PROLOGUE

Challenging “Official” History

The discoveries of Erebus and Terror have sparked renewed interest in the history of Arctic exploration, and particularly in the long-lost expedition of Sir John Franklin. Even before archaeologists finished searching the ships, analysts went to work parsing the implications of the findings. Did early searchers misinterpret the one-page record found on the northwest coast of King William Island, where in 1848 Franklin’s men landed after abandoning their ice-locked vessels? Did some sailors return and reboard? Did they drift south, or did they actively sail one or both ships? Does it matter? “Franklinistas” yearn for answers to such questions.

On the other hand, some thinkers have suggested that this single-minded focus, the “gravitational pull of the Franklin disaster,” distorts our understanding of exploration history. In Writing Arctic Disaster, Adriana Craciun argues that Franklin made only a minor contribution to Arctic discovery. And she questions the wisdom of celebrating “a failed British expedition, whose architects sought to demonstrate the superiority of British science over Inuit knowledge.”

This book, Dead Reckoning: The Untold Story of the Northwest Passage, sets out to navigate between extreme positions. It is a voyage of discovery. The late Pierre Berton established a point of departure, a known past position, with The Arctic Grail. But that work appeared in 1988—almost three decades ago. To determine our present position in these agitated seas, we must take into account everything we have learned since then—about climate change, for example, and the Inuit oral tradition. Berton begins his history in 1818, with a Royal Navy initiative, so signalling his acceptance of the orthodox British framing of the narrative. Since The Arctic Grail appeared, numerous Canadian authors have drawn attention to Inuit contributors. But until now, nobody has sought to integrate those figures into a sweeping chronicle of northern exploration.

To research Dead Reckoning: The Untold Story of the Northwest Passage, I have visited Scotland, England, Tasmania, Norway and the United States. In the Arctic, I have had the privilege of going out on the land with Inuk historian Louie Kamookak. And every summer since 2007, I have sailed in the Northwest Passage as a resource staffer with the travel company Adventure Canada. On board ship, when I wasn’t giving talks, I learned from such Inuit culturalists as politician Tagak Curley, lawyer-activist Aaju Peter and singer-songwriter Susan Aglukark. I rubbed shoulders also with archaeologists, geologists, ornithologists, anthropologists, art historians and wildlife biologists. My voyaging immersed me in debates over climate change, adventure tourism and who controls the Northwest Passage.

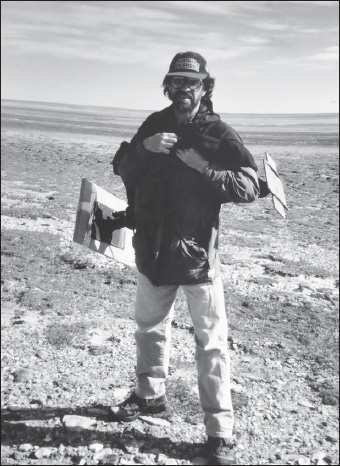

Along the way, I revelled above all in visiting historical sites. On one occasion, we chanced upon an impressive cairn in a bay off Boothia Peninsula, and I determined only later that it marked the grave of a cook who had sailed with Canadian explorer Henry Larsen. On another, we explored Rensselaer Bay on the Greenland coast, where Elisha Kent Kane spent two winters trapped in the ice. Back in 1999, years before these outings, I had gone north to locate a cairn that explorer John Rae had built in 1854 and, with a couple of friends, ended up lugging an awkward plaque across bog and tundra.

The author in 1999, lugging a plaque to the John Rae cairn overlooking Rae Strait.

The Clipper Adventurer, now called the Sea Adventurer, is an expeditionary cruise ship that sails frequently in the Northwest Passage.

That experience stayed with me. But I also vividly remember my initial Adventure Canada visit to Beechey Island, where in 1846 John Franklin buried the first three men to die on his final expedition. After going ashore in a Zodiac, we stood gazing at their graves while a bagpiper played “Amazing Grace” and giant flakes of snow softly fell and melted as they hit the ground. I felt moved by what I heard and saw—the skirling of the pipes, the desolate loneliness of the landscape. And yet, even after reading the wooden headboards, facsimiles of the originals, I felt more shaken by what I did not see—by the absence of ice.

At this time I was writing Race to the Polar Sea, and I knew we had arrived at Beechey Island two weeks later than Kane had in 1850. And yet, where his ship got frozen into pack ice, and he struggled through snow and ice when he stumbled ashore, I saw nothing around me but open water and naked rock and scree. As I stood at the three Franklin graves, I realized that climate change is bringing a centuries-old saga to an abrupt conclusion. And that nineteenth-century stories of Arctic exploration are more relevant than ever—irreplaceable touchstones that enable us to compare and contrast, and to grasp what the Northwest Passage is telling us.

In style and structure, Dead Reckoning is more literary than academic, more narrative than analytical—although, yes, I am bent on dragging Arctic discovery into the twenty-first century. By the time I set foot on Beechey, I had spent most of a decade researching and writing about northern exploration. Yet I was still meeting people who believed that John Franklin was “the discoverer of the Northwest Passage.” In the twentieth century, even some Canadian historians followed their British counterparts in creating an “official” history that culminates not with the triumphant Northwest Passage voyage of Amundsen, nor with the discovery of Rae Strait, which enabled the Norwegian explorer to succeed, but with Franklin’s calamitous 1845 expedition.

Orthodox history nods grudgingly towards those non-British voyagers who cannot be completely ignored—men like Amundsen, Kane and Charles Francis Hall. Yet it continually shortchanges those highlighted by another book from the mid-1980s—Company of Adventurers by Peter C. Newman. Fur-trade explorers who made remarkable contributions by working with native peoples include Samuel Hearne, Alexander Mackenzie and John Rae, the first great champion of Inuit oral history. A peerless explorer, Rae was defrauded of his rightful recognition after a campaign led by Lady Franklin, widow of Sir John. Ironically, she too looms large in these pages because she orchestrated an Arctic search that transformed the map of Canada’s northern archipelago.

The Beechey Island gravesite. The three farthest headstones, which are replicas, mark the graves of the first crewmen to die (in 1846) during the last expedition led by John Franklin. The nearest grave is that of Thomas Morgan of HMS Investigator, who died here in 1854.

The twenty-first century demands a more inclusive narrative of Arctic exploration—one that accommodates both neglected explorers and forgotten First Peoples. With Dead Reckoning: The Untold Story of the Northwest Passage, I hope to restore the unsung heroes to their rightful eminence. Certainly, such British naval officers as Franklin, James Clark Ross and William Edward Parry risked starvation, hardship and often their very lives in a quest for glory at the top of the world. But they were far from alone. Dead Reckoning recognizes the contributions of the fur-trade explorers, and of the Dene, the Ojibway, the Cree and, above all, the Inuit, whose Thule ancestors have inhabited the Canadian Arctic for almost one thousand years. Were it not for the Inuit, John Franklin’s ships would still be lying undiscovered at the bottom of the Arctic Ocean.