admiralty, Franklin also outlined scientific objectives. Having kept abreast of research by Michael Faraday and others, he proposed to take magnetic observations to locate the north magnetic pole and help determine whether the aurora borealis was an electromagnetic phenomenon.

The Admiralty approved. On February 16, 1825, accompanied by Richardson, John Franklin sailed out of Liverpool for New York City. From there, the two men travelled north by coach through Albany and Rochester, then crossed the Niagara River to Queenston Heights. Franklin admired the lofty monument to Sir Isaac Brock, who had died there in 1812, and who, like himself, had been present in 1801 at the Battle of Copenhagen.

Franklin’s overland expeditions are usually dated according to their departures from England in 1819 and 1825.

Franklin sailed by schooner to York, which would eventually become the metropolis of Toronto, but was then a town of 1,600 that failed to engage him. The designated voyageurs had yet to arrive from Montreal and, after waiting a few days, Franklin proceeded north 150 kilometres to Penetanguishene on Georgian Bay, a naval base built to protect British interests on the Great Lakes. Here, experts had readied two of the largest canoes used in the fur trade—“Montreal canoes” or canots de maître. These were roughly eleven metres long and almost two metres wide, and could carry three tons of cargo (sixty-five of the usual ninety-pound packs).

The voyageurs from Montreal caught up with Franklin on April 22, 1825. They gave him a letter that said his talented young wife, born Eleanor Porden, had died of tuberculosis mere days after he sailed out of Liverpool. “Though I was in some measure prepared for this melancholy event,” he wrote later, he had “fondly cherished the hope that her life might have been spared till my return.” Grief “rendered me little fit to proceed” with organizing the next day’s departure. Not wanting to slow the expedition, Franklin left final preparations to Back and Richardson.

Next day, the expedition set out westward. At this point, it comprised thirty-three men: four British officers, four marines, a naturalist and two dozen voyageurs. The party reached Fort William on May 10, and there traded the two big canoes for four smaller (twenty-five-foot) canots du nord. Leaving George Back to bring forward three heavy-laden craft, Franklin and Richardson went ahead with a light load. They followed the old fur-trade route through Lake Winnipeg, then up the Saskatchewan River to Cumberland House.

Arriving in mid-June, they learned that an advance party sent out the previous year through Hudson Bay had wintered here and left thirteen days before. It included boatmen and carpenters with three sturdy boats, as well as two Inuit interpreters from Fort Churchill, Tattannoeuck and Ouligbuck. Franklin and Richardson ascended the Churchill or English River and overtook that slow-moving brigade on June 29. After traversing the nineteen-kilometre Methye Portage, the two officers pushed northward to Fort Chipewyan on Lake Athabasca.

Here, Franklin sent Richardson ahead to Great Slave Lake, in present-day Northwest Territories. On July 23, George Back arrived with the three canoes. With most of the continent crossed, and the heavy lifting done for now, Franklin discharged a number of men. He joined Richardson at Fort Resolution, where he met two guides from his previous expedition, Keskarrah and Humpy, brothers to Akaitcho. They confirmed that many of the Yellowknife hunters who had saved his life during his first expedition had since been killed by a group of Dogrib people.

The expedition proceeded 550 kilometres farther north down the Mackenzie River to Fort Simpson. Here Franklin met up with two voyageur-guides sent by Peter Warren Dease, a Hudson’s Bay Company officer appointed to assist him. On August 5, the party continued still farther north to Fort Norman, and there split into three groups. George Back went up the Great Bear River to where Dease was building Fort Franklin. Richardson followed, but travelled beyond that site to scout Great Bear Lake for a route of eventual return from the Coppermine River.

Franklin continued north down the Mackenzie. He brought Tattannoeuck, whom he called “Augustus,” because he spoke better English than Ouligbuck. During this initial sortie down the Mackenzie, the expedition surprised a group of Dene, who immediately sprang to arms. Tattannoeuck calmed them and, according to Franklin, quickly became “the centre of attraction.” The Dene had recently made peace with local Inuit, and were excited to meet an Inuk from the faraway shores of Hudson Bay. Franklin and junior officer Edward Kendall donned their uniforms and distributed small gifts, but Tattannoeuck remained the star attraction.

“They all caressed and played around him with the greatest possible delight,” Franklin wrote, “and repeatedly expressed their joy at seeing him. My former high opinion of Augustus was even increased by the great propriety and modesty he evinced under these bursts of applause and favour. He treated them all with kindness and affability at the same time that he continued to perform his office of cooking, which he had undertaken to do for Mr. Kendall and myself on the journey. And when he sat down to breakfast, he gave to each of them a portion of his fare.”

Franklin reiterated: “We could not help admiring the demeanour of our excellent little companion under such unusual and extravagant marks of attention. He received every burst of applause . . . with modesty and affability, but would not allow them [the Dene] to interrupt him in the preparation of our breakfast, a task he always delighted to perform.”

Continuing north, the men saw many signs of Inuit habitation, but no people. On August 17, having emerged from the Mackenzie River delta into the salt waters of what is now the Beaufort Sea, Franklin named Garry Island, built a small cairn and left an account of his expedition so far. He also planted a silk Union Jack that had been embroidered by his late wife. Later he wrote, “I will not attempt to describe my emotions as it expanded to the breeze. However natural and, for the moment, irresistible, I felt that it was my duty to suppress them, and that I had no right by an indulgence of my own sorrow to cloud the animated countenances of my companions.”

Franklin turned then and headed back up the Mackenzie, with the men “tracking” or towing the boats against the current. The party reached their winter quarters on the evening of September 5. During the past couple of months, the veteran fur trader Peter Warren Dease had supervised construction of Fort Franklin, which comprised several buildings at an old fur-trading site on Great Bear Lake.

In his famous Character Book, governor George Simpson had assessed Dease in 1832: “Very steady in business, an excellent Indian Trader, speaks several of the Languages well and is a man of very correct conduct and character. Strong, vigorous and capable of going through a great deal of Severe Service but rather indolent, wanting in ambition to distinguish himself in any measure out of the usual course . . . His judgement is sound, his manners are more pleasing and easy than those of many of his colleagues, and altho’ not calculated to make a shining figure, may be considered a very respectable member of the concern.”

Approximately fifty people settled in for the winter, among them Dease, four naval officers, nineteen British sailors, nine voyageurs, the two Inuit, yet another interpreter, four hunters, ten women and a few children. Over the next few months, the officers taught classes and took meteorological and magnetic readings. The carpenters built a fourth boat, and the men hunted and fished and hauled firewood. Many of the sailors were Highland Scots, and one of them, a bagpiper named George Wilson, found his talents much in demand. The men also played ball hockey, danced and enjoyed occasional puppet shows mounted by George Back.

By June 22, after much preparation, all the men were out on the water except Dease, who happily stayed behind to maintain Fort Franklin. The men proceeded down the Mackenzie River to the coast, where on July 4, 1826, at Point Separation, Franklin divided the expedition. With the interpreter Ouligbuck and nine other men, Richardson and Kendall went east in two boats, the Dolphin and the Union. They had twenty-six bags of pemmican and enough food to last eighty days. They would proceed to the mouth of the Coppermine River, and return to Fort Franklin by ascending that waterway.

Franklin and George Back, with fourteen men, including Tattannoeuck, would follow the Arctic coast westward. They hoped to reach Icy Cape, pinpointed by James Cook, and there possibly meet a naval vessel coming from the Pacific under Frederick Beechey. If they succeeded, they would sail home on that ship. If not, they would reverse their outwards journey. For three days, Franklin and his men probed the island maze, seeking a westward channel.

Then, at the mouth of the Mackenzie River, came the great crisis of the expedition. July 7, 1826. Early afternoon. With fifteen men and two sturdy boats, the Lion and the Reliance, Franklin hit upon a westward channel. He was preparing to set out along the coast when one of his men spotted a “crowd of Esquimaux tents” on an island four kilometres distant. The sailors took out an assortment of gifts and covered everything else.

They proceeded slowly under sail. About two kilometres out, shallow waters forced a halt. The visitors beckoned to the Inuit to approach. Three canoes set out from the island, followed by seven more, and then an additional brigade of ten. Then came another brigade, and another, and Franklin found himself surrounded by 250 Siglit Inuit in seventy-eight canoes.

The older men in the first canoe, clearly the leaders, kept their distance until Tattannoeuck managed to assure them, as Franklin wrote, “of our friendly intention.” He explained that the visitors were “seeking a channel for ships”—the Northwest Passage—that would benefit the local people.

The Siglit Inuit, who would later be superseded in this area by Inuvialuit, expressed delight. In the shallow water, and with the tide at a low ebb, they crowded around. Franklin ordered the two boats seaward to escape the crush, but both ran aground in midstream. Several Inuit tried to help, but “we unluckily overturned one of the canoes with our oars.”

This was obviously a kayak, because the Inuk was “confined in his seat, and his head under water.” Franklin granted permission to haul him aboard. To warm the man, Tattannoeuck wrapped him in his own greatcoat. The welcome prompted other Inuit to try to come aboard. Two of the leaders communicated that if they were permitted to do so, they would keep the others away. Franklin allowed this.

George Back, his second-in-command, managed to get the second boat, the Reliance, afloat. He waited nearby. But now a number of Inuit were walking “in the water not up to their knees . . . and striving to get into the boats.” They proceeded to drag the two boats ashore, still smiling and expressing friendly intentions by tossing their knives and arrows into the Reliance. As soon as that first boat reached shore, however, forty men crowded around with knives in their hands. They began plundering the Reliance, and though badly outnumbered, Back and his men fought them for every article.

Meanwhile, as other Inuit dragged the Lion ashore, the two chiefs in the boat caught hold of Franklin’s wrists, one to each side, “and made me sit between them.” Three times Franklin struggled free, but “they were so strong as to reseat me and had I judged it proper to have fired I certainly could not have done it.”

Tattannoeuck “was most active on this trying occasion,” Franklin wrote. He jumped into the water “and rushing among [the Inuit] on the shore, endeavoured to stop their proceedings, till he was quite hoarse with speaking.” George Back got the Reliance afloat and ordered his crew “to present their guns.” This “so alarmed the Esquimaux that they ran off in an instant behind the canoes.”

Franklin then got the Lion afloat. The two boats reached deeper water, but soon ran aground again. A party of eight men approached and invited Tattannoeuck to speak with them. At first, Franklin refused to hear of this. But the interpreter “repeatedly urged that he might be permitted, as he also was desirous of reproving them for their conduct.” Franklin relented.

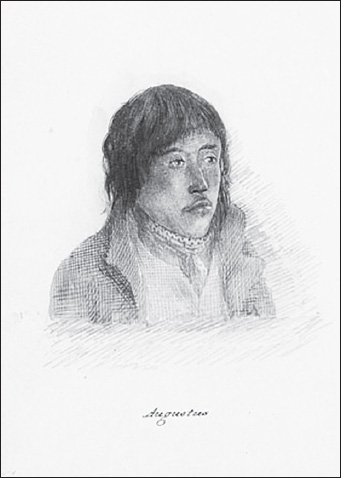

But for the courage of Tattannoeuck (Augustus), Franklin’s second overland expedition would almost certainly have ended in disaster. Robert Hood drew this portrait at Fort Enterprise.

Tattannoeuck “intrepidly went and a complete explanation took place.” He pointed out, Franklin writes, “that it was entirely forbearance on our part that many of them had not been certainly killed, as we were provided with the means of firing at a long distance. He told them that we were come here entirely for their benefit.” He said that he himself, well clothed and comfortable, was proof “of the advantages to be derived from an intercourse with the whites.” Tattannoeuck went on in this vein with more than forty people around him, Franklin wrote, “and all of them with knives, and he quite unarmed. A greater instance of courage has not been I think recorded.”

The Siglit said they were sorry, that they had never before seen white men, and that everything looked so new and desirable “that they could not resist the temptation.” They promised that they would never repeat this reception. When Tattannoeuck relayed this information, Franklin asked him to test their sincerity by demanding the restoration of a kettle and a tent. This he did and soon got them back.

Tattannoeuck remained on shore with the Siglit Inuit and sang with them, delighting them “as they found the words he used to be exactly those used by themselves on occasions of a friendly interview.” The tide began to rise at midnight, with the sun still visible in the sky. Around 1:30 a.m., Franklin and his men were able to set off rowing.

Without Tattannoeuck, these events at “Pillage Point”—the worst crisis of Franklin’s second expedition—would certainly have ended differently. Franklin and his men might well have shot dead a couple of dozen Inuit before they themselves were overpowered and killed. Imagine the repercussions, the way Britain would have reacted, and give thanks for Tattannoeuck.

Franklin and his men proceeded westward. Over the next few weeks, battling gales, fog, blizzards and lingering ice, they made slow progress. The expedition met several groups of friendly Inuit, some of whom expressed surprise that they had brought no sleds or dogs so they could travel over the ice. On July 31, the expedition reached “Demarcation Point,” which then marked the boundary between Russian and British territories, and today indicates the border between Alaska and Yukon.

The first two weeks of August brought more ice, fog and stiff breezes. With rare exceptions, the men could travel westward only ten or eleven kilometres a day. Finally, on August 16, at a place he called Return Reef, Franklin acknowledged that he would not be able to reach Icy Cape. He was just shy of 149° west longitude. From the mouth of the Mackenzie, he had travelled little more than halfway to Icy Cape. Later he would learn that a boat sent from Beechey’s ship had reached within 260 kilometres of Return Reef.

A brief sunny spell allowed Franklin to extend his survey twenty-four kilometres more to Beechey Point, but on August 18, he started back towards the Mackenzie. During the ensuing journey, more than once, friendly Inuit told Tattannoeuck that some of the hunters who had assaulted the expedition at Pillage Point intended to attack again, and this time to take what they wanted. They would do so under the guise of seeking to return stolen kettles. Franklin and his men kept a close watch, but did not again encounter the aggressive Siglit.

On September 21, after a tough slog up the Mackenzie, the expedition reached Fort Franklin. The party had added 630 kilometres to the coastal map. John Richardson had already returned and, as a naturalist, departed to do more scientific research. His eastern detachment, having travelled 2,750 kilometres in seventy-one days, had mapped 1,390 kilometres along the coast between the Mackenzie and the Coppermine. With their Mackenzie River journeying, Franklin and his men had travelled farther, a total of 3,295 kilometres. But they had charted less. The expedition as a whole had mapped 2,018 kilometres of coastline.

Canadian scholar Richard Davis writes that “Franklin’s contribution as leader of the main expedition . . . should not be eclipsed by Richardson’s greater success.” That accords with hierarchical Royal Navy conventions, certainly, which bestow all accomplishments on the nominal leader of any enterprise. But with Richardson (and Ouligbuck) having charted almost 70 percent of the total, some readers may wonder why Franklin should get all the credit.

John Franklin left winter quarters in late February 1827. He travelled mostly overland to Great Slave Lake and then to Fort Chipewyan, on Lake Athabasca, where he watched the arrival of spring. On May 26, the annual fur-trade brigade departed for York Factory. A few days later, Franklin set out for Cumberland House, where, for the first time in eleven months, he met up with Richardson.

The two men agreed that they had virtually completed the discovery of the Northwest Passage—although how, exactly, is hard to say. The southern channel they had begun mapping lacked a south-north link to Barrow Strait and Lancaster Sound. Yet, writing to his wife, Richardson articulated the first of several specious claims he would advance: “The search has extended over three centuries, but now that it may be considered as accomplished, the discovery will, I suppose, be committed, like Juliet, to the tomb of all the Capulets, unless something more powerful than steam can render it available for the purpose of mercantile gain.”

At Norway House, Franklin and Richardson said goodbye to Tattannoeuck, who reportedly grew teary-eyed at the separation. He swore that the two naval officers could count on him, should they ever need him again. The two naval officers carried on to Lachine, near Montreal, and settled accounts with the Hudson’s Bay Company. They proceeded south to New York City and, on September 1, 1827, sailed for home in a packet ship.

Tattannoeuck made his way from Norway House to Fort Churchill, where he spent three years working as a hunter and interpreter. He then did the same at Fort Chimo, in what is now northern Quebec. In 1833, he heard that George Back was organizing an expedition to search for John and James Clark Ross, who had disappeared into Prince Regent Inlet on a private expedition. Having enjoyed working with Back during the two Franklin expeditions, Tattannoeuck hurried to Fort Churchill, bought supplies—a pound of gunpowder, two pounds of ball shot, one-half pound of tobacco—and set out on foot to join the naval officer at Fort Resolution.

After travelling for weeks, he reached that location and learned that Back had moved 320 kilometres northeast to Fort Reliance. Tattannoeuck set out to join him there but got lost when a storm came on. He tried to retrace his steps but died at Rivière-à-Jean, just 32 kilometres from Fort Resolution. On hearing what had happened, a saddened George Back wrote: “Such was the miserable end of poor Augustus!—a faithful, disinterested, kind-hearted creature, who had won the regard not of myself only, but I may add of Sir John Franklin and Dr. Richardson also, by qualities, which, wherever found, in the lowest as in the highest forms of social life, are the ornament and charm of humanity.”

To that, a contemporary reader might add that George Back was forgetting the best reason of all to remember Tattannoeuck. At the mouth of the Mackenzie River, in July 1826, that brave and modest Inuk saved John Franklin and his second overland expedition from almost certain destruction. Tattannoeuck saved the life of Franklin, which meant that, two decades later, that naval officer was still alive when the British Admiralty began casting about for someone to lead yet another expedition to solve the riddle of the Northwest Passage.