Chapter Two

Male and Female

The very first British tank went into service in 1916, exactly two years after the outbreak of the First World War. Its rather peculiar and very distinctive rhomboid shape was to ensure a long track run capable of crossing the vast trench networks on the Western Front. The tracks ran around the outer edges of the entire hull and could manage a very modest 3.7mph. Speed was not really an issue as the tank was intended to match the pace of the infantry. The resulting height of the hull meant a turret would have made the vehicle top heavy, so the main armament was placed in sponsons on either side. It was dubbed rather unimaginatively the Mark I of which just 150 were built in two types.

The male, weighing in at 31 tons, was armed with two 6-pounder naval guns mounted in side sponsons and four Hotchkiss machine guns in ball mounts. The female weighed only slightly less at 30 tons and was armed with six machine guns. The idea was that the males could deal with enemy defences, fortifications and guns while the females went after enemy troops.

The Mark I male was easily distinguishable from other marks of British heavy tank because of the length of its gun barrels. The 6-pounders were the original Admiralty pattern 8cwt 40 calibre, but these were replaced in the Mark IV onwards with the shorter 6 cwt 23 calibre gun the barrel of which was less likely to get stuck in the mud or damaged by buildings and trees. It could traverse 100º from dead ahead and had a muzzle velocity of 554m/sec compared to 441m/sec for the 23-calibre gun. Ammunition carried consisted of High Explosive (HE), Armour Piercing (AP) and case shot (anti-personnel for use against infantry in the open) and totalled up to 332 rounds. The initial naval guns had a far greater range than was really necessary for the tank’s role.

The Mark I (and subsequent marks) featured a raised cupola in the hull front for the driver and the commander, who also served as brakesman. External features peculiar to the Mark I included the protective bomb roof and wheeled steering tail. The former comprised a wood or metal frame covered in chicken wire mounted on the hull roof to deflect grenades. This subsequently proved unnecessary and was discarded. The steering tail was introduced on the prototypes to help with steering and stability. It comprised two iron-spoked wheels fitted to an Ackerman steering axle, which was controlled from a steering wheel in the driver’s position by wires. The idea was the rudder action of the tail could accomplish minor coursecorrections or large-radius turns without resorting to a gear-change on the tracks. This steering unit could be raised from the ground for transport.

The engine, a Daimler 105hp petrol type, was mounted in the centre of the hull. This was served by a two-speed gearbox with a differential drive to the two cross shafts at the front and back. These were joined to the four ‘horns’ of the tank, in particular to the rear drive sprockets by chain drive and reduction gear. A tubular water radiator was installed behind the engine with the fan driven by the engine. The exhausts were fitted to holes in the roof. In an effort to dissipate sparks and smoke twin baffle plates were installed.

The designers were rightly proud of themselves and there is no denying that the Mark I looked a formidable beast. It could cross enemy trenches up to 11ft wide and tackle obstacles up to 4ft tall. However, they were not given sufficient time to iron out the inevitable teething problems or indeed fine-tune the overall design. The necessities of war ensured that the very first British tank, like so many that were to follow it, was rushed into combat before it was really ready.

The weight of the tank placed a tremendous strain on the drive train, which resulted in it being mechanically unreliable. Notably, climbing up steep inclines caused fuel starvation due to the gravity fuel feed system. The fuel also presented the risk of fire especially as the petrol tanks were mounted high in the hull. The gun sponsons could be unbolted for transportation in order to reduce the weight and width, but as each weighed 1 ton 15cwt this was no easy task. Access was not easy either. There was a manhole opening in the roof, but normally the crew clambered in and out of the vehicle via the doors in the rear of the sponsons. The steering tail while useful on good ground could not cope with the realities of No Man’s Land. Following the Mark I’s debut on the Somme it was decided to discard the tails in November 1916, steering solely by gear-changes.

In addition, the fighting compartment for the eight-man crew was a hellish place to be. Many of the new crews had in fact not seen action on the Western Front, so were not sure what to expect and they were drawn from all branches of the army. For a start it was impossible for them to stand upright and after half an hour running the massive engine the temperature could reach well over 100°F. To counter this crews gulped down up to a gallon of water per man per day. Although fume outlet louvres were cut into the rear of the vehicle, fresh air for the engine had to be drawn in from the crew openings in the hull. Noxious fumes from the engine soon filled the interior and made the crews delirious and nauseous. As with all tankers down through the ages if they wanted to urinate during combat they had to resort to a spent shell case.

Not only was the ventilation poor, so was the visibility. The vision devices were crude, consisting of just slits or flaps. The ride was rough as the tracks were not sprung. The armour posed a danger to the crew as the plates were riveted to unarmoured girders and angle irons. This meant that when the joins were hit even by small-arms fire the crew with be subject to ‘splash’ or spalling by the rivets and armour.

Noise from the petrol engine was such that verbal communication was impossible. The driver had to relay his orders to the two gearsmen by hammering a set code on the engine cover. Gunner A. H. R. Reiffer, MM who fought in a Mark I at Flers recalled, ‘There was hell outside all right, but there was such a hell of a noise inside and we were such a tight-packed crew, that we didn’t concern ourselves with what was happening outside.’

The tank had to be steered either by putting one track into neutral and the other into first or second gear, or by applying the brake on one side. Both had their disadvantages. Using the gears caused the tank to lurch round violently, while using the brake was exhausting for the brakesman and rapidly wore out the brakes. Using the clutch method of steering required four crewmen, the driver, brakesman and the two gearsmen. Separate gear operators were required for each track. Once the tank had turned, to ensure straight running another gear switch was required. Doing all this while under fire and in boggy conditions made the whole procedure even more difficult.

Production was slow and it was not until July 1916 that the first tanks left the factories. The following month just fifty were shipped to France. Under great secrecy crews had to be recruited and trained to man the Mark I. To try and hide what was going on this new organization was initially called the Armoured Car Section, Motor Machine Gun Service, then renamed for greater secrecy the Heavy Section, Machine Gun Corps. In light of the tanks being equipped with machine guns this did not seem too unreasonable. The ‘Heavies’ comprised 184 officers and 1,600 men, and they and their tanks were divided into six companies of four sections, each section consisting of three male and three female tanks.

Initial crew training in Britain was conducted at the Bisley ranges in Surrey, but once they had their first tanks they moved to Thetford, Norfolk on the estate of Lord Iveagh. It was from here that the first three companies departed for France in the summer of 1916. Toward the end of the year Bovington Camp, at Wool in Dorset, was selected as the new home of Britain’s very first tank force. The Mark I was blooded at the Battle of Flers-Courcelette, part of the renewed Somme offensive, on 15 September 1916.

British heavy tank designations ran from the Mark I through to the Mark X, though the VI, VII and X never came to fruition. The improved Mark II/III consisted of half-male and half-female variants. These were only intended as training tanks, but the Mark IIs ended up being shipped to France.

The key variant was the Mark IV, which was an up-armoured version of the Mark I, of which 1,220 were built comprising 420 males, 595 females and 205 tank tenders. This tank weighed 28.4 tonnes and required an eight-man crew. The male was armed with two 6-pounder guns plus three .303 Lewis machine guns, while the female was equipped with five Lewis guns. On the Mark IV and V females the sponsons were smaller being only half height top down. As with most British tanks of the time it was slow, managing just 4mph depending on the conditions. During the summer of 1917 the Mark IV fought at Messines Ridge and the Third Battle of Ypres. In November of that year 432 Mark IVs were committed to the Battle of Cambrai.

The smaller British Medium Mark A Whippet was designed to support the slow heavy tanks by exploiting any breakthroughs. The first production tanks were delivered in October 1917 from an order for 200; this was increased to 385 but later cancelled. The Whippet was directly derived from the experimental ‘Little Willie’ prototype. While the Whippet looks more like the tank as we know it, the crew compartment consisted of a fixed turret at the rear of the vehicle. This was armed with four machine guns, but as there were only three crew it meant that the gunner had his work cut out for him.

Efforts to improve the engine and transmission on British tanks resulted in the improved Mark V heavy tank. A number of Mark Is and IVs were fitted with various experimental transmissions, power units and clutches in February 1917 and tested by the Tank Supply Department in early March. Notably one was fitted with a epicycle gearbox that had been designed by Major Wilson. Epicycle gearing and brakes were used to replace the existing change speed gearing in the rear horns. Likewise a four-speed gearbox on the planetary principle replaced the two-speed box and worm gear. Another tank utilised the Westinghouse petrol-electric drive that was managed by one man. Also each track was given smoother variable speed control with the installation of a separate motor and generator. Another had a Daimler petrol-electric drive, while a third was fitted with Williams-Janney hydraulic pumps which gave a similar result.

The petrol-electrics had their advantages but were difficult to manufacture so it was decided to go with Wilson’s epicyclic gearbox. This meant that gear changes could be conducted by the driver – providing much better handling and control. While the resulting Mark V had a hull and armament similar to the Mark IV it featured a new purpose-built Ricardo tank engine with 150hp. The Mark V also had improvements to the hull. These included a raised cupola at the rear for the commander, which gave better visibility and access to the unditching beam. Extra protection was provided by a machine gun in the rear of the hull and for signalling a semaphore arm could be erected aft of the cupola.

This improved tank went into production in December 1917 at the Metropolitan Carriage and Wagon Works, Birmingham. The Tank Corps received the very first Mark Vs in France in May 1918. Although the Mark V began to replace the Mark IV by mid-1918 many Mark IVs remained in service when the war came to a close. In total some 400 of the Mark V were built with 50:50 male to female and these first saw combat on 4 July 1918 at the Battle of Hamel.

By late 1917 it was apparent that the trench-crossing capabilities of British tanks needed to be improved. This resulted in the Tadpole Tail, which was a kit that could stretch the rear horns of a tank by nine feet. Trails showed this to be unsatisfactory. The Tank Corps Central Workshop instead came up with a field modification, by adding an extra 6ft side panelling, that extended the tank hull rather than stretching the horns. This was designated the Mark V* and it was hoped to use it as a troop carrier – this variant was tried at Amiens but the fumes gassed the occupants. As a result it was used to carry stores, by the time of the Armistice 327 had been converted and were in service with the British Army and another twenty-three were deployed with the US 301st Tank Battalion along with twelve standard Mark Vs. A factory-built variant known as the Mark V** was not available until after the war ended.

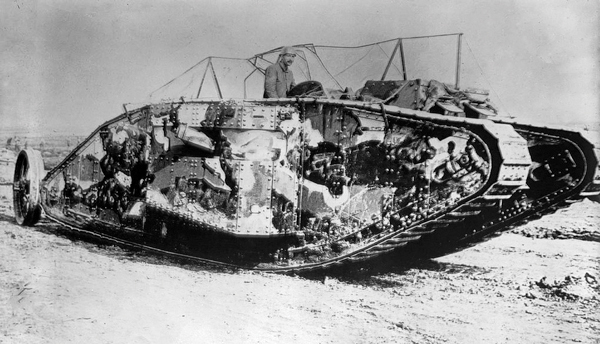

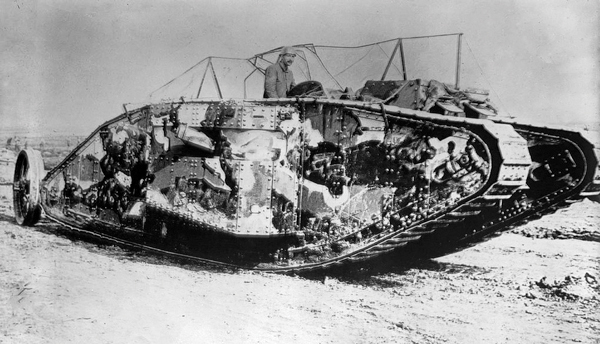

Mark I tanks were produced as male versions with 6-pounder guns mounted in their side sponsons and female versions armed with machine guns clad in armoured jackets or sleeves – seen here. This particular tank has been painted in the early Solomon camouflage scheme; its use was soon abandoned after mud made it completely unnecessary.

A British Mark I/II male tank dubbed Lusitania, identifiable by its long-barrelled naval 6-pounder (8 cwt 40 calibre) gun.

Access to the Mark I and subsequent models was primarily via the doors in the rear of the gun sponsons. This Mark II is fitted with the wide spudded track shoes, which clearly did not prevent it becoming stuck.

This Mark II male was photographed passing through a French village in 1917. It has baffle plates over its exhaust outlets.

Tank production was slow and the first fifty were not shipped to France until August 1916. These are Mark Vs being assembled by the Metropolitan Carriage and Wagon Company in Birmingham.

A field full of female tanks awaiting delivery.

Tanks in their storage sheds – vehicle training took place at Thetford in Norfolk.

British Vickers machine gun crew – initially the tank force was dubbed the Heavy Section Machine Gun Corps in part to keep its brand-new role secret. The Machine Gun Corps did not keep control of the tanks, the Tank Corps being created instead.

A Mark II male with spudded tracks captured by the Germans near Arras on 11 April 1917. This type of tank was only intended as a training vehicle but ended up being shipped to the front.

The subsequent Mark IV and V were armed with the shorter 6 cwt 23 calibre gun.

Mark IV male tank called Hyacinth temporarily stranded in captured German defences near Ribecourt in November 1917 during the Cambrai offensive.

Mark IV female with unditching beam at Peronne during the German offensive in March 1918. Note the much smaller machine-gun sponson.

Mark IV Male with Tadpole Tail extension.

This Mark V* female tank is carrying a ‘Crib’ which replaced the brushwood fascines for trench crossing. It is traversing the Hindenburg Line in 1918 along with a mortar team.

Preserved Mark V female – this again gives a clear view of the foreshortened sponson.