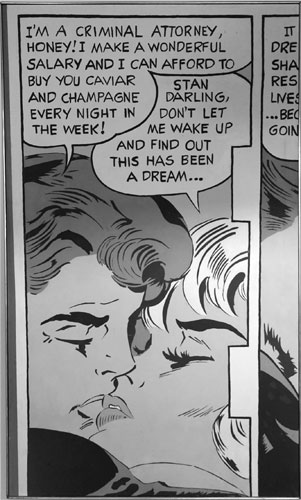

WHEN I WAS GROWING up, our living room was dominated by a six-foot-high picture of a comic-strip panel in the style of Roy Lichtenstein. The painting depicts a man and a woman kissing in tight close-up, dialogue bubbles floating above their heads. The man says, “I’m a criminal attorney, honey! I make a fabulous salary and can afford to buy you champagne and caviar every night of the week!”

The woman replies, “Stan, Darling, don’t let me wake up and find out this has been a dream . . .”

That scenario drew from life: my father was indeed a criminal defense attorney named Stanley, my mother blonde, just like the woman in the picture. She had commissioned the painting for his birthday from a client of his, an artist who had gotten busted for drugs. But visitors to the house didn’t know that last bit of information. They would look at the painting and say, “Hey, isn’t that by what’s-his-name?”

“Roy Lichtenstein?”

“Yeah, that guy in the museums.”

We would smile with great modesty, letting the mistake vibrate around us, uncorrected.

In quiet moments, with nobody around, I would sit on the couch and stare at the painting, trying to figure out what it said about us. Mom and Dad were characters in a piece of art, real but more than real, so fabulous that they could spoof themselves in a fake Lichtenstein and be even more fabulous for it. Except we didn’t tell anyone that it was a fake. Neither did we claim that it was real. The painting was a little like what my father did in court, spinning stories for the jury that were beautiful possibilities, wishes that lived in the spaces between the facts. And yet the painting had truth inside it, too—I could feel it there, in the man and the woman, the kiss. I would try to make sense of the dialogue bubble in the next panel, only a sliver of which was visible, reading it as if it were a crossword that needed to be filled in: It, dre, sha, res, lives, bec, goin . . . It isn’t a dream, my love. We shall live the rest of our lives together, because we are going to be happy.