Jubilant British troops hitch a ride – the morale of the British 3rd Army was understandably high in light of the massed tank fleet spearheading the attack at Cambrai on 20 November 1917.

At 0600 on 20 November 1917 the Tank Corps attack at Cambrai opened. Their commander Brigadier Sir Hugh Elles rode into battle in a Mark IV male called Hilda. The Mark IV was the first British tank to be used en masse and was the main type that fought at Cambrai. Apart from problems experienced by the 51st Highland Division everything went pretty much to plan. Heralded by their roaring engines and great billowing clouds of petrol fumes the massed ranks of 470 tanks crawled into No Man’s Land and through the chaos caused by the opening bombardment.

Along with the gun tanks and their supporting infantry came something equally new in the realms of armoured warfare, wire-pulling tanks, radio tanks and supply tanks ready to assist wherever they were needed. Despite the commitment of this huge tank force, the British Mark IVs were eventually to succumb to the Germans’ determined defence and heavy firepower.

A tank thwarted attempts by the 20th (Light) Division to cross the St Quentin Canal at Masnières after it fell through the bridge. At Flesquières the 51st Highlanders became separated from their tanks. Upon crossing Flesquières Ridge the exposed tanks, whose supporting infantry were lagging behind, were met by well-trained and determined German gunners. This hold up left the divisions on the flanks exposed to enemy fire. The delay was attributed to the German Field Artillery Regiment 108 and General Harper’s reluctance to commit his reserves. The 51st Highlanders lost twenty-eight of their tanks, though not all of these were to German artillery. One of the effects the German fire had was to cause the tanks to lurch and veer all over the place. The result was that many became bogged down and had to be abandoned by their crews.

The 6th Division captured Ribécourt and Marçoing in the centre but the cavalry were late and subsequently repulsed at Noyelles. West of Flesquières, the 62nd (2nd West Riding) Division forced their way through to Havrincourt and almost to the woods on Bourlon Ridge; while the 36th (Ulster) Division on the British left reached the Bapaume-Cambrai Road.

The attrition rate for the Tank Corps was severe. By the end of 20 November 179 tanks were reported out of action, with sixty-five destroyed, seventy-one broken down and forty-three ditched. This sacrifice had not been in vain, however. A breach 4,000 yards deep and six miles wide had been cut into the Germans defences at the cost of less than 4,000 casualties. In England the church bells rang out at the news of the victory. If the advance had been stopped at this stage and kept within Fuller’s original concept of a limited tank raid then it would have been a remarkable victory.

Supported by 100 tanks and 430 guns the British attacked the woods on Bourlon Ridge on 23 November but made little progress. Four days later the 62nd Division, aided by thirty tanks, renewed the attack. Once in control of the crest of the ridge the British dug in to endure a deluge of 16,000 German shells. At 0700 on 30 November 1917 the Germans launched a counter-offensive at Cambrai with the intention of retaking the Bourlon salient as well as attacking around Havrincourt. By the end of the Battle of Cambrai the British had suffered 44,000 causalities for very little territorial gain. Nonetheless British tank tactics had proved largely sound and shaken the Germans.

A German officer from General Headquarters briefing members of the Reichstag on the British use of tanks at Cambrai reported: ‘The enemy employed them in unexpectedly large numbers. Where, after a very thoroughgoing blanketing of our positions with smoke clouds, they made surprise assaults, the nerves of our fellows frequently could not stand the strain. In such cases, they broke through our forward lines, cleared the way for their infantry, appeared at our rear, produced local panics and broke up in confusion the arrangements for directing the battle.’

Despite armoured warfare still being in its infancy the generals demanded the initial breakthrough be followed up. Because the cavalry failed to exploit the situation it fell to the infantry and the remaining tanks to widen the breach. Perhaps predictably the Germans managed to block any further advances and the remaining British reserves were expended gaining ground measured in just yards. Frustratingly in places the British were even forced back beyond their original start line. However, the Tank Corps could not held responsible for these subsequent disasters. At Gouzeaucourt it gained fresh credit when a timely tank counter-attack halted the German advance. This proved that tanks could capture and hold ground when the need arose.

While Cambrai showed what the tank could achieve with the element of surprise, operating en masse and with adequate infantry and artillery support, the failure to exploit the initial breakthrough remained a vexed issue. Rather unfairly, Elles and Fuller were criticized for not holding back part of the Tank Corps as a reserve. This seemed to miss the point that a smaller attacking force would have achieved a smaller breakthrough, which any reserves would have struggled to capitalize on.

What the battle also clearly demonstrated was that while the Mark IV was a vast improvement on its predecessors, it was simply too slow and heavy to exploit any breakthrough. The cavalry were no longer up to such a task, so what was needed was a lighter and faster tank that could charge through a breach and into the enemy’s rear area. The French had already come to this conclusion with the development of the FT-17.

In London leading politicians were far from happy about the outcome of the Battle of Cambrai. ‘This action was grossly bungled’, said Prime Minister Lloyd George, ‘and the tank success was thrown away through the ineptitude of the High Command’. In his memoirs Lloyd George was more specific, pointing the finger firmly at General Byng:

The first onset of the Tanks, on 20th November, was a brilliant success. Within a few hours the Hindenburg line was broken by these inexorable machines, and a penetration effected in the enemy lines as deep as that which had been achieved after months of terrible fighting and colossal losses on the Somme and at Passchendaele. It is generally acknowledged now that the advance was badly muddled by General Byng and that he could, even with the resources at his command, have made a better job of it. But what converted victory into defeat was a total lack of reserves.

This was grossly unfair. General Byng had little choice but renew his attack at Cambrai with just 130 tanks. The Tank Corps were not given enough time to recover the 114 tanks that had broken down or become stuck. These might have made a difference. Lloyd George was right about the lack of reserves and Haig was well aware of this. Elles and Fuller had set their sights on achievable goals for the Tank Corps, Haig and Byng had not and it was they who had not met Lloyd George’s expectations.

It was not an altogether auspicious start to massed mechanized warfare. The Germans, however, finally began to take note of the possibilities offered by the tank. Ironically, while the Mark IV became the most numerically significant tank of the war, it also became the most numerous German tank. The Germans gathered up all the Mark IVs they captured at Cambrai and the earlier actions at Charleroi and refurbished them. In German service the Mark IV was dubbed the Beute Panzerwagen IV or ‘captured armoured vehicle 4’. In December 1917 the German Army formed four tank companies employing around forty captured Mark IVs. However, the first tank-to-tank battle did not occur until April 1918, when cumbersome German-built A7Vs took on British Mark IVs at the Second Battle of Villers-Bretonneux. This heralded the true birth of tank warfare.

Jubilant British troops hitch a ride – the morale of the British 3rd Army was understandably high in light of the massed tank fleet spearheading the attack at Cambrai on 20 November 1917.

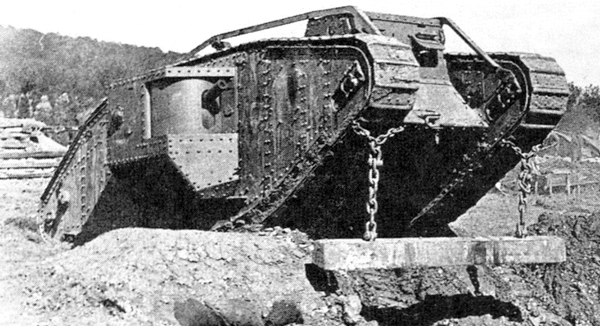

Mark IV male with unditching beam deployed for crossing enemy trenches. In total 432 Mark IVs were committed at Cambrai.

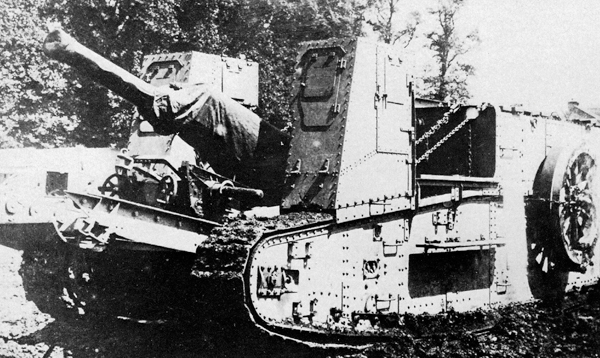

A British Mark I gun carrier bearing a 60-pounder gun. The weapon’s wheels have been removed and chained to the sides. This carrier’s potential as offensive mobile artillery was never realised. Just fifty were built and they ended up being used as supply and recovery tanks.

A Wire Cutter (hence WC) Mark IV broken down at Cambrai being used as an observation post.

To counter British tanks the Germans used flamethrowers and artillery. Flamethrowers were used by stormtroopers as part of their assault weaponry. The Germans deployed two man-portable variants, the Kleinflammenwerfer (small flamethrower) known as the ‘Kleif’ and the Wechselapparat or ‘Wex’. A larger trench-based variant was also used known as the Grossflammenwerfer.

The shattered remains of a female tank – in total the Germans destroyed sixty-five tanks during the Tank Corps assault at Cambrai.

Medics collect casualties amidst a tank graveyard. At Flesquières German field guns were manhandled forward to fire directly at the exposed tanks as they came over the ridge.

A disabled Mark IV tank near Cambrai. Both tracks have come off.

German soldiers recovering a captured Mark IV. A total of seventy-one tanks broke down and another forty-three became stuck at Cambrai.

This female tank picked a fight with a tree in November 1917 and lost.

Remains of a female tank captured at Cambrai. The Tank Corps lost 179 tanks on 20 November 1917.

A re-badged female tank at Armentières. At the end of 1917 the German Army formed four tank companies using forty captured British Mark IVs.

German infantry supporting a captured British tank. The German High Command was slow to accept the tank and development of the German A7V Sturmpanzerwagen was slow.

German troops familiarize themselves with an enemy tank now under new ownership.